Prince Norodom Sihanouk was king of Cambodia from 1941 to 1955. After forcing the French to grant independence to Cambodia, Sihanouk abdicated and ruled as an elected head of state until he was overthrown in a coup d’état in 1970. Sihanouk became the nominal head of an opposition coalition, dominated by the Khmer Rouge, which defeated General Lon Nol’s Khmer Republic in a civil war which ended in 1975. The Khmer Rouge put Sihanouk under house arrest where he remained until the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in January 1979.

In 1982 Sihanouk became president of the tripartite “Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea,” which includes the Khmer Rouge and forces loyal to former Prime Minister Son Sann. The coalition is fighting a guerrilla resistance against the Heng Samrin regime, which is backed by the Vietnamese occupation and controls most of Cambodia. The coalition government, however, is recognized by the United Nations and most of the countries outside the Soviet bloc as the legitimate government of Cambodia.

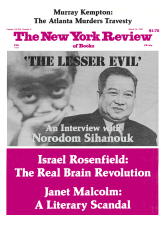

Thus Sihanouk is once again de jure head of state. Recently, on February 9, he visited the Cambodian town of Phum Thmey in the coalition’s “liberated zone” and there accepted the credentials of ambassadors from Senegal, North Korea, Bangladesh, and Mauritania. We spoke with him late last year in New York, where he had just finished addressing the United Nations General Assembly. The interview was conducted in English.

David Ablin

Marlowe Hood

Q: Your Royal Highness, we would like to ask you some questions about the contemporary situation, but since your views on that are better known, we would like to begin by asking you a few historical questions. In light of the events in Cambodia of the last fifteen years, is there anything that you would have done differently from 1945 to 1970?

A: You know I have always been dedicated to my homeland. I try to give happiness, some prosperity, and education to my people. I want my country to be independent, always independent. I have to defend my convictions as a patriot and as a national leader. I have done my best, but as a human being I cannot be perfect, nobody is perfect. Even your presidents in the contemporary history of the United States have only been able to do their best. President Carter is now so often criticized, but he did his best, and President Nixon as a patriot, as a human being, he could not avoid mistakes. I have made mistakes, but I cannot blame myself, not because I have pride, but you know I am not God, I am not a Buddha, I am not Christ.

There are good and bad aspects in me as a normal human being, but you must compare me with the other leaders in the contemporary history of Cambodia. I don’t think that Lon Nol was better. Lon Nol enjoyed your full support during the war and he lost the war. The Americans lost the war in Indochina because America relied on people like Ngo Dinh Diem, Nguyen Van Thieu, and Nguyen Cao Ky in South Vietnam, and Lon Nol and Sirik Matak in Cambodia. So the final results were that you gave Indochina and many advantages to the communists. I can quote the late Vice-Premier Sirik Matak who was very, very pro-American. He told the American press that the United States, by supporting corrupt and non-popular regimes like Lon Nol’s, indirectly served the cause of communism in Cambodia.

About the destruction of Cambodia there are two versions, two theses, one by William Shawcross, one by Henry Kissinger. So it is up to you to see whether Shawcross is right or Kissinger is right. May I quote here Sisowath Sirik Matak’s declaration to The New York Times on March 23, 1973:

General Sirik Matak reflecting on the republican regime that he helped to create three years ago after the overthrow of his cousin, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, said in an interview, “I believe that this regime must not survive and will not last. It is not supported by the people.” The general said sadly that if a free and honest election were held now with Prince Sihanouk and Marshal Lon Nol as candidates, the prince would win easily. Sirik Matak said: “If the United States continues to support such a regime, we will fall to the communists. When you support a regime not supported by the people, you help the communists.”

