Traveling in the South, I had the vaguest idea of what a redneck was. Someone intolerant and uneducated—that was what the word suggested. And it fitted in with what I had been told in New York: that some motoring organizations gave their members maps of safe routes through the South, to steer them away from areas infested with rednecks. Then I also became aware that the word had been turned by some middle-class people into a romantic word; and that in this extension it stood for the unintellectual, physical, virile man, someone who (for instance) wouldn’t mind saying “shit” in company.

It wasn’t until I met Campbell in Jackson, Mississippi, that I was given a full and beautiful and lyrical account, an account that ran it all together, by a man who half looked down on, and half loved, the redneck, and who, when he began to speak of redneck pleasures, was moved to confess that he was half a redneck himself.

It wasn’t for his redneck side, strictly speaking, that I had been introduced to Campbell. I had been told that he was the new kind of young conservative, with strong views on race and welfare. It was of family and values and authority that we spoke, all quite predictably, until it occurred to me to ask: “Campbell, what do you understand by the word ‘redneck’?”

And—as though it had been prepared—a great Theophrastan “character,” something almost in the style of the seventeenth-century character-writers, poured out of Campbell. It might have been an updated version of something from Elizabethan lowlife writing or John Earle’s Microcosmography, or something from Sir Thomas Overbury. (Sir Thomas Overbury, on the English country gentleman, 1616: “His travel is seldom farther than the next market town, and his inquistion is about the price of corn. When he travelleth, he will go 10 mile out of the way to a cousin’s house of his to save charges; and rewards the servants by taking them by the hand when he departs.”)

Campbell said: “A redneck is a lower blue-collar construction worker who definitely doesn’t like blacks. He likes to drink beer. He’s going to wear cowboy boots.”

That was the concrete, lyrical way Campbell spoke. But it would be better at this point to go back and hear a little of what he said about himself.

“My father was born in Alabama, and his family picked themselves up, left the farm they owned, 360 acres, left it and came to Mississippi to get an education. His father, my father’s father, and his mother said, ‘We got to get you guys over there to get you a good education.’ They obviously had some money saved to do that, pick up and leave. They kept the farm. Daddy sold it all five or six years ago. And when they came to Mississippi all the brothers got jobs when they weren’t in school. My father left Alabama in 1923-24. Graduated in 1928. Wound up having a garage and gas station. But they were happy. I never heard my father say a curse word in his life, and that’s the truth. He worked all the damn time. We weren’t ever real close. He didn’t have time to be close.

“My mother was a schoolteacher. I grew up in the Baptist church. I was pretty force-fed. We went to church as soon as the doors opened. We went there on Wednesdays for the prayer meeting. We would go for the big summer revivals. Go every night, bored to death.”

Then, without a pause, Campbell said: “In the long run it was the best thing I’ve ever had. My mom and dad gave me values that came back to me when I was twenty years old. But I’d rebelled out. Most of the children conformed. I really wanted to act crazy. I drank more, ran around more. I started working in a grocery store when I was twelve, and that’s the damned truth. I loved it. You met all the characters. You got all the black trade. They sat on the feed bags; mama came to town with four or five kids, and she had to nurse a couple. I liked working there. Always somebody coming in there. Hee-hawing all the time. You knew everybody who came in. It was a good store. This was Saturdays. I like the money. When I started I made four dollars a day. When I left I was making about seven.

“I cut right away. I drove a damn dumper truck in the summertime. They were constructing this interstate and they needed somebody who could read and write, to count the sacks of fertilizer that went into the airplane. They were fertilizing the sides of the road to get the grass to grow. It was boring as hell. These are days long gone. It’s funny how you change and mature. I wanted to be crazy. I had a good time being crazy.”

Advertisement

“You wanted to be one of the boys?”

“It’s important in northeast Jackson, as we call it, to be well liked, to be well thought of. But I wasn’t relating to the church. I’d go with my mama at Christmas time, but I was bored to death. But the values of the church—do good, do right, don’t drink, don’t kill anybody, no stealing, the ten commandments, don’t covet your neighbor’s wife—I don’t believe in some parts of this culture those values are being instilled. Those kids running up and down—I used to work in mobile-home parks, and we’ve got some unsavory characters there—they need their butts worn out, like I’ve gotten mine worn out.

