The Metropolitan Museum’s six-week display of forty Impressionist and early modern paintings from Soviet museums is the first tangible harvest from Ronald Reagan’s colloquies with Mikhail Gorbachev in Geneva last November.

The delights of these fruits are enriched by some piquancies of irony in their flavors. The President and the General Secretary agreed on little except the renewal of cultural exchanges. Now the Soviets have sent us the proudest monuments of their artistic heritage; and they are Gauguin, Cézanne, and Matisse, pricked to prodigies, we are to assume, by the spurs of socialist emulation. Our National Gallery has returned the favor by dispatching a sample of its Cézannes, its Monets, and its Renoirs as testaments to the creativity of capitalist freedom.

Americans and Russians renew their cultural exchange by lending each other French paintings. The dance begins with the partners still at a gingerly distance; in the arts as in weaponry, whatever is native to either superpower remains closely held from the other. But then great and still slightly raw nations are alike in those insecurities that make us prouder of what we bought or stole than of what we did ourselves.

In any case we are as blessed with these Soviet trophies as the citizens of Moscow and Leningrad are with ours. The Tahitian Gauguins seem especially wonderful, because we have so small a stock of Gauguins. Their lights and their forms like dreaming statues strike with the force of the ancient made entirely new, and they touch us almost as much with the intimations of Gauguin’s homesickness for France in the figure of a boy lost and lonely beside a vase of flowers, which is almost an echo of the Met’s own Degas Woman with Chrysanthemums. But if Gauguin stays intractably French, some of the others, Matisse in particular, convey in this setting a curious sense of having been translated into the Russian. That need not surprise us; these paintings were bought by Russians.

Sergei Shchukin and I.A. Morozov were both textile merchants, a useful trade for the eye. Their taste flowered, which from its roots in the icon can be traced in their common preference for flat surfaces and sober, almost Byzantine grandeurs that reach their high point in the great Matisse Harmony in Red. They ceased acquiring shortly before the First World War, and their possessions were confiscated by the Revolution and sequestered in obscurity for a long while before the Soviets thought they could safely be trusted to public view.

From this case, as from so many others, it becomes possible to surmise that the Bolshevik revolution’s purpose was to make it certain that no new or different revolution could ever intrude. The newest of these paintings is seventy-six years old; and our eyes greet them all as variations on a familiar theme. And yet the Soviets seem to think of them even now as departures still pregnant with perils of shock; the catalog they sent along resonates with the cadences of the art appreciation courses of the 1930s with its finger pointings at the symbols of “human despair” in Van Gogh and the appreciation of “man’s role in the universe” in Cézanne.

But for this most conventional of sensibilities, Picasso’s is the untidiest case of all. Piety owes him the tribute reserved for the only left-wing artist on display, and yet the work—1910 work at the latest, mind you—still has powers to unsettle, and all the writers of the catalog can say for two Cubist triumphs, one the Vollard portrait and the other in the key of the Demoiselles d’Avignon, is that “they are two of the finest portraits of the 20th Century.”

The vanguard of the proletariat has again revealed itself as so determinedly rearguard in all other matters as to make us thank the Romanovs for giving those two oppressors of the textile workers their head for a while.

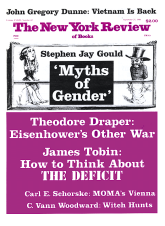

This Issue

September 25, 1986