Gertrude Stein’s apartment on the rue de Fleurus was on the ground floor of an undistinguished building which had none of the grandeur of the seventeenth-century hotel on the rue Christine that she subsequently occupied. From the courtyard, a tiny entrance hall opened onto a large, square, high-ceilinged drawing room, actually a painter’s studio. To the right of the fireplace hung Picasso’s celebrated portrait of Gertrude looking rather hard and stern. To the left was a portrait of Mme. Cézanne, perhaps the most beautiful work of that painter I have seen. The puce-colored walls of the studio were completely covered with unframed canvases. There was one small André Masson and two or three Juan Grises, including a lovely picture of a vase of flowers, the bright-colored flowers having been cut out of a seed catalog and pasted on.

The remaining works were practically all pre-Cubist Picassos of his blue and rose and early Negro periods. There was the little pink girl (whether nude or in long pink underwear I never could make out) standing and holding a basket of flowers; the mysterious woman depicted in profile with a half-closed fan; some early night landscapes in tones of dark Prussian blue; a series of beautiful tiny canvases in his early Negro style, heads and studies for the—in my opinion—quite unsuccessful Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. There were indeed some Cubist works but I do not remember any of his classic Cubist period, those done in straight lines, arcs of circles, and tones of gray, which are so difficult to tell from Braque’s. By the time Picasso arrived at this style, Gertrude, I believe, had stopped collecting.

The furniture was of dark oak and walnut—Louis XIII and Spanish, and there were lots of little prickly baroque-style objects of a vaguely ecclesiastical nature, like polychrome saints and candlesticks. Alice presided over the tea table or occupied herself at an embroidery frame, executing in petit point the backs and seats for a pair of little eighteenth-century chairs after designs Picasso had made for her, all the while telling stories with a mordant and entertaining wit, a wit sharpened by her skill in knowing exactly what to leave out. (Like this from her book, What is Remembered: “Mrs. Luce came to lunch. She was convinced that her husband would be the next president.” That was all, but it probably accounts for the outrageous review the book received in Luce’s magazine Time.) Gertrude’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is made up word for word of the stories I have heard Alice tell. In fact, the autobiography presents an exact rendition of Alice’s conversation, of the rhythm of her speech and of the prose style of her acknowledged works. It is such a brilliant and accurate pastiche that I am unable to believe that Gertrude with all her genius could have composed it and I remain convinced that the book is entirely Alice’s work, and published under Gertrude’s name only because hers was the more famous.

Gertrude would sit on the other side of the room and talk and question. She was short, thickset, and remarkably attractive, her close-cropped gray curls giving her something of the look of a Roman portrait head. She had great forthrightness and a wonderful deep belly laugh. She was not at all the gracious and ingratiating hostess she is usually pictured to be. To the contrary, she was brusque, self-assured, and jolly. Virgil Thomson said that she and he got along like two old Harvard men. When she hit on a phrase or idea that pleased her, she would repeat and repeat it, exactly as she did in her writing. Actually, her writing was not too different from her speech. For example, take her “Conversation as Explanation,” a lecture she delivered at Oxford. If one reads it out loud supplying the punctuation which the text omits, one will have the exact manner and cadence of her conversation.

Alice was indeed ingratiating. She was more of the conventional hostess, but she was not at all the subservient companion she is sometimes pictured as being. She helped in household matters and typed Gertrude’s manuscripts from devotion, not because she was a dependent—her income, I believe, being considerably larger than Gertrude’s.

Gertrude’s remarks were penetrating, laconic, memorable, and full of common sense. Examples: “Young painters do not need criticism. What they need is praise. They know well enough what is wrong with their work. What they don’t know is what is right with it.” And “I am I because my little dog knows me.” The same earthy wit appears in her answers to a questionnaire submitted by the Little Review (May 1929) to the artistic and literary personalities of the quarter—the sort of large, general questions fated to receive pretentious answers: “What was the greatest moment of your life?” “What do you expect of the future?” “What is your attitude toward modern art?” and so on.

Advertisement

According to answers received, the greatest moment of Margaret Anderson’s life was when she met Jane Heap, and Jane Heap’s greatest moment was when she met Margaret Anderson. The Italian futurist painter Enrico Prampolini kidded the questions. His greatest moment was “one of simultaneous creation, artistic and sexual. At the moment of possessing a woman I loved to madness, I drew on her back the design for my greatest masterpiece.” In what, I wonder.

