In response to:

Black Crime, White Racism from the March 3, 1988 issue

To the Editors:

Thank you for Andrew Hacker’s excellent article “Black Crime, White Racism.”

Segregated living is one of the facts of life in the United States that hit me most during various stays, mainly in the San Francisco Bay Area between 1967 and 1981.

Due to the enormous rent increase in Berkeley we had the interesting experience to live in a somewhat mixed neighbourhood in North Oakland for over a year in 1980/81.

It was strange.

Bobby Seale, Black Panther (loud) speaker of the 60s showed up, silk suit, soft voiced, running for mayor of Oakland.

He attracted an all black audience. Except for the curious German no one of the white neighbours came close to listen.

They did not care—or perhaps they did not dare. I don’t know. It was the same everywhere. I was the only white at all the black political rallies I went to.

What a paradox situation:

In 1983 Oakland was named the most integrated city in the U.S. (Brenda Payton in The Progressive, January 1988).

Yes, your service sector is integrated—your life is not. Your life is split—black and white in public, all white private.

Most everyone you meet doing your daily business is black.

Your mailman is black, your bus driver is black, the people at the gas station are black, so are the friendly people at your bank, your store—except for their bosses.

If you are on medicare—or liberal—even your doctor is black.

Our daughter was born with the friendly and gentle help of a black doctor—actually he was not really black, more brownish, living up to his name, Blanchette. He was a very good doctor—as were his black, black colleagues my wife had to consult. Well, being a white, white blue-eyed blond German, she did have problems facing these black, black doctors at first. It was their professional excellence that did convince her—rationally, not emotionally.

To come back to the paradox:

We trusted black doctors, our landlady was black yet we did not have any personal relations with any black person.

There were no blacks at the numerous parties, picnics, trips, etc. we were invited to.

No blacks at the favorite neighbourhood bar, no blacks around in the various state and national parks we visited, weekends, recreational activities were all white—as were most of the political meetings I went to in Berkeley, except for some election meetings.

Black and white integration at work, in your public life, your service sector, yet total segregation, apartheid, in your private life.

It is a miracle to me that this paradox living situation does not cause more emotional confusion with blacks—and whites.

A psychiatrist would expect to find a split personality in a split living situation.

This adds one more question to Andrew Hacker’s article:

How will white Americans fare in their country when they fully realize it’s not their own any more?

Will white frustration replace white domination—or is there a chance to reduce alienation for both black and white Americans?

To be honest:

Our experience in Oakland did not leave us overly optimistic.

Eight years of Reaganism for sure did not help.

I am looking forward to perhaps finding more hope and insight in Andrew Hacker’s new book.

Heinz H. Spiess

Munich, West Germany

Andrew Hacker replies:

In reply to Gilbert Johnson, my disappointment concerned the small number of black persons holding high positions in white organizations. The reason, I emphasized, is not a shortage of capable candidates, not a lack of potential for handling responsibility. Rather, decisions about which blacks—and how many—will be promoted are made by white superiors. And those decisions involve not only individual merit, but also whether too visible a black presence will jeopardize the organization’s reputation in the white world.

I should correct a slip concerning the source of the statement by Jefferson on racial equality I quoted in my article. It is to be found not in his Notes on the State of Virginia but rather in a letter to Benjamin Bannaker, written in 1791.

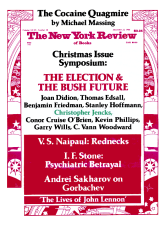

This Issue

December 22, 1988