My friend Michael Mansfield made a declaration in Denver, Colorado, on October 31, 1972: “Senator Mike Mansfield pledged to push for the return to power of Cambodia’s Prince Sihanouk. He was the best ruler in Southeast Asia.” The Far Eastern Economic Review of November 18, 1972, stated: “In retrospect some people are discovering the wisdom of Sihanouk.” I can quote in French François Nivolon in Le Figaro for December 4, 1973:

Le paysan moyen, indifferent aux problèmes de politique internationale, raisonne simplement: “Quand Sihanouk était là, il n’y avait pas de guerre, et nous n’étions pas pauvres. Maintenant, il y a la guerre, et nous sommes pauvres.

The peasants in Cambodia told François Nivolon that when Sihanouk was in power in Cambodia, “We were not poor and now we are poor.”

Advertisement

No, I don’t think I was a perfect leader. I was far from being a perfect leader. But if people decide to consider Sihanouk a bad leader, I was certainly less bad than Lon Nol and Sirik Matak, less bad than Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, and Khieu Samphan, less bad than Heng Samrin and Hun Sen. People ignore that I helped build hospitals for my people. They ignore that I built many, many schools, colleges, and universities for the youth. Many people believe that I did not build any dams or factories to develop the economy of my country, but the facts show that I have done much for my people. And they accused my regime of being corrupt, but the ones who made a coup d’état against me, Lon Nol, Sirik Matak, and so on, were responsible for corruption in my regime. All those so-called Khmer republicans were monarchists. They served the monarchy and they were corrupt.

I have no wealth. I now survive thanks to China. Without the People’s Republic of China I could not have survived since the coup d’état of Lon Nol. But they can survive. Lon Nol is in California, his wife is very rich, while my wife and I have our clothes thanks to China and North Korean President Kim Il Sung. I have no money. If I had been corrupt, I could afford to have a good life. But I have a good life thanks to friends like Chou Enlai, the Chinese leadership since Mao Tsetung, and President Kim Il Sung.

I don’t pretend, I repeat, to be perfect, but when Cambodia was under my leadership, Cambodia was in much better shape than under Lon Nol and then under Pol Pot and now under Heng Samrin and the Vietnamese. And as far as my resistance against foreign intervention in my country is concerned, I don’t have to criticize myself because I have always been anticolonialist, anti-imperialist, and anti-expansionist. I had to fight against the French in order to get from them full independence for my country. I like France and the French people and France made me king in 1941, but I had to get for my country full independence. I got from France full independence in 1953.

After 1953 I had difficulties with the United States. At that time you know the United States was not like it is now. Now it is all right, but before, it did not allow my Cambodia to be really free. United States aid was conditional and the United States did not approve of my neutralist policy. As far as the compromise I made with the North Vietnamese and the Vietcong during the Indochina war is concerned, I could not avoid such a compromise. Lon Nol, after making a coup d’état against me in 1970, told the Vietcong and the North Vietnamese, “You go home. I won’t allow you to have sanctuaries in Cambodia.” The result was that the North Vietnamese and the Vietcong developed the sanctuaries and finally occupied the whole of Cambodia. Despite the intervention of the American Army, the American Air Force, and the South Vietnamese Army, everything was lost to America and to Lon Nol. They lost everything to the Vietcong and to the North Vietnamese.

I had to balance the influences of the West and the East and I had to walk on a tightrope. That was unavoidable. I don’t think that I was guilty for trying to safeguard the essential interests of my country in order to let my country survive. We had to face the misunderstanding of the USA on the one hand, and the North Vietnamese and Vietcong pressure on the other. The lesser evil consisted for me of having a compromise. So I had to let the Vietcong and the North Vietnamese have small sanctuaries near the border of South Vietnam and inside Kampuchea. This I could not avoid. It was difficult for a leader in Kampuchea to behave otherwise because the situation was so difficult, so difficult. So in brief, I don’t have to criticize myself. You can criticize me, but I cannot, because I was guided always by my conscience.

