In England the police can arrest you on no more than “reasonable suspicion” that you have committed a crime. This includes possessing drugs or carrying an “offensive weapon,” which can cover a multitude of objects. If you are arrested, the police officer in charge of your case may deny your request to see a lawyer on the ground that this would impede the progress of the investigation. You may be held incommunicado by the police for interrogation up to thirty-six hours and, under a recent statute, a magistrate can extend this period up to ninety-six hours. When you do appear in the Magistrates’ Court there is no guarantee, if you are poor, that you will be assigned a lawyer, unless the case is one of some gravity. A lawyer may be present in the court to advise defendants but you may not be sure for whom he works and at best you can have only a brief, huddled conference with him.

Even if you have a lawyer, you will not be permitted to sit with him but will have to stand in a large elevated box. If you have the misfortune to be charged with a serious crime you may be denied bail and may have to wait months for a trial, locked for more than twenty hours a day in a small cell with two other prisoners and one communal bucket for your bodily needs. If eventually you are convicted and kept in prison you should not be very hopeful that what you see as an injustice will be corrected on appeal. The appeals court will not receive any written brief but will only listen to an oral presentation. Very few convictions are reversed.

Yet many American observers, including Chief Justice Burger, regularly point with admiration and envy to the English system as one we should strive to emulate. They have now been joined by Michael Graham, a professor of law, whose book advocates that by copying the English prosecution and trial process we may find the answer to some of our criminal justice problems.

There is, of course, a dark side to the explanation. American criminal procedure has paid close attention to the rights of suspects and defendants for no more than twenty-five years. There are those who look back nostalgically to a more authoritarian system, unhampered by the obstacles thrown up by recent efforts to protect individual rights. In legal circles this is often reinforced by toadying to the English, whose bewigged but mediocre appellate judges are treated with an absurd reverence by some American lawyers. Many people are unaware that serious crime continues to increase in Britain while it has leveled off in the US.1

But to dismiss the envy of the English courts as merely a reactionary response would be a mistake. Some aspects of English criminal procedure understandably have a special appeal for Americans who find our criminal trials slow-moving, expensive, and inefficient. Professor Graham gives us a useful account of the distinctive features of the British system in his book. The most general and conspicuous difference between the two systems is the comparative simplicity of English trial procedures and the absence of the unrelenting emphasis on adversary tactics that characterizes American trials.

In England, for example, the law of evidence is applied in a relaxed way. A lawyer seldom objects to another’s questions. Exhibits, as Graham points out, are introduced with considerable informality, in sharp contrast to the tedious haggling common at American trials. Written motions are discouraged by English judges. Very few issues can be raised in pretrial motions. Counsel steer away from controversial tactics and make informal agreements outside the court-room. English barristers seem less involved personally in their cases than American attorneys. Wearing identical robes, the prosecutor and defense counsel sit close together, far from the accused, and their advocacy is only faintly animated compared with that of lawyers in an American criminal trial. Professor Graham, like others, finds much to admire in this easy style of trying a case. It naturally leads to relatively swift trials as well as an appearance of smoothness and order.

But even if this admiration were well founded, it would not offer much basis for the reform of our own procedures. The English way of doing things is the product of slowly developed practices, of ancient modes of professional organization, and, indeed, of a particular national temperament. The muted adversarial tone in England derives from the strong sense, shared by a small, intimate profession, that a cool detachment ought to characterize the trial of a criminal case. Departing from this tradition and adopting a contentious American style of advocacy would lead only to amused disapproval and the loss of professional esteem as well as business. This detachment tends to be enhanced by the fact that the prosecutor in a jury trial in England is a member of the private bar who next week may appear for the defense in another case. The defense barrister, moreover, may never have seen the defendant until the morning of the trial, since the solicitor usually does most of the work until that point.

Advertisement

It would be impractical to think of dividing the American profession into trial lawyers and nontrial lawyers on the English model, or of abolishing American public prosecutors’ offices. It would be even more foolish to suppose that such changes would be accompanied by less contentious advocacy; and it is far from clear that such developments would be welcomed in any case. English trial methods owe a great deal to the camaraderie between bench and bar which may often put a higher value on “civilized” behavior between colleagues than on pressing fiercely for a client’s vindication. Persistent probing into the provenance of a document or into the chain of custody of narcotics may be “bad form” at the English bar, but defendants have been shown to be innocent in the United States by such practices. Most English barristers are very reluctant to cross-examine police officers aggressively in order to show that they are lying. This may have something to do with a counsel’s hope that he may be retained to prosecute for the Crown next week. A bureaucracy of full-time prosecutors has its merits.

