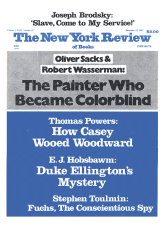

Of the great figures in twentieth-century culture, Edward Kennedy Ellington is one of the most mysterious. On the evidence of James Lincoln Collier’s excellent book, he must also be one of the least likable—cold to his son, ruthless in his dealings with women, and unscrupulous in his use of the work of other musicians. But there can be no denying the extraordinary fascination he plainly exercised over the people he mistreated and was loyal to at the same time, including those who allowed him to establish power over them, i.e., most of his colleagues and lovers.

There was nothing blatant about what must strike impartial observers as his appalling behavior. He was the opposite of the short-fused brawlers who briefly joined so many bands of his time, including his own, though his habit of stealing his musicians’ tunes and, occasionally, their women, must have put a strain on even the more placid among them. However, the only people who actually took a knife or a gun to him, so far as the record shows, were legal or defacto wives, who had more than adequate provocation.

In fact, nothing was obvious about Duke Ellington the man, except the mask he invariably wore in public and behind which his personality became invisible: that of a handsome, debonair, and seductive man about town, whose verbal communications with his public, and very likely with the startlingly large numbers of his female conquests, consisted of vapid phrases of flattery and endearment (“I love you madly”). The autobiography he wrote shortly before his death, Music is My Mistress,1 is a singularly uninformative document as well as a mistitled one. For while he probably despised and tried to subjugate his lovers, indeed all women except his mother and sister, both of whom he idealized and regarded as asexual—at least this is the view of his humiliated son2—his relationship to music was entirely different. Even so, music was not his mistress in the original sense of someone exercising dominion. Ellington liked to keep control.

Here, in fact, lies the heart of the mystery that James Lincoln Collier has tried to elucidate in his book. For Ellington, who has been called, with Charles Ives, the most important figure in American music,3 utterly fails to conform to the criteria of the conventional idea of “the artist,” just as his improvised productions fail to conform to the conventional view of “the work of art.” As it happens, unlike most of his jazz contemporaries, Ellington saw himself as an “artist” in this sense and took to composing “works” for the concert hall, where they were periodically performed. In the black middle-class milieu of the Ellingtons, which Collier rightly insists was important, the conception of the “great artist” was familiar, whereas it was meaningless to someone like Louis Armstrong, who came from a less self-conscious and entirely unbourgeois world.

When Ellington, on his triumphant visit to England in 1933, discovered that for British intellectuals he was not just a bandleader but an artist like Ravel or Delius, he took to the role of “composer” as he conceived it. However, hardly anyone claims that his reputation rests on the thirty-odd ill-organized mini-suites of program music, and still less on the “sacred concerts” to which he devoted much of his final years. As an orthodox composer, Ellington simply does not rate highly.

And yet there is no doubt that the corpus of his work in jazz, which, in Collier’s words, “includes hundreds of complete compositions, many of them almost flawless,” is one of the major accomplishments in music—any American music—of his era (1899–1974). And that but for Ellington this music would not exist, even though almost every page of Collier’s admiring but demystifying book bears witness to his musical deficiencies. Ellington was a good but not brilliant pianist. He lacked both a technical knowledge of music and the self-discipline to acquire it. He had trouble reading sheet music, let alone more elaborate scores. After 1939 he relied heavily for arrangements and musical advice on Billy Strayhorn, who acted as his alter ego in running the band and who became something like an adopted son. The musically trained and immensely sophisticated Strayhorn was better able to judge from a score how the music would sound.

Apart from some informal tips in the 1920s from formally trained black musical professionals like Will Vodery, Ziegfeld’s musical director, he learned little except by a process of trying it out in practice. He was too lazy, and perhaps not sufficiently intellectual, to read much, nor did he listen intently to other people’s music. He did not even, if Collier is to be believed, make any special efforts to find the right kind of musicians for his band, but accepted the first vaguely suitable ones to fill vacancies; though this does not account for the majestic brass and reed lineups of the Ellington band between the later Twenties and early Forties. He was certainly not a great songwriter, if we follow Collier’s demonstration that “of all the songs on which Ellington’s reputation as a songwriter—and his ASCAP royalties as well—is based, only ‘Solitude’ appears to have been entirely his work. For the rest he was at best a collaborator, at worst merely the arranger of a band version of the tune.” And at least one of his sidemen told him, at a characteristic moment of mutual irritation: “I don’t consider you a composer. You are a compiler.”

