(The following is drawn from “Tears, Blood and Cries: Human Rights in Afghanistan Since the Invasion, 1979–1984,” a Helsinki Watch report issued in December.)

“A whole nation is dying. People should know.” The terseness and directness of this statement befitted the speaker—Mohammad Eshaq, a resistance leader from Afghanistan’s Panjshir Valley, a man of strong convictions and determination. Yet his eyes were filled with tears when he told us about the fate of two men, brothers, from his ancestral village of Mata. Aged ninety and ninety-five, and blind, they stayed behind when the rest of the villagers fled during last spring’s offensive: “The Russians came, tied dynamite to their backs, and blew them up.” He paused to collect himself, then added simply: “They were very respected people.”

For five years now, in their remote, mountainous land in the center of Asia, the people of Afghanistan have been defending their independence, their culture, their existence itself, in a desperate battle with one of the world’s great super-powers. Yet the inherent drama of such a confrontation does not appear to have captured the world’s imagination. News from Afghanistan has been scarce.

There are many reasons for this. The Afghan government has officially closed its doors to most of the major world media and to international humanitarian organizations, and the information it releases is dictated by the needs of official propaganda. The Afghan resistance parties based in Pakistan, on the other hand, are hardly objective sources of information and are often at odds with one another as well. Independent investigation requires the visitor to enter the country illegally from Pakistan, trek for weeks over forbidding terrain, and brave the dangers of a war without fronts. The largest group of victims consists of uneducated people, immersed in their own traditions, with no idea of how to tell their story to a foreign world.

What little news we receive comes from a handful of intrepid scholars, doctors, and journalists who have taken the risk of “going inside,” usually under the aegis of one of the resistance groups. Their reports, covering a variety of aspects of the Afghan conflict, have included numerous accounts of atrocities and other human rights abuses since the Soviet invasion of December 1979.

During September of 1984, we went to the Afghan border—to Peshawar in Pakistan’s Northwest Frontier Province, and to Quetta in Baluchistan—to collect information about human rights violations in Afghanistan by interviewing some of the Afghan people who have sought refuge there. We had already interviewed Afghan refugees in the United States and Paris and had read extensively in preparation for our trip. Nothing, however, prepared us for what we were to see and experience in Peshawar.

The vast scale of the exodus—an estimated four to five million refugees in Pakistan and Iran, representing one-quarter to one-third of Afghanistan’s prewar population—is immediately apparent in Peshawar, where the largest concentration of the more than three million Afghan refugees in Pakistan has settled. It is hard to imagine what Peshawar—always a colorful frontier town at the entrance to the Khyber Pass into Afghanistan—was like before this transfiguring, heartbreaking influx.

Everywhere there were Afghans, most of them Pashtuns who have the same language and appearance as the Pakistanis of the Northwest Frontier Province, but who are ill suited to the passive life of the refugee. On the whole, they have not assimilated into Pakistani life. They are waiting—the women and children seeking food and shelter, the men seeking arms and support. Their goal is to return to Afghanistan, the only country they have known.

The refugees arrive in a steady procession. They come on foot over the mountains on journeys that often take a month or more. Their children and possessions are carried by horses, mules, or camels; their caravans are helpless targets for Soviet bombers and helicopter gunships. They come from every province in Afghanistan, every walk of life. Some have settled in the refugee camps around Peshawar. Others, wounded by bombs, mines, shellfire, or gunshots, are being treated in hospitals. Some have found homes and a purpose in Peshawar, working with one of the many Afghan political parties based there or with one of the relief organizations that are trying heroically to cope with the crisis. But most are just waiting, lost and unhappy, bewildered by the unexpected devastation of their lives and by what they have experienced.

We interviewed more than one hundred Afghans representing a cross section of Afghan society, old and young, men, women, and children. We met with educated people from Kabul—professors, doctors, teachers, students, lawyers, former government officials—and with Afghanistan’s leading poet in the Persian language, Ustad (Master) Khalilullah Khalili. We spoke with villagers—farmers, shepherds, nomads—driven from their land. We visited hospitals where we met paraplegics and amputees, victims of antipersonnel mines left behind by retreating Soviet and Afghan forces or of the camouflaged plastic “butterfly” mines that are dropped from helicopters and intended to maim, not kill, the shepherd children and their flocks. We met with political leaders and resistance commanders, including the brother of the legendary commander Ahmad Shah Massoud of the Panjshir Valley. We interviewed deserters—Soviet soldiers barely out of their teens, themselves victims of an unnecessary war. We even met a defector from the Afghan secret police, who described to us the inner workings of the KHAD (the Afghan secret police).

Advertisement

From our interviews, it soon became clear that just about every conceivable human rights violation is occurring in Afghanistan, and on an enormous scale. The crimes of indiscriminate warfare are combined with the worst excesses of unbridled state-sanctioned violence against civilians. The ruthless savagery in the countryside is matched by the subjection of a terrorized urban population to arbitrary arrest, torture, imprisonment, and execution. Totalitarian controls are being imposed on institutions and the press. The universities and all other aspects of Afghan cultural life are being systematically “Sovietized.”

