1.

July 1986 was the fiftieth anniversary of the outbreak of the Spanish civil war. The war began as a rebellion of the Spanish army generals against the country’s democratically elected government, and ended three years later with the establishment of General Francisco Franco Bahamonde as dictator, a position he was to hold until his death in 1975.

Seen in retrospect, the war was the almost inevitable product of irreconcilable antagonisms within Spanish society that only a strong regime could hope to control. Instead of a strong government, however, the election victory of the Frente Popular in 1936 brought to office a cabinet of liberal republicans from minority parties, dependent for its continued existence on the cooperation of the Socialists and the as yet small Communist party. The Popular Front was threatened by forces that did not recognize its authority. On the right stood, among others, the Falange, a fascist party on the Italian model, and the Carlist Requetes, fanatically devoted to the Monarchy and the Catholic Church; on the left, a strong and widespread anarchist movement which proclaimed its intention to abolish not only the state but also the Catholic Church—and in fact burned many churches. Small wonder that two of the most impressive books on the politics of Spain in the twentieth century are entitled The Spanish Labyrinth1 and The Spanish Cockpit.2

Yet though its causes were so deeply rooted in circumstances peculiar to Spain (Basque and Catalan aspirations to autonomy added another unique complication), this war became, within days of its outbreak, the passionate concern of many people in Western Europe and America who had little or no understanding of its complex origins. The military rebels were supported and supplied by Hitler and Mussolini from the very beginning—German and Italian planes made possible the first military airlift in history, the transportation of Franco’s Moorish mercenaries from Africa to the mainland. The Madrid government represented the electoral victory of the Frente Popular, a left-to-center coalition like that which had brought the Socialist Léon Blum to power in France in the same year. So Spain became the first battleground of the antifascist war, a place where the advance of fascist power, unopposed and in fact at times actively encouraged by the British government, might be given a serious if not decisive setback.

“Madrid sera la tumba del Fascismo” was a slogan launched when Franco’s Moors and foreign legionaries were stopped dead at the edge of the city in November 1936; it was the hope, a not irrational one, of all progressive opinion in the West. It was not to be, of course; the French, cowed by threats from London that if they sold arms to the Republic they would have to face the consequences alone, joined Great Britain on the Non-Intervention Committee, which “was to graduate,” as Hugh Thomas puts it, “from equivocation to hypocrisy.” The British and French left the Republic to fight a professional army, backed by German and Italian weapons, specialists, and troops, with a rabble militia, without officers and heterogeneously armed, and dependent for heavy armament on Soviet shipments over the long sea route from Odessa through waters patrolled by Italian submarines, warships, and planes.3 The wonder is that the Republic survived so long; if it had managed to survive six months longer, in fact, it might have been saved at the last moment by the outbreak of the European war in September 1939.

The long, heroic resistance of the Republic aroused in its time the enthusiastic admiration of liberal and leftwing circles in the West. This was true above all of writers, who were especially sensitive to the threat of fascism, both abroad and at home. “Our prerogatives as men,” Louis MacNeice wrote in a poem addressed to Auden in 1936,

Will be cancelled who knows when.

Still I drink your health before

The gun-butt raps upon the door.4

Later, recalling a visit to Spain just before the war broke out, he wrote of leaving the country,

…not realising

That Spain would soon denote

Our grief, our aspirations;

Not knowing that our blunt

Ideals would find their whetstones, that our spirit

Would find its frontier on the Spanish front,

Its body in a rag-tag army.5

MacNeice spoke for an entire generation of writers, British, European, and American; the war was midwife to an abundant and talented literature, a “burst of creative energy,” as Hugh Thomas puts it in his definitive history of the war, “which can be argued as comparable in quality to anything produced in the Second World War.”

The fiftieth anniversary has revived interest in this struggle that now seems so remote even to those who took an active part in it. In Washington, for example, a conference organized by the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of American History recently discussed the impact of the war on the American political scene and in particular the role of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. It was addressed by historians and veterans (one of them, Professor Robert Kolodny, was both) and concluded with a screening of a remarkable film, The Good Fight, which through interviews with veterans and contemporary photographs and newsreels re-creates the atmosphere of the time and explores the motives of the participants.

Advertisement

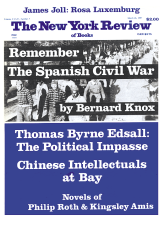

Similar conferences are being planned or already announced at more than one university; meanwhile a number of new books on the war and an important reissue of an old one have already appeared, and there are no doubt more to come. The reissue is Hugh Thomas’s basic history, The Spanish Civil War. It was first published in 1961; in 1977 a “revised and enlarged edition” incorporated the new material, much of it published in Spain, which had come to light in the interval. Now Harper and Row has produced what it calls a “third edition,” with a “new preface by the author.” There is indeed a new preface—less than two pages in length—but otherwise the text is unchanged from the 1977 edition. The misprints remain uncorrected (two lines missing and two repeated on page 862, for example) and so do slips of the pen (a remark of Orwell attributed to Auden on page 653).

