Go Tell It on the Mountain, its pages heavy with sinners brought low and prayers groaning on the wind, scared me when I read it as a teen-ager. I was afraid that around any corner in the story of how Johnny Grimes, “frog eyes,” came to be saved I ran the risk of exposure. It spoiled my wistful identification with The Catcher in the Rye, which all my friends were soaking up at the time. None of them had read Go Tell It on the Mountain, though, as did everyone else in the late 1960s, they knew what the name James Baldwin stood for. I was left alone with the book, as if it had been the little box at the bottom of the exam form that only I, as a black, was asked to pencil in. I thought I was better than Johnny, sweeping dust from a worn-out rug on his birthday, but I wasn’t sure that the trap of Harlem, 1935, was as long ago and far away as I wanted to believe.

The name James Baldwin had been around the house for as long as I could remember, and meant almost as much as that of Martin Luther King. The Fire Next Time, my parents tell me, had an explosive effect unlike anything else since Native Son or Invisible Man, and in part led to a settling of accounts and an opening of new ones. Some old-timers thought he was too far out, others were jealous of this storefront preacher’s Jamesian overlay—“slimy” was my grandfather’s word—but Baldwin’s prophetic voice was irresistible. It brought an intense moment of unity among Freedom Riders, professionals spawned by the GI Bill, the Blue Vein Circle that considered itself slandered by E. Franklin Frazier’s exposé, Black Bourgeoisie, and the many who did not think Frazier had gone far enough. In retrospect, Baldwin’s cry that blacks were of two minds about integration into a burning house seems hopeless since the power of a minority to threaten a majority with moral collapse depends on how much the majority cares. The climate of the times—perilous sit-ins and voter registration drives, murders and marches, songs of toil and deliverance—had everything to do with the sensation created by The Fire Next Time. Of course in those pre-Selma days no one believed that we’d ever have to walk alone.

Baldwin gave expression to the longings of blacks in exalted prose. He was embraced, in the tradition of Negro Firsterism, even by those who never sat down with a book, as our preeminent literary spokesman, whether he liked it or not. Neither athlete nor entertainer, but nevertheless a star. I do not know why it became fashionable among militants to dismiss him as absent without leave from the struggle, or as too moderate, conciliatory, a honky lover. He was, it seemed, always there, and he arrived on the stage in the apocalyptic mood. He filled my mind as the single enduring image of the black writer, an example to dwell upon beyond admiration or envy.

It helped that he had a genius for titles, for the phrase at once biblical and bluesy. I was drawn without hesitation to Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, and at a time, I must admit, when I was ashamed to request a book from the library that had the word Negro or Black on the spine, as if there were something Baptist and loud about the connection between me and such a text. I didn’t have to be embarrassed to say his name because James Baldwin was more than all right. One day I spotted “An Open Letter to my Sister, Miss Angela Davis,” in this paper. I read it over and over, as if it were a poem—“For, if they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us that night”—and was very moved to find joined the two living souls who, because I looked up to them, relieved my fear that I was an Uncle Tom.

For a long time I thought of my being black as an extracurricular activity. Baldwin’s novels represented time off from the reading list: I took to them as romances, in the privacy of my room. Another Country was the steamiest book I’d ever sneaked off the shelf. There was something illicit in the vulnerability of his black male characters, given the smoky deviations by which his prodigals acted out their torment, and I vaguely expected to uncover in his interracial plots some clue to my own social inhibitions. When no black character appeared in the Paris of Giovanni’s Room, I knew that he had broken the rules.

Until I die there will be moments, moments seeming to rise up out of the ground like Macbeth’s witches, when his face will come before me, that face in all its changes, when the exact timbre of his voice and tricks of his speech will burst my ears, when his smell will overpower my nostrils. Sometimes, in the days which are coming—God grant me the grace to live them—in the glare of the grey morning, sour-mouthed, eyelids raw and red, hair tangled and damp from my stormy sleep, facing, over coffee and cigarette smoke, last night’s impenetrable, meaningless boy who will shortly rise and vanish the smoke, I will see Giovanni again, as he was that night, so vivid, so winning, all of the light of that gloomy tunnel trapped around his head.

He had a way of sometimes signing off at the end of a work—“Istanbul, December 10, 1961″—and that, not the labor of composition, said, to me, that there was indeed a door somewhere to the outside. Wherefore wilt thou run, my son, seeing that thou hast no tidings?

Advertisement

James Baldwin was born into the black church and he came into the world with his subject matter. He was a boy evangelist, a dreamer in school—“I read books like they were some kind of weird food”—a malcontent in the defense plants of New Jersey, then, with the teeth marks still on his throat, an escapee to France, and from these unlikely beginnings he projected a career. “I wanted to prevent myself from becoming merely a Negro, or even, merely a Negro writer.” He held fast to the steady view, to a premise profound in its simplicity: the conditions under which black Americans lived were unnatural. Out of the fundamental distortions of black life he spun the essays in Notes of a Native Son, a work triumphant in the clarity of its paradoxes.

Harlem was central to his journey. He described in celebrated essays and in the stories of Going to Meet the Man not a slum, but a ghetto, an unfathomable valley where wasted sharpies, toil-blasted women, idle old men, and sanctified girls stood corralled. “Only the Lord saw the midnight tears.” He knew about street corners, teen-age pregnancy, and drug addiction, the urban equivalents of the chain gang. Baldwin’s Harlem was a desolate landscape, completely severed from the cultural glories of its past. Though in Nobody Knows My Name he was haunted by the South as the source of his “inescapable identity,” the Old Country remained opaque, erotic in his polemics, almost fable-like in his fiction, and fathers like Deacon Grimes revealed themselves as kinsmen to Bigger Thomas only when restored to the suffocation of the tenements. He wrote out of the black urban experience of his generation. Harlem was not a capital, not even a metaphor for claustrophobia. It was the real thing.

