The very first people whom we consider authors—the minds and voices behind the tribal epics, the Bible and Homer, the Vedas and the sagas—were, it would seem, public performers, for whom publication took the form of recitation, of incantation, of (we might say) lecturing. The circumstances wherein these primal literary works were promulgated are not perfectly clear, nor are all examples of oral literature identical in purpose and texture; but we could risk generalizing that the bard’s function was, in the Horatian formulation, to entertain and to instruct, and that the instruction concerned the great matter of tribal identity. The poet and his songs served as a memory bank, supplying the outlines of the determinative tribal struggles and instances of warrior valor. Who we are, who our heroic fathers were, how we got where we are, why we believe what we believe and act the way we do—the bard illuminates these essential questions, as the firelight flickers and the mead flows and the listeners in their hearts renew their pact with the past. The author, himself, is delivering not his own words but his own version of a story told to him, a story handed down in an evolving form and, at a certain point, fixed into print by the written version of a scribe. The author is not only himself but his predecessors, and simultaneously he is part of the living tribal fabric, the part that voices what all know, or should know, and need to hear again.

The mnemonic function of poetry weakly persists in certain helpful rhymes (“Thirty days hath September,” etc.), and the traditional, even sacred centrality of the bard at the tribal conference lingers in the widely held notion that authors can “speak”—that their vocation includes an ability and a willingness to entertain and instruct, orally, any gathering where the mead flows and ring-gold is exchanged in sufficient quantities. The assumption is flattering but in truth the modernist literary tradition, of which we are all, for lack of another, late and laggard heirs, ill prepares a writer for such a performance. James Joyce evidently had a fine tenor voice and loved to sing, and he also, inspired by enough mead, could kick as high as the lintel of a doorway; but Proust was of a thoroughly retiring and unathletic nature, and murmured mostly to himself. “Authentic art has no use for proclamations, it accomplishes its work in silence,” he wrote, in that long meditation upon the writer’s task which concludes Remembrance of Things Past. “To be altogether true to his spiritual life an artist must remain alone and not be prodigal of himself even to disciples” is another of his strictures. The artist, he repeatedly insists, is not another citizen, a social creature with social duties; he is a solitary explorer, a pure egotist. In a great parenthesis he explains that “when human altruism is not egotistic it is sterile, as for instance in the writer who interrupts his work to visit an unfortunate friend, to accept a public function, or to write propaganda articles.”

In almost the exact middle of Time Regained, Marcel contemplates his task—the huge novel we have at this point almost read through—and quails at a prospect so grand and exalted. He has stumbled upon the uneven paving stones that have recalled Venice to him, has heard the clink of the spoon upon glass that has reminded him of the train journey on which he had observed the steeples of Martinville, has felt the texture of the stiff napkin that has reminded him of Balbec and its beach and ocean; he has tasted the madeleine out of which bloomed all Combray, and sees that these fragments involuntarily recovered from the abyss of Time compose the truth he must deliver:

Beneath these signs there lay something of a quite different kind which I must try to discover, some thought which they translated after the fashion of those hieroglyphic characters which at first one might suppose to represent only material objects. No doubt the process of decipherment was difficult, but only by accomplishing it could one arrive at whatever truth there was to read. For the truths which the intellect apprehends directly in the world of full and unimpeded light have something less profound, less necessary than those which life communicates to us against our will in an impression which is material because it enters us through the senses but yet has a spiritual meaning which is possible for us to extract.

This extraction of meaning, from tactile hieroglyphs, becomes on the next page an underwater groping:

As for the inner book of unknown symbols (symbols carved in relief they might have been, which my attention, as it explored my unconscious, groped for and stumbled against and followed the contours of, like a diver exploring the oceanbed), if I tried to read them no one could help me with any rules, for to read them was an act of creation in which no one can do our work for us or even collaborate with us. How many for this reason turn aside from writing! What tasks do men not take upon themselves in order to evade this task! Every public event, be it the Dreyfus affair, be it the war, furnishes the writer with a fresh excuse for not attempting to decipher this book: he wants to ensure the triumph of justice, he wants to restore the moral unity of the nation, he has no time to think of literature. But these are mere excuses, the truth being that he has not or no longer has genius, that is to say instinct. For instinct dictates our duty and the intellect supplies us with pretexts for evading it. But excuses have no place in art and intentions count for nothing: at every moment the artist has to listen to his instinct, and it is this that makes art the most real of all things, the most austere school of life, the true last judgment.

