1.

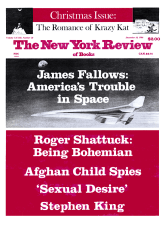

George Herriman was thirty-three when he solved the problem of evil. This was in 1913, when he introduced Ignatz the mouse into his comic strip, Krazy Kat. Because Krazy Kat includes Ignatz, the crazed brick-throwing rodent, we don’t normally think of Herriman’s Coconino County as an imaginary Eden, a highly personal vision of a perfectly harmonious place. But in a subtle and surprising way, Herriman’s world isn’t just Edenic, but really of all imaginary Edens the most like the original: it includes a serpent. The essential triangle and repeated action of Krazy Kat, the perpetual pavane-with-brick among Krazy, Ignatz, and Offissa Pupp, is more or less what would have happened had the Fall never taken place, and Adam and Eve (poetically represented in their presexual state as a single being, the sexually ambivalent Krazy), the Serpent (Ignatz), and the Archangel Michael (Offissa Pupp) been left alone in Eden forever.

By including Ignatz in his Eden, Herriman suggests why God allowed the serpent in Paradise—he wanted to create a world in which evil existed as a source of necessary energy but didn’t cause suffering, and then somehow He let it all get out of hand. Herriman shows us what would have happened had we all been luckier. Ignatz, who came out of Herriman’s pen as a malignant little tangle of barbed wire, with the gaunt form and gimlet eyes of a sewer rat, isn’t mischievous, like his sanitized shadow, Mickey Mouse—he’s wicked. No destructive or aggressive impulse is foreign to him, and his obsessive anger finds its everyday outlet in his desire to throw bricks at the dreamy and innocent Krazy, a divine idiot who chooses to see in Ignatz’s nastiness an expression of love.

Yet what makes this enchanted landscape, this vast, numinous desert, with its moon like a deflated volleyball and its cacti of crumpled tinfoil, so Edenic is not just that Ignatz has no power to harm, but that each brick is transformed in midair into a bouquet. Herriman’s favorite representation of the moment immediately after Krazy has been hit by Ignatz’s brick has the eloquent symmetry of a photograph of a subatomic collision: while the brick bounces harmlessly off Krazy’s head in one direction, at precisely the same moment a little heart—symbolic of Krazy’s love for the mouse and gratitude for his attentions—appears and spirals off in the opposite direction, a complementary particle produced by the balanced moral physics of Herriman’s Eden.

If Ignatz’s bricks, which bless rather than bean, represent evil in its prefallen state, as pure and delightful energy, then Offissa Pupp, like the Archangel at a time when there could be no transgressions to punish, represents Law as pure form. We understand that Offissa Pupp, who ends almost every strip by throwing Ignatz in a little one-mouse jail, in some sense has no need to enforce the law: Krazy likes being hit by bricks, Ignatz likes throwing them; the thing is perfectly arranged. Offissa Pupp’s obligation is to the abstract concept of justice as a pleasing formal arrangement rather than to the necessary role of law in the fallen world, as a way of maintaining order: he puts Ignatz in jail for aesthetic reasons. Offissa Pupp loves Krazy for his innocence, but his allegiance to the web of order prevents him from ever declaring his feelings, or attempting to alter Krazy’s love for Ignatz. To do so would be to let passion dictate to design, and that is not possible in Eden.

But imaginary Edens, dreams of the first domino before it was nudged, by some principle of inversion can only be achieved in art after a very long row of dominoes has fallen. In order to understand how Krazy Kat happened, we have to understand how and why several other things happened first: how caricature and cartoon came to be emancipated from the tradition of political satire, and how the sublime landscape was liberated from the tradition of high seriousness. And we should understand how this liberating contribution to our visual language was achieved by an almost forgotten generation of turn-of-the-century American newspaper artists. In less than thirty years these artists, daily drudges of the Hearsts and Pulitzers, transformed caricature into cartoon and cartoon into the comic strip, and thereby constructed an entirely new idiom that would allow the most remarkable of their number, Herriman, to create, in Coconino County, a comic pastoral as timeless as Blandings Castle.

