The judges of literary prizes probably feel the need for originality almost as strongly as the writers whom they assess. In a year that produced major new works by Philip Roth and Toni Morrison, a notable collection of stories by Richard Ford, and a favorably reviewed best-seller by Gail Godwin, the judges of the National Book Award for Fiction went well out of their way to avoid the obvious and instead bestowed their wreath upon a novel that received some attention when it appeared but had not, so far as I know, attracted much of a following in the subsequent months. The discovery of an almost unknown work of great merit would indeed be a glorious thing—and a deserved rebuke to those editors and reviewers who had failed to do it timely justice. Is such the case with Paco’s Story, a second novel by Larry Heinemann which has as its subject the Vietnam War and its consequences for one of the “grunts” who served in it?

The novel begins by proclaiming somewhat defensively that “This ain’t no war story.”

War stories are out—one, two, three, and a heave-ho, into the lake you go with all the other alewife scuz and foamy harbor scum. But isn’t it a pity. All those crinkly, soggy sorts of laid-by tellings crowded together as thick and pitiful as street cobbles, floating mushy bellies up, like so much moldy shag rugs (dead as rusty-ass doornails and smelling so peculiar and un-Christian). Just isn’t it a pity, because here and there and yonder among the corpses are some prize-winning, leg-pulling daisies—some real pop-in-the-oven muffins, so to speak, some real softly lobbed, easy-out line drives.

But that’s the way of the world, or so the fairy tales go. The people with the purse strings and apron springs gripped in their hot and soft little hands denounce war stories—with perfect diction and practiced gestures—a geek-monster species of evil-ugly rumor.

The above passage is worth quoting to illustrate not only the novel’s haranguing tone but the metaphoric oddities to which its narrative voice is prone. The voice, we gradually learn, is a collective one, assigned to the dead men of Alpha Company, which, except for one survivor, was wiped out by a nighttime Vietcong assault on Fire Base Harriette.

This ghostly guide constantly exhorts and chides the reader on behalf of that survivor, Paco Sullivan, who for two days lies hideously wounded in the muck and the hot sun, covered with flies, maggots, and gnats, before being discovered by a medic from Bravo Company (who is permanently traumatized by the horror of Paco’s condition and in later life drunkenly tells the story night after night). Transported by helicopter to a base hospital, Paco, despite his lacerated, splintered, and shattered state and despite the stitches in his penis, is able, a few nights later, to enjoy the sexual ministrations of a compassionate nurse.

Back in the States, Paco, who is apparently without family and (unaccountably) without a veteran’s pension, arrives penniless in the small, mid-American town of Boone. There, after encountering rejection and ridicule on the part of local rednecks, he eventually gets a job as a dishwasher in a diner called the Texas Lunch and settles into a room in a shabby hotel across the street. The remainder of the novel is devoted to an account of Paco’s isolated and pain-ridden existence in Boone, interrupted by long and night-marish flashbacks to the Vietnam War and to detailed scenes of horror and carnage in the Russian Revolution and on Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima; the latter are supplied—somewhat gratuitously—by other residents of the town. Added to Paco’s torments is the sexual teasing inflicted by a heartless young woman who lives in the same hotel.

The most successful parts of the novel are those that instruct us how to do things: how to set booby traps of great variety and ingenuity in the jungle surrounding a fire base—or how to soak, hand wash, rinse, and dry the continuing avalanche of dishes, mugs, glasses, cutlery, pots, and pans in a diner that stays open from six AM to eleven PM six days a week and is too small for a dishwashing machine. Heinemann obviously relishes the processes involved, and he describes them vigorously and convincingly. Less convincing (though they may well be factually accurate) are the war scenes. In his determination to spare us no detail of broken bone or gushing blood or flesh reduced to pulp, Heinemann becomes monotonous; the impact of a bullet fired at close range into a human skull is much the same, after all, whether the victim be a “zip” (Vietcong soldier), a grunt, or a Jap, and its description gains nothing by repetition. The routine obscenities of military speech continually reproduced, the routine “macho” reduction of all young women to poontang, pussy, or bitches, the constantly repeated imagery of stench, mud, shit, scum, grease, and garbage, the straining after bizarre comparisons (“that rainbow, as solid and superb as a Corinthian column”), and above all the hectoring, coercive voice (as if the ghost were saying, “And now, reader, I’m going to make you feel exactly what it’s like to participate in the gang rape and throat-cutting of a Vietcong woman”)—these produce, in combination with the sterotyped characters and the largely undifferentiated dialogue, a fatigue like that resulting from a prolonged exposure to pornography. In the midst of all this, the character of Paco himself is so rudimentarily conceived that he hardly exists apart from his wretched situation.