More important, no notice is taken of material published after 1977 that calls for correction or addition. In his account of the arrival of the Eleventh International Brigade at Madrid in November 1936, for example, Thomas has the march led by “a battalion of Germans with a section of British machinegunners, including the poet John Cornford.” In fact, Cornford and the present reviewer were in the Second Battalion, the French “Commune de Paris.”6 This error was corrected in an article published in The New York Review in 1980. 7

As for additions, Peter Wyden’s book The Passionate War8 provides new evidence about the massacre of prisoners by Franco’s troops at Badajoz in 1936, a subject for bitter controversy ever since the first reports of these mass shootings in the bullring reached the outside world. Wyden interviewed a Portuguese laborer who was hired to help bury the Republican corpses (after they had been burned); the mass grave was forty meters long, ten meters wide, and one and a half meters deep. Wyden also reproduces a still from a Pathé newsreel which shows the heaps of burned corpses awaiting burial outside the bullring.

Still, even though it is regrettable that the opportunity to bring it up to date was not seized, Thomas’s book is the fullest and best one-volume nonpartisan history of the war in English.9 Starting from the overthrow of the monarchy in 1931 Thomas constructs a clear and skillfully paced narrative which gives equal weight to the military, political, and economic aspects of the conflict. His analysis of the dissension on both sides is illuminating and fair-minded, though on rereading I detected a somewhat disproportionate admiration for the way Franco succeeded in manipulating his warring constituencies to his own advantage, unlike the unfortunate Republic, which resorted to armed repression in Catalonia in 1937 and in its final days was unable to prevent the military commanders at Madrid from surrendering unconditionally and so ending the war.

A subtle bias perhaps shows itself in the fact that victims of repression are either “shot” or “executed” in Franco territory whereas in the Republic they are usually “murdered.” The distinction may stem from Thomas’s generalization that

though there was much killing in rebel Spain, the idea of limpieza, the “cleaning up” of the country from the evils which had overtaken it, was a disciplined policy of the new authorities and a part of their program of regeneration

whereas

in Republican Spain most of the killing was the consequence of anarchy, the outcome of a national breakdown, and not the work of the state.

Since the “national breakdown” had been mainly provoked by the rebellion of the military authorities and since the policy of limpieza entailed what Thomas calls “a wave of executions which began in 1936 and continued, if the truth be known, until 1941 or 1942,”10 this summary is, to say the least, disingenuous.

It is true that in Franco territory the killings were carried out by men in uniform, but that is hardly warrant for the distinction between “execution” and “murder.” Given the scale and difficulty of the undertaking, however, these are minor lapses; the task of maintaining an impartial tone in a field where controversy rages on almost every point (Thomas’s bibliography includes nearly nine hundred publications) must have been exacting in the extreme and one can only admire the careful weighing of the evidence and its full citation, which make this book still, for the English-speaking world, the standard history of the war.

The illustrations in this edition of the book, unlike those in the first, consist entirely of photographs of the leading personalities on both sides, and since one of Thomas’s strong points is his incisive delineation of character—his portraits of Franco, Manuel Azaña, the Republican president, and the anarchist leader Durruti, for example, are particularly memorable—this seems appropriate. But the war was the first to be fully documented by photographers. “This,” said a Catalan official to Claud Cockburn, “is the most photogenic war anyone has ever seen.” The visual aspect of it is handsomely covered in a collection of more than 350 illustrations: The Spanish Civil War: A History in Pictures. They are arranged chronologically from the fall of the monarchy in 1931 to the collapse of the Republic in 1939; the first photograph shows triumphant Republicans standing on an overturned equestrian royal statue and the last a Republican soldier interned in France, giving a light to a sentry through the wire. These images of the war come from both sides of the lines and they are supplemented by a generous selection of those posters which, in the hands of the Republican artists, marked a new level in the techniques of visual propaganda.

Advertisement

There are unfortunately very few pictures from what was regarded at the time as the epic phase of the war, the defense of Madrid in November and December of 1936. There are photographs of bombs and artillery shells exploding in the Madrid streets, but none of the fighting in the Casa de Campo and the University City, except for one, labeled “posed picture,” which shows soldiers sitting and standing up, firing out of the open windows of what is supposed to be one of the university buildings. Never, I suspect, was a picture more posed. 11 In our building, Filosofía y Letras, we fired our Lewis guns through holes we had made in the brickwork just above floor level and moved on our hands and knees below the level of the windows until we managed to barricade them with huge volumes we found in the basement (some of them dealt, in German, with Indian religion and philosophy). It is not that photographs of this part of the front were unavailable; the December 1936 issue of Life magazine had a number of pictures that showed the strange landscape of the Ciudad Universitaria, a world of half-ruined buildings fronting great bare expanses of grass and concrete on which nothing living was to be seen. And the film Mourir à Madrid has a sequence shot in the philosophy and letters building at night which shows International Brigade troops repelling an attack.

This is a minor complaint, however, that of a veteran who finds his own battles slighted; on the whole this is a splendid selection. And it is preceded by an introduction by Raymond Carr, a thoughtful and judicious assessment of the causes, course, and effects of the war by a noted authority on modern Spanish history.

The impact of the war on writers and intellectuals was, as Carr says in his introduction, “tremendous.” That impact is the focus of two new anthologies: Spanish Front: Writers on the Civil War edited by Valentine Cunningham and Voices Against Tyranny: Writing of the Spanish Civil War edited by John Miller. Cunningham is a tutor in English literature at Oxford and has previously edited an anthology entitled Spanish Civil War Verse,12 which included much material that had not been previously published or collected; the book is remarkable for its informed and penetrating critical introduction. His new anthology contains more prose than verse; this is understandable since, as he remarked in the preface to the earlier collection, many of the poems in it “deserve…to be known only to readers with a particular interest in the literature of this war.”

