In response to:

The End of the Affair? from the October 8, 1987 issue

To the Editors:

Psychohistorians of the future may explain to us why so many who favor a peaceful exit from Nicaragua can’t resist kicking the Sandinistas in the shins as they leave. The Sandinistas may deserve many of the kicks, but they certainly don’t deserve those delivered by James Chace in his article, “The End of the Affair?” [NYR, October 8, 1987].

Mr. Chace cites a colloquy between Peter Davis and President Daniel Ortega about freedom, recorded in Davis’s Where is Nicaragua? Mr. Chace says that Ortega “agreed” to the proposition that freedom for the people at large excludes the possibility of freedom for the individual, exclaiming, “Your freedom, sir, is a monster.” If Mr. Chace had read on past this dramatic quote, he would have discovered that Ortega was speaking of “economic freedom,” which in his view had been used by the US-Somoza partnership to exploit, oppress, and impoverish the Nicaraguan people. When it came to freedom of speech and the press, Mr. Davis quotes Ortega as concluding, after justifying war-time censorship, “I don’t like censorship, and I hope it will end soon. Freedom to speak and write is crucial to the revolution.”

Mr. Chace quotes the Americas Watch Report, Human Rights in Nicaragua 1986, as giving a total of over 4,000 “security related” prisoners in Nicaragua. He says caution has to be used about the number of political prisoners in Nicaragua and launches into a discussion of temporary pre-trial detainees and their alleged abuse as causing a difficulty in compiling figures. Thus, despite his disclaimers, he has neatly planted in the mind of the unwary reader the order of magnitude of 4,000 political prisoners, many of whom are abused.

With regard to the number of political prisoners and the 4,000 figure cited from the Americas Watch report, Mr. Chace has once again failed to read on to the end of the paragraph from which he extracted his information. The two sentences following the 4,000 figure in the Americas Watch report are as follows:

We do not offer an estimate as to the number who would be considered “political prisoners” as that term is used in the United States—that is, imprisoned for beliefs, non-violent expression or association—as neither Americas Watch nor anyone else has undertaken the case-by-case investigation needed to make a fair estimate. It was not the practice of the Nicaraguan Government during the period under review to imprison anyone on charges involving beliefs, non-violent expression or association [emphasis mine].

The 4,000 figure includes former National Guardsmen, contras, and contra collaborators. Americas Watch states in its report that it found only two prisoners who fit the definition of “political prisoner,” one of whom had been released by the time the report came out. This doesn’t mean there aren’t others. As Americas Watch says, a case-by-case analysis is needed.

Mr. Chace has every right to bring up the question of the treatment of temporary pretrial detainees. Here the Nicaraguans have earned some severe kicks (although any scrutiny of “white torture” in Nicaragua would raise embarrassing comparisons with the color of torture in some of her US-supported neighbors). But Mr. Chace’s juxtaposing this category of temporary prisoner with the spurious 4,000 figure (which in any case does not include detainees) misleadingly conveys to the unwary reader the impression of some vast, shadowy Gulag.

What are we to make of Mr. Chace’s statement that the Coordinadora ran candidates for parliament and the presidency in the 1984 elections? The Coordinadora, in fact, at the behest of the US Government, chose to boycott the election in the hope of discrediting it, and the US Government gleefully made a great brouhaha about it.

Mr. Chace mentions “considerable harassment of opposition leaders” in the 1984 election. In fact, eight complaints of disruption were filed with the Supreme Electoral Council with respect to the more than 260 rallies conducted by opposition parties in the election. Five of these were substantiated. No injuries or deaths were involved. Someone has suggested that we try to find a French or Italian election with such a record.

The Coordinadora and its candidate, Arturo Cruz, who, as noted above, decided not to run in the election and thus had elected to conduct its activities outside the law’s protection, encountered four incidents, also not involving injuries or deaths. In one of these the Sandinista police protected Cruz from a crowd angered by what it considered his support of the US and the contras who had murdered the loved ones of the assembled people (The Electoral Process in Nicaragua: Domestic and International Influences, Latin American Studies Association, Nov. 19, 1984).