As far as the Vietnamese themselves are concerned, if I could have remained head of state, then I’m sure that I could have prevented them from invading Cambodia. But Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge made provocations against the Vietnamese from when Pol Pot took power in 1975 to 1977. In 1978 Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge had more and more clashes with the Vietnamese. The Vietnamese and the Khmer Rouge won the war against the Americans but there was a split among them as winners after the withdrawal of the United States troops. China and the Khmer Rouge were on one side, Russia and North Vietnam were on the other side. The 1979 invasion of Cambodia by Vietnam was a result of this dispute. So you know it is not my fault. I was a prisoner in the hands of the Khmer Rouge. I could not save my country. Now everybody wants me to save my country, but I am not a god, I am powerless. But I am doing my best as the leader of the coalition in the process of resisting the Vietnamese.

Advertisement

Q: What do you think the Vietnamese goal is in Kampuchea? What do you think they hope to attain?

A: There is a split among the communist powers who won the war. The People’s Republic of China and the USSR supported the Vietnamese and the Khmer Rouge when they had to fight against the USA and its protégés and satellites in Saigon, Vientiane, and Phnom Penh. The communists won the war in 1975 and then they split. If I may say so, there are now two communist churches, one with Peking as the leader and another with Moscow as the leader. So now we, Cambodia, are the victims of the dispute between the two communist camps. I personally, as a patriot, want my Cambodia to be safe. What people now call “the problem of Kampuchea” can be solved only if China and the USSR succeed one day in improving their relations. Otherwise, if the dispute between the two communist camps continues, we will not see the end of the misery of Cambodia and the Cambodian people. The two camps want to dominate the former French Indochina because Indochina, including Cambodia, has a very important strategic position in Southeast Asia and in Asia. That is the reason why the French occupied Indochina after 1860; and after the French, the Japanese came into Indochina during the Second World War; and after the Second World War, the Americans came into Indochina; and after the departure of the Americans so came the Russians.

As far as Vietnam is concerned, people must know that the Vietnamese have difficulties at home. North Vietnam is over-populated. They lack land and food for their own people. So they send more and more Vietnamese settlers into Kampuchea in order to take our land, to take our food, to exploit our natural resources. The Russians and the Vietnamese want to replace the French in Laos and Kampuchea because Kampuchea in particular and the former Indochina in general have important strategic positions. The Americans also saw that Southeast Asia has a very important strategic position so they intervened in Indochina in the 1950s and 1960s. Now, despite the difficult situation in the Philippines, the Americans have to stay because they need strategic bases. Despite your desire to improve your relations with Peking, you have had to stay in Taiwan; you have had to stay in South Korea—all because those countries are very important strategically. So it is for the Russians and the Vietnamese: they had to occupy strategic positions. That is the reason why they are in Kampuchea, in my country.

The only way to solve the problem of Kampuchea is to get a compromise between Moscow and Peking in the form of the neutralization of Kampuchea. But the Chinese told me that they were not ready to have a compromise with Vietnam and the Russians about Kampuchea. They want Kampuchea to be liberated 100 percent from the influence of Vietnam and the Soviet Union.

Q: In a recent interview, in reference to the military situation, that is, the coalition government’s forces fighting a resistance war against the Heng Samrin government, you said, “I am realistic enough to say that we are not going to win.” I wondered if, in that case, you could envision a solution that starts with the isolation and the disarming of the Khmer Rouge?