In the new volume there is much that is familiar—poems by Auden, Spender, George Barker, and John Cornford, prose extracts from Koestler, Orwell, Bernanos, Regler, and Esmond Romilly’s Boadilla, perhaps the most moving of all the eyewitness accounts by combatants. But there is also much that is unfamiliar and very good to have. There is, for example, a previously unpublished letter of Stephen Spender to Virginia Woolf, written in April 1937 after a visit to Spain, which urges her to discourage Julian Bell from joining the Brigades and laments the fate of those volunteers who “should never have joined” and find themselves unable to stand the stress of combat. (Not that they were shot as deserters, which would have been their lot in the 1914 war; they were, to quote Spender, “quite well treated in a camp.”)

There is also a letter from Simone Weil to Georges Bernanos; she has just read Les Grands Cimetières sous la lune, his terrifying account of the fascist massacres on Majorca, and writes that she has had an experience herself “which echoes yours.” Not that the killings carried out by the Anarchists, one of whose columns she had joined, were on the scale of those organized by the Italian Fascist Rossi on Majorca; but, as she puts it, “numbers are perhaps not the main thing in such matters. The real point is how murder is regarded.” Also included is Anthony Blunt’s dismissal of Picasso’s series of etchings Sueño y Mentira de Franco as the work of “a talented artist struggling to cope with a problem entirely outside his powers” and the heated correspondence, including a rebuttal by Herbert Read, which followed the publication of Blunt’s article “Picasso Unfrocked” in The Spectator.

One novel feature of this anthology is its emphasis on the role of women in the war. “The fairly well-known male story of concerned male artists and writers,” Cunningham says in his introduction, “has now to be supplemented by the story of engaged women writers and artists.”13 A section captioned (rather strangely) “Women Writing Spain” includes items from Virginia Woolf (“Remembering Julian”), Rosamond Lehmann, and Sylvia Townsend Warner, as well as a moving account of the work of a British medical unit in the Republican Ebro offensive in 1938. It is a memoir, previously unpublished, written by Nan Green, a nurse in the unit, whose husband, serving in the British Battalion, was killed in the course of that operation.

Cunningham has obviously tried hard to find writing from adherents of the fascist cause but the pickings are slim. Evelyn Waugh’s reply to the Left Review questionnaire—“If I were a Spaniard I should be fighting for General Franco”—and Roy Campbell’s scurrilous poem addressed to Azaña are well known. Cunningham has, however, unearthed one real gem: Hilaire Belloc’s account of his interview with Franco just before the fall of Catalonia. Belloc is deeply moved by the site of their meeting, the “Marches of the Ebro, where Charlemagne first established the Christian bastion against that attack which threatened to destroy, to overwhelm, all the Christian thing.” The attack in question was the advance of Islam, the “violent flame” by which “Christendom of the east and of the Mediterranean had been three-quarters overrun.” Franco was “one who had fought that same battle which Roland in the legend died fighting and which the Godfrey in sober history had won when the battered remnant, the mere surviving tenth of the first Crusaders, entered Jerusalem.”

Belloc is apparently unaware of the fact that it was Franco who brought Islam back to Spain more than four hundred years after Isabella la Católica had broken its power at Granada. The key units of the Army of Africa which advanced on Madrid were the Regulares, Moorish mercenaries originally recruited to fight against their own people in Morocco;14 their “established battle-rite of castrating the corpses of their victims [was] usually,” says Thomas, “restrained by their commander General Yagüe.”15

The other anthology of writers, Voices Against Tyranny (introduction by Stephen Spender), is a smaller book and its excerpts are most of them much longer than those in Cunningham’s book. There is some duplication in the two volumes but prominent among the items peculiar to this volume are a story by Hemingway, “The Butterfly and the Tank,” which first appeared in Esquire in 1938, a story by Dorothy Parker which remained unpublished until 1986, when it was printed in Mother Jones, an extract from Salvador Dali’s autobiography with a typically idiosyncratic view of the war, and a fascinating chapter from the autobiography of Luis Buñuel, which was published in 1983.

In the article about the winter fighting in Madrid published in these pages16 some years ago I remarked on the surrealist quality of life in the city in those days and surmised that Buñuel, if he had been there, would have felt quite at home. It turns out that he was in fact in Madrid when the rebellion began and stayed there until September; he then left for Paris, where he had been assigned to work with the Republic’s ambassador. But he did not feel at all at home in Madrid. “I,” he writes, “who had been such an ardent subversive, who had so desired the overthrow of the established order, now found myself in the middle of a volcano, and I was afraid.” He was torn between his “intellectual (and emotional) attraction to anarchy” and his “fundamental need for order and peace.”

Two more new books on Spain deal not with the writers and artists but with active participants in the military operations. The Signal Was Spain by Jim Fyrth is a well-researched account of the Aid Spain movement in Great Britain; it recreates from archives and interviews not only the collection of money and food for the Spanish Republicans but also the vital contribution made by the two hundred men and women who went to Spain to work with medical or relief organizations. The book is an authoritative account by a professional historian of what the publisher rightly calls “one of the most spontaneous and inspiring expressions of international solidarity the country has ever seen.”