Today, more than at any other time since its creation, Herriman’s achievement seems likely to be appropriately valued. Within the last three years there have been two shows of Herriman’s original drawings at a prominent gallery in New York; a whole subschool of East Village painting, none of it much good or really Herrimanian, is called Krazy Kat Painting; and Patrick McDonnell, Karen O’Connell, and Georgia Riley de Havenon have produced an illustrated monograph on Herriman and Krazy, one of the most carefully and seriously produced volumes ever devoted to a comic-strip artist. But the sudden efflorescence of Krazy Katiana reminds us mostly how sporadic the critical tradition remains in the study of cartoon and comic strips. That tradition belongs largely to the history of endorsement rather than of interpretation.

Advertisement

Herriman has never lacked for admirers; from the appearance of Krazy Kat before the First World War, it’s been widely recognized that Herriman had achieved something not only entrancing on its own terms but also uncannily modern, bearing deep affinities to the spirit and form of crucial styles in vanguard art. Anyone who writes about Herriman points out that he was admired by important painters. But even the history of his highbrow endorsements has the vague quality of a folk rather than a scholarly tradition: the authors of the new volume claim De Kooning and Cummings (Cummings’s introduction to one of Herriman’s collections is still worth reading; it was reprinted in 1969, and isn’t hard to find) and that seems established, but just last month a generally knowledgeable comic-strip historian, writing in one of the aficionados’ magazines, blithely claimed Picasso and Gertrude Stein for Herriman, too. (You get the feeling that among the hard-core comic-strip aficionados, Picasso and Stein and Cummings and De Kooning are assumed to be connected like prisoners in a chain gang; nab any one and you get them all.)

The most emphatic effort to jump-start a tradition of serious Krazy Kat “kriticism,” as Herriman called it, by sending a cable over from high culture, remains Gilbert Seldes’s essay of 1924 from his book The Seven Lively Arts. Seldes’s book remains a pioneering attempt to take popular culture seriously, and his choices, a half century later, seem amazingly prescient—Herriman and Chaplin in particular. But the authors of the new book use his essay, uncritically, as a preface, implying that it’s the last rather than the very first word, and that won’t do. For all his sympathetic description and skill, Seldes still chose to credit Herriman with doing things that Herriman just doesn’t do. Seldes sees Herriman as a comic-strip cognate for certain artists—Dickens, Rousseau, Chaplin—whose abilities are very different from Herriman’s. The gift of Dickens or Chaplin for verbal or pantomime caricature doesn’t have a lot to do with Herriman, who was, in fact, a very mediocre caricaturist; Rousseau’s horror vacui and obsessive attention to detail also have nothing to do with Herriman’s austere, emptied-out landscapes, and Herriman anyway was in no sense a naïf.

In some ways Seldes’s essay has done more harm than good, since it has given Herriman the kind of place among comic-strip artists that Chaplin once held among film buffs or Ellington among a certain kind of jazz aficionado—their apparent atypicality made them acceptable. Seldes’s essay on Herriman suffers from the same kind of dislocation of sensibility, the same discrepancy between what we sense and what we say, that more often overcomes well-meaning critics writing on Ellington: even as the toe is tapping to “Perdido,” the tongue can’t help but say something about Delius. (This isn’t to slight Seldes’s prescience: the political commentator who saw, in 1952, that the host of GE Theater was the man to watch doesn’t lose points just because he thought his man would run for the Senate first.)

What McDonnell, O’Connell, and De Havenon have done is to leave the interpretative questions largely to one side and concentrate instead on getting the facts straight about who Herriman was and exactly what he did. Anyone who has ever tried to find out something about the lives and works of turn-of-the-century cartoonists can’t help but be impressed by the authors’ achievement as biographers; the lives of twentieth-century cartoonists can sometimes seem more cloaked and hidden than those of fifteenth-century Italian artists. But choosing to write a biographical study of George Herriman is a bit like choosing to write a biographical study of Fra Angelico: once your hero takes his vows and enters the monastery, there’s not a lot to say. Herriman’s life was a kind of funny-page fulfillment of Flaubert’s dream of total absorption in the oeuvre. In this sense only three things ever happened to him: he was born (not a joke, as we’ll see), he joined the staff of the New York Evening Journal in 1910, and sometime before the First World War he discovered Monument Valley in Arizona. The first two events gave him a style; the last, a subject.

Advertisement

2.