A: We have to be realistic. We know that the Khmer Rouge are strong enough to defend themselves against possible attempts to disarm them. And they have a staunch ally, the People’s Republic of China. Recently when Prime Minister Son Sann, Vice-President Khieu Samphan, and myself met with strong man Deng Xiaoping on the occasion of the thirty-fifth anniversary of the People’s Republic of China, Deng Xiaoping told us China will support and help only a tripartite coalition, not a bilateral coalition. Pol Pot, Khieu Samphan, and the Khmer Rouge must not be wiped out. Khieu Samphan himself, on behalf of the Khmer Rouge, told the ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] countries and myself that the Khmer Rouge wanted to stay in the coalition as a loyal partner of the nationalists of Son Sann and Sihanouk and will not accept being separated. Pol Pot wants to remain in Cambodia and nobody will succeed in creating a split among the Khmer Rouge. Pol Pot and all the leaders of the Khmer Rouge movement will remain united and nobody will be allowed to disunite or disarm them. So to the ones who want to disarm the Khmer Rouge I say, “Please send one hundred divisions from your country to Cambodia to wipe out the Khmer Rouge. I am powerless. I cannot disarm them.”

Q: Then it would be all right with you if the United States came in and eliminated the Khmer Rouge?

A: No, I simply told you, told the ones who want to wipe out the Khmer Rouge, to please intervene yourself if you want to wipe out Pol Pot. I have to liberate my country from Vietnam. There is another danger for Cambodia; it is not Pol Pot. It is Vietnam. I must fight to liberate my country. Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge are not going to win. You yourself quoted me. You said that I used to say that we are not going to win. I am not very optimistic about the outcome of our struggle. That is the reason why I must concentrate on fighting the Vietnamese and liberating my country through an international conference. I wanted to persuade Vietnam to accept an international conference to solve the problem by working with us, the United States, the other permanent members of the Security Council of the United Nations, and the ASEAN countries.

But how can you get to the problem of Kampuchea unless you weaken the Vietnamese in the battlefield? So my job does not consist of concentrating on Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. I must concentrate on the very mortal Vietnamese danger. I don’t ask the United States to send anybody to fight against the Khmer Rouge; they ought to organize themselves, their expedition, their intervention.

Q: In 1977, Senator George McGovern said that the United States should invade Cambodia and overthrow the Pol Pot government. Do you think that in light of what has happened since then, that would have been a good thing for Kampuchea?

A: You know there is a problem about human rights. Senator McGovern wanted an intervention by the United States into Cambodia to save my people. Your government rejected the proposal of Senator McGovern under the pretext that a state has no right to cross the border of another sovereign state. So the question is this: must we reject this law consisting of not violating the borders of a sovereign state even if a people is dying and the government in that state is practicing a policy of genocide? Personally, I think that we must reject such a law. If, in a sovereign state, you see genocide being practiced by the government against its own people, as Pol Pot did, I think the international community should not be selfish and hide itself behind the curtain and the pretext of its not being possible to intervene because nobody has any right to cross the border of a sovereign state.

We must allow democratic states to intervene in order to save dying people. If you see a boat sinking in the sea, like those of the boat people from Vietnam, do you use your ship to save them or not? You must intervene even if you are outside your national border. So, I think that since you allow yourself to save people in a sinking boat in the ocean outside your national border and in international seas, so, you must think that it is an international duty to intervene in favor of dying people.

I think that Senator McGovern was right and your government was wrong. You always have to save people. The Americans intervened in 1970 in order to “save” a neutralist country, an independent country under Sihanouk. So I don’t understand. But if the United States were now to go to Cambodia, it would really be wonderful. Why? Because you would be saving the Cambodian people from Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge and from the Vietnamese colonialists. That would be all right. When Cambodia is under Pol Pot, you don’t save Cambodia; when Cambodia is under the Vietnamese, you don’t save Cambodia; but you save Cambodia when Sihanouk was the leader there because I had to be wiped out. I don’t understand.

Q: Do you think now, in looking back, that your support of the Khmer Rouge, after you were overthrown, was a mistake?

A: You know the Khmer Rouge, they won the war thanks to China and to Vietnam….

Q: With much help from your influence with the peasants and your popularity.