Advertisement

Last, and perhaps most damaging of all, is Collier’s justified observation that he neither had the talent, the “raw natural gift” of other great jazz musicians, nor was “drawn, indeed driven, to [jazz] by an intense feeling for the music itself.” Unlike many other great jazz musicians, he showed little promise until he was nearly thirty, and he did not start doing his best work until he was forty.

Here lies the chief interest of Collier’s book. In broad outline his judgments are not new. It has long been accepted that Ellington was essentially an improvising musician whose “instrument was a whole band,” and that he could not even think about his music except through the particular voices of its members. That he was musically short-winded and therefore incapable of developing a musical idea at length was always obvious, but conversely it was already known in 1933 that no other composer, classical or otherwise, could beat him over the distance of a 78-rpm record—i.e., three minutes. He has been called by a critic of both jazz and classical music “art’s major miniaturist.”4 Collier’s comments on particular works and phases of the Ellington oeuvre are, as usual, knowledgeable, perceptive, and illuminating, but his general judgment could hardly differ from what may be regarded as the general consensus.

Only through jazz could a man of Ellington’s evident limitations have produced a significant contribution to twentieth-century music. Only a black American, and probably a black middle-class American of Ellington’s generation, would have sought to do so as a bandleader. Only a person of Ellington’s unusual character would have actually achieved this result. The merit of Collier’s book lies in showing what the music owes to the man, but its novelty is to see the man as formed by his social and musical milieu.

The peculiarities of Ellington’s personality have often been described with varying degrees of indulgence. He saw himself, with total and unforced conviction, as “uniquely gifted by God, uniquely guided through life by some mysterious light, uniquely directed by the Divine to make certain decisions at certain points in his life,” and consequently entitled to total power. The critic Alexander Coleman tried to sum up Ellington’s inner thoughts as follows: “I must be able to give and to take away. I command the world because I am ever lucky, careful beyond compare, the slyest fox among all the foxes of this world.”5

This is substantially also Collier’s reading of the man, though the present book insists less than it might on the imperatives of street-smart survival and success that the Duke—the name was given to him early in life—acquired as a smooth young black hustler: the deviousness, the refusal to give anything about himself away, the power strategies of manipulation, the godfather-like insistence on “commanding respect.” In this regard Mercer Ellington’s memoir of life with his father may usefully supplement Collier’s book.

In short Ellington, as he himself recognized,6 was a spoiled child who succeeded in maintaining something of the infant’s sense of omnipotence throughout life. In Washington, DC, his father worked his way up from coachman to butler in the service of Dr. M.F. Cuthburt, “reputedly a society doctor who tended Morgenthaus and Du Ponts,” according to Collier. From this family background and from the relatively large number of politically sheltered or college-educated blacks he knew in his parents’ Washington milieu, he acquired self-respect, self-assurance, and strong pride in his race—and a sense of superiority within it. “I don’t know how many castes of Negroes there were in the city at that time,” he once said, “but I do know that if you decided to mix carelessly with another you would be told that one just did not do that sort of thing.” He preferred not to have a racially mixed band even when this was possible. The charisma that surrounded him derived largely from the consequent, and very striking, air of being a grand seigneur who expected to be deferred to, and this impression was reinforced by charm, good looks, and an indefinable magnetic quality.

Advertisement

However, the spoiled child began as an idle and ignorant failure at school, looking for a good time, who never acquired the knack of learning, hard work, or self-discipline, yet never abandoned his sense of status or his ambition. Music, which he seems to have seen originally merely as an adjunct to having a good time, became an obvious as well as an easy way of earning a living, given the enormous demand of the jazz age, and the position of blacks in the dance bands, which was still strong, in spite of the influx of whites. If educated and college-trained blacks made their way as musicians—often becoming bandleaders or arrangers, as did Fletcher Henderson and Don Redman—it was even more natural for a middle-class ne’er-do-well without qualifications to do so, especially one who had recently been pressured into marriage. In the early 1920s good money was to be made in music, probably more readily than by commercial art, for which the young Ellington seems to have shown some gift.

It was Ellington’s good luck that he entered jazz at the moment when the music was discovering itself, and he was able to discover himself as he grew into it. There is no sign that he particularly wanted to compose, until he formed a partnership with Irving Mills, who, as a music publisher, knew the financial payoff of songs in the world of show business. There is no sign that Ellington wanted to be more than a very successful bandleader.