“I think the reason for that is the breakdown of the family. Where the father and mother are not both there doing their job. I bring up my children to respect me. And I think my boy fears me, and I think that’s good, because he knows I’m not going to put up with everything. I hug him and kiss him every day. Some people say I’m right; some people say I’m wrong. I was afraid of my father. I was afraid I was going to get my behind worn out. I don’t like it any other way. People saying, ‘Yeh,’ ‘Nah’—smartmouth children—I think they’d do so much better if they worked hard for just ten more minutes every day, and if they said, ‘Yes, sir,’ ‘No, sir,’ and you whipped their ass until they said it right.

“I think it all goes back to being brought up right. Get some values back in the homes. We’re talking about blacks now. Get them to stay in the school, keep their damn butts quiet. I’d be a dictator and have this place shaped up. I’m just a law-and-order, blood-and-guts guy.”

Campbell was in his early forties or late thirties. He was short and chunky, a strong man. He wore bright colors. He talked like a man with a character to keep up; but there was no touch of humor in his voice or face.

He had seen the black area of Jackson spread. And he had made money out of that, buying from fleeing whites and selling at a profit to the blacks moving in. There was one year when he had sold ten houses like that, and had made $60,000.

“That wasn’t bad. I was profiteering. I ought to be shot.”

I wasn’t sure what was “character” and what was real. And then I said, “Campbell, what do you understand by the word ‘redneck’?”

And the man was transformed.

He said: “A redneck is a lower bluecollar construction worker who definitely doesn’t like blacks. He likes to drink beer. He’s going to wear cowboy boots; he is not necessarily going to have a cowboy hat. He is going to live in a trailer some place out in Rankin County, and he’s going to smoke about two-and-a-half packs of cigarettes a day and drink about ten cans of beer at night, and he’s going to be mad as hell if he doesn’t have some cornbread and peas and fried okra and some fried pork chops to eat—I’ve never seen one of those bitches yet who doesn’t like fried pork chops. And he’ll be late on his trailer payment.

“He’s been raised that way. His father was just like him. And the son of a bitch loves country music. They love to hunt and fish. They go out all night to the Peal river. They put out a trot line—a long line running across the river, hooks on it every four or five feet. They bait them with damn old crawfish, and that line’ll sink to the bottom, and they’ll go to the bank and shit and drink all night long and they’ll get a big fire going. They’ll check it two or three times in the night, to see if they’re getting a catfish. It’ll be good catfish. These redneck sons of bitches say that they’ll rather have one of these river catfish than one of those pond catfish. They say it’s got a better taste.

“You know, I like those rednecks. They’re so laid back. They don’t give a shit. They don’t give a shit.”

“Is that because they’re descendants of pioneers?”

Advertisement

“There’s no question about it. They’re descendants of pioneers. They’re satisfied to live in those mobile homes. I never knew how my father was so cultured. If you saw the place he came from—he came from the most absolute, the most desolate place in the woods on the Mississippi-Alabama border. The rednecks have the pioneer attitude all right. They don’t want to go to the damn country club and play golf. They ain’t got fifteen damn cents. And they’re just tickled to death.

“They’re Scotch—Irish in origin. A lot of them intermarried, interbred. I’m talking about the good old rednecks now. He’s going to have an old eight-to-five job. But there’s an upscale redneck, and he’s going to want it cleaned up. Yard mowed, a little garden in the back. Old mama she’s gonna wear designer jeans and they’re gonna go to Shoney’s to eat once every three weeks.”

I had seen any number of those restaurants beside the highways, but had never gone into one. Were they like McDonald’s?

Campbell said, “At Shoney’s you’ll get the gravy all over it. That’s going to be a big deal. They’ll love it. I know those sons of bitches.