Not only does Graham too lightly assume the superiority of the English bar, but he pays too little attention to a difficulty in principle that lies in the way of our emulating the English. The procedures that complicate and prolong American trials usually have to do with some constitutional requirement. For example, choosing the members of a jury is a perfunctory matter in England and barristers are not permitted to engage in the American “voir dire,” in which potential jurors are questioned, sometimes at length, in order to introduce them to the issues in the trial and to probe for opinions or traits that might lead to a decision to challenge the juror. While the voir dire is not itself explicitly required by the Constitution, it can be argued that it is indispensable for securing the impartial jury that the US Constitution demands.

Again, the calm pageantry of the English trial would be impossible without the strong management of the English judge, who questions witnesses, silences counsel, and sums up the evidence to the jury with pointed evaluations of his own. These remarks to the jury sometimes give a clear indication of the judge’s thinking on the defendant’s guilt or innocence. Conduct of this sort by an American judge would often be found by an appellate court to constitute a denial of the defendant’s constitutional rights to counsel and due process.

Of course, this does not mean that the trial practices that have grown out of current constitutional interpretations ought to be regarded as inviolate. Graham, for example, makes an attractive argument that the Warren Court made a mistake in 1965 when it decided that the privilege against self-incrimination, incorporated in the due process clause, renders it improper for a judge to comment adversely to the jury on a defendant’s failure to testify.2 Together with other rules of evidence this has now made it rare for the accused person to testify at all. In England, where his failure to do so can be the subject of sharp comment, he usually testifies.

Concerning the large moral questions underlying legal procedures, however, the English criminal justice system should appear, even to the most conservative of American observers, to be astonishingly blind and deaf. A good example is the American exclusionary rule, which bars the prosecution from introducing at a trial any evidence obtained illegally by the state. Although this principle is now being substantially narrowed in scope by the Supreme Court, hardly anyone suggests it should be completely abandoned. Moreover, under the US constitutional system, the complex moral questions raised by the effort to change the rule must at least be argued.

To what extent, for example, does exclusion of evidence deter police from making illegal searches? Should it matter whether the police are to blame when the Fourth Amendment has clearly been violated? Even if a magistrate made an honest mistake of law by issuing a warrant, the Constitution may have been breached. Does this mean that there never should have been a search? Are we not all threatened if a court allows unconstitutional procedures because in some cases they uncover evidence of crime? What are the social costs of enforcing an exclusionary rule? How many criminals go free as a result? Should they not go free anyway if they would never have been caught without some violation of the Constitution by the police? Is that not an acceptable price to pay for having constitutional protections for all?

Advertisement

The English courts of appeal have had scarcely anything to say about such questions. The exclusionary issue never reached the highest appellate court, the House of Lords, until 1979, and then, in the Sang case,3 the Law Lords repudiated the notion that the principle could have any part in English law. Lord Scarman, indeed, was so carried away by indignation at the thought that he quoted with some relish the observation of a nineteenth-century judge to the effect that “it matters not how you get [the evidence]; if you steal it even, it would be admissible.”

The absence of any exclusionary rule certainly simplifies English trials by eliminating an entire field of possible motions, hearings, and subsequent grounds of appeal. But how can we admire a system so insensitive that it is unable to perceive that the use of illegally obtained evidence raises serious questions? This blankness is the most striking quality about the arguments of the Law Lords in the Sang case. Their opinions consist of little more than a clerical compilation of scattered observations from earlier court decisions, coupled with unreasoned leaps to abstract views of policy and principle. One finds in these opinions nothing comparable to the intricate and weighty arguments that have been made on both sides of the debate in the United States.

The flaccid quality of English judicial argument concerning criminal procedure, and the general lack of interest in the subject displayed by English legal academics, owe much to the deadening nature of a system that has no Bill of Rights. The English courts fend off every argument based on rights simply by citing the supremacy of executive authority. Unfortunately, this may explain the attraction of the English system to some Americans who are tired of the growing complexity of argument and procedure under the US Constitution. To discharge the obligations of the Bill of Rights, American criminal procedure has been heavily revised during the last thirty years. As constitutional guarantees have more and more been extended to the states, the Supreme Court has had to devise complex federal review procedures to ensure that the states comply with its decisions. This federal pressure has had the effect not only of civilizing and modernizing police practice but of forcing the states to allow convicted criminals a variety of remedies on appeal if state courts are to avoid intervention from the federal courts. Those who complain of complexity often forget that large gains have been made in the protection of rights. Graham’s book misses the hard truth that English trials can be crisp largely because English executive authority is uncurbed; while English concerns for fair criminal procedure, whether in legal analysis or judicial practice, remain trivial. The calm of English courtrooms may resemble that of the desert.