George Herriman was born in New Orleans in 1880, and McDonnell, O’Connell, and De Havenon have discovered that he is listed on his birth certificate as a Creole, which in New Orleans at the time was apparently a fancy way of saying black. This is really news—no one mentioned it during his lifetime, certainly not the artist himself. Herriman’s family moved to California when he was a little boy, probably to escape the South, but even so it’s hard to see how he could have been left unaffected by the ambiguities and apparent masquerades of hiscircumstances (which Herriman perpetuated, telling different people that he was Greek, French, or even Navajo).

When George Herriman entered the newsroom of the New York Evening Journal in 1910 as a young staff artist, he was walking into the Bateau Lavoir of the American comic strip. The staff of the Journal included almost everyone of consequence who had been working in the new art form: James Swinnerton, who along with Outcault, had invented the new form only twenty years before; Winsor McCay, at that time drawing Little Nemo in Slumberland as a Sunday page; Rudolph Dirks, who drew The Katzenjammer Kids; Cliff Sterret (Polly and Her Pals); and the sports cartoonist Tad (whom Jimmy Cannon, thirty years later, would still remember as the most gifted of all). In the previous twenty years, these artists had moved the tradition of caricature decisively away from political satire, and thus away from the practice of physiognomic distortion and expression that had defined the form from its first invention in the circle of the Carracci in Bologna, three hundred years before. In its place they had created a new kind of comic drawing that depended far more on design and the creation of durable characters than it did on the epigrammatic reduction of faces.

The work of Winsor McCay shows best what the new style could and couldn’t do. Little Nemo is a strip of almost rococo delicacy of drawing; McCay had made his characters much smaller in relation to their surroundings than any previous cartoonist, and had thus won new space in the comic-strip frame for landscape and architecture. Little Nemo travels every night through a dream cityscape, a child’s poetic transcription of the emerging New York of skyscrapers and elevated trains; McCay was able to use the new space he had won in order to present a beatific vision of New York as a dream world of technology and the machine, the same vision Rube Goldberg would soon present as a nightmare.

But McCay’s work demonstrates that there were risks as well as benefits in the new freedom. His work is charming rather than funny, moving not toward a new kind of humor but away from humor altogether. By 1910 the comic strip, even in the hands of someone as gifted as McCay, was moving tepidly toward other kinds of popular illustration; it had left the narrow realm of faces only to risk its soul.

Herriman quickly absorbed the elements of this most advanced of comic-strip styles, and then purified it. The house style of the Journal, which valued character and line over caricature, suited Herriman perfectly, since he was not a skillful caricaturist. The first daily strip that he drew at the Journal was very different from the lighthearted, curvilinear strips that had won him the job in the first place. His first comic strip for the Journal, The Family Upstairs, tells of the monomaniacal attempts of a New York family, the Dingbats, to somehow obtain one glimpse, however brief and however dearly bought, of their bohemian upstairs neighbors, whose constant invisibility has convinced the Dingbats that, right there, over their heads, there exists some mad, enormous world of dangerous licentiousness and wonderful possibility.

The attempt to get one small, fleeting look at the Family Upstairs becomes the Dingbat family grail, involving in the attempt policemen, private detectives, Rube Goldberg contraptions, etc. From McCay and the other Journal artists Herriman borrows the new scale—the Dingbats have become much smaller in relation to their surroundings than the characters in any previous work by Herriman—but instead of filling in the empty backgrounds with McCay’s whimsical clutter, Herriman purposefully lets it alone. Herriman obviously wants us to see the barren material world of the Dingbats as a spur and foil to their wonderfully paranoid interior life, and so they move in a spare, empty world of white walls and geometric moldings, bare hanging bulbs, and closed, gridded windows. (Thurber would arrive at a similar telegraphic vision of the desert of the middle-class apartment several years later, by much more naive and empirical means.) It is a poetic reduction of the right-angled, carpentered world of a middle-class apartment, c. 1920 (much exaggerated, surely—no apartment before the Bauhaus could have been as empty as the Dingbats’), and it brought to comic art a new purity and austerity of form.

Herriman, from then on, had as clear a sense as any artist alive of what big unaided areas of black and white can do. (It’s too bad that the publishers of the new collection couldn’t, or didn’t, reproduce Herriman’s work in its original size, that is, the size of a full page in the old Journal-American, since Herriman’s control of big areas is much harder to appreciate within the confines of the much smaller proportions of the new collection.) Soon Herriman added, running along the baseboards underneath the Dingbats, a fuguelike undervoice to the strip involving the adventures of a neurotically inverted cat and mouse—the rodent chases the feline—whose slapstick echoes and mimics the Dingbats’ frustrations. Before long, especially after the mouse started throwing bricks at the cat, they had become as interesting as their human neighbors, and Herriman decided to make a strip for them alone.