Finally, Mr. Chace predicts a “sad and impoverished country” as Nicaragua’s future. He doesn’t mention that most of the rest of Central America is also sad and impoverished. There was an exciting time when some thought Nicaragua might escape this sad impoverishment. In the first few years of the revolution, the Sandinistas: increased the per capita GNP by 10 percent while per capita GNP of Central America as a whole decreased by 16 percent; decreased the infant mortality rate by one-third (from 113 per thousand live births to 75); decreased illiteracy from 50 percent of the population to 13 percent; launched a health program which was hailed by the World Health Organization as a model for all Third World nations to follow; increased food consumption by 40 percent. This last was accompanied by a great increase in food production, including a 45 percent increase in bean production and a doubling of rice production. Costa Ricans were coming across the border to buy beans and rice (Nicaragua: What Difference Could a Revolution Make?, Joseph Collins).

Advertisement

The high hopes generated in those heady days were stilled as the contra war diverted Nicaragua’s slender resources to defense. It may be that there is no causal connection here and that sad impoverishment is built into Sandinista ideology and methods, while it is just a happenstance in the rest of Central America. But I suspect the Central American elites and the folks in Washington fear it may be the other way around. There may be method in the contra madness. An Oxfam report a couple of years ago declared Nicaragua to be exceptional among the seventy-six nations where Oxfam works in the strength of the Government’s commitment to improving the condition of the people and encouraging their active participation in the development process. The title of the report gives a clue to the method in the madness; it is “The Threat of a Good Example.”

Jane Burnett

New Canaan, Connecticut

James Chace replies:

As I pointed out in my article, it is extremely difficult to give an exact figure on the number of political prisoners in Nicaragua. The figure of approximately 4,000—in fact 3,800—in the Americas Watch report referred to “political prisoners” in “the Latin American usage”—that is, “prisoners convicted of or facing prosecution for politically motivated offenses…or being held in pretrial detention on security-related charges.”

Other sources, which I cited from The Washington Post (May 18, 1986), reported that Tomás Borge, the minister of the interior, claimed there were 10,293 prisoners, of which only 70 percent were jailed for “common crimes.” Vilma Nuñez, the president of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Rights, a government-sponsored group, was quoted by the Post as giving out a figure of about 9,500 prisoners, “including 300 in State Security detention centers, 2,322 former National Guardsmen, and 1,500 to 1,600 other ‘counterrevolutionaries.’ ” According to Lino Hernández, the head of the non-governmental Permanent Commission on Human Rights, as quoted in the Post, “only the figure for the imprisoned National Guardsmen is not in dispute. In addition, he said, there are ‘no fewer than 7,000 political prisoners,’ in a total estimated prison population of about 14,000, including up to 1,500 held in State Security facilities.”

As for the current state of the political parties that took part in the 1984 election, there are now six parties, apart from the Sandinistas (FSLN), represented in the National Assembly: the PSN (Nicaraguan Socialist Party); the PCN (Nicaraguan Communist Party); the MAP-ML (Marxist-Leninist Popular Action Movement); the PCD (Democratic Conservative Party); the PLI (Independent Liberal Party); and the PPSC (Social Christian Popular Party). At the time of the 1984 elections, the Coordinadora, the opposition political coalition that finally refused to participate, was composed of three political parties: the PSCN (Social Christian Party); the PLC (Liberal Constitutional Party), which had earlier split with the PLI; and the PSD (Social Democratic Party). A fourth party, the PCN (Nicaraguan Conservative Party), was a splinter of the old Conservative party and was not officially recognized as a party. The Coordinadora also included two labor unions and the businessmen’s group, COSEP.