Gertrude’s answers were straightforward and somewhat wry. Her greatest moment was “birthday.” To “What do you expect of the future?” she wrote, “More of the same.” And to “What is your attitude toward modern art?” she answered: “I like to look at it.”

She did indeed, both to look and to buy. At least she liked to buy in the earlier days when the Steins, Michael and his wife Sarah, Leo and Gertrude, turned up in Paris fresh from San Francisco. This was in 1903 when Mike, the eldest and the businessman, had sold a railroad spur they had inherited and made enough money out of the deal for them all to retire, made them rich enough also to be able to invest in the works of the new, young painters. Mike specialized in Matisse. Gertrude and Leo went straight to Picasso. (There is a story of how Leo locked the terrified painter in a room and refused to let him out until he had explained Cubism.)

Gertrude and Leo must have formed a very united couple, and I believe that it was Leo’s eye rather than Gertrude’s that guided their brilliant early foraging. Alice arrived from San Francisco in 1906 and moved in with them. They all lived together until 1912 when Leo moved out. The break must have been complete. As far as I know, Gertrude never saw him again. At any rate, I myself never heard either Gertrude or Alice speak his name. After his departure, Gertrude stopped buying pictures. Her explanation was that she had acquired a Ford and that there was not enough money both to run a car and to collect art. Whatever the reason, after her separation from Leo, she did not interest herself seriously in any painter—though she flirted with a great many of them—until in the late Thirties she encountered Sir Francis Rose and, according to rumor, purchased some four hundred of his works.

Francis was a well-to-do and vastly irresponsible young Englishman, quite pleasant looking but with a rather childish speech defect of spitting. He had been brought up by his mother and uncle in Villefranche-sur-Mer—until 1928 the home port of our Mediterranean fleet and a fashionable resort for that very reason—and was a protégé of Bérard and Cocteau from whom he had derived whatever training in painting and drawing he received. Nobody took his painting seriously then and no one takes it seriously now. Indeed, in the exhibition held in 1971 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York of pictures that had passed through the hands of the Stein family, not one of Gertrude’s four hundred Francis Roses was shown. To explain Gertrude’s faith in him, I must suppose that she was less interested in painting than in personality; that she was not looking for more pictures but for another great man, another Picasso marked with genius, and the tumultuous excesses of Sir Francis’s life and his undisciplined facility convinced her that she had found one. Alice’s several published cookbooks contain illustrations by Francis which well exhibit his amateurish and untrained vigor.

In the fall of 1929 when I first met her she had been looking over the new young painters, who at the time were Christian Bérard, Kristians Tonny, and Pavel Tchelitchew, and had decided against them all. Bérard was the first actually French painter of the School of Paris since Braque, all the others being foreigners, and he had already acquired a body of enthusiastic admirers. Tonny was a handsome young Dutchman, a contemporary Brueghel, and his depictions of a fantastic insect world executed in a linear form of monotype were much admired. Gertrude owned an oil portrait he had done of her dog Basket and a painted fire screen. Tchelitchew was a White Russian of aristocratic family, a rival to Bérard, and a draughtsman every bit as good as Ingres. Gertrude kept him around for some time without making any serious commitment and ended by turning him over to the Sitwells who took him to London and prepared his English success.

Advertisement

Gertrude asked Virgil if he had heard of any other interesting new painters. This was in the spring of 1930. He suggested Léonid’s younger brother, Eugène (Genia for short) Berman, who was then doing dark, romantic landscapes in something of an Italian seventeenth-century manner, and nocturnal quay-side scenes with sleeping beggars and mysterious pyramids of piled-up merchandise. Gertrude and Alice went to his studio and were delighted with the work. They at once bought a couple of pictures, and since they were leaving the next day for their summer home near Belley, they invited Genia to visit them there. Genia arrived and when he came down to breakfast a few mornings later he was brusquely told the time the next train left for Paris and dismissed. Gertrude explained later that he had behaved in an unpardonable manner, that he had become sexually excited at the sight of their maid and did not take the trouble to conceal it. Alice, in her published letters, gives a somewhat different account; that one night they rang for the maid who did not answer the bell, and when they went to her room to see why, they found Genia closeted with her.