Fyrth expressly and successfully contests A.J.P. Taylor’s judgment that the Spanish war “remained very much a question for the few, an episode in intellectual history…. Most English people displayed little concern.” He covers in detail the campaigns to raise money for food, food ships, trucks, and orphanages, as well as the evacuation and settlement in England of four thousand Basque children. The longest and most interesting sections of the book are those that deal with medical aid, with the doctors, nurses, and ambulance drivers working under the Spanish Medical Aid Committee—services which, as Hugh Thomas says, “played almost as great a part as the International Brigades.” Julian Bell was killed driving an ambulance at Brunete in 1937, and according to Thomas (and many others) Auden served briefly as a stretcher-bearer in one of these units. “This,” says Fyrth, “is part of the mythology of the war…. If Auden served as a stretcher-bearer, it was not with the SMAC unit.”

Another element of the mythology of the war, the belief that Dr. Norman Bethune started the mobile blood transfusion service in Madrid, is quietly disposed of. “The Madrid service had in fact been started at the beginning of the war by Dr. Gustavo Pittalugo, Professor of Haematology and Parasitology at Madrid University.” What Bethune did was to expand the unit until by March 1937 he was doing up to one hundred transfusions a day and by the autumn of that year the unit was “supplying blood to several fronts” and to “one hundred hospitals in the central sector alone.”

The other new book is by a participant in the fighting. Prisoners of the Good Fight by Carl Geiser is an account of what happened to Americans of the Lincoln Battalion who were, like him, captured by Franco troops. Of the 287 who were taken prisoner, 176 were killed on the spot; Franco had ordered that foreigners unwise enough to surrender should be treated like Spaniards and shot out of hand. However, after the Republicans captured 496 Italian soldiers at Guadalajara in March 1937, American and British prisoners were, for a short time, spared and reserved for future exchanges. (The Italians, to give them their due, had not followed the Franco practice of shooting prisoners.)

Geiser’s book deals with the experiences of the 106 Americans who waited in Franco prisons for exchange during or release at the end of the war; some did not get out until 1940. Geiser himself was in great danger since he had been political commissar of both the Lincoln and the Mackenzie-Papineau battalions; when he identified himself as political commissar to the Italian officer who had captured him the reaction was immediate: “an expressive movement of the index finger from one side of the throat to the other.” Once handed over to Spanish officials, however, Geiser got rid of his officer’s jacket and for the thirteen months of his captivity managed, with the cooperation of his fellow prisoners, to conceal his rank from his jailers.

Since Geiser gives detailed and vivid accounts of the capture and prison experiences of all the Americans captured on different fronts and at different stages of the war, the narrative is at times a little confusing, but the book is valuable for its wealth of firsthand accounts of capture and prison activity. In Geiser’s prison at San Pedro de Cardeña the men produced a clandestine newspaper, the Jaily News, cooperated in the escape of some German Internationals who were scheduled to be handed over to the Gestapo, and set up an “Institute for Higher Learning” with seventeen classes ranging from beginning Spanish to calculus. The book is a remarkable record of a little-known, indeed to most people quite unknown, story of American courage and endurance.

2.

Recently, however, the American volunteers in the Republican army have been portrayed as, at best, simple-minded dupes of Stalin’s Machiavellian designs. This was the theme of a long article in The Washington Post, “My Uncle Died in Vain Fighting the Good Fight,” by Ronald Radosh.17 In a later article in The New Criterion, “‘But Today the Struggle’: Spain and the Intellectuals,”18 Radosh dismisses the Republican cause as one which, in the light of what is now known about Russian interference and manipulation, should be wholly repudiated by intellectuals. “In 1986, those who still respond to the Spanish Civil War as ‘our cause’ have no excuse.”19

It is of course true, as is evident from many of the texts collected in Cunningham’s anthology, that many writers and intellectuals who initially supported the Republic had second thoughts later, George Orwell prominent among them. Yet even though the role of the Russian-directed political police in the last year or so of the Republic’s life has been common knowledge for at least twenty years (Radosh has no new evidence to show), few, if any, of those who once championed the Republic, with rifle or with pen, have seen fit to repudiate the cause entirely, any more than Orwell did.

Even some of those who fought in the International Brigades have had to recognize, sooner or later, unpleasant truths that they had no inkling of at the time. I am myself a case in point. I fought, with John Cornford, in the machine-gun company of the French Battalion of the Eleventh Brigade at Madrid in the winter of 1936. When, some years later, Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls appeared, though full of admiration for the novel and the remarkable illusion it creates of Spanish character and even of Spanish speech, I was outraged by its portrayal of the French Communist official André Marty as a murderous, incompetent fanatic. I had known him at Albacete in October 1936, when the Eleventh Brigade was being formed and had found him a kindly patron of our small English section (there were only twenty-one of us), which tended to get overlooked when equipment, and for that matter rations, were distributed. I expressed my indignation about Hemingway’s caricature (for so it seemed to me then) to friends in New York and one of them suggested that I write an article about Marty as I knew him. I did, and it was published in The New Masses in November 1940. There was nothing in it that was not true but what I had not realized was that the Marty I knew in October had in fact become, long before the war ended, exactly the kind of murderous witch hunter who makes such an unforgettable impression on the readers of Hemingway’s novel.

When, much later, I recognized the justice of Hemingway’s indictment, I felt considerable embarrassment about the article I had published. But I found this no reason to repudiate the entire Republican cause. War is an ugly business at best; as Thucydides said long ago, it is a teacher of violence and reduces most men’s tempers to the level of their circumstances. It brings out the worst in some men and the best in others. And in most of those who fought for the Republic it brought out the best.