His band moved from the rough-and-ready syncopated music played by an army of nondescript young groups into “hot” jazz in the middle Twenties, because that was the general trend. Indeed the typical Ellington style may well have been worked out for commercial reasons by means of the “jungle music” that fitted in with the expectations of the Cotton Club clientele. “During one period at the Cotton Club,” Ellington said, “much attention was paid to acts with an African setting, and to accompany these we developed what was termed a ‘jungle style’ jazz.” This had the advantage both of building on the talents of some valued members of the band and of providing the band with an immediately recognizable “sound” or trademark.

Collier also argues that the size and instrumentation of the band grew, because Ellington’s competitors had more brass than he. The models for the big band were white. The arranged music they used was built around what Collier calls a “saxophone choir,” a coordinated reed section pioneered by Art Hickman and Ferde Grofé around 1914 and developed by Grofé and the “King of Jazz” Paul Whiteman in the 1920s. Fletcher Henderson and Don Redman created a black version by means of a complex interplay between soloists and band sections.

Ellington thus became a “composer” because the future of successful bands in the 1920s lay not with freewheeling small groups of blowers but with larger bands playing arranged music. He was in no position to imitate Henderson, whom he admired and from whom, Collier argues, he took over the “system of punctuating, answering, supporting everything with something,” because he was incapable of writing complex music and his men could not read complex orchestration. On the other hand the combination of jazz rhythms with harmonic devices taken from or similar to those of classical music, which Whiteman had pioneered, was easier to follow, and came naturally to a man who lived and breathed the atmosphere of New York show business, and, in fact, did not much like being called a jazz musician. As Collier rightly points out, the real triumph of “symphonic jazz” is not Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue (commissioned by Whiteman) but the band music of Duke Ellington.

Once Ellington found himself responsible for his own band’s repertoire, he was forced to discover himself as a musician. His personal method of creating compositions is well described by Collier:

He would begin by bringing into the recording studio or rehearsal hall a few musical ideas—scraps of melodies, harmonies, and chord sequences usually clothed in the sound of particular instrumentalists in the band. On the spot he would sit down at the piano and quickly rough out a section—four, eight, sixteen bars. The band would play it; Duke would repeat it; the band would play it again until everybody got it. Years later, the pianist Jimmy Jones said: “What he does is like a chain reaction. Here’s a section, here’s a section and here’s another and, in between, he begins putting in the connecting links—the amazing thing about Ellington is that he can think so fast on the spot and create so quickly.” Along the way, members of the band would make suggestions…. As a piece was developing, it would frequently be up to the men in the sections to work out the harmonies, usually from chords Duke would supply. When the trombonist Lawrence Brown came into the band…to make a third trombone, he was expected to manufacture for himself a third part to everything. “I had to compose my own parts…you just went along and whatever you heard was missing, that’s where you were.”

It is obvious that Ellington brought something to this mode of music making beyond his usual disinclination for planing and preparation. He brought a natural and growing fascination for the mixing of different sounds and timbres, a growing taste for pushing harmony to the edge of dissonance, a tendency to break the rules, and a great deal of confidence in his unorthodoxies if they “sounded right” to him. He also brought a tonal sense that is usually compared—by Collier also—to a painter’s colors, but is better thought of as a feeling for show-business effects. Ellington, an unabashed composer of program music, seems not to have thought in colors, which occur hardly at all in the titles of his records (except for the nonpictorial “black” and “blue”), but to have drawn on “a sensory experience, a physical memory,” as in “Harlem Airshaft,” “Daybreak Express”; a mood, as in “Mood Indigo” or “Solitude”; or sentimental stories, like those preferred by traditional choreographers, as in “Black and Tan Fantasy” or many of his longer pieces.

None of this would have amounted to much except in and through a group of creative musicians with independent personalities and unmistakable voices: in short, except in jazz. Unquestionably every piece of Ellington’s music was or is unmistakably the Duke’s, whatever the composition of his band at any moment. Indeed he achieved the same, or analogous, effects through very different combinations of players, even though the band benefited from the long presence of certain quintessential Ellington voices: Cootie Williams, Johnny Hodges, Joe Nanton, Barney Bigard, Harry Carney. (But they developed their style because of what the Duke heard in them.) Moreover, it is undeniable that the musical impressionism that reminded classically educated listeners of Debussy, and the consistently brilliant form of the band’s three-minute recorded pieces—beyond that length they tended to sag or fall apart—are Ellington’s alone.