This is a strange and unlikely story, like a misapprehension contrived to further the plot of a French farce, or more likely an excuse to justify a sudden ungovernable dislike. In Paris at that time, the details of everybody’s sex life were public property. The source of a friend’s income might remain obscure but not what he did in bed or whom he did it with. Genia was known to have passionate sentimental attachments (like his later unhappy union with the actress Ona Munsen). But he was judged by all, even by his devoted brother Léonid, to have no active sex life whatever. Anyway, Gertrude bought no more of his pictures.

My own painting she never paid the compliment of asking about, and she was quite right not to do so. I was still learning to paint and quite unready to be discovered. My peculiar literary gifts, which we employed in staging the two Stein-Thomson operas, Four Saints and The Mother of Us All, she took very seriously indeed, actually saying somewhere in print that I was the only one who knew how to put her plays on the stage but, unfortunately, I preferred to spend my time painting. I could have answered that putting her plays on the stage was scarcely a full-time job.

When I went back to France in 1953, after the war and after Gertrude’s death, Alice and I became the best of friends. But in these earlier years my relations with Gertrude and Alice were not too easy, principally, I believe, because it was through Virgil that I came to know them. On my first visit to Paris four years before, I had been provided with a letter to Gertrude from her old friends, the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead and his beautiful wife. But I was too timid, and really not interested enough, to present it. This I have since regretted. Had I gone to see them then, I would probably have been accepted on my own merits. Coming as Virgil’s friend, I was only the less interesting member of a pair. Consequently, I never developed any real intimacy with Gertrude. (As proof of this, my name does not occur in any of her poems.)

In fact, she rather intimidated me. Gertrude had a special way of dealing with couples. She would take over the artist or writer, leaving Alice to deal with the friend or wife. Alice would eventually get tired of the friend or wife, and if she got tired enough she would enlist Gertrude’s help and try to make the pair break up. There is a typical example of this in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas where Alice begins taking French lessons from Fernande, at that time Picasso’s mistress, so that Fernande would have money enough to leave him. At one point, I believe, Alice attempted to separate Virgil and me. One evening when Virgil was alone with them, his relations with me were vigorously attacked. Virgil stood up for me and the matter was not mentioned again.

Alice, in her quiet way, was very possessive. People that Gertrude became too fond of were liable suddenly to be dismissed, never to appear again. Gertrude would unexpectedly quarrel with the very people she had been the most intimate with, like her brother Leo, or Mabel Dodge, or Bravig Imbs, or Hemingway, or the poet Georges Hugnet, or Virgil himself (though Virgil and she resumed their friendship after the production of Four Saints). And I have always thought it was Alice who provoked the quarrels, though Gertrude herself was not averse to a change of scenery. “A Jew,” she once said, “is a ghetto surrounded by Christians. What we need this year are some new Christians.” And since Gertrude’s was the best-known English-French literary salon in Paris, there were always enough new Christians turning up.

As for the opera Four Saints in Three Acts, the whole business of its composition was somewhat peculiar. Virgil and Gertrude had settled on sixteenth-century Spanish saints for their subject, the saintly life being used, I suppose, as a metaphor for the devoted life of the artist we all considered ourselves to be leading. The text for the opera, when delivered, turned out to be just as obscure, and as full of repetitions and undecipherable private references as Gertrude’s poetry always is. There were no indications of what was to be taken as stage directions and what was to be sung. Most of the speeches were unassigned. On two points, however, Gertrude was clear. The aria “Pigeons on the Grass, Alas,” which occurs in the third act, was to be a vision of the Holy Ghost, and the long passage beginning “Dead, said, wed, led” was to be a religious procession such as is performed in Seville during Holy Week. Virgil, on his side, divided the role of Saint Teresa into two, there being too much of it for one singer alone. This also enabled her to sing duets with herself. He also introduced two characters, a Compère and a Commère, not saints at all but elegant laity, who were to act as end men in a minstrel show to introduce the saints and to comment on the action.

Virgil’s way of writing the music was also a little peculiar. He would sing the text over to himself and when a passage came out always the same, he would write it down. At the end he found that he had set the whole text to music—stage directions, names of characters, as well as the numbers assigned to the scene and act divisions. So that when we came to think about staging the opera, all there was to work with was a dense mass of music which had absorbed everything else. My way to deal with this was to get Virgil to sit at the piano and sing the opera through. I would listen and try to imagine what was going on on the stage. It all came together very easily.