According to Radosh, the Spanish Republic had become, well before the end of the war, “what its enemies called it, a puppet of Moscow”—the phrase is that of the historian of the Comintern, E.H. Carr.20 There is some exaggeration here—the repeated attempts of Juan Negrin, the Socialist doctor who became president in 1939, to negotiate a peace in 1938,21 for example, were quite contrary to the Communist party’s policy. But it is true that by late 1937 the Communist party and its Comintern and Russian “advisers” were in firm control of the Republican armies and were exercising civilian political control through a Russian-style secret police. This state of affairs had come about not only because the Soviet Union was the Republic’s sole source of modern weapons but also because the Communist party, an insignificant minority when the war began, had won widespread support by its capacity for organizing an army that, unlike the militia columns of the opening days of the war, could fight successfully against regular troops.

But it does not follow from this, as Radosh and others seem to believe, that a Republican victory would have resulted in a Spain comparable to the present Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe. “The meaning of Soviet domination,” he writes in a letter to The Nation,22 “was succinctly explained by Dolores Ibarruri, who, speaking from her sanctuary in the Soviet Union in 1947, said, ‘Spain was the first example of a “people’s democracy.” ‘ ” But such a development is beyond belief. If the Republic had won the war, the need for Soviet arms and a disciplined army would have vanished and so, inevitably, would the dominance of the Communist party.

The Party was already unpopular, to say the least. One of Togliatti’s dispatches to Moscow, explaining how it was possible for General Casado, against Communist opposition, to end the war in 1939 by surrendering the Madrid front, speaks of

an explosion of all the hatred for our party and spirit of revenge of anarchists, provocateurs, etc., etc…. The p[arty] was surprised by this wave of repression, which moreover highlighted our weaknesses, especially in relation to our links with the masses.23

Indeed, the success of Casado’s coup is in itself a comment on the weakness of the Party’s hold over the armed forces. And in any case the idea of Republican Spain as a “people’s democracy” like Hungary or Czechoslovakia is ridiculous. Those countries have been held down only by the presence and on occasion the active intervention of Russian troops. Stalin had more to worry about than Spain in 1939 and the early Forties, and in any case he did not have the capacity to maintain an army of occupation there over a long and vulnerable sea route. And even if he had tried he would have had to reckon with the recalcitrant opposition of the Spanish character to any form of control.

Thomas opens his history with a quotation from Angel Ganivet which explains much about the war that may seem strange to readers brought up in more or less disciplined societies. “Every Spaniard’s ideal,” it runs, “is to carry a statutory letter with a single provision, brief but imperious: ‘This Spaniard is entitled to do whatever he feels like doing.”‘ It is relevant, too, that now, under the democratic monarchy, the Communist party is once more what it was at the beginning of the civil war, a minority party.

The fact that continued Soviet control of a victorious Republic would have been beyond Stalin’s powers negates Hugh Trevor-Roper’s argument, cited by Radosh in that same letter to The Nation, that Stalin, “friendly to Hitler and hostile to the West…might have provided the Germans with the transit through Spain that Franco steadfastly refused.” And a victorious Republic would certainly not have sent, as Franco did, a crack infantry division to fight by the side of the Wehrmacht in Russia.

In his long article in The New Criterion Radosh’s main concern is with the intellectuals and particularly the writers who supported the Republic. He spends much of his space dealing with the case of Stephen Spender, which he finds “particularly instructive.” Spender, in his introduction to Miller’s Voices Against Tyranny, points out that

much of the literature of the Spanish Civil War written on the Republican side seems to show that the writers of it felt that there was a “truth” of “Spain” that remained independent of, and survived the mold of, Communism into which successive Republican governments were forced.

Radosh is skeptical of any such “truth” and cites against its existence the case of Spender himself. He compares the letter Spender wrote to Virginia Woolf in 1937 with his remarks about John Cornford, printed in a review Spender wrote in 1938.

The letter states that “everything one hears about the International Brigade in England is lies” and complains of “the lies and unscrupulousness of some of the people who are recruiting at home.” He hopes that Virginia’s nephew, Julian Bell, will not join the brigades.

The qualities required apart from courage, are terrific narrowness and a religious dogmatism about the Communist Party line, or else toughness, cynicism and insensibility. The sensitive, the weak, the romantic, the enthusiastic, the truthful live in Hell there and cannot get away.

He goes on to denounce the lie which he attributes to the Daily Worker, the British Communist newspaper, that “people can leave the Brigade whenever they like. On the contrary, one is completely trapped there.” He mentions the particular case of his “greatest friend” who “collapsed” on the fourth day of the Jarama battle. Returned to base at Albacete he tried to escape, was caught and sent to a “labor camp.” Spender’s request to have him attached to himself as a secretary was refused.

It is true that before mid-1937, when the brigades were formally inducted into the Republican army, there was some confusion about the term of the enlistment of foreign volunteers. Esmond Romilly was allowed to go home after the almost complete annihilation of the British unit of the Thaelmann Battalion of the Twelfth Brigade at Boadilla in December 1936 and I, wounded in the same engagement, was also sent home, though it is true that I had, as a result of the wound, nerve damage in my right arm and shoulder and would have been of no use as a rifleman. As a matter of fact, one young man who shot himself in the foot the first time we came under artillery fire was also sent home; in the British army in the 1914 war he would have been court-martialed.24

When, however, the British contingent, no longer a handful of men lost in a French or German unit, became the British Battalion, the rules had to be tightened up. The Spaniards were in for the duration, and the German and Italian soldiers of the brigades, as well as the men from other countries that had reactionary regimes, had no home to go to. It would have been disastrous for morale if one national section had enjoyed the privilege of pulling out at will. Spender recognizes, in the letter, that “the discipline is not so bad as that of Capitalist armies; deserters are not shot but quite well treated in a camp.”

