The tenth anniversary of the fall of Saigon has suffused the air with a good deal of nonsense, most of it emanating from persons who never wore a uniform there. The license to assess history is generally a monopoly of civilians who cannot know how it was.

We are being told that the war’s veterans are at last getting the respect denied them until now. Might we not be excused for wondering how much they care? Anyone who withholds and then confers honor on a soldier as though it were some grace within his own keeping has a very small claim to an opinion worth consideration.

The Vietnam veteran may even be fortunate that his country’s gratitude has come so late because, if it had been tendered when it was due, it might by now have turned to scorn. A majority of these men and women have been back in the States fifteen years.

Before World War I was fifteen years gone, those of its veterans who had been enlisted men were such objects of disdain that, by 1932, when a ragged band of them encamped in Washington to agitate for a bonus, the sainted Douglas MacArthur was cheered by most right-thinking observers for burning their huts and chivvying them from the shadow of the Capitol. That memory may explain why so many of those who returned from World War II took care to avoid the American Legion’s embrace and escape the appointed hour when the organized veteran becomes the pariah.

Having mustered sufficient condescension to discover that those who served were virtuous, we are now asked to summon the credulity required for accepting their cause as virtuous. But can we really be expected to think that America’s primary reason for lurching into Vietnam was to preserve its endangered freedom? Wars occasionally sustain freedom and even advance it, but that is almost never their major purpose. Our Civil War was fought to preserve the Union; what we think of, not over-realistically, as the emancipation of the slaves was only an incidental consequence. We went to Vietnam not because we perceived its true interest, but because we misperceived our own and set out to contain the Sino-Soviet alliance.

Defeat has served that purpose as well as victory could have done. There is no Sino-Soviet alliance; Communist China glowers at and has even fought border wars with Communist Vietnam, which has been bloodying Communist Cambodia for six years now. Meanwhile, all the dominoes that were supposed to topple stand as erect as ever.

Vietnam has lost what freedom it had. But the freedom of other nations has never been the first concern of our foreign policy; if it were, we would scarcely be belaboring Nicaragua while according most-favored-nation status to distinctly more repressive governments like those of Romania, Yugoslavia, and China.

To understand that Vietnam was a bad war in no way exempts us from our duty to cherish the men we sent there. To the combat soldier, going through a bad war must be very little different from going through a good one. There is a like proportion of callous and self-serving superiors, an equal number of feckless and hazardous patrols, and just as many of those awful occasions when your weapon is no more useful than a matchstick and you are only a target. But the only reward is no small one, since it is to have known a reality that no civilian ever can.

Bitburg is the tomb of soldiers who died in a cause whose defeat was a blessing to mankind. A wreath would not be unfitting if it were carried there by Americans who had been at the Bulge and endured the best shot the German Army had left. Those Americans would know. The indecency is that Ronald Reagan doesn’t know. Through no fault of his—you go where they send you and stay where they keep you—he has not done the time or taken the beating in war that earns you the right to forgive your enemy and, if you choose, to respect him.

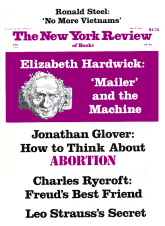

This Issue

May 30, 1985