In mid-February 1989 a group of six senior American specialists on the Middle East, including three former high-ranking US government officials, went to Tunis for three and a half days of intensive talks with high PLO officials, among them Yasser Arafat and Abu Iyad, the second highest ranking official in the PLO, in an effort to determine if the PLO was serious about its newly proclaimed peace initiative, which calls for an independent Palestinian state alongside Israel.* The members of the group agreed that if they found the PLO to be serious about peace, they would then present their views on how the Palestinian–Israeli peace process could be encouraged. This was one of the few extensive meetings of American Middle East specialists with Mr. Arafat and the other leaders of the PLO to take place; its outcome was, in my view, encouraging.

As the only Jew in the American delegation, I had prepared for the trip by asking a number of other Jews, including Israelis both inside and outside the Israeli government, Americans involved in Jewish community relations councils and other Jewish organizations, as well as rabbis and fellow Jewish academics, to suggest the issues they would raise if they had the opportunity to speak to PLO officials. From my interviews I compiled a list of twenty-one questions, the most important of which I planned to raise with the PLO officials.

The first opportunity to raise these questions came the night we arrived, when Yasser Arafat himself was host at a dinner for the delegation (I had informed the Palestinians in advance that I observed the Jewish dietary laws, and so I was always able to get suitable food). Arafat, in our meetings, turned out to be a very engaging man who has in common with some Israelis a habit of clicking his tongue just before he says no. He served some of the food to us himself and when we left at midnight after almost four hours of talks, he escorted us to our cars, although it was raining outside and he had three more interviews (one with Mike Wallace of CBS) still awaiting him inside.

At the beginning of the evening’s discussion, we talked about the peace process, and Arafat’s statements at first seemed to me simplistic and defensive when he was challenged. He said that while the PLO was talking to individual Israelis to promote the peace process, what was needed was “another Eisenhower” to pressure Israel, America’s “naughty child.” When he was told by the American delegation that another Eisenhower was extremely unlikely, he seemed somewhat taken aback. The most heated part of the discussion came when, after introducing myself as an American Jew, I pointed out to Arafat that while the Palestinian National Council statement of November 1988 and Arafat’s speech at the UN meeting in Geneva in December 1988 were positive steps, much more had to be done to convince Israelis and American Jews that the PLO was indeed serious about peace.

I raised three main points with Arafat: 1) that the Palestine National Covenant, which calls for Israel’s destruction, had to be changed (this was at the top of the list of virtually every Jew with whom I spoke); 2) that Abu Iyad should explicitly repudiate remarks being attributed to him about a policy of two stages—first to get a West Bank/Gaza Palestinian state and then to use it as a base to attack Israel; and 3) the PLO should explain in detail the measures that a Palestinian state would take to limit its armaments, for example, and to convince the Israelis that it would not be a military threat to Israel.

Arafat reacted emotionally and a bit angrily to my assertions, claiming that Palestinian as well as Israeli security had to be assured in any settlement and listing the massacres carried out against the Palestinian people. In this list he mentioned not only what he termed Israeli-supported actions like Sabra and Shatila, but also the actions of his “Arab brothers” such as Jordan and Syria. Once he calmed down, however, and I pressed the subject, he noted that when PLO-Israeli negotiations began, the PLO would be happy to discuss any kinds of security arrangements the Israelis wanted, including having a multinational European force on the border between the two states, Israel and Palestine, and he added that this force could remain in place as long as the Israelis wanted it to.

We then had dinner and Arafat became much more genial. He noted that he had heard what I had said about further PLO steps to reassure the Israelis and would think about them, but noted in respect to the Palestine National Covenant that he had two problems. First, to change it would alienate Islamic fundamentalists who are already highly critical of what he has done, and who claim that all of Palestine is sacred Islamic territory, and not his to give away. Secondly, he complained that the Herut party (a component of Likud) still had its charter, which calls on Israel to gain both banks of the Jordan, that is, not only present-day Israel and Gaza and the West Bank, but also the state of Jordan. Moreover, he noted, the Israeli flag has two blue lines which indicate that the natural borders of Israel run from the Nile River (in Egypt) to the Euphrates River (in Syria and Iraq). I explained that the flag’s motif originated in the Jewish Talit (prayer shawl), not in the hope of conquering the territory from the Nile to the Euphrates. From this incident, as well as others during our four days of discussions with the PLO leadership, I concluded that a dialogue between the Israelis and the PLO is necessary if only to clear up the misconceptions that have accumulated over the forty years of Israeli–Palestinian hostility.

