Seventeen years ago I attacked the World Psychiatric Association in these pages in “Betrayal by Psychiatry”1 for refusing to hear complaints from Soviet dissidents, including Andrei Sakharov, about the political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union. The WPA staged a repeat performance a few weeks ago at a regional meeting here in Washington.

The WPA leadership turned down a request from Western and Soviet activists to present a symposium on “Soviet Psychiatry in the Gorbachev Era.” The centerpiece of that symposium was to have been the poignant videotaped message by Alexander Podrabinek that was smuggled out of Moscow and published in the December 8 issue of The New York Review. The WPA leadership is anxious to get the official Soviet psychiatric organization back into the WPA. It is apparently willing to do so without first eliciting firm assurances from the Soviet authorities that past abuses will not recur.

A symposium on “Soviet Psychiatry in the Gorbachev Era” could have provided an opportunity to invite the Soviets to hear an independent assessment of recent changes, to clear the air of fresh complaints, to present their side of the story, and open the way for their readmission. That would be glasnost in action. But official Soviet psychiatrists and their Western allies are in no mood for such a cleansing dialectic. The Soviets want readmission on their own terms, without conditions.

As a result the delegates to the regional conference did not get a chance to hear for themselves what experts on Soviet psychiatry had to say. They were able to present their views only in an unofficial meeting arranged by the International Association on the Political Use of Psychiatry on a late Friday afternoon. Only a minority of the conference participants were present, and except for full coverage by West German television, it attracted meager attention in the press. The only story I saw about the symposium was in The New York Times (Sunday, October 16), which failed to report that the WPA leadership had refused to permit the discussion to be held at the regional meeting, when all the delegates could more easily have heard it.

Other participants in the symposium included Peter Reddaway of the Kennan Institute, Dr. Sidney Levine from the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Great Britain, Robert van Voren from the International Association on the Political Abuse of Psychiatry with headquarters in Holland, Paul Chodoff of the American Psychiatric Association, and Dr. Anatoly Koryagin, the Soviet psychiatrist who dared to expose Soviet abuses and was first jailed and then expelled from the USSR. All expressed misgivings about the reluctant pace of Soviet reform and the refusal of the Soviet authorities to admit that the political abuse of psychiatry against political dissenters had ever occurred, let alone to condemn the practice. Their criticism was reinforced by Dr. Sakharov’s complaint on his recent visit to the US that dissidents were still being held in psychiatric hospitals.

In addition to the WPA’s foray into protective censorship, its leaders, including a key committee chairman from East Germany, have set in motion a plan to amend its voting procedures to make it easier for the Soviets to reenter the WPA without facing a fresh debate on past—and present—abuses.

The excuse for its rejection of the symposium given by the WPA to the American Psychiatric Association, which was the host for the regional meeting and was anxious for the symposium to be heard, was that “the symposium has a content that is well known to everybody. The content is hardly scientific and it will not serve to promote international collaboration.” But Michael Gordon of The New York Times drew a more succinct and candid explanation from Dr. Costas Stefanis, the Greek professor of psychiatry who is president of the WPA. Dr. Stefanis said his organization “must be careful not to interfere in the Soviet Union’s internal affairs.” This standard would nullify the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Helsinki accords. It is the same reply South Africa gives to critics of apartheid.

Dr. Stefanis said the Soviet psychiatric association had expressed its “willingness to apply” for readmission in the WPA. But he did not say whether this willingness was subject to the same conditions laid down by Alexander Churkin, chief psychiatrist of the Soviet Ministry of Health, at a press conference in Moscow last February. “We are ready to come back,” Dr. Churkin said, “provided the executive board and the association will be a working atmosphere and political activity will not be discussed there” (The Washington Post, February 12, 1988).

In other words the Soviets want guarantees of protection from further criticism. The West, not Moscow, must “reform.” This is glasnost glazed over. The political abuse of psychiatry is to be declared out of bounds because it is political! The Hippocratic oath made the physician swear that “the regimen I adopt will be for the benefit of my patients…and not for their hurt or any wrong.” Neither Greek tyrants nor Roman emperors ever ventured to suggest amending it to read, “unless so ordered by political authority.” Indeed at one point in current negotiations between Moscow and the State Department for an exchange of “visits of inspection” between US and Soviet psychiatrists, Moscow refused to accept any official delegation from the American Psychiatric Association unless it first apologized for its past criticism of Soviet psychiatric abuses.