“If he or she moves to north Jackson he’d be upscale. He wouldn’t be having that twang so much. But the good old fellow, he’s just going to work six or eight months a year. He’s going to tell his old lady, ‘I’m going to work.’ And he ain’t going. If it rains, he ain’t going to work—shit, no. He’s going to go to the crummiest dump he can find, and he’s going to start drinking beer and shooting pool. When he gets home there’ll be a little quarrel with his wife, and he’ll be half-drunk and eat a little cornbread and pass out, and that’s the damned truth. And she’ll understand because she’s so used to it.

“She doesn’t drink. It’s normally the redneck guys who drink—whiskey or beer. She’s got some little piddling job. She’s probably the basis of the income. She’s going to try to work every day. But he’s always waiting for the big job at fifteen dollars an hour, which is never going to come around. One time he had a union job at twelve dollars an hour. And he thinks that’s going to come back. He’ll be waiting fifteen years for another twelve-dollar job. And he won’t get it unless he gets off his ass and goes to Atlanta, Georgia, or Nashville—some place that’s hot. It’s sure not hot around here. But he’s so damn satisfied. The son of a bitch’s so damn satisfied. When he gets the four-dollar job: ‘No, I got something else to do.’ I could give five guys a job today, minimum wage. Three-thirty-five an hour. But I wouldn’t find five sons of bitches if I looked all damn day long. ‘You want to work for $3.35?’ ‘No. Not going to work for no $3.35 son of a bitch.’

“So he’s going to be making six dollars on an average, six to six-and-a-half an hour. And just for six to eight months a year. You see he doesn’t want to work all day long. He’s satisfied by getting by. They don’t like to be told what to do. It’s the independent spirit. It’s the old pioneer attitude. ‘I’ve got enough to eat, drink, and a little shelter. What more do I want?’

“Religion? They’ll go to church when the wife beats the hell out of him. But he’s not going to put on a coat and tie or anything. He won’t do it. He’ll kick her ass.

“They’re not too sexual. They’d rather drink a bunch of old beer. And hang around with other males and go hunting, fishing. We’re talking about the good old rednecks now. Not the upscale ones. They’ve got the dick still hard. That’s damn true.

“The rednecks are about 60 to 65 percent of the white population. I’m running the good old rednecks and the upscale rednecks and a whole bunch of lower-middle-class rednecks. They have the same old attitude as the black people. Daddy is home a little more often. But they’re tickled pink that they ain’t got nothing. You wouldn’t believe.”

I asked about the dress, and especially the cowboy boots. Why were they so important?

“It’s the image they have to project. They’ll have an old baseball hat with the bill turned down just so. They won’t have the cowboy hat. They want that particular redneck style. They want people to know that they don’t give a damn. They want people to know: ‘I’m a redneck and proud of it.’

“What you must put in, and make sure you do, is them sons of bitches love contry and western music. It’s down-home music. It’s crying music. Somebody got killed in a truck. Or a train ran over somebody. Or somebody ran away with somebody’s wife.

“Presley is a redneck like you wouldn’t believe. He’s a double redneck. Some of the women here would whip your ass for saying it. I’m probably a redneck myself.”

And when he said that, Campbell won me over.

He said, “I just dress differently. Polo shirt and Corbin slacks.”

I liked the concreteness of Campbell’s details, the brand names, the revelation of a fashion code where I had just seen bright colors.

Abruptly, then, he went off on another tack. “If my father hadn’t worked so hard—and I know that was important. To work hard and try and do good.”

I got him back to the subject of redneck sex.

“If they’re young they got it hard. But the older they get they drink more, and then they don’t care about it anymore. And she’s just there, getting some clothes washed down in the laundromat once a week. Sit down and watch it and smoke some cigarettes—that’s right, that’s what she will do.

“I’ll tell you. My son ain’t gonna fool with a redneck girl in Rankin Country. Can’t hide it. Everybody knows everybody else. And I’ll tell you something else. They talk different. And I want my children to stay in their social strata, and that’s where they’ll stay. I would say, ‘Keith, you weren’t brought up like that. You get your ass out of that. You’re way above that, and we’re going to stay way above that.’ But Keith’s all right. He wants to dress nice; he wants to look good; he wants to make money. We run in the northeast Jackson crowd. That’s supposed to be upscale.”

