In response to:

Tolstoy in Embryo from the March 2, 1989 issue

To the Editors:

I am grateful to Professor Adams for his kindly review of my book on Bunyan [NYR, March 2]. But may I put the record straight on a couple of points? First, he points out, rightly, that we know little about Bunyan’s military service, though it is now established that he was in the Parliamentarian army from the age of sixteen to eighteen-and-a-half, serving in the garrison of Newport Pagnell. I collected all the evidence I could find about Newport Pagnell in those years, using especially the correspondence of its commanding officer. From this it was clear that Newport was a hotbed of seditious religious and political talk and action in the two years after victory when the troops had nothing else to do. There is no direct evidence of Bunyan’s participation in these exciting discussions. But his autobiography tells us of several years struggle with Ranter and libertine ideas before his conversion in 1653. These were the ideas which had circulated in Newport Pagnell, and Bunyan repeats later some of the stories told by its commanding officer. So it is at least probable that the teenage Bunyan became acquainted with these ideas then.

They haunted him for the rest of his life. Ranters and their like are condemned in Grace Abounding, The Pilgrim’s Progress, The Holy War and Mr. Badman. In a commentary on Genesis on which Bunyan was working when he died he is still wrestling with them. Your reviewer criticizes me for using evidence from Bunyan’s later writings to illuminate his earlier experience: I was trying to suggest, from the continuity of Bunyan’s agitation, that these ideas worried him throughout his life.

Your reviewer is also right to criticize the overemphasis on the fact that Bunyan was a tinker in the book’s title. For the English edition I chose a title which emphasized the sedition and factiousness attributed by his contemporaries to Bunyan and his church. I am sorry the American publishers changed this title. And it was Bunyan’s enemies who stressed Bunyan’s mean status as a tinker: he preferred to emphasize his lack of formal education, asserting that he got his ideas from no books except the Bible.

Christopher Hill

Oxford, England

Robert M Adams replies:

That Bunyan struggled early and late against Ranter and libertine ideas I did not mean to deny; I remain strongly of the impression that he was more religiously than politically inclined. That was why I demurred at the notion that he was strongly impressed by people like Harrington, Clarkson, and Winstanley (whom we can’t be confident he read), and called attention to his political innocence in coping with the duplicities of James II at the end of his life. Lenin might have called him, I think, “A good man fallen among Baptists.”

One passing consequence of this contretemps has been to send me back to read over several of Professor Hill’s earlier books to see if they were as good as I recalled their being. An apology, I’m afraid, is in order; they are better, even better, than I remembered them.

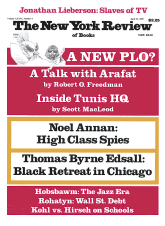

This Issue

April 13, 1989