Give These Animals a Home. But where? In 1902, long before Herriman had created either the Dingbats or Krazy Kat, he had been interviewed by The Bookman (interesting in itself for what it suggests about the position of a cartoonist in the period) on the pains and joys of professional cartooning. Herriman’s complaint about the cartoonist’s lot was very peculiar, one that I very much doubt any cartoonist before Herriman—not Daumier or Nast, much less Tad or Sterret—would have thought to offer. The cartoonist, Herriman explained, was handicapped because his given style wouldn’t allow him to respond to nature:

What does he [the cartoonist] know of the inspiration to be obtained from blue, azure, and turquoise skies…. Take the clouds and skies of which I speak, blend them with the green grass and gamboling lambs, and a few trees, a few redroofed barns, little hamlets in the distance, a lake, a creek, a rustic bridge, a nestling home amid clinging vines, and lots and lots of other things so dear to an artist’s heart, place them in full view of the inspired one and see the light of imagination fire him. They never will. His mind and soul have lost that delicate sense of the poetic and artistic, which one would naturally think were indigenous and he will turn away with a sigh, sit down at his desk and continue to worry out idiotcies for the edification of an inartistic majority.

The language is clichéd—though in that special, self-conscious way that would later flower so beautifully in the deliberately stilted dialogue of Krazy and Ignatz (for Herriman, as for S.J. Perelman, English clichés had something of the awful fascination of midget wrestlers)—but the feeling’s real enough. It must have been an unhappiness that could only have increased over the next ten years as his work became, with the Dingbats, increasingly urban.

Then, sometime around 1910, Herriman visited the Monument Valley of Arizona—the sublime western landscape of natural skyscrapers and endless horizons that, many years later, John Ford was (quite ahistorically) to make the inevitable setting for the movie western. For Herriman, it was like Turner discovering Venice. The Monument Valley was a landscape which, in its natural geometry, its austere expanses poetically punctuated by irregular and whimsical out-croppings and towers, seemed perfectly made for the artist’s newly evolved style, God’s answer to the Dingbats’ apartment. The reductive urban slang of right angles and austere space that Herriman had invented for The Family Upstairs could be perfectly reimagined for this odd, lunar landscape, where nature appears to have been shaped not by the slow, smoothing processes of time but by the acts of an immense, eccentric sculptor impatiently wielding a chisel and drill. In the long expanse of mesa, the lunar crags, and neolithic needles (as well as in the related art of the indigenous Zuni and Hopi, whose geometric forms seemed to him a similar stylization of the surrounding landscape) Herriman found a world that spoke immediately to his imagination. He moved the cat and mouse out of the Dingbats’ urban wasteland and into the enchanted mesa of the Monument Valley, and began the strip we know as Krazy Kat.

3.

There is probably no other case in the history of cartoon or caricature where an artist had a romantic experience of nature—comparable in its force and specificity to Constable in the Stour Valley, or Turner at Venice—and had then found a way to make this vision part of his work. (Edward Lear, of course, responded powerfully to nature, but, typically, he kept his landscape and his nonsense entirely separate.)

Saul Steinberg, who has thought deeply about Herriman’s work, also points out that the play between indoors and outdoors in Krazy Kat contributes crucially to the uncanny sense Krazy gives of summing up a whole period in American life: more than any other work, Krazy Kat clarifies the way in which natural and man-made forms are bound together in American art deco. It’s certainly true, as Steinberg suggests, that the terraced and set-back needles of Monument Valley were a formal current that nourished the romantic American skyscraper: block up the windows of the RCA building and plonk it into the middle of Arizona, and it wouldn’t look a bit out of place. Herriman understood this in some intuitive sense, and his drawings, with their constant ambiguity about what in his metamorphosing backgrounds is natural and what man-made, perhaps seem so evocative to us because they seem to mediate so perfectly between Rockefeller Center and Monument Valley, in something like the same way (though obviously on a much smaller scale) that the fog and steam in Turner evokes at once temporal and eternal England, both the Celtic mists and the poetry of the Industrial Revolution.

