As I write these lines, perhaps even as you read them, Robert Graves, beyond time and free of its dates and numbers, is dying in Mallorca. He is in the throes of death but not agonizing, for agony implies struggle. Nothing further from struggle and closer to ecstasy than that seated old man surrounded in his immobility by his wife, children, and grandchildren, the youngest on his knee, and a variety of pilgrims from different parts of the world (one of them a Persian, I believe). The tall body continued faithful to its functions, though he did not see or hear or utter a word: his was a soul alone. I thought he could not make us out, but when I said goodbye he shook my hand and kissed María Kodama’s hand. At the garden gate his wife said: “You must come back! This is heaven!” That was in 1981. We went back in 1982. His wife was feeding him with a spoon; everyone was sad and awaited the end. I am aware that these dates are, for him, a single eternal instant.

The reader will not have forgotten The White Goddess; I will recall here the gist of one of Graves’ own poems.

Alexander did not die in Babylon at the age of thirty-two. After a battle he becomes lost and for many nights makes his way through the wilderness. Finally he descries the campfires of a bivouac. Yellow, slant-eyed men take him in, succor him, and finally enlist him in their army. Faithful to his lot as a soldier, he serves in long campaigns across deserts which form part of a geography unknown to him. A day arrives on which the troop is paid off. He recognizes his own profile on a silver coin and says to himself: This is from the medal I had struck to clebrate the victory at Arbela when I was Alexander of Macedon.

This fable deserves to be very ancient.

—translated by Anthony Kerrigan

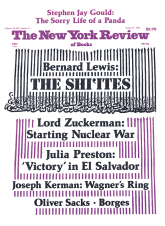

This Issue

August 15, 1985