In response to:

Losing the Economic Race from the September 27, 1984 issue

To the Editors:

Which economy is Lester Thurow talking about? The clank of goods manufacture echoes as a leit-motiv throughout his September 27, 1984 analysis of the decline of America’s international competitiveness. But offstage is heard the hum of an economy turning away from the production of goods and toward the provision of services. And on this score the despondent can take heart: international trade in services returns a positive trade balance to the United States.

But Thurow never approaches services directly. Rather, by seeking an end to “preferential financing for nonindustrial investments (such as commercial office buildings)…,” Thurow attacks the sites where services for domestic and export use are generated. Moreover, some of those structures—the so called “intelligent buildings”—may be considered a form of the “technically advanced factories” that Thurow wishes to encourage, “factories” where the output is information rather than merchandise.

Export sales of services are not without their “competitiveness” problems either. The positive service trade surplus has declined 25 percent between 1981 and 1983. This is in part traceable to the overvalued dollar that overprices American services in foreign markets. Thus it is in the services realm rather than the manufacturing environment that Robert Lawrence’s assessment of long-range American competitiveness is likely more accurate.

Francis T. Ventre

Director, Virginia Polytechnic Institute

and State University, Blacksburg, Virginia

Lester Thurow replies:

Unfortunately our surplus in the balance of payments on services does not reflect what it seems to reflect. In balance of payments statistics, interest payments on previous investments are counted as services. And in America’s case our service surplus is almost entirely interest payments. As a result the surplus does not reflect the competitive strength of our services industries, but the balance of lending.

As Professor Ventre points out the service surplus is declining rapidly. It is declining because the US is having to borrow massive amounts of money to finance its $130 billion trade deficit. And at current rates of borrowing the US will shift from being a net creditor country (owed more than we owe) to being a net debtor country (owing more than we are owed) sometime in 1985. At this point the service sector will shift from having a surplus to having a deficit.

I wish that our service sector was really competitive on world markets but this is one of those cases where the data don’t mean what they seem to mean.

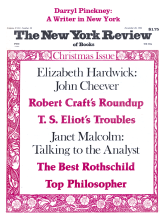

This Issue

December 20, 1984