The religious tone of classic modernism, its austerity and fanaticism, strike us as excessive. Its close imitation of European Catholicism seems puzzling, now that the vessel of Christianity is a century more depleted. Austerity and fanaticism are now entirely given over to the Muslims, who alarm us each night on the news. Virtue and vice alike have been trivialized into news. What do the emanations from the ivory tower count against those from the television transmitting tower? This phrase “ivory tower” was proposed by Flaubert, the first modernist novelist, when he wrote,

Advertisement

Between the crowd and ourself, no bond exists. Alas for the crowd; alas for us, especially. But since the fancy of one individual seems to me just as valid as the appetite of a million men, and can occupy an equal place in the world, we must (regardless of material things and of mankind, which disavows us) live for our vocation, climb up our ivory tower and there, like a bayadere with her perfumes, dwell alone with our dreams.

The artist’s only possible camaraderie, Flaubert elsewhere asserts, can be with other artists. “Mankind hates us: we serve none of its purposes; and we hate it, because it injures us. So let us love one another ‘in Art,’ as mystics love one another ‘in God.”‘ God much haunts his mind, as in the famous dictum, “An author in his book must be like God in the universe, present everywhere and visible nowhere.” God does not lecture, except to the Old Testament Israelites, who did not always listen. The modernist writer does not lecture; he creates, he dreams, he deciphers his hieroglyphs, he exists in a state of conscious antagonism to the busy bourgeois world. The lecture is an instrument of the bourgeoisie, a tool in the mass education essential to modern democracies. Where Flaubert says that no bond exists between the crowd and literary artists, the crowd offers to make one and invites the writer to lecture. “Descend from your ivory tower,” the crowd cries, “and come share, O bayadere, your fabulous perfumes with us.” Godlike and savage in his purest conception of himself, the author is thus brought back into society, into the global village, and trivialized into being an educator and a celebrity.

Lectures by authors go back, in the United States, to the so-called Lyceum Circuit, which, beginning in the 1830s, brought to the vastly scattered American provinces inspirational and educational speakers. Ralph Waldo Emerson was such a star, hitting the road with secular sermons culled from his journals, and then collecting these oral gems into the volumes of essays that are among the classic texts of American style and thought. Mark Twain, a generation and a half later, began as a comic lecturer, a stand-up comedian without a microphone, and his best-selling novels and travel accounts retained much of the crowd-pleasing platform manner.

Even writers one thinks of as relatively abstruse and shy at one point or other followed the lecture trail; Henry James toured the States coast to coast in 1904 and 1905 lecturing on “The Lesson of Balzac,” and Melville for a time in the late 1850s, when he was still somewhat famous as “the man who had lived among cannibals,” sought to generate the income that his books were increasingly failing to supply by speaking, at fifty dollars a lecture, on “Statues in Rome” and “The South Seas.” Even in its heyday the Lyceum style of bardic enterprise had its detractors among literary men: Hawthorne wrote in The Blithedale Romance of “that sober and pallid, or, rather, drab-colored, mode of winter-evening entertainment, the Lecture”; and Oliver Wendell Holmes returned from a tour reporting that “a lecturer was a literary strumpet.”

Advertisement

Yet as one tries to picture those gas-lit auditoriums of the last century, with the black-clad lecturer and his oaken lectern framed by velvet curtains heavy with gold tassels—curtains that the next night might part to reveal a scuffed and much-traveled opera set or the chairs of a minstrel show—one imagines an audience and a performer in sufficient agreement on what constituted entertainment and edification; the bonds between the culture-hungry and the culture-dispensing were stretched thin but not yet broken in the innocence of the New World wilderness. One thinks of the tremendous warmth Emerson established with his auditors, to whom he entrusted, without condescension or clowning, his most profound and intimate thoughts, and who in listening found themselves discovering, with him, what it was to be American. Even a figure as eccentric and suspect as Whitman traveled about, evidently, with a lecture on Lincoln.

Like book clubs and other movements of mass uplift, the lecture circuit gradually gravitated toward the lowbrow. The famous Chautauqua Movement, which persisted into the 1920s, blended with camp meetings and tent revival meetings—each a high-minded excuse to gather, with the usual mixed motives of human gatherings. The writers most admired in my youth did not, by and large, lecture, though some of the less admired and more personable did, such as the then ubiquitous John Mason Brown and Franklin P. Adams. But Hemingway and Faulkner and Fitzgerald and Steinbeck and Sinclair Lewis were rarely seen on stages; their advice to humanity was contained in their works, and their non-writing time seemed amply filled with marlin fishing, mule and bull fancying, and recreational drinking.