The journey out of Egypt was his great theme—that, and the search for identity, the necessary shedding of spiritual burdens along the road, the white world as the wilderness. The early essays are an unequalled meditation on what it means to be black in America. Baldwin came of age as a writer during the cold war. He spent his youth, unlike Wright or Ellison, not in radical politics, but in religion. The pulpit was always present in his work, and this legacy guided a vivid literary imagination that made for his high style, for his arresting lyricism of despair. The refinement of gut feeling and the bravery of his ambivalence were entirely original. I do not think I am alone when I say that for young blacks Baldwin’s candor about self-hatred was both shocking and liberating. A message slid under the cell door.

He conceived of race relations as a drama of confession and absolution. He asked questions of the future and dared to believe that to hate and fear white people, to despise black people and the black ghetto, gave to the butch and criminal elite an easy victory. If there were no acceptable version of himself as a black man he would have to invent one, and demystify whites in the process. “No one in the world—in the entire world—knows more—knows Americans better or, odd as this may sound, loves them more than the American Negro. This is because he has had to watch you, outwit you, deal with you, and bear you, and sometimes even bleed and die with you, ever since we got here, that is, since both of us, black and white, got here—and this is a wedding.” People, he argued, do not wish to become worse, they want to become better, but don’t know how. Eventually he was made to pay the price for his gamble that they, the motley millions, worried as much about us as we, the new day a-coming, did about them; for his insistence on loaded values like love in an age of dubious cool.

Advertisement

Baldwin once warned us that the second generation has no time to listen to the first, but we were caught up in the long, hot summer and then yonder came the blues in the form of the southern strategy of the Nixon campaign, the beginning of the end. The right made quick business of the revolution, as we liked to call it, because those doomed creatures, white liberals, already had been intimidated, purged, told where to go. On our side of the cameras, ideological patricide became the order of the day, and extra dustbins were conjured up to accommodate the gentlemen who failed the how-black-and-bad-are-you test. Someday someone will assess what damage, if any, was done to Baldwin—and to us—by the attacks on him as an apologist for the Jews.

The denunciation of Baldwin in Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice precipitated a crisis of inspiration. Where are those Sentas of Black Power who ran around the school lockers with this manifesto of extreme violence and vulgarity? Cleaver equated intellectuality with homosexuality and declared them crimes against the people, worse than “baby-rape.” Perhaps, given the bitterness and frustration of those days, the venality of benign neglect, Baldwin would have come to distrust the worth of the intellectual life, the uses of the reflective voice, but I can’t help wondering if he didn’t take Cleaver’s indictment seriously because of the “merciless tribunal” he convened in his own head. The evasive response in No Name in the Street, the capitulation in his saying that Cleaver did what he felt he had to do, caused me to think of him as defenseless, adrift, lacking the blustering, self-protecting ego of the important American writer. In any case, today we know where the dude Cleaver is at. As for Baldwin, the baroque sense of grievance was replaced by sermon, and maybe I’m wrong but I think the change in tone came about because he was forced by his volatile constituents to keep up with events as they saw them. His need to be political, in the popular sense, undermined his literary gift.

“Some escaped the trap, most didn’t. Those who got out always left something of themselves behind.” He often said that he was a commuter, not an expatriate, and maybe the gestures of the engaged writer were part of a larger compulsion to get back home, to honor where he came from, to prove that he had not forgotten. The later novels, If Beale Street Could Talk and Just Above My Head, place emphasis on the black family as refuge, on reconciliation and belonging, but they are as immobile as urns, as if in them he hoped to lay down his burden of being different, the smart black youth who feared his father and wrote his way out of poverty into the bohemian life. “Nothing is ever escaped,” he said early on. But he was not a home boy; he was an elevated extension of ourselves.

It is impossible to read his memoir of Richard Wright without suffering a chill. Baldwin was young and very aware of his own promise, a reminder that before St. Paul de Vence he had his share of crummy rooms. Wright, in exile, sat alone, isolated from other blacks, mocked. “I could not help feeling: Be careful. Time is passing for you, too, and this may be happening to you one day.” Then Wright was gone and Baldwin noted the will in the lesson: “Well, he worked up until the end, died, as I hope to do, in the middle of a sentence, and his work is now an irreducible part of the history of our swift and terrible time.” I thought of this passage after I read The Evidence of Things Not Seen, his report on the Wayne Williams trial in Atlanta, which made it a hard book to face in the first place. The flow of startling insights and connections had dried up. “The auction block is the platform on which I entered the Civilized World. Nothing that has happened since, from South Africa to El Salvador, indicates that the Western world has any real quarrel with slavery.” It was a performance sopra le righe.

One heard exhaustion when he, still a striking apparition, murmured rhymes at audiences during his last appearances around town, and everyone remembered that back in the kingdom of the first person his work had the grace and melancholy of obsolete beauty, like a Palladian dance hall uptown improbably at rest between empty lots.

There’s not a breathing of the com- mon wind

That will forget thee.

Among writers, black or white, he had few peers, among those who bore witness none. He was buried from St. John the Divine as a hero of the folk. The drums sounded and one missed him immediately. Against great odds he lived out the life of a brilliant innocent, and went the luckless distance for us all. The first time I met him I had with me a book that was meant to serve the sad function of showing Manhattan how interesting I thought I was. It was a volume from Leslie Marchand’s edition of Byron’s journals that Mr. Baldwin found himself asked to sign, and sometimes I think his smile as he wrote across the title page said: number got.

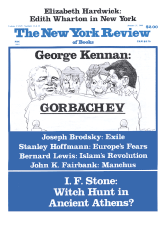

This Issue

January 21, 1988