A: Yes, I had my part also in the mistake. But let me add this: At the time in 1972 when there was a honeymoon in Peking and Shanghai between President Nixon and Chou En-lai, the Khmer Rouge were still very weak. They were not so strong, and their sponsors, the North Vietnamese and the Chinese, wanted them to be just one part of a national union government under my chairmanship. Chou En-lai and the North Vietnamese wanted me to go back home to Phnom Penh in order to preside over a tripartite national reconciliation government with Sihanoukians, Lon Nolians—the ones who had made the coup d’état against me—and the Khmer Rouge. Actually, I wanted Kissinger and Nixon to see about such a compromise, but Kissinger and Nixon rejected the proposal made by Prime Minister Chou En-lai on behalf of our camp, our side. That was the last chance for everybody, the Americans and Cambodia, to be saved.

I, and Cambodians inside Kampuchea at that time, had not love, but esteem for the Khmer Rouge. Nobody could imagine that they might be the monsters they were after taking power. At that time everybody, even my compatriots in Phnom Penh under the leadership of Lon Nol, believed sincerely that the Khmer Rouge, although communists, were also non-corrupt, good democrats and dedicated to the people.

They wished that the Khmer Rouge would take power because they were very disappointed with Lon Nol, Sirik Matak, and that very corrupt regime. Lon Nol and Sirik Matak had told them that corruption came from Sihanouk and that the new regime would not be corrupt. But, in fact, after the withdrawal of Sihanouk, the regime became…I quote Sim Var, the number one anti-Sihanouk Lon Nolian, and former prime minister of Cambodia, who told the press, “Now without Sihanouk we are one hundred times more corrupt.” People were really disappointed vis-à-vis Lon Nol and his regime and wanted the Khmer Rouge to take power.

So, not only Sihanouk, but the youth, the intellectuals, everybody believed that with the Khmer Rouge, at least we could have a clean republic, a clean regime, and even democracy. And the Khmer Rouge themselves continue to call themselves Democratic Kampuchea! Then we believed that they could be really democratic, but it became apparent very, very quickly after the takeover of Phnom Penh by the Khmer Rouge that they were monsters. So, you know, I must point out that during the years 1973, 1974, and until April 1975, people in Lon Nol’s regime in Phnom Penh said to the Americans, to your government, “The Khmer Rouge, they are patriots like us Lon Nolians; they are good people. Sihanouk is very bad. We have to try to get the Khmer Rouge into the government, and we might have a good solution to the crisis in Kampuchea.” So, the pro-American Cambodians themselves were very pro-Khmer Rouge and now they are criticizing me for my so-called complicity with the Khmer Rouge. I was perhaps guilty, but I was not the only man who had a false opinion about the Khmer Rouge.

Q: What is your interpretation of the reasons for their behavior after they came to power? Why were the Cambodian communists so different from those in Vietnam?

A: They had much pride. When I returned to Kampuchea with the permission of the Khmer Rouge in September of 1975, I met with Khieu Samphan, Ieng Sary, the number two man of the regime and Son Sen who is minister of defense to this day. They told me then that they wanted to win the race even against their dearest allies, the Chinese. The Khmer Rouge told me:

We want to have our name in history as the ones who can reach total communism with one leap forward. So we have to be more extremist than Madame Mao Tse-tung and the Cultural Revolution leadership in China. We want to be known as the only communist party to communize a country without a step-by-step policy, without going through socialism.

I repeat, the Khmer Rouge have much pride, too much I may say.

I met Pol Pot for the first time in March 1973, when I visited the liberated zones of Cambodia during the war. Pol Pot’s name at that time was Saloth Sar. I did not know he was the very master of the Cambodian communist movement. He did not reveal himself as a leader, and during our meetings he had a seat behind the other leaders. I believed very naively—I was very naive vis-à-vis the Khmer Rouge—that Khieu Samphan was really the master of the movement. Pol Pot was already the leader, but preferred to show Khieu Samphan as the leader. Now again, he is behind Khieu Samphan. When Pol Pot needs to hide behind somebody, he does. He was very charming, very nice, very friendly to me, and very discreet.