Graham might have made a better case for the superiority of English practices had he written less about jury trials and more about the large number of cases that never get to a jury. While an English jury trial may often be much swifter than an American one, still the costs involved lead the English, as in all the other industrialized nations, to offer alternatives that strongly tempt a defendant to forgo jury trial in favor of some swifter disposition of his case. The classic American technique for achieving this aim is the guilty plea, vigorously encouraged by a substantial discount in the sentence for those who are willing to make the plea.

By now the dangers of such “plea bargaining” should be clear. Reducing the charge in order to make the sentence lighter may have the effect of making the offense appear a trivial one. An American prosecutor can threaten or coerce defendants who will not plea bargain, and in consequence the innocent may plead guilty, without a trial. The questions of fact and of mental state that ought to be fully explored in a serious criminal case are left hanging.

Since most cases must be dealt with fairly quickly, what can be done to improve matters? The most promising reform would be to work out a third method, somewhere between an elaborate jury trial and the hustling of the guilty plea. This would be a simplified form of trial before a judge sitting without a jury, what lawyers call a “bench trial.” Such trials are possible in the United States, but they are restricted by the constitutional requirement of a jury trial for every offense, which carries a possible maximum of at least six months’ imprisonment. Of course the defendant can waive a jury, but many jurisdictions require that both the prosecutor and the court approve of this waiver. Most important, the accused has little incentive to waive a jury since he may have no firm expectation of a reduced sentence if he is found guilty in a bench trial.

Here the English system has advantages. In England many serious offenses, short of the gravest, are “triable either way.” This means that the defendant may elect to have his case tried by the magistrate in the lower criminal court. For the defendant, the strong inducement is that penalties in this court can amount to no more than twelve months in prison. For the state the justification of this practice is that most criminal cases are quickly dealt with, and only the most serious go to jury trial. Compared with typical American procedures this has two great merits. First, the charge is not bargained down, so that the true character of the offense remains visible. Second, the defendant, by choosing the lower court, does not have to plead guilty. He may elect to have a trial before the magistrate. Such trials sometimes last an hour and rarely last more than a day, but they give the opportunity for a genuine defense: indeed 8 percent of all defendants in the Magistrates’ Court, including those charged only with misdemeanors, elect to have a trial rather than plead guilty. By contrast, in many US city courts, fewer than 2 percent of those charged with felonies go to trial.

In this way English procedure offers three choices that make sense both jurisprudentially and economically. Jury trial is elaborate and expensive; a bench trial is quicker, less risky for the defendant, and moderately priced for all; while the inexpensive guilty plea is much less often obtained through a deal that demeans the law. Some American jurisdictions come close to this system4 but the emphasis on plea bargaining as opposed to a jury trial remains the dominant American practice. Revising the system of penalties and sentencing could avoid constitutional difficulties and provide an incentive to elect relatively informal bench trials.

Some English institutional arrangements are thus clearly worth detailed comparative study, but the message of Graham’s book, that we should concentrate on imitating English jury trials, seems strangely perverse. It is true that the increasing emphasis on the Bill of Rights in criminal cases since the 1960s has irritated the public, and some lawyers, by making the criminal process seem interminable. But a drawn-out contest takes place in very few cases and usually only when vital interests or issues are at stake. Seemingly endless motions and appeals may invite derision, yet the system that permits them can be admired for its refusal to close the books when plausible questions of fact or fairness can still be raised. This is dramatically so in cases of capital punishment.

Such labors, in which lawyers stubbornly contend with the awful complexities of trying to do justice, are far preferable to the calm and dispatch that are made possible only by the dark underside of the English system—its expansive ideas of police power, its stunted concepts of the rights of the accused, and the deadening presence of an intellectually impoverished judiciary, supinely deferential to the executive.

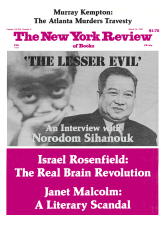

This Issue

March 14, 1985

-

1

The National Crime Survey shows that the percentage of American households affected by serious crime was virtually unchanged between 1975 and 1981.

↩ -

2

Griffin v. California, 380 US 609 [1965].

↩ -

3

Regina v. Sang and Mangan [1979], 2 All England Reports 1222.

↩ -

4

See Stephen J. Schulhofer, Is Plea Bargaining Inevitable?, 97 Harvard Law Review 1037 (1984).

↩