Advertisement

In that it tries, in somewhat blatant fashion, to exploit the reader’s most accessible and predictable responses of revulsion, pity, and guilt, Paco’s Story is, I think, essentially a sentimental novel. That it should have been chosen as the best novel of the year suggests that the judges, for whatever reasons, made a sentimental decision of their own.

That Night, a second novel by Alice McDermott, was a runner-up for the same award. Its subject is the love affair between two teen-agers, Rick and Sheryl, and its setting is a lower-middle-class, mostly Catholic, Long Island suburb in the early 1960s; more broadly, it is the story of the neighborhood’s response to the violent termination of the affair as witnessed by a ten-year-old girl who has been following its progress with all of the rapturous curiosity of a child in love with the idea of love. That girl, now grown into wistful adulthood, recounts the events as she remembers them, imagines scenes involving Rick and Sheryl and their families which she did not witness, and comments ruefully on the changes wrought by time on all of the principals and bystanders, including herself. The result is a pleasant and readable piece of bittersweet Americana, scrupulously detailed and faithful to the spirit of its time and place.

Alice McDermott begins her novel at its most dramatic moment, when Rick, accompanied by his black-jacketed, chain-carrying friends, stands on the short lawn before Sheryl’s house and—“with his knees bent, his fists driven into his thighs”—bellows her name. Unknown to him, Sheryl is pregnant, and her shamed mother and grandmother have shipped her off to relatives in Ohio, where, in accordance with the code of her class and religion, she is to bear her baby and give it up for adoption by a good Catholic family; she is never to see Rick again. All that Rick knows is that Sheryl has not answered his increasingly frantic telephone calls and that her mother has answered them in a frustratingly evasive way. The narrator remembers that, hearing that heart-broken cry, her own “ten-year-old heart was stopped by the beauty of it all.”

Meanwhile the entire neighborhood has gathered outside on that early summer night. The fathers are armed with baseball bats and snow shovels to repel the invasion of “hoods,” who, before pulling up in front of Sheryl’s house, have slowly and menacingly driven though the neighborhood a number of times; the mothers and children are looking on in various states of excitement and alarm. When Rick pulls Sheryl’s mother from her house, the men rush to her rescue and a melee ensues—chains against bats and shovels—that is ended by the arrival of the police. No one is seriously hurt, but for days afterward the fathers, who, unlike their wives and children, are not given to easy socializing within the neighborhood, meet to display their bruises and gashes and to boast about what they will do to the hoods if they ever come back. The narrator apostrophizes them:

Our fathers. They were still dark-haired then, and handsome. Their bruised arms were still strong under their rolled shirt sleeves, their chests still broad under their T-shirts. They had fought wars and come home to love their wives and sire their children; they had laid out fifteen thousand dollars to shelter them. They had grown housebound and too cautious,…but now, heady with the taste of their own blood,…they were ready to take up this new challenge, were ready to save us, their daughters, from the part of love that was painful and tragic and violent, from all that we had already, even then, set our hearts on.

