In response to:

Happy Families from the June 14, 1984 issue

To the Editors:

I suspect that I am not alone among historians who have studied the family in being amazed at the choice of Geoffrey Elton to review Steven Ozment’s When Fathers Ruled: Family Life in Reformation Europe [NYR, June 14]. The views Professor Elton there expressed on family history are hardly unexpected, but they do cry out for comment.

The first of those comments must be the extraordinarily ahistorical attitude they reveal in an unquestionably eminent historian. Alice Clark remarked 65 years ago that “Mankind, lulled by its faith in the ‘eternal feminine’ has reposed in the belief that women remain the same, however completely their environment may alter, and having once named a place ‘the home’ thinks it makes no difference whether it consists of a workshop or a boudoir.”1 With the substitution of “family” for “home,” and without explicit recourse to the “eternal feminine,” Professor Elton has reproduced this view, commenting on “the family that emerged from the Reformation and could be seen predominant, in England as well as Germany and France, until at least a half-century ago,” [emphasis mine] assuring us that it was a Good Thing which satisfied most people.

Of course. One need not follow Lawrence Stone in believing that love was discovered by the upper middle class at the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth centuries, or Edward Shorter in finding the discovery of maternal affection in the middle class and sexual passion in the lower class at the end of the eighteenth century, in order to believe that the family has a history.2 It is, as Professor Elton suggests, improbable that most people lived their lives in a setting which made them miserable, but we must recognize that the conditions in which people were content at one time are not necessarily the same as those in which they are content at another. Furthermore, it is equally improbable that the family remained unchanged over four centuries during which (at the very least) its usual location changed from rural to urban, and its role changed from that of a center of production to a center of consumption. In acknowledging Ralph Josselin’s affection for his wife and children, we must also acknowledge that Josselin’s contemporaries were opposed to, but not at all surprised by, the desertion of wives by husbands, and by domestic violence.

In the unlikely event that historians took Professor Elton’s advice and “left [the family] in peace” our understanding of past society as a whole would suffer. As early seventeenth century writers on the family and household well understood, relations within the family were power relations and models for politics. The family, wrote William Gouge in 1618, was “a school wherein the first principles and grounds of government and subjection are learned…inferiours that cannot be subject in a family…will hardly be brought to yield such subjection as they ought in Church or Commonwealth.”3 Similarly, Matthew Griffith summarized the two principal duties of family members, that he intended to teach in his household manual: “They must fear God and the King and must not meddle with them that be seditious.” 4

The puritan clergy who wrote household manuals were not alone in these assumptions; they were shared by such non-puritans as King James I (who thought that the King became a father to his people at his coronation) and Sir Robert Filmer, who derived the absolute power of the King from the absolute power of a father over his children. John Locke took Filmer seriously enough to devote the entire First Treatise of Civil Government to the demolition of his theory. To say the family is a site of power relations does not mean that affection and happiness are absent, but that the way affection and concern is expressed within the family is shaped by conceptions of the nature and justification of authority in society at large. Thus it is not surprising that Edward Thompson found that in seventeenth century England, concerned as it was with the threat of rebellion, the shame brought by “rough music” was directed at couples where the wife dominated the husband; in the eighteenth century, with its focus on law and the limits on power, the object was increasingly the husband who beat his wife.5 As relations between governors and governed changed in state and society, so they changed in the family. Locke founded not only relations within the state on consent, but also those within the family.

To say that the family contains relations of power cannot, of course, reduce all political relations to the family or familial relations to politics. Instead it suggests that careful attention to the changing nature of relations within the family can help us understand the interpretations given to differing conceptions of authority. And it helps us to realize that changes in the family—its structure, organization, or ideals—do not mean its end. We all—even Professor Elton—see the history of the family (and indeed all history) with the eyes of the present. In recognizing the significance of the history of the family, we can be more understanding of its changing aspect.

Susan D. Amussen

Connecticut College

New London, Connecticut

G.R Elton replies:

It is good to know that, even though you (rightly) made me cut some of the nastier remarks from my review of Steven Ozment’s book, my intention to provoke proved successful. Historians of the family are quite right to rush to the defense of their subject. I congratulate Professor Amussen on her single-minded determination to find the source of all political theory in family relationships, but I must point out that I did know about Filmer’s patriarchalism and other metaphors derived from the fact that people have fathers whom as children they are instructed to obey. My critic’s sweeping conclusions drawn from these commonplaces do strike me as simplistic. Thus, so far as I know, the French family of the early twentieth century hardly reflected the effects of 1789—to take just one example. To understand relations between independent adults in terms derived from the relations between adults and children linked by blood is to elevate metaphor to the function of explanation, a method unfortunately much favored by social historians. As for change, it seems to me that even Professor Amussen’s own words do not convincingly demonstrate it. The contemporaries of Ralph Josselin, she says, “were opposed to, but not at all surprised by” certain marital misfortunes: does she suppose that today we approve of, or stand astonished at, the desertion of wives by husbands or domestic violence? Much evidence supports the view that the concept of the family as expounded by the writers of the Reformation era possessed a remarkably enduring character; personal observation suggests that in Europe at least it was, four hundred years after Luther, still unaltered in all essentials. Thus I remain doubtful about the proposition that changes in society can be successfully studied by an investigation of the history of the family.

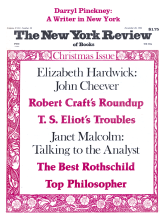

This Issue

December 20, 1984

-

1

Alice Clark, Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century (London, 1919, reprinted 1982), p.8.

↩ -

2

Lawrence Stone, The Family, Sex, and Marriage in England, 1500–1800, (New York, 1977); Edward Shorter, The Making of the Modern Family (New York, 1975).

↩ -

3

William Gouge, Of Domesticall Duties: Eight Treatises (third edition, London, 1634), p. 17.

↩ -

4

Matthew Griffith, Bethel: or, a forme for families (London, 1634), p. 429–430.

↩ -

5

E.P. Thompson, ” ‘Rough Music’: Le Charivari Anglais,” Annales: E.S.C. 27:2 (1972) pp. 285–312, and ” ‘Rough Music’ et Charivarl: Quelques réflexions complémentaires” in Le Charivari: actes de la table ronde organisée à Paris, 25–27 Avril 1977, ed. Jacques Le Goff and Jean-Claude Schmitt (Paris, 1981), pp. 273–283.

↩