It also became clear that Soviet personnel have been taking an increasingly active role in the Afghan government’s oppression of its citizens. Soviet officers are not just serving as “advisers” to Afghan KHAD agents who administer torture—routinely and savagely—in detention centers and prisons; according to reports we have received there are Soviets who participate directly in interrogation and torture. Moreover, the uncertain loyalties of the Afghans recruited into the army have apparently forced Soviet soldiers to take an aggressive military role. The Soviets have taken the lead in air and ground attacks on Afghan villages, looting, terrorizing, and randomly killing Afghan civilians—including women and children—in a variety of unspeakable ways.

Just about every Afghan has a story to tell. Our interpreters, our guides, people we met accidentally, had personally experienced atrocities as great as those experienced by the “victims” we interviewed. An Afghan doctor who had impressed with his gentleness and kindness when he interpreted for us in a hospital for war victims had a sudden outburst while we were leaving. “What’s the point of all this? People should know by now. There are no human rights in Afghanistan. They burn people easier than wood!” He went on to tell us that he had lost forty-two members of his family under the present regime and had just learned that two had been burned alive a few weeks before.

One day, on an impulse, we stopped to talk to a group of refugees camped by the side of the road, peasants who had arrived that morning from Nangarhar and Kunduz provinces. The stories they told were stories that we were to hear over and over again: “The Russians bombed our village. Then the soldiers came. They killed women and children. They burned the wheat. They killed animals—cows, sheep chickens. They took our food, put poison in the flour, stole our watches, jewelry, and money.” Two young women, encountered at random, had each lost five children in a recent attack. One of them, who had also lost her parents and sister, displayed the burns from bombings on the limbs of her remaining children, the three youngest, whom she had managed to take with her as she fled from her house when the troops arrived. “I don’t know how the days become nights and the nights become days,” she said, her eyes flashing in anger and desperation. “I’ve lost my five children. Russian soldiers do these things to me.”

The strategy of the Soviets and the Afghan government has been to spread terror in the countryside so that villagers will either be afraid to assist the resistance fighters who depend on them for food and shelter or will be forced to leave. The hundreds of refugee families crossing the border daily are fleeing from this terror—from wanton slayings, reprisal killings, and the indiscriminate destruction of their homes, crops, and possessions. We were told of brutal acts of violence by Soviet and Afghan forces: civilians burned alive, dynamited, beheaded; bound men forced to lie down on the road to be crushed by Soviet tanks; grenades thrown into rooms where women and children have been told to wait.

People coming from just about every area of Afghanistan—Western scholars, journalists, doctors and nurses, as well as the Afghan refugees and resistance fighters themselves—have supplied evidence of vast destruction: carefully constructed homes reduced to rubble, deserted towns, the charred remains of wheat fields, trees cut down by immense firepower or dropping their ripe fruit in silence, with no one to gather the harvest. From throughout the country come tales of death on every scale of horror, from thousands of civilians buried in the rubble left by fleets of bombers to a young boy’s throat being dispassionately slit by a Soviet soldier.*

Advertisement

This mass destruction is dictated by the political and military strategy of the Soviet Union and its Afghan allies. Unable to win the support or neutrality of most of the rural population that shelters and feeds the elusive guerrillas, Soviet and Afghan soldiers have turned their weapons against civilians. When the resistance attacks a military convoy, Soviet and Afghan forces attack the nearest village. If a region is a base area for the resistance, they bomb the villages repeatedly. If a region becomes too much of a threat, they bomb it intensively and then sweep through with ground troops, terrorizing the people and systematically destroying all the delicate, interrelated elements of the agricultural system. The aim is to force the people to abandon the resistance or, failing that, to drive them into exile.

While the terror has indeed desolated much of the countryside, it has failed to crush the resistance. None of the villagers with whom we spoke blamed the resistance fighters—the mujahedin—for their troubles. How could they? The mujahedin are their sons, fathers, brothers, husbands. The resistance and the civilian population are inextricably entwined. “We need our people,” a resistance commander told us. “But we are also responsible for them.”

During our visit we received evidence indicating that the Soviet and Afghan governments are changing their strategy and now seem intent upon ending the exodus to Pakistan. Perhaps they are alarmed by the huge refugee population in Pakistan and the international attention it must inevitably attract. Certainly they are concerned by the support that the resistance finds in Pakistan—a chance to rest, organize, rearm, and reenter, sometimes with foreign press, for the Afghan resistance has grasped the importance of the press in enlisting public support. We received reports that refugees on their way to Pakistan have been arrested by the Afghan militia or the KHAD, who turn them back, herding them toward their devastated villages or to the cities, already swollen with more than a million internal refugees. Those who persist in the trek to Pakistan increasingly risk attacks by bombers or the dreaded helicopter gunships. Along the arduous mountain trails used by refugee caravans are many tattered flags flying over hastily dug mass graves.