Advertisement

After dinner Arafat outlined his concept of peace, which included economic, diplomatic, and cultural relations between Israel, the Palestinian state, Jordan, and Lebanon, on the model of the European Benelux system (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg). Since I and a number of others, both Israeli and Palestinian, had long been calling for just such an arrangement as part of the solution to the Arab–Israeli conflict, I considered this a major step.

In further discussions, Arafat indicated that an international conference could come at the end of the peace process, and that Israeli–PLO negotiations could take place before such a conference was held. He also noted that he was opposed to the plan for elections on the West Bank and Gaza as currently proposed by the Israeli government because he saw it as an attempt to split the Palestinians living in the occupied territories from the PLO and Palestinians living in the Palestinian Diaspora. He saw the plan also as a means of stalling for time at the stage of a very limited degree of Palestinian “autonomy” instead of allowing full Palestinian “self-determination,” which means an independent Palestinian state. He did say, however, and other Palestinian spokesmen later developed the idea further, that elections on the West Bank and Gaza could be a positive step if they were connected to a genuine peace process; that is, if they would eventually lead to a Palestine state.

By the time the discussion turned to terrorism, Arafat was in a particularly receptive mood. When I suggested that he agree to proclaim that he would punish any Palestinian terrorist attacking Israel from the future Palestinian state and would expect that the Israeli government would punish any Israeli terrorist attacking the Palestinian state from Israel, he nodded his head, said “why not?” and told one of his aides to write that down. (A subsequent discussion of the definition of terrorism with the number two man in the PLO, Abu Iyad, clarified the definition. Abu Iyad stated that the PLO already prohibited attacks on Israeli civilians inside and outside Israel proper, but did not consider the intifada a form of terrorism since a population under occupation was rising up against an occupation army. Our delegation, however, said that we thought that throwing Molotov cocktails was both inhumane and politically very counterproductive in both Israel and the US.)

As the evening ended Arafat came over to me, shook my hand, and said “We need to dialogue not only with the United States but with our cousins [Jews] too.” The importance of American Jews in the PLO dialogue with Israel was also discussed later with PLO leaders. I pointed out to them that just as they did not want the United States or Israel to try to drive a wedge between the Palestinians on the West Bank and Gaza and those in the Diaspora, so too the PLO should not try to drive a wedge between the American Jewish community and the state of Israel. They assured me that this was not their goal and they said to me several times that they hoped American Jews would be a bridge to Israel, that they would tell the Israelis that the PLO was sincere about peace, and that Israel should enter a dialogue with the PLO. One of Arafat’s advisers, Bassam Abu Sharif, bluntly told me, “We would much prefer to talk to the Israelis than with you, but until they are willing, you will have to do.”

All the Palestinian leaders with whom we talked showed great flexibility in their approach to the peace process and shared Arafat’s version of what a settlement with Israel would look like. They also emphasized the need for an Israeli–PLO dialogue leading to a comprehensive peace conference in which all the Arab states involved in the conflict, including Syria, would participate. (Arafat said he could not be “another Sadat” and make a separate peace with Israel, but that if Syria chose to decline the invitation to the conference, that would be Syria’s problem.) Nonetheless the Palestinian leaders expressed different views on a number of other issues. They differed among themselves on whether or not Shamir would be able to stay in power for his full term of office, the relative strength of the Labour party in the Israeli political system, and whether time was working for or against the Palestinian cause.

Advertisement

I came away from the discussions cautiously optimistic. I think the PLO genuinely wants to talk to the Israelis and that they are seriously interested in having their Palestinian state, once it is established, live in peace alongside Israel. Indeed, a number of PLO officials offered eventually to make the new Palestinian state Israel’s bridge to the rest of the Arab world. But they feel that they made a major concession in November 1988, when they came out for the two-state solution, and that it is now the Israelis’ turn to respond, particularly since, they claimed, major political problems within the loosely federated PLO would result if the organization made further concessions to Israel—such as formally abolishing the Covenant—without having received Israeli concessions in return. My colleagues and I strongly expressed our opinion that—in view of the internal situation in Israel, and the suspicions many Israelis still harbor toward the Palestinians—further PLO concessions and clarifications would have to be made if the PLO hoped to convince the Israelis to enter into a serious political dialogue with the PLO.

On the final day of our discussions, I left my list of twenty-one questions with the PLO leader, who promised to study them carefully. If they respond to the questions to the satisfaction of the Israelis, the peace process may move a step forward.

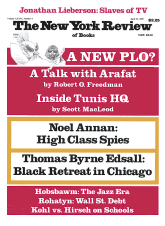

This Issue

April 13, 1989

-

*

Aside from myself, the delegation included William Quandt, Harold Saunders, and Helena Cobban, of the Brookings Institution; Hermann Eilts, former ambassador to Egypt; and Karen Dawisha, professor of government at the University of Maryland.

↩