As for the qualities required for life in the brigades, “narrowness and religious dogmatism about the party line” were rare, and courage, toughness, cynicism, and insensibility are the hallmark of seasoned combat veterans the world over. They have to develop insensibility to the sight of what metal can do to human flesh, and they very soon develop a cynical view of the wisdom of higher headquarters and the rhetoric of politicians. In the film The Good Fight one veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade talks with sarcastic vigor about people who came out to Spain and urged the volunteers to fight against fascism. “What the hell did they think we were doing?” he asks indignantly. And the British Battalion, which after being bled white in the Jarama battles then spent month after month in the trenches there adopted with enthusiasm a song written by one of their number which shows little of that religious dogmatism about the party line Spender complains of. It is sung to the tune of “Red River Valley” and the first verse goes:

There’s a valley in Spain called Jarama,

That’s a place that we all know so well,

For ’tis there that we wasted our manhood

And most of our old age as well.25

The terms of Spender’s letter are clearly inflated and sentimental; the vision of the brigades as Hell for the weak, the sensitive, and romantic reminds one irresistibly of so many English accounts of the sufferings of a boy with an artistic soul at a public school. His letter is the understandable reaction of a man of keen sensibilities, who had always had pacifist leanings, to the harsh realities of war, a reaction compounded by concern for a close friend who was, as he puts it, “hopelessly caught in the machinery” and for whose plight he felt himself to some extent responsible.26

Radosh contrasts this letter with a passage from Spender’s review of a volume commemorating John Cornford, published in 1938. Cornford is there described as one who exemplified “the potentialities of a generation” that was fighting “for a form of society for which it was also willing to die.” “How,” asks Radosh, “are we to judge a writer who says one thing to a friend in private and quite the opposite to an innocent and credulous public on such a momentous issue?”

I cannot myself see that there is any cause to reproach Spender in this matter. He was writing about two very different men; his friend who collapsed under the strain of combat and a man of whom he says, earlier in the review, that his own writing and the essays about him give “a picture of a character so single-minded, so de-personalized, that one thinks of him, as perhaps he would wish to be thought of, as a pattern of the human cause for which he lived, rather than an individual, impressive and strong as his individuality was.” In a part of the letter to Virginia Woolf that Radosh ignores he had written: “For people who can face all this, the Brigade is all right.” John Cornford could face “all this,” and more.

How much Radosh is out of touch with the material he is using is clear from some of the remarks he makes on these texts. “When Spender wrote the letter to Virginia Woolf,” he wonders, “was he secretly hoping that she would show it to Cornford before he made the fatal decision to join the battle, as Cornford wrote, ‘whether I like it or not’?”

It is hard to know where to begin unraveling the compacted tangle of Radosh’s errors here. John was already six months dead when Spender wrote his letter. And to anyone who knew John the idea that he would pay any attention to advice from Virginia Woolf is ludicrous; in any case there is no reason to think that they ever met. Radosh was probably thinking of Julian Bell when he wrote “Cornford” but this is no mere slip of the pen, as is clear from his quotation from Cornford’s letter; it is a mistake which betrays a disturbing unfamiliarity with the evidence. And that quotation, “whether I like it or not,” has nothing to do with joining the brigades; it comes from a letter written from Catalonia in August 1936 when John was already fighting with a POUM column on the Aragon front. He speaks of feeling lonely and thinking of using his press card to get back to Barcelona. “But the question was decided for me. Having joined, I am in whether I like it or not.” Radosh does not quote the next words; they would clash with his image of the “martyred John Cornford.” They are: “And I like it. Yesterday we went out to attack, and the prospect of action was terribly exhilarating.”

Radosh has a slapdash way with quotations; one more example. He cites from Orwell (his major, and quite inappropriate, example of a writer who turned his back on the Republic) a harsh dismissal of John Sommerfield’s Volunteer in Spain as “sentimental tripe.” The full sentence reads:

Seeing that the International Brigade is in some sense fighting for all of us—a thin line of suffering and often ill-armed human beings standing between barbarism and at least comparative decency, it may seem ungracious to say that this book is a piece of sentimental tripe. 27

He wrote these words in July 1937, after his return from Barcelona. In 1942, in his essay “Looking Back on the Spanish Civil War,” he wrote, “If it had been won, the cause of the common people everywhere would have been strengthened.”

Radosh is careless about his facts, too. In support of his statement that Stalin “purposely never gave the Republic enough arms with which to win” he describes the Russian materiel that reached Spain in October 1936 as “tanks, planes, and artillery…of a limited caliber—no match for the heavy equipment supplied by the Germans and Italians.” Thomas has a different story to tell.28 The fighter planes which arrived in October were the “fastest in Europe…technically superior to their German and Italian equivalents.” The ten-ton tanks (T–26) “were heavily armored, cannon-bearing machines, of a more formidable type than the three-ton Fiat Ansaldos and six-ton Panzers Mark 1…which had no cannon, only machine guns.” And the Russian antitank guns were “superior to any German models then available.” (In fact, Franco’s munition factories used them as a model rather than the German product.) As for quantity, even though after the closing of the sea route by Italian naval action in mid-1937 supplies could reach the Republic only when the French government from time to time opened the frontier, Stalin delivered 900 tanks as against 200 sent by Hitler and the 150 sent by Mussolini, and 1,000 aircraft as compared to the 1,200 sent by the fascist dictators. Stalin was no philanthropist but in the matter of heavy equipment he obviously delivered what he had been paid for.