This tension between city and country, between the urban rhythm and the Arcadian subject, isn’t just implicit in the visual design of Krazy Kat, it also soon became part of its explicit drama. If the drama of Krazy Kat is elemental, its language is purposefully overelaborate and urban. This is a crucial part of the joke in Krazy Kat, in the same way that part of the joke in Wodehouse is that Bertie Wooster’s language is far too literary for his predicament. Creatures know more than they need to, and as a consequence forms of language that in the city, the fallen world, are devoted to serious disputes can be treated as a kind of game. Like Rosalind and Jaques, the inhabitants of Coconino County are happy exiles from the city, their concerns and conversations those of the educated city dwellers they originally were; you can take the Kat out of the Dingbat apartment but you can’t take the Dingbat apartment but you can’t take the Dingbat apartment out of the Kat. With his Keystone Cop’s helmet and double-breasted jacket, Offissa Pupp is clearly drawn not as a western sheriff but as a Gotham cop on the beat, transplanted into an alien milieu of the West in a reversal of the sitcom cliché.

The conversations of Krazy and Ignatz also become philosophical eclogues, on occasion bluer about the futility of language than Wittgenstein’s notebook: “Ignatz, why is lenguage?” “Language is that we may understand one another.” “Is that so?” “Yes, that’s so.” “You understand a Finn or a Leplender or A Osh kosher?” “No.” “Then I would say, Lenguage is that we may misunderstand each other.” Philosophical dispute, in the enchanted world, becomes a form of play. (Good as Herriman’s dialogue is, and perfectly suited as it is to the dramatic needs of his little bestiary, it still is considerably more derivative, from Lardner and Don Marquis particularly, than his drawing. His verbal gifts, wonderful and original as they are, aren’t quite as great as his gifts as a draftsman. If Krazy Kat were written in Linear B, we’d still get its essential spirit from the drawings alone—walk into a gallery full of Herrimans and, even before you can begin to read, the force and spirit of the designs hit you as though you’d been beaned with a brick.)

The landscape of Krazy Kat, this intersection of indoor angles and outdoor spaces, doesn’t just look unmistakably Herrimanian: in its dreamlike mutability and strangeness it looks surrealist. This is an apparent affinity that sooner or later occurs to everyone who cares for Herriman, an affinity that raises basic questions about the relationship of popular culture to modern art. The authors of the new volume seem to feel that they have disposed of the issue by pointing out that what often seem like whimsical inventions in the landscape of Krazy Kat are in fact poetic reductions of real scenery:

The Italian author Umberto Eco writes of ‘certain surrealistic inventions, especially in the improbable lunar landscapes.’ Herriman’s Coconino County may seem irrational and improbable, but most of the backgrounds are realistic depictions of the rocky outcroppings and vegetation of the valley.

But that’s not the point. When Eco or anyone else refers to surreal elements in Krazy Kat he doesn’t mean that the landscape looks strange. They mean that the Herriman seems to respond, with uncanny coincidence of imagination, to the same mix of places, myths, ambitions, and goals that moved surrealism proper: the same fascination with aboriginal art, the same love of anthropomorphic bestiaries, the same feeling for eloquent illogic, the same love for desert landscapes.

Max Ernst is the most striking immediate parallel. Ernst enunciated as a vanguard program in 1921 precisely the same program of action that Herriman had, ten years before, already put into practice as a comic-strip artist: the same powerful response to the landscape of the American desert, the same fascination with the culture of its natives, and the same deep belief that this landscape was the Epidaurus of the imagination, the perfect natural theater on which to project a timeless psychodrama acted out, as a scholar of Ernst’s art puts it, in language that could apply equally well to Herriman, by a “bizarre, personal ménage of insects, fish, animals and fantastic hybrids that constitute his personal bestiary.”

But Herriman and Ernst don’t have much in common visually. Herriman planted his flag in this territory of the imagination while Ernst was still poring over his maps and putting in supplies. Bluntly, Herriman is a much more skillful and original draftsman than Ernst, whose drawings of imaginary beasts in the desert of the Southwest, when he finally arrived to produce them in the 1940s, seem ham-handed compared with Herriman’s.

