Fifty-two years ago, on June 27, 1936, I reviewed a book in The Nation. Very favorably. The author, Felipe Alfau, was said to be a young Spaniard writing in English. Spain was Republican then; the Franco revolt that turned into the Spanish Civil War began on July 19, three weeks and a day later. The charm exercised on me by Locos, therefore, cannot have been a matter of politics. And I was ignorant of Spain and Spanish. It was more like love. I was enamored of that book and never forgot it, though my memory of it, I now perceive on rereading, is somewhat distorted, as of an excited young love affair. Alfau, or his book, was evidently my fatal type, which I would meet again in Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire and more than once in Italo Calvino. But Locos was the first. And it appears to have been the author’s unique book, fittingly, as it were. I never heard of Alfau again, though for a time I used to ask about him whenever I met a Spaniard; not one knew his name. Maybe that was because he lived in the United States, if indeed he did.1 But in this country I never found anyone besides me who had read Locos. Now the book is being reissued.2 Launched more than fifty years ago by a Farrar and Rinehart club of so-called “Discoverers,” it has been rediscovered, by what means I don’t know.

To come back to it has been a bit eerie, at least on first sight—a cross between recognition and non-recognition. For example, what has stuck in my memory is a lengthy account of a police convention in Madrid that coincided merrily with a crime wave, the one giving rise to the other: crooks converged on the city, free to practice their trade while the police attended panel discussions and lectures on criminality. Well, it would be too much to say that none of that is in Locos; it is there but in the space of a few sentences and as a mere suggestion.

The fifth chapter, “The Wallet,” begins: “During the 19— police convention at Madrid, a very unfortunate occurrence took place. Something went wrong with the lighting system of the city and the whole metropolis was left in complete darkness.” It is the power failure that offers the assembled criminals their opportunity.

It was a most deplorable thing, for it coincided with the undesirable immigration of a regular herd of international crooks who since the beginning of the World War had migrated into Spain and now cooperated with resident crooks in a most energetic manner…. As if all these people had been waiting for that rare opportunity, the moment the lights went out in Madrid, thieves, gunmen, holdup men, pickpockets, in short all the members of the outlaw family, sprang up in every corner as though by enchantment.

Then:

It came to pass that during the Police Convention of 19—, Madrid had a criminal convention as well. Of course, the police were bestowing all their efforts and time upon discussing matters of regulation, discipline and now and then how to improve the method of hunting criminals…and naturally, after each session…had neither time nor energy to put a check to the outrages…. Therefore all crooks felt safer and freer to perform their duty in Madrid, where the cream of the police were gathered, than anywhere else.

That is all, a preamble. The body of the chapter has to do with the stolen wallet of the Prefect of Police. The power failure, which provides a realistic explanation, had slipped my memory, and I was left with the delightful illogic—or logic—of parallel conventions of police and criminals. The purest Alfau, a distillate.

“The Wallet,” actually, may be the center of the book, whose subject is Spain regarded as an absurdity, a compound of beggars, pimps, policemen, nuns, thieves, priests, murderers, confidence artists. The title, meaning “The Crazies,” refers to a Café de los Locos in Toledo, where in the first chapter virtually all the principal characters are introduced as habitués suited to be “characters” for the fiction writers who, like the author, drop in to observe them. There are Dr. de los Rios, the medical attendant of most of the human wreckage washed up at those tables, Gaston Bejarano, a pimp known as El Cogote, Don Laureano Baez, a well-to-do professional beggar, his maid/daughter Lunarito, Sister Carmela, who is the same as Carmen, a runaway nun, Garcia, a poet who becomes a fingerprint expert, Padre Inocencio, a Salesian monk, Don Benito, the Prefect of Police, Felipe Alfau, Don Gil Bejarano, a junk dealer, uncle of El Cogote, Pepe Bejarano, a good-looking young man, brother of El Cogote, Dona Micaela Valverde, a triple widow and necrophile.

Advertisement

Only missing is the highly significant Señor Olózaga, at one time known as the Black Mandarin, a giant, former galley slave, baptized and brought up by Spanish monks in China, former butterfly-charmer in a circus, former potentate in the Spanish Philippines, now running a bizarre agency for the collection of delinquent debts and another for buying and selling dead people’s clothes. But he is connected with the other “characters” of the Café de los Locos both in his own right and by marriage to Tía Mariquital, his fifth wife, who lives in a house that coughs—their secretary, mistaken for her husband, is murdered by Don Laureano Baez and his daughter/maid Lunarito, one of many cases of mistaken identity. As the Black Mandarin, moreover, in the Philippines, he has sought the hand of the blue-eyed daughter of Don Esteban Bejarano y Ulloa, a Spanish official, and been rejected because of his color. This, precisely, was the father of Don Gil Bejarano (see above), the brother-in-law of the Prefect of Police and inventor of a theory of fingerprints, which pops up in Chapter 4, where, incidentally, we find Padre Inocencio playing cards with the Bejarano family while the young daughter, Carmen, is having sex with her brother Gaston.

Such underground—or underworld—links are characteristic and combine with the rather giddy mutability displayed by the characters. Lunarito is Carmen, who is going to be Sister Carmela; at one point we find her married to El Cogote, none other than her brother Gaston, who cannot, of course, be her brother if she is the daughter of the beggar, Don Laureano Baez. And yet Don Laureano’s wife, when we are introduced to him as the bartender of the Café de los Locos, is Felisa, which is the name of Carmen’s mother, the sister of Don Benito, the Prefect of Police…. In the Prologue, and occasionally thereafter, the author makes a great point of the uncontrollability of his characters, but this familiar notion (as in “Falstaff got away from Shakespeare”) is the least interesting feature. The changing and interchanging of the people, resembling “shot” silk, has no need of the whimsy of a loss of auctorial control. If any aspect of the book has aged, it is this whimsicality.