The Khmer Rouge won the war in April 1975, but they did not allow me to go back home in April. They said that they had to solve many, many problems before having the opportunity to receive me in Kampuchea. So, I had to stay in Peking until September when I went to Kampuchea on the invitation of the Khmer Rouge. I went to Phnom Penh, but I did not see Pol Pot. I saw him for the second and last time on January 6, 1979, one day before the Vietnamese entered Phnom Penh. He wanted me to defend the cause of Democratic Kampuchea at the UN Security Council. I went to New York after that to present the case of Kampuchea which was being invaded by Vietnam. That was the last time I saw Pol Pot.

That was one reason. Another reason is this. The Khmer Rouge say that it is their duty to act in this way in order to serve the poorest class. Their philosophy is this: the merchants, the intellectuals, the princes, and the bourgeois are all corrupt and enemies of the people in Kampuchea. Even the rich peasants, since they are rich, exploit the poor peasants, according to the Khmer Rouge. The intellectuals are all corrupted with money or are intellectually corrupt. Even if they are clean civil servants or teachers, they are corrupt intellectually. So, all those corrupt people, enemies of the people of Kampuchea, must be wiped out. They have to wipe out, to liquidate, all the enemies of the people, that is to say the enemies of the poorest. They want to build up a new society with only the poorest Cambodians. The Khmer Rouge themselves are not poor; they are intellectuals. But they do not want to have opponents.

There is another reason why they liquidated so many people. They are very ambitious, ambitious for themselves, ambitious for their ideology, for their very special philosophy. The Khmer Rouge feel enemies and see enemies everywhere, all around them. Even close to them, like Stalin. They are very Stalinian. You can understand them a little if you have studied Stalinism. Stalin was responsible for so many deaths. He practiced genocide on his own people. Not just on the Jews, like Hitler. But also opponents whom Stalin saw even in the Kremlin. Enemies everywhere, spies from America, spies from capitalist countries, spies and traitors everywhere. Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, they are maniacs. They saw enemies everywhere. They told me: we had to liquidate all the enemies of our country, otherwise we cannot save the country. I think they, themselves, could not be saved, so they had to liquidate all their opponents, even communists.

That is the reason why they liquidated communists. The ones who had studied in Moscow, for instance, the ones who had studied in capitalist countries or in America: even if they were leftists, they had to be liquidated. After liquidating the bourgeois, the rich merchants, the rich peasants, intellectuals, they also had to liquidate people all around them. Why? There was a split among communists in Cambodia. There were Cambodian communists who chose Peking and others who chose Hanoi and Moscow. Heng Samrin and his group chose Hanoi and Moscow. In 1977, when it appeared that their group was defeated by Pol Pot and the pro-Peking group, Heng Samrin and Hun Sen sensed the liquidations and fled into Vietnam. They came back into Kampuchea behind the invading Vietnamese armed forces in December 1978. But they are all Khmer Rouge. They are all responsible for the genocide. They share the same opinions with Pol Pot as far as the necessity to liquidate the bourgeois, the princes, and so on.

These are some of the reasons the Khmer Rouge became very cruel. But may I add this: there are people like Hitler. They are cruel. Stalin, Ivan the Terrible. There are cruel people. Genghis Khan. There are many cruel people. Some scholars say to me: yes, one person, one man like Pol Pot or Hitler, but how can you explain that so many Khmer Rouge became like Pol Pot? But no, look at Hitler, please. Hitler was not alone in being very cruel. All around Hitler, you had Himmler, you had so many butchers, and during the war in France, in Yugoslavia, etc., there were so many German commanders, officers, Gestapo leaders, and SS leaders. They were very, very cruel; Hitler was not alone. Hitler succeeded in uniting and gathering all around him many, many cruel people. Pol Pot did the same.