Ms. Burnett correctly cites my statement that there was “considerable harassment of opposition leaders” during the 1984 campaign, but then she goes on to talk about the number of complaints filed with the Supreme Electoral Commission. I spoke of harassment, not “injuries or deaths” (Ms. Burnett’s words). My account is supported by the report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States. In their 1983–1984 Annual Report the IACHR wrote:

It should be noted that human rights organizations have alerted the IACHR toward the significant increase in the harassment of various political and union leaders by the security forces…. In addition, the Commission has been able to verify that during the current electoral process, the Sandinista National Liberation Front has intensively used all of the resources made available to it by its holding of state power, which places it in an advantageous position with regard to other contenders. In this regard, the denounced harassment of political and union leaders is unacceptable.

As for the mismanagement of the economy, I suggest that Ms. Burnett read the book I cited by Forrest D. Colburn, Post-Revolutionary Nicaragua, which demonstrates the extent of economic damage inflicted by the Sandinistas’ mismanagement before the full effects of the contras’ war were felt.

Advertisement

With the passing of the December deadline, the Arias plan now goes into its third phase. The Sandinistas have fulfilled many of the provisions of the Guatemala accords by allowing the opposition newspaper La Prensa to reopen and the Catholic radio to rebroadcast, by announcing the release of over 981 political prisoners and allowing greater freedom of assembly. They have still not declared a general amnesty, or lifted the state of emergency under which many political and civil rights are restricted, or extended freedom of the press beyond La Prensa and Radio Católica.

Perhaps most significant was the decision of the Sandinistas to call for indirect talks with the contras, and to ask the regime’s leading critic, Miguel Cardinal Obando y Bravo, to act as a mediator. They have also asked for bilateral talks with the United States to discuss US security concerns, such as the Soviet and Cuban presence in Nicaragua and Managua’s support for leftist insurgencies in the region.

The revelations in December by the Nicaraguan defector Major Roger Miranda Bengoechea, who was a senior Nicaraguan Defense Ministry official, that the Sandinistas intended to support the creation of an 80,000-man army and a 420,000-man militia was largely confirmed by both the defense minister, Umberto Ortega, and by his brother, President Daniel Ortega. President Ortega said in The New York Times (December 16, 1987), “We will probably have a 60,000-to 80,000-man army, but the whole people will always be a reserve force.” The question of further Soviet aid was also raised by both the Ortegas and by Major Miranda; however, Major Miranda admitted that the Soviet Union had never delivered on Managua’s request for a squadron of MIG 21s. It was later reported that Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev mentioned to President Reagan during an eleven-minute private walk around the White House grounds that he was willing to limit arms shipments to Nicaragua to “police weapons.” There apparently was no follow-up by Mr. Reagan, though there ought to be (The Washington Post, December 14 and 16, 1987). These revelations only underscore the need for direct talks by Washington with Managua on matters affecting the security of the region. If such talks led to a signed agreement between Managua and Washington on the levels of military buildup in Nicaragua and neighboring Honduras, the principle of accountability would finally be established. At this writing Washington has responded that it was willing to talk with Nicaragua only as part of a multilateral negotiation with all five Central American states participating. Finally, in mid-January, the five Central American presidents will meet once again to evaluate the plan’s success.

Apparently assuming that the plan will finally falter, administration officials had discussed with the Congress a request for $270 million in lethal and humanitarian aid for the contras for eighteen months starting October 1, 1987. Congress, however, has been willing to appropriate only $8.1 million in nonlethal aid through February 29, 1988. The congressional authorization would also allow the delivery of previously purchased military equipment. But the peace plan continues to have its own momentum despite the administration’s obstructionist tactics. So far at least, Washington has not succeeded in defining for the Central Americans its own conditions for peace in the region.

—December 21, 1987

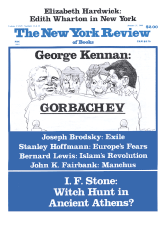

This Issue

January 21, 1988