Nevertheless, his music is important above all because of the way it was made. Duke, the devious manipulator, knew that each musician in the band had to make the music his own. He might do so by being left deliberately without instructions, discovering on his own what Ellington had intended him to—as Cootie Williams was made to see himself as the successor to Bubber Miley’s “growling” trumpet. Or he might be needled by Duke’s deliberate insults into showing what he could really do. There was a method behind the apparently chaotic indiscipline of the band.

Conversely, Ellington was nourished by his musicians, not only because he drew on their ideas and tunes but because their voices were what gave him his own. He was, of course, lucky in his time. Being mostly untrained as well as highly competitive, players developed individual voices, which made possible the most exciting and original combinations. Collier and just about everyone else agrees that the discovery of one such voice, Bubber Miley’s, began the transformation of the Ellington band, and enabled Duke to form those endlessly varied liaisons between the rough and the smooth, the raw and the cooked, which are among his characteristics. It was lucky that the masters of the new hot jazz so often came from New Orleans—Sidney Bechet himself briefly joined the band before it officially became Ellington’s. This almost certainly gave Ellington the taste for mellow and sinuous reeds, the sounds of the saxophonist Johnny Hodges and the clarinetist Barney Bigard.

But Ellington’s dependence on his musicians is most convincingly demonstrated by the fact that he kept the band going to the end of his life although it lost money. Whether with better management it could have paid for itself is unclear, but there is no doubt that Duke poured his own royalties into keeping it on the road. It was his voice. Ellington showed no interest in making or keeping scores of his works, not because he did not have their sound and shape in his mind but because his numbers had no meaning for him except as played, and, as in all jazz, they varied with the players, the occasion, and the mood. There could be no such thing as a definitive version, only a preferred but provisional one. Constant Lambert, and early classical admirer, was wrong in arguing that the record was Ellington’s equivalent for the straight composer’s score.7

It is evident that works created in this manner do not fit into the conventional category of the “artist” as the individual creator and only begetter, but of course this conventional pattern has never been applicable to the necessarily cooperative or collective forms of creation that fill our stages and screens, and are more characteristic of the twentieth-century arts than the individual in his studio or at his desk. The problem of situating Ellington as an “artist” is in principle no different from that of describing great choreographers, directors, or others who impress their character as individuals on team products. It is merely rather unusual in musical composition.

But this undoubtedly raises serious questions about the accepted definition or description of art and artistic creation. Patently the term “composer” fits Ellington as badly as the term “author” fits the Hollywood directors to whom it was applied by French critics with the national penchant for bourgeois and Cartesian reductionism. But Ellington produced cooperative works of serious art that were also his own, just as film and stage directors can, and unlike the megalomaniacs he knew himself to be engaged in a genuinely collective creation.

Collier asks such questions, but is sidetracked by his understandable conviction that Ellington allowed his talents to be diverted from what he did best into “music in emulation of models from the past, which in many cases he did not really understand,” and which was not very good. Whether this “drew him away from developing the form he was at home with” is less certain. After all, by this book’s estimate, he produced upwards of 120 hours of recorded jazz, which is a large enough corpus for most composers, and he developed and innovated to the end of his life. If he produced fewer masterpieces after the age of fifty, the pull of Carnegie Hall is less to blame than the business troubles afflicting his instrument, the big band.

All the same, Ellington will live through music like “Ko-Ko” and not through compositions like the Liberian Suite. But Collier is surely wrong to contrast jazz, as a sort of Gebrauchsmusik “to accompany dancing, to support singers or dancers, or to excite and entertain audiences,” with “art as a special practice with its own principles existing in the abstract, apart from an audience,” and not “created out of a wish to act directly and immediately on the real feelings of people.” Whatever the relation of the accepted conventional arts to the public, which has undoubtedly been a difficult one for avant-garde artists since the beginning of this century, this oversimplifies the relation of jazz musicians to their audience, even if we leave aside the musicians who, since the birth of be-bop, have defied the audience to follow them.

For while it is quite true that Ellington’s finest work was created for cabarets and ballrooms, for the purposes of much of the audience schlock music would have done just as well or better; and in fact the same audiences were content with third-rate bands. Like most jazz organizations of its generation, the Ellington band earned its living playing dances, but did not play for the dancers. The band members played for each other. Undoubtedly their ideal audience accepted their kind of music and was excited by it, but above all it did not get in the way.

The present reviewer, at the age of sixteen, lost his heart for good to the Ellington band at its most imperial, playing what was called a “breakfast dance” in a suburban London ballroom to an uncomprehending audience entirely irrelevant to it, except that a swaying mass of dancers was what the band was used to seeing in front of them. Those who have never heard Ellington playing a dance or, even better, a supper room of sophisticated night people where the real applause consisted in the falling silent of table conversations, cannot know what the greatest band in the history of jazz was really like, playing at ease in its own environment.