From this point the novel continues to deal with the aftermath of the invasion and follows Sheryl into exile in Ohio. At regular intervals the narrator interrupts her ongoing story to retrace the relationship between the two lovers. Both come from seriously disturbed situations at home. Rick, we learn, is the son of a failed doctor and a mentally ill, often suicidal mother; he does badly in school and hangs out with a tough gang of friends. Sheryl has been left raw and bleeding by the recent death of her young father, who had suffered a heart attack while driving to work. In That Night’s most moving episode, she is driven home by the high school principal, who breaks the news to her, and arrives at the very moment that a policeman drives up in her father’s car, returning it to the family. Convinced that there has been a mistake and that her father is alive, Sheryl “pushed wildly at the car door and then ran up the steps to her house. She seemed to be laughing and the women all up and down the block could hear her call to her father as she entered.” At the time she takes up with Rick she is living at home with her bereaved, embittered mother and her Polish-speaking grandmother and longs for a love to replace her father’s loss. There is a defiant edge to her grief.

Advertisement

Here is the way she looks:

She was skinny, not very tall, with thin taffy-colored hair and light brown eyes…. Her mouth was small and seemed to hang a little too low in her round flat face. She wore pancake makeup and black eyeliner that itself was sometimes lined with white. She dressed as all the girls who went with hoods had dressed. To school, she wore tight skirts and thin, usually sleeveless sweaters made of some material like Banlon or rayon and meant to show off both her bra straps and her small breasts. She wore bangle bracelets and, later, Rick’s silver ID bracelet and a delicate gold “slave chain” on her ankle, under her stocking.

Neither the story, the observations of character, nor the descriptions are in any way remarkable; the prose, while lucid, is hardly distinctive. Still, Alice McDermott deals honestly with her materials and does not try to wring from them any more poignancy or pathos than they warrant. Rick and Sheryl are ordinary kids, not a re-embodied Romeo and Juliet, and it is their ordinariness—and that of their suburban town—that are so affectionately re-created by the narrator. McDermott can be funny too, as in her account of the Carpenter family who live chiefly in the finished basement of their house—a basement equipped with a bathroom and a kitchenette—because the rest of the house, with its white and gold living room and a carpet that feels “like fur laid over clouds,” is “too beautiful to bear.” The forward glances to the present, which allow us to see the decline of the neighborhood and the fear of crime that has replaced the old sense of security, are handled with considerable tact and a minimum of nostalgia. The final glimpse the author allows us of the adult Rick and his dejected family is, in its understated way, devastating.

That Night is, then, a small, decent work that succeeds within its limits. That it should have been nominated as one of the five best novels of the year must, I imagine, be nearly as surprising to its author as it is to this reviewer. No such nominations are likely to be in store for Cigarettes, a cool and elegant work of fictional art that keeps its readers at a very unsentimental distance. It is the fourth novel—and the first since 1975—by Harry Mathews, an American writer who has spent much of his life in Paris; his earlier books—especially The Conversions (1962) and Tlooth (1966)—have gained for him a quiet, underground reputation as a skilled deviser of elaborate and difficult literary games. While Cigarettes also has its tricky aspects, it is relatively accessible—and can yield much enjoyment to an attentive reader.

The first and final pages of Cigarettes are told in the first person by a narrator whose identity we do not learn (though at a certain point we may guess) until the end of the novel. Otherwise, its complex events are related in a third-person voice that is almost Olympian in its knowing-ness and detachment. The novel is divided into fifteen chapters, each headed by the names of the two principal characters involved: Allan and Elizabeth, Oliver and Elizabeth, Oliver and Pauline, Owen and Phoebe: I, Owen and Phoebe: II, etc. The setting alternates between Saratoga Springs and New York City, and the dates (also given in the chapter headings) jump from 1963 to 1936 and 1938 and then back to 1962–1963.

Running as a kind of leitmotif throughout the book are the appearances of a beautiful, sexually avid, mysterious, and witty woman named Elizabeth, who is the lover of some of the characters and the “genetrix-muse” of others; though widely scattered and relatively few, her appearances are always memorable, and her influence is pervasive. Elizabeth’s portrait (by a painter named Walter Thrale) and its copy (by Walter’s disciple, Phoebe Lewison), both of which change hands a number of times, serve as a similar subject of interest and contention. We first encounter Elizabeth, who is about fifty, in Saratoga where she is being pursued by Allan Ludlam, a rich insurance broker of sixty married to an even richer woman named Maud. After an evening of gambling at the casino, Allan and Elizabeth go to bed in her hotel, where, the preceding night, Allan had eavesdropped on her lovemaking with someone else.

