In response to:

Unkind to Animals from the February 2, 1989 issue

To the Editors:

Anthropomorphism has a long history in human thought and culture. It is very attractive to interpret incomprehensible natural forces and organisms as expressing human emotions and behavior. Despite this attraction, it is a mistake to base social policy on such a simpleminded understanding of the world. The attribution to animals of “rights” gives them human qualities that they do not possess; it makes as much sense to speak of animal “arts” or animal “science.” Rights, arts, sciences, all of these and many other concepts are uniquely human in both origin and application.

Human treatment of animals is a matter of human ethics and morality, and should be debated as such. I prefer such debate to be rational rather than emotional: in particular I am disturbed by the repeated use by Peter Singer in these pages of photographs of suffering animals. I am sure that someone on the opposite side of the issue could easily provide photographs of a child suffering from a disease cured through scientific research which at least partly involved animals. Is this conducive to rational discourse? I think not.

Finally, I must disagree with Peter Singer’s opinion [“Unkind to Animals,” NYR, February 2] that young reseachers should avoid medical research involving the use of animals. He says

I hope that these young researchers…turn instead to tasks such as health education and the distribution of our existing medical techniques to those places where the need is greatest. In that way they will make a greater contribution to human health than they would ever be likely to make by experimenting on animals.

Considering the humans already dead from the scourge of AIDS, and the numbers yet to die, I find this cavalier willingness to turn away from the mainstay of medical research and the best hope for curing many diseases chilling.

Berkley A. Lynch

The Rockefeller University

New York City

Peter Singer replies:

Berkley Lynch makes three points, and gets them all wrong.

First, my position in regard to animals is not based on any attribution of “rights” to them. I have made this plain on several occasions, including my New York Review essay “Ten Years of Animal Liberation” [January 17, 1985] and the exchange with Tom Regan that followed [April 25, 1985]. But those who do attribute rights to animals will have no difficulty in dealing with Lynch’s claim that rights are uniquely human both in origin and application. No doubt the concept of rights is held only by humans, but why should it be applied only to humans? If a human infant has a right not to be used in a painful experiment, why should not a dog, at a similar or higher mental level, have the same right? Historically, the concept of rights appears to have its origin in European civilization, but that is obviously no reason for denying its application beyond people of European descent. So the origin of the concept is irrelevant to its application, and we need reasons, not mere assertions, if it is not to be applied to all beings with relevantly similar capacities, irrespective of race, sex, or species.

Second, the choice of illustrations for my publications in The New York Review has always been that of the editors. I have never supplied the editors with photographs or made any suggestions about what kind of illustrations should be used. But I see nothing objectionable about the use of a photograph to illustrate how animals are treated in laboratories. It is, of course, always much more speculative whether a particular patient would or would not have been cured had animal experimentation not taken place; and whether, had the resources that go into animal experimentation gone elsewhere, that patient or other sick people might have been cured.

And this brings me to Lynch’s final point. The comment that he finds so “chilling” was based on the fact that the major health problems of the world largely continue to exist, not because we do not know how to prevent disease and keep people healthy but because no one is putting enough effort and money into doing what we already know how to do. The diseases that ravage Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the pockets of poverty in the industrialized West are diseases that, by and large, we now know how to cure. They have been eliminated in communities that have adequate nutrition, sanitation, and health care. It has been estimated that 250,000 children die each week around the world, and that one quarter of these deaths are by dehydration due to diarrhea. A simple treatment, already known and needing no animal experimentation, could prevent the deaths of these children.

There is, incidentally, a double irony in Lynch’s reference to AIDS. First, the points I have just made are drawn from a New Scientist editorial that has nothing to do with animal experimentation, but raises questions about the resources now going into AIDS research (“The Costs of AIDS,” New Scientist, March 17, 1988, p. 22). Secondly, Robert Gallo recently admitted that French scientists may be making better progress toward an AIDS vaccine because they are working directly with human volunteers, while Americans are working with chimpanzees. Gay activist Larry Kramer has endorsed this call, saying “Let us be your guinea pigs.” (See The Washington Times, April 19, 1988, and Science, Vol. 239, 1988, p. 1087.) In view of these facts, one has to ask: Is Berkley Lynch really concerned about preventing human suffering? Or about continuing the animal research conducted at Rockefeller University?

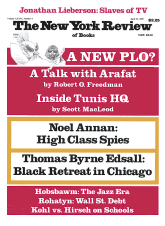

This Issue

April 13, 1989