On the other hand the people who expected Ellington to “act directly and immediately on the real feelings” did get in the way. In his later years most Americans and all foreigners heard Ellington live only on concert tours. The hushed or applauding halls full of fans waiting for the revelation rarely brought out the best in the band. They brought out the Ellington who knew that enough honking (mostly by Paul Gonsalves) would bring the house down.

Nor is it sufficient to say, as Collier does, “When jazz becomes confounded with art, passion flies out and pretension flies in.” The reason why jazz is important is not that it is passionate and unpretentious. So is most romantic fiction. It is and that, unlike the art Collier dislikes, “millions of people care about it.” It is and has always been a minority art, even by the standards of classical music and serious literature, let alone the real public of millions. It is certainly not a mass art in the US, where New York jazz clubs (like British theater managers) count on the tourist trade as well as the local jazz audience.

Jazz is important in the history of the modern arts because it developed an alternative way of creating art to that of the high-culture avant-garde, whose exhaustion has left so much of the conventional “serious” arts as adjuncts to university teaching programs, speculative capital investment, or philanthropy. That is why the tendency of jazz to turn itself into yet another avant-garde is to be deplored.

More than any other person, Ellington represented this ability of jazz to turn people who are unconcerned with “culture” and pursuing their passions, ambitions, and interests in their own way, into creators of serious and, on a small scale, of great art. He demonstrated this both through his own evolution into a composer and by the integrated works of art he created with his band; a band containing fewer utterly brilliant individual talents than other bands—until the late 1930s perhaps only one, Hodges—but in which extraordinary individual performance was the foundation of collective achievement. There is no other flow of musical creation by a collective to compare with it. Certainly he, and they, acted directly and immediately on the feelings of listeners, but this itself does not explain why, as Collier notes, their music was so much more complex than that of other jazz groups. In short, the author is at times tempted into a populist theory of the arts, by which the artist not only “rejoices to concur with the common reader” (to use Dr. Johnson’s phrase) but takes the common reader’s preferences as a guide. That the theory is inadequate is shown, among other examples, by comparing the American to the German phases of the careers of both George Grosz and Kurt Weill.

However, Collier is entirely right in the belief that the great achievements of jazz, of which Ellington’s music is in some ways the most impressive, grew in a soil quite different from that which produced high art. It was a music of professional entertainers of modest expectations, made in the community of night people with folk roots. It was not supposed to be “art” like chamber music; it did not benefit by being treated as “art” and it tended to get as lost as the high arts when its practitioners turned themselves into yet another avant-garde. Its major contribution to music was made in a social setting that no longer exists. It is difficult to imagine that a great musician of the future will be able to say, like one of Ellington’s major soloists: “All I wanted to be was a successful pimp, and then I found I could make it on the horn.”

Today’s jazz, played largely by educated musicians, often with classical training, essentially for a listening public, by a generation whose links with the blues are largely mediated through rock and musically impoverished gospel sounds, will have to find another way, if it can, to make a mark as great as the jazz of those who grew up in the first half of this century. But all of its players, without exception, will continue to listen to the records of Ellington, about whom Collier has written the best book we have: spare, lucid, perceptive about the man, good criticism, and good history.

This Issue

November 19, 1987

-

1

Doubleday, 1973.

↩ -

2

Mercer Ellington with Stanley Dance, Duke Ellington in Person (Houghton Mifflin, 1978). In Mercer’s account Duke Ellington was kind to him so long as he was willing to do his bidding and help him with the band. When the son tried to strike out on his own as a musician, the Duke, he writes, did everything he could to discourage him.

↩ -

3

Martin Williams, The Jazz Tradition, new and revised edition (Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 102.

↩ -

4

Max Harrison, A Jazz Retrospect (Taplinger, 1976), p. 128.

↩ -

5

Alexander Coleman, “The Duke and His Only Son” (New Boston Review, December 1978).

↩ -

6

Music is My Mistress, p. x.

↩ -

7

Surprisingly, Collier does not quite avoid the same pitfall in his praise of Ellington’s three-minute pieces. The 78-rpm record, which provides us with so many of his surviving masterpieces, did not determine the structure of Ellington’s compositions, but only that of the music produced for the recording studio, as the informal recording of his work in ballrooms demonstrates.

↩