In response to:

Unkind to Animals from the February 2, 1989 issue

To the Editors:

In his recent review of my book Animal Liberators philosopher and animal rights advocate Peter Singer rejects my anthropological perspective on the animal rights movement as applying a “distorting lens on the subject of the research.” Singer’s umbrage at finding himself “anthropologized” is amusing, but his review obscures the insights offered by an anthropological analysis of this important topic.

Indeed, anthropology is an essential tool in digging through the layers of cultural meanings assigned historically to blacks, women and animals. In his writings Peter Singer frequently draws an analogy between the liberation struggles of oppressed humans and animal liberation. Although at first glance it may seem reasonable to compare the liberation of subjugated minorities and women to the liberation of animals, closer scrutiny reveals an important subtext in Singer’s efforts to do so.

Arguing that we cannot base our objections to racism or sexism on the grounds of absolute equality between races or sexes, Singer writes in Animal Liberation (all quotes are from the 1975 Avon edition):

There is a second important reason why we ought not to base our opposition to racism and sexism on any kind of actual equality, even the limited kind that asserts that variations in capacities and abilities are spread evenly between the different races and sexes; we can have no absolute guarantee that these capacities and abilities really are distributed evenly without regard to race or sex, among human beings. So far as actual abilities are concerned there do seem to be certain measurable differences between both races and sexes [p. 4].

Singer’s logic is that genetically based inequality is no excuse to deny moral equality between blacks and whites; it is equally inexcusable as a justification to deny moral equality between animal and human. In his rush to find a perfectly parallel argument for animal liberation, he suggests that genetic differences in mental and other abilities may exist between races as they do between human beings and animals.

Buried shallowly beneath Singer’s recipes for tofu and other vegetarian specialties is an unsavory stew of Western cultural assumptions about the relationship of races and sexes with a light sauce of apology. Sixty-five pages of text and illustration in the 1975 paperback edition of Animal Liberation are devoted to an extensive attack on animal experimentation, but less than a paragraph examines the contention that “important differences” between the races and sexes may be genetic.

I chose to examine the passionately antivivisection stance of the animal rights movement because this is precisely where the conflict between the majority of people concerned about animal welfare and the animal rights movement is most intense. Reasonable people, myself included, want to see animal abuses exposed and abolished. Who would not agree with the movement in its condemnation of cruelties in factory farming, its position on the humane treatment of pets, and its protest of the brutality and unfairness of hunting? What is worth studying about the animal rights movement is not what it has in common with humane, ecology and consumer groups, but what it does not.

In his review of The Use of Laboratory Animals in Biomedical and Behavioral Research, which follows that of my book, Singer says he is glad that the animal rights movement has discouraged many young researchers from pursuing animal research. The movement’s chilling effect upon future research with animals should be examined carefully. A UC Davis research virologist and veterinarian, Tilahun Yilma, has recently developed a vaccine which prevents a fatal disease affecting hundreds of thousands of cattle in East Africa. The vaccine was developed using research animals—far fewer in number than die annually of the disease. This vaccine will be produced by tribal herders, who have learned to inoculate their own animals and to use the scabs which form as a source of material for further inoculation. The potential repercussions of Singer’s, and the movement’s, smug ethnocentrism are frightening. Singer’s unmitigated indictment of animal research may one day prevent the kind of research that developed this vaccine.

Some of the most promising research on the prevention of death from AIDS involves the use of animals. For the millions of people who will die of this disease, it is not a light matter that, included with the many reasonable assertions of the animal rights movement is a darker impulse towards the total suppression of all animal research, regardless of its potential merit.

The impact on social action of Singer’s position may be seen in academic communities across the land. Middle-class white urbanites and college students mass on the Berkeley campus for passionate demonstrations against the use of animals in research, while several miles from the Berkeley campus is a largely black community in which the life expectancy of adults has recently fallen and infant mortality rates are higher than in many third world countries. Those who pour their efforts into antivivisection protest are absenting themselves from the front lines of human reform, despite Singer’s claims to the contrary. My book, Animal Liberators, offers some conclusions about why so many have turned from the social horrors which surround us to an obsessive focus on animals.

Susan Sperling

Berkeley, California

Peter Singer replies:

I cannot see why anyone should be surprised that in a book entitled Animal Liberation I spent a lot more space examining animal experimentation than I did on the contention that important differences between the races and sexes may be genetic; that was simply not the subject of that particular book. In another book (Practical Ethics, Cambridge University Press, 1979) I devoted much more space to the issue of racial and sexual equality, as well as to a number of other questions concerning human well-being.

But if Ms. Sperling likes the game of finding “subtexts” in what people do not say, I am willing to play. My review of her book said that her claims about the nature of the animal liberation movement were based on deep ignorance about what the movement is really about, that her “research” was done in 1984 and never updated, that it was limited to conversations with just nine people, and unsupported by any attempt to gain a more comprehensive picture of the movement, and that the book is riddled with simple errors. I also accused her of bias on the grounds that she was encouraged to carry out the work by her former graduate supervisor, an animal experimenter who has been criticized by animal activists.

What subtext can we find in Sperling’s failure to attempt to rebut at least some of these serious charges against her scholarly and professional standards?

Ms. Sperling claims that she chose to examine the antivivisectionist stance of the animal rights movement because “Who would not agree with the movement in its condemnation of cruelties in factory farming…[etc.]?” The answer, as she should know, is the governments of every country in the world except Sweden, including the United States government and the governments of each of the fifty US states. All of them have the power to do something about the cruelty of factory farming, but none of them have taken any action. Indeed, they continue, through their departments of agriculture, to promote and support factory farming. If Ms. Sperling were genuinely concerned about this cruelty, she could have written a very different and much more useful book.

On the relative value of animal experimentation in alleviating human misery, including the tragedy of AIDS, I have already commented in my response to Berkley Lynch.

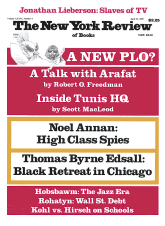

This Issue

April 13, 1989