A more striking visual parallel that unites Krazy Kat and European surrealism, the surrealism of the museums and the surrealism of the funny page, can be found in Miró’s paintings of the mid-1920s. If we compare Miró’s Carnival of the Harlequin or Dog Barking at the Moon with typical panels from Krazy Kat—almost any of the concluding nocturnes from the Sunday pages of the 1930s, but also Krazy watching Ignatz ascend on the end of a balloon (April 30, 1916) or Krazy watching the cheese-moon rise (August 19, 1917)—we sense a real, positive affinity in a shared system of form: an imaginary anthropomorphic bestiary, drawn with dancing grace and wiry life, poetically juxtaposed against an infinite and numinous landscape. Like Herriman’s, Miró’s fantastic bestiary resides in a deep, limitless space, not the uneasy void of De Chirico or Tanguy, or the barren plain of Dali, but rather an expanse that suggests limitless possibility and an oceanic stillness. Like Herriman’s, Miró’s work is structured by the play between terse indoor and expansive outdoor form: in the Carnival the insects’ ball takes place in a stripped architectural space—the insects, as Miró himself said, have crawled out of the cracks in the plaster—that is also an analog and starting point for the endless imaginary dream space of the Dog. Even details match: the squiggled needle glimpsed through the window in the Carnival could have come right out of a Krazy page, while Miró’s soaring ladders have their counterpart in Herriman’s great stone fingers. Both devices serve common formal and symbolic purposes: they provide a strong gravity-defying verticality to counter-act the hold of the horizon, and they also suggest an enchanted universe where heaven and earth still adjoin. Even Miró’s most succinct statement about his artistic ends and means could have been put in Herriman’s mouth without a missed beat: “In my pictures, there are tiny forms in vast empty spaces. Empty space, empty horizons, empty plains, everything that is stripped has always impressed me.”

What has the Kat staring at the stars to do with Miró’s dog barking at the moon? While it’s unlikely that Miró and Herriman never saw each other’s work, mere casual contact obviously can’t account for the resemblance. And it’s snobbish to treat Krazy Kat as a kind of “found-art” object, which resembles a Miró in the way that a beach pebble may resemble a Henry Moore—because the work of art instructs us to see particular form in mere accident. Popular imagery, and caricature and cartoon in particular, have had from the beginning of modernism a large part in the evolution of vanguard style, from Courbet’s adaptation of compositional ideas borrowed from the popular woodcut, through Picasso’s daring use of caricatural form in his Cubist portraits, on through the more obvious appropriations and adaptations of popular imagery in recent art. Perhaps Miró bears the same relation to the caricature of landscape and animal—to the comic strip’s sources in the nineteenth-century tradition of fantastic illustration—that Picasso bears to the caricature of faces. Surrealism, after all, has always had a suspiciously large number of precursors and parallels in popular art and illustration, from Tenniel and Grandville to, allegedly, Herriman.

As Gombrich has shown so often, even the most imaginative artist can only work with an idiom, a tradition, that supplies the raw material he must have to represent even his most personal vision. For Miró, as for the Surrealists generally, that raw material came largely from popular imagery. What Herriman and Miró both did was not so much to invent a style as to take already existing idioms, mostly popular and peripheral—the anthropomorphic bestiary we find in Grandville, the zigzag rhythms of folk art, the stylized landscape of children’s illustration—and put them together in a new way. The surrealism of the museums may have the same relationship to the surrealism of the funny pages that any two animals have who descend from a common ancestor. (As often happens, the forebears may be more clearly evident in bad work than in good; Dali’s enormous debt to Edwardian illustration, and Rackham particularly, was already evident to George Orwell forty years ago.) “Surrealism,” properly so-called, may be, in a large sense—a sense that should include, as it often does not, “low” as well as “high” art—simply a fragile and flam-boyant subspecies on a much larger evolutionary ladder that springs ultimately from popular culture: Grandville and Tenniel, on this view, would not be surrealism’s neglected prophets, but its forgotten fathers; and Miró and Herriman not twin expressions of the Zeitgeist but artistic cousins, drawing on and transforming common sources. Herriman isn’t a wistful imitator, or an accidental equivalent, of Miró, but a diminutive cousin. Herriman’s relation to Miró isn’t like that of the Dog to the Moon, but like that of on of the insects in the Carnival to another: he doesn’t aspire wistfully to a higher sphere; he revels amiably in a common condition.