Radosh spends much of his time castigating British and American intellectuals and writers for their blindness and hypocrisy but the only Spanish writer he pays any attention to is García Lorca and then only to quote Salvador Dali to the effect that Lorca’s death “was exploited for propaganda purposes” and that “personally the poet was ‘the most apolitical person on earth.’ “

The implication is that Lorca’s murder was not something that could be blamed on the Nationalists, it must have been an accident or the result of a private quarrel. This is of course rubbish. Certainly Lorca was not a political figure like his friend, the Communist poet Rafael Alberti, but he had enough counts against him to be shot ten times over by the standards of what passed for justice in fascist Spain. He was the brother-in-law of the Socialist mayor of Granada (who was also shot); he was the director of an experimental traveling theater—La Barraca—which had been created by the left-wing student organization FUE; he was the author of a famous ballad which cast as the villains of the piece the Guardia Civil, the hated militarized police whose black patent-leather hats are to be seen on so many photographs of Spanish peasants on trial for their lives or being led off to be shot.29

As if this were not enough, he had, in the months preceding the rebellion, delivered the speech of welcome at a banquet for Alberti (who had just returned from the Soviet Union); he had signed, together with Alberti, Luis Cernuda, and Manuel Altolaguirre a manifesto demanding the release of the Brazilian revolutionary Luis Carlos Prestes; he had attended a banquet in honor of Malraux and other French writers at which the crowd sang the “Marseillaise” and the “Internationale.” He had also, in an interview published in the widely read Madrid newspaper El Sol, referred to his home town Granada as “an impoverished, cowed town, a wasteland populated by the worst bourgeoisie in Spain today.”30 He was, of course, a poet, not a political figure, as he himself said more than once,31 but he had clearly identified himself with the Republican cause and so signed his own death warrant.

He was not the only writer to proclaim his loyalty to the Republic. One of the few souvenirs I still have of my time in Spain is a tattered bundle of issues of a literary magazine published in Valencia in 1936 and 1937. Hora de España, it is called; among the contributors are Rafael Alberti, Manuel Altolaguirre, José Bergamín, Luis Cernuda, Rosa Chacel, Juan Domenchina, Leon Felipe, Juan Gil-Albert, Jacinto Grau, Jorge Guillen, Miguel Hernández, Antonio Machado, and Emilio Prados—an honor roll of modern Spanish literature. With the fall of the Republic all of them went into exile, with the exception of Hernández, who died in a Franco jail in 1942. Spanish writers knew what Franco’s Spain stood for, they knew that when Millán Astray interrupted Unamuno’s repudiation of the Nationalist cause at Salamanca with the cry, “Death to the intellectuals! Long live Death!”32 he was only putting into words the deepest feelings of Franco and his supporters.

Some of the foreign volunteers knew enough about Spain to share the feelings of its writers, but for most of them the decisive element in their decision to go to Spain was the fact that Franco was supported by Hitler and Mussolini. For those in Western Europe and America who viewed the steady advance of fascism with growing apprehension, and the spineless acquiescence in fascist aggression of the British and French governments with contemptuous anger, the resistance of the Spanish people to the military rebellion was an inspiration and a challenge. And for those who came from what Auden in his famous poem called “the unjust lands,” Spain was the place where after years of clandestine, anonymous activity, of isolation and eventual exile in countries that were far from hospitable, they could at last face their enemy in the open, as soldiers, rifle in hand. The Republic, with all its faults and weaknesses, and even in its final phase of subjection to Communist control, was still on the right side of the major war that was in the making and so soon to come. The American volunteers of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade were known to the FBI as “premature anti-Fascists”; it was an accusation but it is a designation that all those who fought for the Republic can accept with pride. We were ahead of everybody else in something that had to be done.

That we lost was a tragedy for Spain, which was condemned to forty years of stifling obscurantist dictatorship. “History to the defeated,” Auden wrote, “May say Alas! but cannot help or pardon.” He suppressed the poem in later editions of his collected poems and once wrote on a copy of the pamphlet in which it first appeared, “This is a lie.” Radosh approves: “Auden subsequently—to his honor—repudiated” the poem. But Auden was wrong to do so; what he had written is the bitter truth. Ask the Cuban exiles, the Hungarian freedom fighters, the Czechs, the survivors of the half a million Spaniards who fled from Franco’s firing squads over the French frontier in 1939. Radosh goes farther even than Auden; he will not have history even say “Alas!” But Albert Camus summed it up for all of us who still mourn the Republic. “It was in Spain,” he wrote in 1946, “that men learned that one can be right and yet be beaten, that force can defeat spirit, that there are times when courage is not its own reward. It is this, no doubt, which explains why so many men, the world over, feel the Spanish drama as a personal tragedy.”33

This Issue

March 26, 1987

-

1

By Gerald Brenan (1943).

↩ -

2

By Franz Borkenau (1937).