It is not only the characters of Locos that have that queer shimmer or iridescence. Place and time are subject to it as well. A fact I think I missed back in 1936 is the discrepancy between the location of the Café de los Locos—Toledo—where the “characters” are gathered for inspection, and their actual residence—Madrid. What are these Madrilenos doing in Toledo? I suppose it must be because of the reputation of Toledo as a mad, fantastic city, a myth, a city, as Alfau says, that “died in the Renaissance”; he speaks of “Toledo on its hill…like a petrified forest of centuries.” The city that died in the Renaissance and lives on, petrified, can of course figure as an image of Spain. One more quotation may be relevant to the underlying theme of impersonation as a national trait: “The action of this book develops mainly in Spain, a land in which not the thought nor the word, but the action with a meaning—the gesture—has grown into a national specialty.”

Spain and its former possessions—Cuba and the Philippines—constitute the scene; their obverse is China, for a Spaniard the other end of the world, and here the provenance of Señor Olózaga, baptized “Juan Chinelato” by the bearded, tobacco-smoking monks who raised him.

One thing that certainly escaped me as a young reviewer is the hidden presence of this “Juan Chinelato” in the first chapter, the one called “Identity” and laid in the Café of the Crazies. He is there in the form of a little Chinese figure made of porcelain being hawked by Don Gil Bejarano in his character of junk dealer. “Don Gil approached us,” writes Alfau.

“Here is a real bargain,” he said, tossing the porcelain figure on the palm of his hand. “It is a real old work of art made in China. What do you say?” I looked at the figure which was delicately made. It represented a herculean warrior with drooping mustache and a ferocious expression. He had a butterfly on his shoulder. The color of the face was not yellow but a darker color, more like bronze…. “Perhaps it is not Chinese but Indian.” Don Gil…looked slightly annoyed. “No, it is Chinese,” he said.

And he continues to praise it: “Yes, this is a real Chinese mandarin or warrior, I don’t know which, and it is a real bargain.” A minute later, thanks to an inadvertent movement, the figure is smashed to pieces on the marble-topped café table.

Advertisement

This is a beautifully constructed book and full of surprises. Another example: one does not notice in this opening chapter the unusually small hand of Don Gil, seen only as a mark on a whitewashed wall. The lightly dropped hint is picked up unobtrusively like a palmed coin several chapters later when Don Gil is being arrested at the reluctant order of his brother-in-law because his fingerprints have been found all over the scene of a crime: “Don Gil had very small hands…and the handcuffs did not fit securely enough…. ‘Officer, those handcuffs are too big for me. You had better get a rope or something.’ ” In his conversations with the Prefect, he has kept invoking “the man from China,” that is, the man who has the perfect alibi but is tracked down by science through the prints his hands have left. Don Gil’s last article, published in a Madrid newspaper on the day of his apprehension, is entitled “Fingerprints, a sure antidote against all alibis,” and his last words, which he keeps reiterating as he is carried off in the police wagon, are “I am the man from China…. Fingerprints never fail.”

Perhaps police work and criminality, just as much as mad, fantastic Spain, are the subject of Locos. And considerable detection is required on the reader’s part, to be repaid, however, as in the case of “Wanted” lawbreakers, with a handsome reward. For instance, among the clues planted to the mute presence of Señor Olózaga in the Café of the Crazies there is simply the word “butterfly”; I failed to catch the signal until the third reading. And I still have a lot of sleuthing to do on Carmen-Carmela-Lunarito and the beauty spot on Lunarito’s body that she charges a fee to show. A knowledge of Spanish might help. In the Spanish light, each figure is dogged by a shadow, like a spy or tailing detective, though sometimes the long shadow is ahead: “She stood at the end of her own shadow against the far diffused light of the corner lamppost and there was something ominous in that.” It may be that this is the link between the theme of Spain and the theme of the criminal with his attendant policeman. In some moods Locos could be classed as “luminist” fiction. But I must leave some work (which translates into pleasure) for the reader.

If Locos is, or was, my fatal type, what I fell in love with, all unknowing, was the modernist novel as detective story. There is detective work, surely, supplied by Nabokov for the reader of Pale Fire. I mentioned Calvino, too, but there is another, quite recent example, which I nearly overlooked. The Name of the Rose, of course. It is not only a detective story in itself but it also contains an allusion to Sherlock Holmes and the Hound of the Baskervilles. But in Locos Sherlock Holmes is already present: while in England Pepe Bejarano pretends to have studied under him, which explains his uncanny ability to recover his uncle, the Prefect’s, wallet. The grateful police officer, who does not know whether Conan Doyle’s creation is a real person or not, wants to express his thanks. “Yes, Pepe, yes, I should like to write an official letter to that gentleman, to that great man—Cherlomsky, is that the name?”

Yes, there is a family resemblance to Nabokov, to Calvino, to Eco. And perhaps, though I cannot vouch for it, to Borges, too.

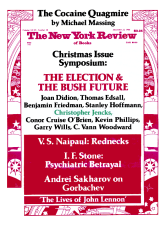

This Issue

December 22, 1988