In another sense, the affinity between Herriman and Miró, the family resemblance of Kat and dog, has to do with another shared “project” of twentieth-century visual expression, and that is the desire to restore a “play element” to the plastic arts. The term, and the idea of “play” as an originating activity in culture, comes from Huizinga’s still provocative essay Homo Ludens. It was Huizinga who first noticed the absence of a tradition of festive comedy in the plastic arts, and he thought that this had happened because they had been denied, in their cultural youth, the qualities of high-spirited improvisation that were so basic to the musical arts, that is, drama, dance, and poetry.

The very fact of their being bound to matter and to the limitations of form inherent in it, is enough to forbid them absolutely free play and deny them that flight into the ethereal spaces open to music and poetry…. The architect, the painter, the sculptor, the draftsman, the ceramist and decorative artist in general all fix a certain aesthetic impulse in matter by means of diligent and painstaking labor. However much the plastic artist may be possessed by his creative impulse he has to work like a craftsman, serious and intent…. Where there is no visible action there can be no play.

In his witty and original essay about the comic Eden in art, “Dingley Dell & The Fleet,” Auden has something similar to say. His examples of comic pastorals, “Edens” in his sense, are all literary: Pickwick, Wodehouse, Firbank. It’s impossible to find a single case in Western art before 1900 of a comic Eden in Auden’s sense, a painted equivalent of Dingley Dell or Blandings Castle. (The possible exceptions are Bruegel’s peasant feasts and Rowlandson’s “Dr. Syntax” drawings, but Bruegel’s pictures finally have a conventional moralizing content, and Rowlandson’s drawings aren’t really original as designs: in the end, Rowlandson’s style is just a particularly chubby form of picturesque.) Even when the occasion is provided by illustration, the style just doesn’t seem to be available: Phiz, illustrating Dickens, does much better with Fagin’s gang than with Mr. Wardle and his family in Dingley Dell. The comic tradition in Western art is, before 1900, almost exclusively a satiric tradition, the tradition of caricature; while the pastoral tradition, the landscape of pleasure we find in Titian or Giorgione, is essentially serious.

The absence in the visual arts of what Auden meant by a comic Eden and the absence of what Huizinga called a play element in the visual arts before 1900 may point toward a deeper understanding of the affinity of Herriman and Miró. While Huizinga’s specific historical analysis of the absence of a play element in the plastic arts may not hold up—the notion that the plastic arts are sober because they were denied sufficient play in their infancy sounds suspiciously like the movie psychiatrist who explains the ax murderer’s behavior by the lack of finger painting in childhood—nonetheless thinking about play and the visual arts may help us to understand why a funny-page artist resembles an avant-garde god. It’s a commonplace, after all, that one of the things modern art has tried to do is to supply precisely this missing element of lyrical freedom, of improvisation, to the plastic arts.

The deep affinity of Kat and dog may reveal that the element that brings the two together is their very playfulness, and that we badly misread both modern culture and modern art if we mistake play for protest. It’s not just that a comic strip can be like a Miró; it’s that a Miró in many important ways is like a comic strip. Both are in revolt against the idea of a work of art as a solemn artifact, and seek to make instead a work of art that is celebratory, musical, free; that has the same qualities that we properly associate with the visionary dream of the world as a playroom, the dream of a comic Eden. Krazy Kat is not merely a mirror that reflects vanguard art in popular form, but a lens that allows us to see, by analogy, certain elements in modern art that have otherwise been hidden.

But if it’s important to see the shared common background, it’s just as, or even more, important to see that this affinity is interesting because it’s so exclusive. Herriman and Miró resemble each other, in highly specific ways. The popular tradition, as much as the vanguard tradition, changes through the acts of gifted individual artists. Even among those who accept the importance of popular imagery in the making of modern art, there’s still a tendency to see the popular tradition as a kind of folk tradition, fixed and unchanging: Lichtenstein responds to “comic books” rather than to Jack Kirby or Stan Lee; Seurat is in a dialogue with “advertising” rather than Cheret, and so on. At worst, popular imagery, and cartoon and comic strip in particular, are treated as though they were somehow natural rather than cultural forms, polished pebbles rather than finished artifacts. But “cartoon” doesn’t make comic strips; cartoonists do. To search for the source of the affinity of high and low in some impulse in history or culture should not neglect the gift that was required to wrench Coconino County from the bullpen of the New York Evening Journal, to put Eden on the funny page.