They were, by and large, a rather rough-hewn crew, adventurers and knock-abouts who had trained for creative writing by practicing journalism. Few were college graduates, though Fitzgerald’s years at Princeton were important to him and Lewis and Thornton Wilder had degrees from Yale. But doing was accepted as the main mode of learning. Hemingway began as a reporter for the Kansas City Star at the age of eighteen, and at the age of nineteen Eugene O’Neill quit Princeton and shipped out to sea. The world of print was wider then: a major American city might have as many as eight or ten daily newspapers, and a number of popular magazines paid well for short stories. The writers of this pre-television generation, with their potentially large bourgeois audience, yet were modernist enough to shy away from crowd-pleasing personal appearances; nor, in the matter of lecturing, is there much reason to suppose that they were often invited. Why would the citizens of Main Street want to hear what Sinclair Lewis thought of them? Gertrude Stein, of all people, went on a nationwide lecture tour in 1934, speaking in her complacently repetitive and cryptic style on such topics as “What is English Literature,” “The Gradual Making of the Making of Americans,” and “Portraits and Repetition.” One suspects, though, that the audiences came to hear her much as they had flocked to hear Oscar Wilde in 1882—more for the spectacle than the sense, and to be titillated by the apparition of the writer as an amusing exotic.

In the United States, the four decades since the end of World War II have seen the reduction of literary artists to the status of academic adjuncts. Where creation is taken as a precondition for exposition, the creator is expected to be, in Proust’s phrase, “prodigal of himself.” It is not merely that poets out of economic necessity teach in colleges and read their works in other colleges and in time understandably take as a standard of excellence a poem’s impact upon a basically adolescent audience; or that short-story writers move from college writing program to summer workshop and back again and consider actual publication a kind of supplementary academic credential, and a karmic turnover of writing students into graduate writing students into writing teachers takes place within an academic universe sustained by grants and tax money and isolated from the marketplace and popular awareness. It is not merely that contemporary novels are studied for course credit and thus given the onus of the compulsory and, as it were, the textbook-directed—a modernization of the literary curriculum, one might remark, that displaces the classics and gives the present a kind of instant dustiness. It is that American society, generously trying to find a place for this functionary, inherited from other epochs, called a writer, can only think to place him as a teacher and, in a lesser way, as a celebrity.

He is invited to come onto television and have his say, as if his book, his poor thick unread book, were not his say. He is invited to come into the classroom and, the meagerest kind of expert, teach himself. Last century’s Lyceum Circuit has moved indoors, from the open air of a hopeful rural democracy to the cloistered auditoriums of the country’s fifteen hundred accredited colleges and universities; the circuit has been, as it were, miniaturized. Though the market for actual short stories is down, in the vastness of the United States, to a half-dozen or so paying magazines, the market for fiction writers, as adornment to banquets and conferences and corporate self-celebrations, is booming. Kurt Vonnegut has observed that an American writer gets paid more for delivering a speech at a third-rate bankrupt college than he does for writing a short-story masterpiece. Even I, a relatively obscure and marginally best-selling writer, receive almost every day an invitation to speak, to “read,” to lecture.

I do not wish to complain or to exaggerate. Sociological situations have causes that are not altered by satire or nostalgia. The university and the print shop, literature and scholarship have been ever close, and the erratic ways in which writers support themselves and their books seek readers have changed a number of times since the Renaissance days when poets sought with fulsome dedications to win the support of noble patrons. The academicization of writing in America is but an aspect, after all, of the academicization of America. The typical writer of my generation is college-educated; in fact I am rather a maverick in having avoided graduate school and not possessing an advanced degree. Academically equipped and habituated, John Barth and Joyce Carol Oates, for instance, naturally are drawn to teach and to lecture. They know a lot, and the prestige of their authorship adds a magic shimmer, a raffish spin, to their knowledge. Writers such as they stand ready to participate in the discourse of civilized men and women, just as, in prewar Europe, writers like Mann and Valéry and Eliot could creditably perform in the company of scholarly gentlemen.