I said, “But beauty is beauty. A beautiful woman is going to win admirers anywhere.”

“Beauty is beauty. But when she opens her mouth and starts talking and she says she lives in Rankin County—uh-uh—that’s the end of any charm. But that case will probably never happen with me. It will never happen with my son because he already knows what a redneck is. You know what the word comes from? The back of a man’s neck is red from the sun.”

But something happened—somebody came into the room, someone asked a question; and Campbell didn’t finish the thought. It was finished for me some days later when I heard from an old Mississippian that the word “redneck,” when he was a child, was not a pejorative; was the opposite, in fact, and meant a man who lived by the sweat of his brow; and that it was only in the 1950s, when the frontier or pioneer life was changing, that the word began to have unflattering associations.

Campbell said: “I admire them for their independence. But it’s not right for the society now. No question about it. It was great a long time ago. But not now. You can’t get business done in a modern city with that kind of mentality. We got to change that redneck society and that black society, or the wealth is going to be just in the few hands that it’s always been in. As far as I’m concerned I hope it stays like that. I ought to be shot.”

He came back from that political pitch. He said: “Rednecks like four-wheel drives. Four-wheel-drive pick-up trucks. They can run down everywhere through the swamps. And some of them like an old beat-up van, half-painted. Half-painted, because he’s going to fix this side, but he’s never going to get around to the other side. He’ll drive that son of a bitch forever, until it falls apart, or gets a flat tire, and he’ll just leave it then. He won’t have a spare, you see. And he’ll come back that afternoon and get it fixed. He’ll get one of his buddies to get an old tire, and they’ll go and fix it. The sons of bitches can fix anything on a car. Them bastards can do anything. They can drag that car to the side of the highway and jack it up and fix it on the spot.”

The morning was over. Campbell had a business lunch. He was going just as he was, in his bright, horizontally striped green and yellow jersey, the stripes of varying width. But he had so enjoyed talking of redneck life; it had brought back so many memories of his own “crazy” youth, and prompted so many yearnings, that he wanted to talk a little more, and he promised to come again in the afternoon, after his lunch, and before a business trip to Florida.

He telephoned after his lunch. I asked how it had gone.

“I’m smelling like hell. A whole load of garlic at lunch. But made money. Unusual, a business lunch where I actually made money.”

We met later, in a hotel bar. He had been drinking to celebrate his deal. His eyes were moist, a little bloodshot. He had spoken deadpan in the morning; and he spoke deadpan now. But the drink made his speech chaste. He spoke no swear word, no unnecessary or blaspheming intensive.

I said I had been thinking over what he had said about the rednecks. From the way he had described them, I thought of them as a tribe, almost an Indian tribe, free spirits wandering freely over empty spaces. But weren’t they now a little cramped, even in Mississippi?

Campbell said: “It’s a nice life, but it depends on a natural life being available. I would say that if those rednecks didn’t have these natural surroundings in Mississippi—because the outdoor thing’s their favorite pastime—they would be very bored. And hunting rights are becoming so valuable now they’re going to be forced out of the market within five years. We’ve got a lot of people coming up this far north now from Louisiana, because we have a lot of deer, big deer, and they’re paying big prices for the hunting rights. I bet you couldn’t drive forty-five minutes out of Jackson without finding land that wasn’t leased. It’s going to have a ‘Posted’ sign: ‘This land is leased by So-and-So Hunting Club. Don’t Trespass.’ One day there’s going to be a killing about it, I tell you. They’ve already had a couple of killings in the state. Duck hunting especially—it’s so competitive in the Delta, so valuable, so expensive to get a lease up there. You’ve got to have a lot of money. It will cost you about three thousand dollars a year to hunt duck. Though duck hunting is more of a gentleman’s sport. Those rednecks are more meat-hunters.