4.

Herriman continued to draw Krazy Kat until his death in 1944, but the inspiration falls off markedly in the 1930s: the drawing gets cruder, the characters get bigger, and thus the exquisite comic balance between landscape and figure is lost; backgrounds become schematic stage sets instead of lyrical designs. The one good thing that happened to Krazy Kat in the 1930s was that Herriman was allowed to produce color pages for the Sunday papers for the first time, bold areas of bright commercial-fauve coloring against solid black background. (Saul Steinberg thinks that we misunderstand Herriman’s intention if we see the dark Sunday strips simply as night pieces; he contends that Herriman wanted to represent the luminosity of color in the Enchanted Mesa, i.e., Monument Valley, and found that within the constraints of the commercial printing process, color could only have sufficient saturation and intensity by contrast effect if it was set against large areas of black.)

But Coconino remains, in its first premises, a happy place, and Herriman used the new effects—the nocturnes, the rougher drawing, the new proportion, the new sadness—to much better and more memorable effect in the series of drawings that he did to illustrate Don Marquis’s Archy and Mehitabel poems than he was able to in Krazy Kat itself. These are the best and most potent things that Herriman did after 1930, and they capture the melancholia that is the underside of every pastoral Eden from Watteau on. (Marquis’s poems deserve a new look on their own; they achieve in newspaper humor something like the same kind of effects that Herriman got in drawing, and with something like the same kind of authority.) Herriman’s drawings use everything that he had learned after two decades in Coconino, but they return his style to its urban origins: crawling along the baseboards, their squat and hairy forms silhouetted against the city tenements at night, lit sporadically from within, these creatures are the pioneers of a vision of urban squalor and sadness that has become one of the most powerful and potent in our visual life. It is a vocabulary of form that stretches directly from Herriman to other, lesser cartoonists like Gene Ahern, and then was most powerfully revived in R. Crumb’s underground cartoons of the late 1960s.

And then, in the late Seventies, the same vocabulary of form that Herriman first created in the Marquis drawings was given a new and unlooked-for tragic dignity and monumentality in the last paintings of Philip Guston. Guston’s paintings of bare, stubbled heads, cigarette butts planted dumbly in their mouths, of cold-water apartments with uncovered plank floors and light bulbs hanging naked from the ceiling, pullchains dangling like nooses, of piles of bare, bristled legs against molding, are all painted in an exquisite cartoon style whose scratched shadings and slapstick lines ultimately derive from Herriman. These images, among the most influential paintings of the last fifteen years, are a kind of majestic transposition of a theme first stated by Herriman in The Dingbat Family strips and then deepened by him in the 1930s. Like Lear borrowing from his Fool, Guston took Herriman’s melancholia and turned it into tragedy.

If we see Herriman as the progenitor of this tradition, the domino nudger par excellence, our image of his relationship to modern painting changes yet again, and with it our notion of the relationship between popular culture and modern art. The conventional account of popular art and modern art allows essentially two kinds of traffic. Popular culture can send up a naive form that the modernist then makes self-conscious and ironic; or the modernist can send down a self-conscious and ironic form that the popular culture then uses to sell something.

But this is art history as written by the Dingbats; popular imagery and its heroes are the unseen Family Upstairs, inviting paranoid and comic fantasies precisely because we refuse to find out very much about them. In the absence of any serious study of crucial “intermediate” figures, missing links like George Herriman, art history has been condemned to repeat certain clichés about popular culture and modern art without much variation or new evidence. The best way to reconcile barking dog and yearning Kat is just to look at what both forms are actually like. We owe the diligent authors and editors of the new collection of Herriman’s Krazy Kat a debt simply for reminding us that the best way to find out about the Family Upstairs is to walk up one flight and knock. And when we look at what George Herriman actually did, we see that the conventional straitjacketed picture of high and low in modern art is just false. Yet forty years after his death, art historians can still write, as one did only recently:

The cycle of exchange which modernism has set in motion moves only in one direction: appropriation of oppositional practices upward, the return of evacuated cultural goods downward. When some piece of avant-garde culture does re-enter the lower zone of mass culture, it is in a form drained of its original force and integrity.

Quick, Ignatz. The brick!

This Issue

December 18, 1986