We also heard reports that Afghan citizens must now carry identity cards and obtain written permission to travel, and that the authorities are confiscating the homes of those believed to have gone to Pakistan. During our visit, the Afghan Air Force bombed the public market in a Pakistani border town, killing dozens of Afghan refugees and Pakistani civilians, one of an increasing number of such attacks, signaling that Pakistan is no longer a secure refuge.

This tightening of control over civilians remaining in the countryside mirrors the totality of the rule that has been established in the urban centers of Afghanistan. Professionals and academics have been killed, arrested, censored, or dismissed. Most of the Afghan intelligentsia are either in prison or in exile. University curriculums require study of the Russian language, Russian history, and Marxist-Leninist philosophy. Book publishing and the press are under strict censorship. Tens of thousands of Afghan youths are being sent, sometimes against their will, to study in the USSR. Children of nine and ten are being trained in Pioneer groups to inform on their parents and infiltrate the resistance. State-controlled agents and informers watch every office and classroom. It is estimated that tens of thousands of people are now in Afghan prisons where they have been brutally tortured and subjected to vile conditions.

We interviewed a twenty-one-year-old student who had been released from Pol-e Charkhi Prison in Kabul just two weeks before. His eyes bloodshot, his body tense, he nervously fingered his worry beads as he told us that if we mentioned his name in print his father and brothers in Kabul “will be finished.” After his arrest for distributing “night letters” protesting the Soviet invasion, he was subjected to routine torture—hung by a belt until he almost strangled, beaten until his face was twice its normal size, his hands crushed under the leg of a chair. He described an overcrowded prison cell with no windows, crawling with lice, and with only one pot for a toilet. Others told us about prison cells with one toilet serving five hundred people. Still others described cells with no bathroom at all, in which prisoners were forced to defecate in the room. Former prisoners told us about electric shocks, nail pulling, lengthy periods of sleep deprivation, having to stand in cold water, and other punishments. Many prisoners have been summarily executed.

Nor are women spared, a source of special torment to Afghan men as well, whose code of honor requires them to shelter and protect their women from the outside world. We heard of mothers who were forced to watch their infants being given electric shocks, and of Afghan men who were held in torture chambers where women were being sexually molested. A young woman who had been tortured in prison described how she and others had been forced to stand in water that had been treated with chemicals, which made the skin come off their feet.

An Afghan refugee, a former civil engineer from Kabul, described three women who were in the same prison as he: “In the night, many times, we could hear them crying. We did not know why—probably they were tortured. We could hear them crying many times.”

Many of the crimes already discussed are violations of the Geneva Convention. There are others as well, such as the deliberate bombing of hospitals and the summary execution of prisoners of war. While we did not investigate persistent reports of chemical warfare and other illegal weapons, we encountered the belief that the Soviets, at least at the start of the Afghan conflict, may have used Afghanistan as a convenient testing site for banned or experimental weapons.

In view of the outrageous policies and practices of the Afghan government and its Soviet allies, it is no wonder that they have refused to allow any form of international inspection. A request by Helsinki Watch to send an official fact-finding mission to Kabul has not been granted. The International Committee of the Red Cross, after two unsuccessful visits to Kabul, has been forced to set up medical facilities outside Afghanistan, taking wounded refugees from the border to Red Cross hospitals in Pakistan. As of this writing, the Afghan and Soviet governments have not agreed to cooperate with the special rapporteur on Afghanistan appointed by the UN Human Rights Commission. Only a few carefully selected foreign journalists have been permitted to visit Kabul and their visits have been strictly limited and controlled by the Afghan government.

In September Afghan and Soviet authorities served notice on Western journalists investigating the war when Soviet troops seized in ambush a French television reporter, Jacques Abouchar, who had entered Afghanistan illegally from Quetta. Referring to those who have been entering Afghanistan from Pakistan, Vitaly S. Smirnov, the Soviet ambassador to Pakistan, warned that “from now on, the bandits and the so-called journalists accompanying them will be killed. And our units in Afghanistan will help the Afghan forces to do it.”

To close the mountainous Pakistan-Afghanistan border will be a monumental undertaking, if not altogether impossible. Yet the Soviets have embarked on this course, not only to prevent the flow of arms to the resistance, but to impose a blackout on news from Afghanistan.

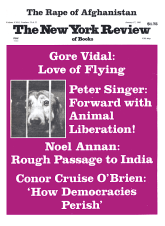

This Issue

January 17, 1985

-

*

While we received some reports of killings of civilians by Afghan soldiers, most of the killings we documented involved Soviet soldiers, sometimes assisted by a few Afghans acting as guides or interpreters. In each interview clear distinctions were made among: Soviet troops (shurawi) or Russian troops (rus); government forces, sometimes called askar-e daulat‘, sometimes askar-e Babrak; and PDPA members, who were identified as Khalqi or Parchami. There is reason to believe that Soviet officers are distrustful of the Afghan soldiers, most of whom are reluctant draftees with a high rate of desertion or of defection to the resistance.

↩