Advertisement

World opinion should be on guard against current Soviet reassurances. One of the reforms promised is the transfer of the notorious “special psychiatric hospitals”—like the dreaded Serbsky Institute—from the Ministry of the Interior to the Ministry of Health. But Dr. Churkin’s statements at last February’s press conference did not create much confidence in this shift of jurisdiction. Dr. Churkin said that the Soviet Union withdrew from the WPA in 1983 because it had become too politicized. The whole truth, as he must know, is that in 1983 the Soviets sent to the World Psychiatric Association headquarters, then in Vienna, delegates who were prepared to discuss some specific cases. But they had hardly arrived when they were suddenly called home and the Soviets withdrew from the WPA rather than face a debate on reform.

Current doubts are reinforced by the recent “multicandidate” election for the head of the All Union Society of Psychiatrists, the main Soviet psychiatric organization. According to the recent reforms, multicandidate elections are supposed to democratize one-party rule. But the three candidates—in a carefully orchestrated system of indirect voting—were Drs. Georgi Morozov, Marat Vartanyan, and Nikolai Zharikov, all of whom were long associated with the late Dr. Andrei V. Snezhnevsky, who made Soviet psychiatry a complaisant tool of the KGB. More recently, under glasnost, the Soviet press had itself begun to open up on Soviet psychiatric abuses. But it has never directly discussed the forbidden topics of psychiatric mistreatment of dissidents. The nearest thing to such an admission occurred at the same February press conference. Dr. Modest Kabanov, a psychiatrist from Leningrad, which has generally been more liberal than Moscow in psychiatric matters, then acknowledged that in the past some doctors had sent people to mental institutions for reading authors frowned upon by the political authorities. He cited two such writers—Bulgakov and Pasternak.

Dr. Kabanov said, “Of course such mistakes will not be repeated.” But nothing was said about legal reforms that might prevent such travesties of psychiatry from being repeated.

The abuse of psychiatry seems to be a major grievance in the flood of complaining letters to the editor evoked by the promise of glasnost. Even a cursory sampling of the “Current Digest of the Soviet Press” and the US Foreign Broadcast Information Service will show how many Soviet publications have reported complaints of such abuses. Some papers have been scornful of the official explanations these have elicited.

In one case these letters led to a splendid piece of investigative reporting in Komsomolskaya Pravda, organ of the Komsomol, the Communist Youth League, on November 11 of last year. It was a 4,500-word blockbuster by a team of two staff correspondents and a psychiatrist. The headlines indicate its sweep: “Under Broad Definition of Schizophrenia Many ‘Troublesome’ People Are Forcibly Hospitalized; Psychiatrists (Some of Whom Take Bribes for Diagnoses) Fight Inquiries; Facilities in Poor Condition.”

An editor’s note said, “For many years now psychiatric science and practice have been walled off from openness by a high and impenetrable fence. But behind the fence lawlessness is taking place.”

Nothing was said in the article, however, about the psychiatric confinement of political dissidents. The heroine of the exposé was not a dissident at all but a good Communist Party member, indeed too good for her own safety. She was turned over to a psychiatrist by the management of her factory because she was what we call a “whistle-blower,” too conscientious and outspoken for her superiors. Her examination by the psychiatrist reads like something made to order for a modern-day Gogol. The doctor suspected that she was sexually deprived. He asked her why she didn’t get married. “At your age,” he advised her, “people normally think about love, not justice. Where do you hurt?”

To which, according to Komsomolskaya Pravda, she replied, “My soul hurts. There are so many disgraceful things all around.”

“Your soul must get some medical treatment,” the psychiatrist decided. He telephoned for two orderlies who took her off to a psychiatric hospital.

In her case, “soul” and a passion for justice were diagnosed as morbid symptoms requiring hospitalization.

It would be interesting to know from the journalists at Komsomolskaya Pravda just what happened after their exposé. Was this young Communist restored to her factory job, or is she still somewhere in limbo though presumably out of the hospital? Were the factory managers—and their dutiful psychiatrist—punished for what they did? Was morale among workers in that factory improved by the spectacle of the bosses being brought to justice? Or was Komsomolskaya Pravda, perhaps, reproved for too much glasnost?

Advertisement

The heroine of this exposé sounds like the industrial counterpart of the good Communist, too good for her own welfare, that Solzhenitsyn portrayed in his tender short story, “Matryona’s House,” which Sartre published many years ago in Temps Modernes. The moral of both stories is that many years after the Revolution, it is dangerous to try to be a good Communist in the Soviet Union.2

This, and not cosmetic changes to placate Western opinion and facilitate Western credits, is the basic problem for Gorbachev and his reforms. How do you end stagnation and inspire people to work for the common good without reviving their spirit? How can you revive their spirit without getting rid of the laws and the practices that protect dishonest managers and party bosses in the factory and on the farm, from workers brave enough to blow the whistle on them? It is hard enough to do this right here in Washington. It is immeasurably harder in the Soviet Union where the risks are more frightful.