Until the arising, not so many centuries ago, of a large bourgeois audience for printed material and with it the possibility of professional writers supported by the sales of their works, writers had to be gentlemen or daughters of clergymen or courtiers of a kind; like jesters, writers peeked from behind the elbow of power, and if, in a democracy without a nobility or much of a landed gentry, the well-endowed universities, as the bourgeois audience ebbs, step in and act the part of patron, where is the blame? Who longs for the absinthe-soaked bohemia that offered along with its freedom and excitement derangement and despair, or for the barren cultural landscape that so grudgingly fed the classic American artists? Is not even the greatest American writing, from Hawthorne and Dickinson to Hemingway and Faulkner, and not excluding Whitman and Twain, maimed by the oddity of the native artist’s position and the limits of self-education? Perhaps so; but we suspect in each of the cases named that the oddity is inextricable from the intensity and veracity, and that when the writer becomes a lecturer, a certain intensity is lost.

Why should this be so? To prepare and give a lecture, and to observe the attendant courtesies, takes time; but time is given abundantly to the writer, especially in this day of antibiotics and health consciousness, more time than he or she needs to be struck by his or her particular lightning. There was time enough, in the life of Wallace Stevens, to put in eighthour days at his insurance company in Hartford; time enough, in the life of Rimbaud, to quit poetry at the age of nineteen; time enough, in the life of Tolstoy, to spurn art entirely and try to educate the peasants and reinvent religion. We feel, in fact, that if a writer’s life does not have in it time to waste—time for a binge or a walk in the woods or a hectic affair or a year of silence—he can’t be much of a writer. While paint and music possess something like an absolute existence, language is nonsense without its referents, which exist in nature. A writer serves as an interface between language and nature. In a sense none of his time is wasted, except that in which he turns his back on nature, shuts down his osmotic function, and tries to lecture.

Asking a writer to lecture is like asking a knife to turn a screw. Screws are necessary to hold the world together, the tighter the better, and a screwdriver is an admirable tool, more rugged and versatile and less dangerous than a knife; but a knife with a broken tip and dulled or twisted edge serves all purposes poorly. Of course, if a knife is repeatedly used as a screwdriver, it will get worn into the shape of one; but then don’t expect it to slice any more apples.

Perhaps, in this electronic age, one should attempt to speak of input and output and static. Invited to lecture, the writer is flattered. He feels invited up, after years of playing on the floor with paper dolls and pretend castles, into grown-up activity, for which one wears a suit, and receives money or at least an airplane ticket. He furthermore receives society’s permission, by the terms of the contract, to immobilize an audience of some hundreds or at least dozens of fellow human beings. I must be, he can only conclude, an interesting and worthy person. With this thought, on this particular frequency, static enters the wave bands where formerly he was only hearing the rustle of paper dolls—static, alas, that may be slow to clear up. Input and output are hard to manage simultaneously. A writer on show tends not to see or hear much beyond his own performance. A writer whose thinking has become thoroughly judgmental, frontal, and reasonable is apt to find his creative processes clogged.

A work of fiction is not a statement about the world; it is an attempt to create, out of hieroglyphs imprinted by the world upon the ego of the writer, another world. The kind of precision demanded concerns how something would be said, how someone or something would look, or how closely the rhythm of a paragraph suggests the atmosphere of a moment. The activity feels holy, and is attempted with much nervousness and inner and outer circling, and consummated with a sense of triumph out of all apparent proportion to the trivial or even tawdry reality that has been verbally approximated. Compared to such precision, everything that can be said in a lecture feels only somewhat true, and significantly corrupt. All assertions feel rash, and all generalizations arguable. Lecturing deprives the author of his sacred right to silence, of speaking only on the firm ground of the imaginary. For the mind whose linguistic habits have been shaped by the work of embodiment, assertions, however subtly and justly turned, are a self-violation; and if the violation is public, as a lecture is, the occasion partakes of disgrace—of confession that one has deserted one’s post, has forsaken one’s task for a lesser, however richly society has wrapped the occasion in plausibility and approval.

But how understandable it is, after all, for society to assume that the writer has something to say. To assume the opposite—that the writer has nothing to say—seems scandalous, though it is somewhat true, at least to the degree that we all have nothing to say, relative to the immense amount of saying that gets done. Most human utterance is not communication but a noise, a noise that says, “I am here”—a noise that says, “You are not alone.” The value, for the author, of a lecture is that he confesses, by giving one, that he too needs to make this noise, that he is a member of society, that he is human. The Flaubertian pose of God the creator (“paring his fingernails,” James Joyce added in a famous specification—“within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails”) yields in these postmodern times to the pose of a talkative good fellow, a fellow speaker, contributing his bit to the chatter that staves off the silence that surrounds us as we huddle around the tribal fire.