My scenario began with a sort of choral introduction which ended with the Commère and Compère introducing the saints by name. The first act that follows is a sort of Sunday school entertainment in which the two Saint Teresas act out on a small stage the principal events of their—or rather her—life. The second act is a garden party, which the Commère and Compère attend, seated together in an opera box at one side of the stage. The saints play various games like “London Bridge” and “Drop the Handkerchief.” There is a ballet of angels, a love scene between the Commère and Compère, and a toast by the saints to the happy couple. Saint Ignatius arrives with a telescope through which he shows them a vision of the Holy City. Saint Teresa wants to keep the telescope. When it is explained that she cannot have it, she accepts the refusal gracefully and the act is over.

Act III takes place on a seashore where Saint Ignatius is training his disciples. The Holy Ghost appears to him and he sings about it and calls his distracted disciples to order with a sermon. There is a ballet of Spanish sailors and their girls. The saints form a propitiatory procession which slowly marches off the stage. The Commère and Compère come out in front of the curtain to discuss and introduce a fourth act. The curtain lifts to reveal the saints now in heaven and singing about their life on earth. This may sound rather silly, but when the opera was finally performed in Hartford four years later, my scenario turned out to be an ideal framework, and I am now convinced that the opera cannot be properly given without it. Except for Gertrude’s two suggestions, the stage action was made up without her cooperation. In fact, by the time the scenario was set, Gertrude had quarreled with Virgil and they were no longer speaking.

The break between them came in the wake of a quarrel between Gertrude and the French poet Georges Hugnet. Georges was a Surrealist, even, I believe, an official member of the group. A tough, handsome, and rather truculent young man, he was a great friend of Virgil’s, in fact Virgil had set a number of his poems to music. Georges had recently completed a long series of poems about his childhood entitled “Enfances” which Gertrude—who at this time was seeing a great deal of him—found so admirable that she undertook to translate it into English. The two texts, Gertrude’s translation and Georges’s original, made up a remarkable pair, inasmuch as the obscurities of one acted to clarify the obscurities of the other. They decided to publish the two works under the title “Enfances, Poems by Georges Hugnet, Followed by an English Translation by Gertrude Stein,” this being, of course, in French and not in the English I have given.

The title, however, did not long satisfy Gertrude. Her part of the work, she began to consider, was much too good to be dismissed as a mere translation. In fact, it was an important independent work, and the title had to be revised to read: “Enfances, Poèmes de Georges Hugnet et Gertrude Stein.” Even more, since Gertrude was a woman, it was only natural that her name should be given precedence and be cited first. Georges refused to accept the change and they fought bitterly over it. All the Quarter took sides, while Picasso, who loved a good literary quarrel, egged everybody on.

In the meantime Christmas was approaching and Gertrude and Alice invited Virgil and me to pass Christmas Eve—this was 1930—with them in their flat. We were four. We exchanged gifts, were given a ceremonial dinner, and passed a very pleasant evening. The subject of Hugnet came up, and Virgil, who did not at all approve of the behavior of either party, proposed a compromise, which he had already persuaded Hugnet to accept—something about adding after each name the date of the work’s composition. Gertrude agreed to the compromise, apparently so did Alice, and we left with the impression of having spent with them a pleasant and friendly Christmas Eve.

Virgil then came down with his usual winter bronchitis and stayed at home in bed, his throat wrapped in flannel. One morning, a week or ten days after Christmas, he received in the mail a small stamped and addressed envelope containing a calling card which read: “Miss Gertrude Stein” (this engraved) and underneath in Gertrude’s spidery handwriting, “Declines further acquaintance with Mr. Virgil Thomson.” That was all. Virgil was too hurt to answer or protest, and they did not see each other or speak again until the fall of 1934 when Four Saints was revived in Chicago and Alice and Gertrude came there to see it. The whole affair, aimless, silly, and wounding, I can explain only as another example of Alice’s jealousy working on Gertrude’s literary vanity, here acting to persuade her that Virgil had gone over to the enemy’s camp.

Despite all this, the two “Enfances” nevertheless appeared together, on facing pages in Sherry Mangan’s quarterly Pagany, Winter 1931, under the title Gertrude herself must have devised: “Enfances—Georges Hugnet” and “Poem Pritten on Pfances of George Hugnet—Gertrude Stein.” Her translation was later published by itself, entitled, appropriately enough, Before the Flowers of Friendship Faded Friendship Faded.

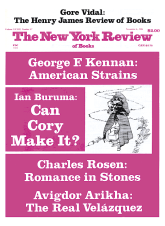

This Issue

November 6, 1986