In response to:

Reagan's Junta from the January 29, 1987 issue

To the Editors:

I have no disagreements with the contemporary portion of Theodore Draper’s article on the Reagan junta [NYR, January 29], but it contains a few historical errors that respect for the author leads me to wish to clean up:

1) The locus of serious opposition to an independent CIA was not Byrnes, who was out of the country for about two thirds of his tenure as Secretary of State, but Dean Acheson, who wrote to Truman that “as set up neither he, the National Security Council, nor anyone else would be in a position to know what it was doing or control it.” The notion of a covert operations branch, incidentally, was George Kennan’s, though later he had the grace to disown it.

2) To say that the job of national security adviser first became significant when Bundy signed on with Kennedy grievously under-estimates Gordon Gray and Robert Cutler, both first-rate men, who served Eisenhower as Special Assistant for National Security Affairs.

3) It’s multiply unfair to make fun of Kissinger for saying that Rogers exalted the NSC by his weakness at State and to accept Schlesinger’s insistence that Rusk lost out to Bundy because his views were “a mystery” to the White House. Having at one time or another met and talked with all five of these (as I’m sure Draper has, too), I feel pretty confident that Kissinger slowly, deviously, with feline deliberation, cut out Rogers, while Schlesinger simply refused to believe that Rusk and Kennedy shared attitudes. The fact is that Rusk spoke with Kennedy every day. Kennedy didn’t like the State Department much, and to the extent that Rusk sheltered his department the President was impatient, but Bundy’s staff of thirteen (run, as Rostow’s was, on the principle that there were no “divisions,” that nobody reported to anyone expect Bundy himself) certainly could not have superseded State, and did not try.

Martin Mayer

New York City

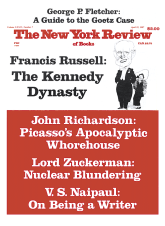

This Issue

April 23, 1987