Giving a lecture gets the writer out into the world, and in its moment of delivery enables him to taste the ancient bardic role. It confronts him with an audience, and healthily deprives him of the illusion that he is his own audience, that his making, like the Lord’s, takes place in a void. In the literary art, however abstruse or imagist, surreal or impersonal, communication is hoped for, and communication implies the attempt to alter other minds. This is the shameful secret, the tyrannical impulse, hidden behind the modernist pose of self-satisfying creation. A Western writer who has traveled even a little in the third world has encountered the solemn, aggressive question, “What is the writer’s social purpose? How do you serve your fellow men?” It seems embarrassing and inadequate to reply honestly that—if one is a fiction writer—one serves them by constructing fantastic versions of one’s own life, spinoffs from the personal into the just barely possible, into the amusingly elaborate. Giving a lecture reminds the writer of another dimension of his task, that of making contact—“our terrible need to make contact,” in Katherine Mansfield’s great phrase. A writer needs to make contact with his nation; his work in a sense is one long lecture to his fellow countrymen, asking them to face up to his version of what his life and their lives are like—asking them, even, to do something about it.

The very book, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, that contains the description of the godlike artist paring his fingernails ends with this altruistic vow of the hero, Stephen Dedalus, Stephen the artificer: “Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” The authorial interface, by this formulation, is between the reality of experience and the race, whose conscience and consciousness must be, repeatedly, created. Certainly Joyce’s emotional and aesthetic loyalty to an Ireland where he couldn’t bear to live is clear enough, as is his attempt, in the two long and unique novels that succeeded Portrait of the Artist, to re-create the bardic persona—to sing, that is, in epic form, the entire history of his city and nation. And Proust, too, amid the magnificent unscrolling of his own snobbish and hyperesthetic life, sings hymns to French cathedrals, French place names, and the visions of French history. Kafka, doubly alien, as a German-speaking Jew within a Czech-speaking province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and a writer furthermore for whom publication was a kind of desecration, yet has the epic touch; his parables of rootlessness are securely rooted in the landscape and civic machinery of Bohemia and Prague, where, amid the dreariness and caution of the present Communist regime, he is revered as a national prophet.

One could go on with this catalog of tribal resonances, for a mark of a great writer, as Walt Whitman observed, is that a nation absorbs him, or her, in its self-knowledge and self-image. The confident writer assumes that his own sensibility is a sufficient index of general conditions, and that the question “Who am I?” if bravely enough explored, inevitably illuminates the question “Who are we?”

But if giving a lecture calls the writer down from his ivory tower and administers a healthy dose of humanity, what benefit does the audience receive? Why invite this person to give a type of performance he is instinctively reluctant to give, and does not give very well? Thomas Mann, in preparing the way for his own lecture of Freud, gracefully suggested that the author is especially called to celebrations, for “he has understanding of the feasts of life, understanding even of life as a feast.” I would suggest, furthermore, that feasts traditionally require, within their apparatus, a figure of admonition, a licensed representative, sometimes costumed as a skeleton and wearing a grinning skull-mask, of those dark forces that must be acknowledged before the feast can be wholly enjoyed. It used to be that in America, at even the gayest of celebrations—at weddings, say, or at the opening of a new automobile agency—a clergyman, dressed in chastening black, would stand and, with his few words and declared presence, like a lightning rod carry off all the guilt and foreboding that might otherwise cloud the occasion, and thus release the celebrants to joy.

As the Church’s power to generate and discharge guilt fades; the writer, I suggest—the representative of the dark and inky world of print—has replaced the priest as an admonitory figure. In this electronic age, when everyone is watching television and even book critics (as Leslie Fiedler has confided) would rather go to the movies, books make us feel guilty—so many classics gathering dust unread, so many new books piling up in bright heaps, and above this choking wasteland of print the plaintive cries of sociologists waving fistfuls of tabulated high-school tests and shrieking to us how totally illiterate we are all becoming. Gutenberg is dead, but his ghost moves among us as a reproachful specter. What better exorcism, that the feast of life may tumble on untroubled, than to invite a writer to lecture?

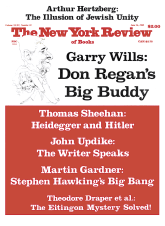

This Issue

June 16, 1988