And, you know, people believe that Khieu Samphan is not cruel. He is not responsible for the physical killing of men; but in the library of the Sorbonne, there is a book by him in which he says that the leftists had to fight against all class enemies, the ones who are enemies of the poorest. They had to take sides to be with the poorest against all the others. Khieu Samphan did not write, “We must kill,” but he writes, “We must get rid of these people.” It is the same…the same result.

Q: But in the United States and the West, the governments are coming under very severe criticism for working with and protecting some of the ex-Nazis after World War II, like Klaus Barbie.

A: Yes, Klaus Barbie.

Q: Isn’t there an analogy between working with Pol Pot now and working with the Nazis after World War II?

A: Not in our century, but a few centuries ago, a French philosophe said: States are monsters, cold monsters. Les états sont les monstres froids. That means that the duty for a state is to serve its own selfish interest. Nobody can criticize the United States administration when it sometimes has to compromise with a nondemocratic regime or people. And, you know, now some Americans tell me, “We Americans don’t understand why you, Sihanouk, are with the Khmer Rouge once again. You know what they have done to their own people.” Yet the United States keeps Mr. Son Sann in high esteem. Mr. Son Sann was not with the Khmer Rouge during the 1970s, unlike Sihanouk. But Son Sann is now with the Khmer Rouge. Son Sann, a very respectable man, is with the Khmer Rouge because he thinks, rightly, that now we are facing a more mortal danger for Cambodia than the Khmer Rouge danger.

We have to put aside things of the past. We have to put aside the Khmer Rouge case and concentrate on fighting against the Vietnamese. Otherwise, one day there will be five million Vietnamese in Cambodia. Cambodia will be lost to the Cambodians, and Cambodia will be a colony of Vietnam. So we have to fight. If we are not with the Khmer Rouge, we have no means to fight as nationalists, because China would not provide ammunitions, weapons, or financial aid. ASEAN would provide nothing, would give nothing to the nationalists, because we would be just rebels. ASEAN is not able to help rebels, because ASEAN would then have to allow other countries to interfere in the internal affairs of ASEAN countries where they are facing their own rebel problems in Thailand, in Malaysia, in Indonesia, in the Philippines, and perhaps Singapore also.

That is the reason why ASEAN told Son Sann and his followers, told Sihanouk and his followers, please enter the legal state framework of Democratic Kampuchea so that we can help you. Then we help not rebels, but a legal state recognized by the United Nations. We can then help the Kampuchean people and give all facilities to a sovereign state which is a victim of foreign aggression. Vietnam is the aggressor. Now Son Sann and I are working at the UN. Why? Because if we don’t enter the legal framework of Democratic Kampuchea, we would have to protest against the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in the streets. In the streets, just like some Afghan people in New York. But nobody listens to them. They cannot get for their country an independent and free Afghanistan.

If Son Sann and Sihanouk refrained from entering the legal framework of the state of Democratic Kampuchea, the Khmer Rouge left alone would finally lose the seat of Kampuchea. That would be the first step toward the recognition of the Heng Samrin regime by the international community represented by the UN. The day the seat of Kampuchea goes to Heng Samrin, Cambodia will be lost for the Cambodians and will forever be a province of Vietnam. The United States has to think about the interests of the free world, because Vietnam in Cambodia and the Soviet Union in Indochina are threatening the free world: the non-communist countries, ASEAN, and free, democratic countries.

That is the reason why before the forming in 1982 of the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea, the United States had to vote in favor of the Khmer Rouge in 1979, 1980, and 1981. I told those Americans who did not understand my joining with the Khmer Rouge to please look at Son Sann who also is joining with the Khmer Rouge, and to please remember that the United States itself voted regularly for the Khmer Rouge at the UN. I don’t criticize the United States because you were interested in two things. One is the safeguarding of the interests of your country as the leader of the free world. You must fight indirectly against Vietnamese expansionism in Indochina, in Southeast Asia, and Soviet hegemonism there by voting in favor of Democratic Kampuchea.