“Still, there’s a lot of land in Mississippi. They’ll poach on somebody. Otherwise they’ll just be beer drinkers and have no place to go and nothing to do. It’s what’s worrying me about the rednecks. They’re not adapting, and they’re being left behind. As the population grows it’s going to be more and more expensive for them to go out hunting, and they’re not going to be able to afford it.

“At the moment they have some dog clubs. They get in real cheap somewhere and they’ll do some deal, some deal with somebody’s family—fifteen, twenty, thirty guys in a family deal, cousins all of them on family land. All getting together ten or twelve times a year. And they’ll have a ball.”

“What about the women? Do they go out on those trips?”

“They just sit at home. They’re worrying about where the next sack of potatoes is coming from. But they can live on one hundred dollars a week. Cheaper than you and I. And they’re not skinny. Some of them are big and fat. What am I saying? They’re all big and fat.

“After lunch, you know, I went back to the office. The secretary’s a redneck woman. I told her about our talk this morning. About the rednecks and the frontier mentality. Telling her it’s not so great these days, you know. Different times. And she said, ‘You know, Mr. Campbell, at one time I used to be envious of you. I wanted what you had. But now I feel I’m just different. I’m just born into it. I ain’t got nothing, and I know now I ain’t going to have nothing.’ I said, ‘It’s because you ain’t got the right kind of husband. Why don’t you kick your husband’s ass?’ And she said: ‘Oh, Mr. Campbell, I can’t do that. He’s just an old redneck.’ And her children are just like him.

“Presley, he was the all-time neck. And that fellow there, that fellow at the desk with the long hair and beard.”

He was talking about a man with a red plaid shirt hanging out of his trousers. This man was walking delicately on the floor, as though nervous of slipping on it with the leather soles of his cowboy boots.

Campbell said, “He’s probably thinking, with that hair and beard, that he’s God’s gift to the world. But he’s just a neck. He’s as lost as a goose. He’s never been on a tiled floor in his life. He’s come in here thinking it was another motel. He doesn’t know what to do. He’s just moping around here. ‘Oh shit, where am I?’ ”

Art hallows, creates, makes one see. And though other people said other things about rednecks; though one man said that the best way of dealing with them was to have nothing to do with them; that their tempers were too close to the surface, that they were too little educated to cope with what they saw as slights, too little educated to understand human behavior, or to understand people who were not like themselves; that their exaggerated sense of slight and honor could make them talk with you and smile even while they were planning to blow your head off; though this was the received wisdom, Campbell’s description of their mode of living made me see pride and style and a fashion code where I had seen nothing, made me notice what so far I hadn’t sufficiently noticed: the pick-up trucks dashingly driven, the baseball caps marked with the name of some company.

The next day, a Saturday, there was a crowd in the hotel and the restaurant across the parking area from the hotel. And as if in fulfillment of Campbell’s description of the redneck style, three men got out of a dented and dusty car and opened the car trunk to take out their redneck boots, which were there in the trunk. They had arrived in gym shoes. They took off their gym shoes and put on their cowboy boots before going into the hotel. One among them was opening a bottle of beer with his teeth. I felt now, after Campbell, that the man doing that very redneck thing perhaps needed a little courage. Perhaps, entering the hotel and walking on the tiled floor, he was going to feel “as lost as a goose.”

For some days Campbell’s words and phrases sang in my head; and I spoke them to others. One afternoon I went to a farm just outside Jackson. Someone there, knowing of my new craze, came to me and said, “There are three of your rednecks fishing in the pond.” And I hurried to see them, as I might have hurried to see an unusual bird, or a deer. And there indeed they were, bareback, but with the wonderful baseball hats, in a boat among the reeds, on a weekday afternoon—people whom, before Campbell had spoken, I might have seen flatly, but now saw as people with a certain past, living out a certain code, a threatened species.

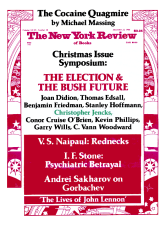

This Issue

December 22, 1988