The soul of the Soviet, and especially the Russian, people has been broken by years of government by terror. The peasants remember what happened to the good farmers who were liquidated as kulaks. Potential entrepreneurs fear that they may once again be swept away as were the Nepmen after they served Lenin’s immediate needs following the horrors of War Communism. Within the Party—that secular Church with a capital “P”—everyone has seen how lickspittles prosper and idealists are treated as insane. It’s no surprise that the old Marxist chestnut has been turned upside down and vodka has become the religion of the people, their one sure respite from harebrained and corrupt rulers.

Misgivings about Soviet psychiatry were given fresh weight recently by the interview that Viktor Chebrikov, then head of the KGB, now chairman of the new Central Committee Commission on Legal Affairs, gave Pravda. This interview, in which Chebrikov lauded the “lofty humanist ideals” of the KGB, hardly reflected the change of mentality required for genuine reform. What the West and Soviet dissidents have called psychiatric abuses Chebrikov described as the benign practice of preventative political medicine by the KGB. This interview has not been given the attention it deserves though it covered the first two full pages of Pravda on September 2. It was headed “Perestroika and the Work of the Chekists.” Cheka was the name of the secret police in the days of Lenin.

Pravda began the interview by saying that it had been receiving a lot of mail from readers about the secret police. But unlike Komsomolskaya Pravda, the Pravda article did not speak of complaints or abuses, or inquire how, under perestroika, “mistakes” could be prevented in the future. It set a respectful and even obsequious tone. “There are many letters in the editorial mail,” Pravda began, “asking for information about the activity of the USSR KGB under the conditions of perestroika.” It added circumspectly that “there are also other questions about the work of the Chekists.”

These “other questions” were not specified. But many are raised by the broad scope of the KGB’s mandate as set forth by Chebrikov. He said that the KGB had a dual “security” function. One part was “promptly exposing and stopping intelligence and subversive activity by foreign special services.” The other was to deal with “hostile actions by persons of an anti-Soviet, antisocialist disposition within the country that are aimed at undermining and eliminating our existing system.” This is broad and vague enough for a Stalinist style witch hunt.

The question unanswered in the lengthy interview was how these objectives were to be reconciled with glasnost and perestroika. Where is the line to be drawn between the promised democratization and forbidden attempts to change “the system”? Chebrikov’s standards are loose enough to put Gorbachev himself in the clink should there be a shift of forces in the Politburo. Recently a demonstration in Moscow for multiparty free elections was swiftly smashed by the police. Two new laws restrict demonstrations and widen the powers of the police to enter private homes without a warrant in search of subversives.

When Pravda asked Chebrikov about “ideological sabotage,” he went into what can only be described as a paranoid tirade, as overwrought as J. Edgar Hoover’s warnings in our haunted Fifties about the red menace in America. Chebrikov said foreign “special services” were

resorting to the most cunning devices in order to exacerbate the internal political situation in the USSR. They are attempting to discredit the leading role of the Communist party and to inspire the emergence of a political opposition on the basis of some autonomous groupings…. Foreign subversive centers persistently try to introduce into Soviet people’s consciousness the idea that the negative phenomena in our country’s economic and social life supposedly stem from the very essence of the socialist system…. They strenuously proclaim the values of bourgeois democracy. Unfortunately people are to be found who—if it is possible to express it so—take the bait.

Against this insidious hydra-headed conspiracy, Chebrikov stressed the “preventive work” of the KGB in “helping the deviant to shed his delusions and comprehend the relationship between the interests of the individual and society.” Here Chebrikov sees a great role for the KGB providing it does not forget “the lofty humanist nature” of its work.

It is a pity that Chebrikov was not asked what role he envisaged for Soviet psychiatry in curing deviants of their delusions. Chebrikov seems himself in need of restructuring. And perhaps just a little psychiatric therapy.

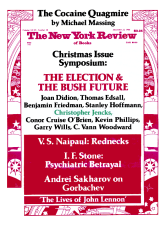

This Issue

December 22, 1988

-

1

The New York Review, February 10, 1972.

↩ -

2

Novy Mir, which published Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich in the Khrushchev era, and was forbidden under Brezhnev to publish his First Circle and his Cancer Ward, was about to announce last month that under Gorbachev it had been granted permission to begin the publication of Solzhenitsyn’s works in 1989. But according to a dispatch by David Remnick in the Style section of The Washington Post of October 22, 1988, the issue containing this historic announcement had to be yanked off the press after the first copies had already been printed and even reached some subscribers in the Ukraine. The announcement was then taken off the cover and the million-copy press-run started all over again. Who in the Politburo had the clout to countermand the original permission to print is not known, but Chebrikov is certainly a prime suspect. The KGB must be desperate to keep Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago from publication in the USSR.

↩