In love, too, Allan exercised self-control. He took care to please first. Elizabeth preferred abandon—no “mine” or “yours,” certainly no yours and then mine. For Allan, a woman’s pleasure guaranteed his own. It was money in the bank.

Elizabeth nailed him: “I love the things you do to me, but let’s not spend all night paying our dues. It’s you I want.” He started to explain. She laughed: “Look, I like being irresistible, too. Stop running things.”

He agreed to try. Trying only discouraged him more and shriveled his purpose…. In a while he somewhat forgot his predicament; and then when he too was playing she slapped him again, just hard enough to toughen his desire with sportive vindictiveness. He let go, and kept letting go, and as he did so, a high, eerie, familiar wail filled his head. He forgot himself, he forgot everything, except for one offstage, insidious question: Who’s listening tonight?

The opening chapter proceeds in this crisp fashion to its end, by which time Elizabeth moves in with Maud, Allan is exiled to New York, and we learn that Allan—for the sport of it rather than money—has involved himself in a crooked insurance deal involving a crippled race horse.

The second chapter takes us back twenty-seven years to a fashionable racing-season garden party where Elizabeth flirts with the handsome young Oliver Pruell and the next day makes love with him in a Saratoga mud bath. But it would be futile to continue following the action, which is much too complicated, and involves far too many characters and far too many shifts in their relationships to lend itself to summary. The relationships are invariably unhappy: an adoring but manipulative father (Owen) tries to control his daughter’s (Phoebe’s) life, only to have her turn against him in rage and then become seriously ill with a rare thyroid disease; Louisa (Owen’s wife) tries to help her homosexual son (Lewis) and is rejected; Lewis involves himself in a sado-masochistic affair with Morris and is exposed in the tabloids when Morris suddenly dies in a scandalous situation; Owen blackmails Allan to get possession of Walter’s portrait of Elizabeth….

As in an elaborate dance, the characters of Cigarettes step forward, perform their figure, and then step back—and on it goes until the formal but enigmatic pattern is completed, and we are back with the original narrator who has choreographed the whole spectacle. The themes that emerge are at least as numerous as the dancers. I suppose most of them could be summed up under the heading of the Vanity of Human Wishes. But one should not strain too hard after meanings—the pattern is enough. Though sad and painful things occur, the prevailing tone is more wistful than tragic, and there are many wonderfully droll interludes. The narrative voice throughout gives an impression of tight control; much more is told than dramatized, and the reader, while constantly informed and entertained, is not invited to come too close.

Mathews has perfected a witty, supple, and aphoristic style, capable of many effects. Here, for example, is the account of an hallucination experienced by the desperately ill Phoebe:

Phoebe’s grandmother attended her constantly—a presence not disturbing, not reassuring. She had been permanently transformed into a bird. Although large and black, the bird brought to Phoebe’s room a sense not of ominousness but of placid, continuous movement, like the sound of planes regularly landing and taking off at a distant airport. The bird spoke less and less.

The narrator (revealed at last to be the masochistic Lewis) remarks on masculine psychology:

Some males claim to dislike women, others to like them, but all share an original, undying fear. Every man is irrationally and overwhelmingly convinced that woman, having created him, can destroy him as well. Men are all sexual bigots. The distinction between dislike and like only separates those who resist women’s power by attacking them from those who try to exorcise it through adoration and submission. Walter belonged to the adoring class.

And here, finally, is Elizabeth’s response to Maud’s suggestion that they join Mr. Pruell on a sailing yacht from Cape Cod to Mount Desert:

Nothing appealed to her less, said Elizabeth, than cramped quarters amid infinite space.

I could go on, but I hope enough has been given to indicate the flavor of Mr. Mathews’s odd and gratifying novel.

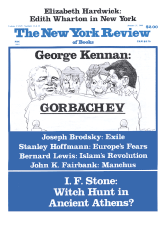

This Issue

January 21, 1988