Two, you are genuinely friends of the Kampuchean people, and you want the Kampuchean people to be liberated, not to become a province of Vietnam. You have so many allies, and we owe you so much. Each year we win about ninety votes to twenty in the credentials vote. The UN resolutions for the withdrawal of Vietnamese troops, the condemnation of the Vietnamese occupation, and the recognition of the Kampuchean people’s right to self-determination get 105 votes with only twenty-five or twenty-seven or so against us. We get many votes thanks to ASEAN, thanks to China, thanks to our own efforts, but thanks also to the United States, because you have so many allies. You are very prestigious and help us a lot in such victories. You are doing that because if you let down Democratic Kampuchea, the UN seat of Kampuchea will first be declared vacant and, finally, the seat would go to the Vietnamese. If it goes to Heng Samrin, it is not going to the Kampuchean people, but to the Vietnamese. You know you have to practice such compromise.

It is a policy of states; states must not be sentimental. You have no sympathetic feelings vis-à-vis the Khmer Rouge. Nor do I. But we have to accept such a compromise. It is not very clean, not very clean. I don’t speak about you, but even myself; it is not very clean to be with the Khmer Rouge. I feel very uncomfortable; I suffer very much. I have lost five children, fourteen grandchildren at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. So many innocent people died. My chief of protocol, Madame Khek Sidsoda [the Prince gestured toward Madame Khek across the room], has lost her parents, her sisters, and her cousins who were tortured to death. So nobody likes the Khmer Rouge, but we have to behave like that. Why? Because there is the danger of Vietnamese expansionism and Soviet hegemonism and nondemocratic, very antifree people, governments, and states. Those states are very dangerous; we cannot allow them to go further.

Q: Having written about Cambodia, we would be very interested in knowing which Western writers since 1941 you have found to be particularly insightful about your country.

A: You know, about me in particular they are not very friendly, but there is no complaint from me because I respect your democracy, you are free. But it seems that it is not always very equitable. But I don’t express any complaint. I can’t say that I am very objective because you know each individual has his own passions, his own way of thinking, his own convictions, and even in all intellectual honesty, people can be wrong. I can be wrong myself about my policy, about my way of thinking, the choices I have made for instance about the Khmer Rouge and so on. Nobody, I repeat, is perfect as a human being. I apologize if I said words about myself without being critical. So many have criticized me already, I don’t need to criticize myself. I am not selfish, but I don’t think I have to criticize myself. I do have to give you some explanations about my choices, my policies of the past, in the present. I have to give you some explanations because I was, and am still, guided by my conscience and my own convictions. I may be wrong and I might have been wrong in the past, so I understand the people who criticize me in their books and in their articles.

For instance, Mr. Martin Herz. I will not accuse him of being an agent of the CIA, but diplomat Martin Herz dislikes me very much. So, in the libraries here, in Australia, and elsewhere, people always consult Martin Herz’s book, A Short History of Cambodia. According to Herz, Sihanouk is very bad and Son Ngoc Thanh of the CIA and of the Japanese fascists is the true champion of Cambodian independence. So, even now there are scholars who have gotten their inspiration from Martin Herz’s book.

I don’t criticize; I respect your democracy. In general, I think the American scholars, the people, are objective. In the writings and the sayings of each man or woman, there is a mixture of objectivity and subjectivity. Even Henry Kissinger says in his books nice things that conform with facts or historical realities, but many details or many lines also were dictated by his own way of thinking, his own convictions, and his desire to appear innocent. Nixon also. Even Shawcross is not always objective; he was more or less guided by his prejudices vis-à-vis Kissinger it seems. So nobody can claim he is 100 percent objective. We are more or less subjective as human beings. I think that in brief, American writers are good writers. They are honest. I respect and admire your virtues, if I may say so. I don’t flatter you because, as your notice, I have been candid and very frank. I don’t flatter.

This Issue

March 14, 1985