↩ -

3

For Italian sinkings of supply ships (not only Russian but also British, French, Greek, and Danish) see Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, pp. 740 ff. Mussolini boasted in September 1937 that he had sunk nearly 200,000 tons (Thomas, p. 743) and by October, according to Thomas (p. 745), “the blockade of the Mediterranean was now almost complete.”

↩ -

4

The Collected Poems of Louis MacNeice (Oxford University Press, 1967), p. 75.

↩ -

5

The Collected Poems of Louis MacNeice, p. 112.

↩ -

6

Thomas has confused our section with the English group (of which Esmond Romilly was a member) that served in the German Battalion of the Twelfth Brigade. They arrived at Madrid several days later.

↩ -

7

Bernard Knox, “Remembering Madrid” (November 6, 1980).

↩ -

8

Simon and Schuster, 1983, pp. 136–138.

↩ -

9

Gabriel Jackson, A Concise History of the Spanish Civil War (London: Thames and Hudson, 1980) is also worth consulting. Antony Beevor’s The Spanish Civil War (Bedrick, 1983) is a much fuller treatment, especially notable for its expert discussion of the military operations. (Beevor was trained at Sandhurst and served for five years as a regular officer in the British army.)

↩ -

10

Jackson’s figures for executions and reprisal killings (as revised downward in his 1980 paperback edition) are: 20,000 on the Republican side, “committed mostly during the first three months of the struggle,” and on the other side “the Nationalists, counting the entire time from July 1936 to the end of the mass executions in 1944, liquidated 150,000 to 200,000 of their compatriots.”

↩ -

11

The same picture appears in Beevor’s book with the caption: “Rebels defend the telephone exchange in Barcelona, 1936.” This may well be right; the men in the picture look like regular Spanish army personnel.

↩ -

12

Penguin, 1980.

↩ -

13

The film The Good Fight has a similar emphasis; some of the most impressive figures among the veterans who appear in it are women—two nurses (one of them black) and a truck driver.

↩ -

14

Franco had used the Moors in Spain before—in the ferocious repression of the revolt in Asturias in 1934, where they were allowed to rape as well as kill indiscriminately.

↩ -

15

Thomas, p. 375, footnote 1. The other component of the Army of Africa, which relieved Toledo and reached the outskirts of Madrid in November, was the Tercio, the Spanish foreign legion. It consisted mainly of Spaniards, though there was also a large Portuguese contingent. According to Beevor (p. 52), it was “composed in large part of fugitives and criminals.” There were also some French in the legion, as I found out at Madrid. At one point in the fighting in the University City we were in trenches very close to the enemy; they began to shout insults and threats at us in what was clearly, judging from its expert profanity, native French. When I asked our Frenchmen of the Commune de Paris Battalion what Frenchmen would be doing in the Spanish foreign legion, they said: “Our legion will take foreigners in with no questions asked, but if you are a Frenchman on the run from the police, you have to go to the Spaniards.”

↩ -

16

November 6, 1980.

↩ -

17

April 6, 1986.

↩ -

18

October 1986.

↩ -

19

Radosh’s particular target is Alfred Kazin’s article, “The Wound That Will Not Heal,” in The New Republic (August 25, 1986).

↩ -

20

E.H. Carr, The Comintern and the Spanish Civil War (Pantheon, 1984), p. 31.

↩ -

21

See Thomas, pp. 821, 848.

↩ -

22

December 27, 1986.

↩ -

23

The Comintern and the Spanish Civil War, p. 99.

↩ -

24

See also the case of Keith Scott-Watson in Cunningham, p. 323.

↩ -

25

For later, official occasions, such as veterans’ reunions, for example, a cleaned-up version was concocted; its first verse runs:

↩ -

26

For a full account of Spender’s friend and his attempts to get him out of Spain, see Spender’s autobiographical World Within World (Harcourt Brace, 1951) (references under the heading “Jimmy Younger” in the index). The young man was eventually sent back to England.

↩ -

27

Cyril Connolly, on the other hand, found the book “short, modest, and readable an admirable account of the sensations of fighting, a true picture of what war feels like” (Cunningham, p. 19).

↩ -

28

Thomas, pp. 455–456.

↩ -

29

In “Romance de la Guardia Civil,” one of the most famous poems in his collection, Romancero Gitano, the Guardia Civil are credited with “a patent-leather soul” (alma de charol), which may be a sarcastic allusion to their description as “the soul of Spain” by General Sanjurjo, their commander under the monarchy.

↩ -

30

See Ian Gibson, The Death of Lorca (London: W.H. Allen, 1973), chapter 4, “García Lorca and the Popular Front.”

↩ -

31

Just before leaving for Granada in July he said, speaking of a poet who had dedicated himself entirely to politics, “I shall never be a politician. I am a revolutionary, because there is no real poet who is not a revolutionary . But I shall never be a politician, never!” (“Yo nunca seré politico. Yo soy revolucionario, porque no hay verdadero poeta que no sea revoluncionario . Pero politico no lo seré nunca, nunca!“) José Luis Cano, García Lorca: Biografia illustrada (Barcelona: Ediciones Destino, 1962), p. 124.

↩ -

32

“Muera la inteligencia! Viva la muerte!” The last three words are the battle cry of the foreign legion, of which Franco was once commander.

↩ -

33

Preface to L’Espagne Libre, cited in Writers in Arms by Frederick R. Benson (New York University Press, 1967), p. 302.

↩