When I began in the early 1920s to compose music for texts by Gertrude Stein, my main purpose was musical. Or let us say musical and linguistic. For the tonal art is forever bound up with language, even though a brief separation does sometimes take place in the higher civilizations, rather in the way that the visual arts will occasionally abandon, or pretend to abandon, illustration. The musical art, moreover, in its more ambitious efforts toward linguistic union, has regularly entwined itself with liturgical texts and dramatic continuities.

Now the liturgical connection has been operating successfully ever since medieval times and even earlier; but in Western Europe it regularly had bypassed the local dialects and the budding languages, remaining attached for administrative reasons to the formalistic, the far less vivid Latin. The first modern tongues to take on music liturgically (the first gesture after their doctrinal breakaways from Rome) were English and German, both in the sixteenth century. The Latin-based local idioms had made no great effort toward entering the Catholic liturgy until today’s ecumenical trend got them involved. But toward the end of that same sixteenth century, which was producing liturgically such remarkable results for English and for German, Italian musicians in Florence had begun to perfect for secular purposes (for the stage) a blending of music with language so miraculously homogenized that a new word had to be found for it. They called it opera, or “work”; and work was actually what it did, invigorating the theater internationally in a manner most remarkable. For the English poetic theater, after the times of Elizabeth I and James I, began to lose vigor at home and never seemed able to travel much abroad. But the Italian Iyric theater in less than a century had begun to implant itself in one country after another and in one language after another. It took on French with Lully in the middle seventeenth century, German in the late eighteenth with Mozart, Russian in the nineteenth, beginning in the 1840s with Glinka.*

Serious opera seems never to have felt quite comfortable, however, in English or in Spanish, languages of which the poetic style, highly florid, made music for the tragic theater almost unnecessary. Comedies with added song and dance numbers existed of course everywhere; but music rarely served in them for much more than sentiment, being too slow, hence too clumsy a medium for putting over either sight gags or verbal jokes, except in the patter songs that are specific to the genius of English.

Nevertheless, English-language composers have never stopped making passes at the opera. It is as if we bore it, all of us, an unrequited love. My own hope toward its capture was to bypass wherever possible the congealments of Italian, French, German, and Russian acting styles, all those ways and gestures so brilliantly based on the very prosody and sound of their poetry. For an American to aspire toward avoiding these may have seemed over-ambitious. But for one living in Europe, as I did for several decades, it may have been an advantage being able finally to recognize the foreignness of all such conventions and to reject them as too hopelessly, too indissolubly Italian or French or German or Russian, or even English, should some inopportune British mannerism make them seem laughable to us.

Curiously enough, British and American ways in both speech and movement differ far less on the stage, especially when set to music, than they do in civil life. Nevertheless, there is every difference imaginable between the cadences and contradictions of Gertrude Stein, her subtle syntaxes and maybe stammerings, and those of practically any other author, American or English. More than that, the wit, her seemingly endless runnings-on, can add up to a quite impressive obscurity. And this, moreover, is made out of real English words, each of them having a weight, a history, a meaning, and a place in the dictionary.

The whole setup of her writing, from the time I first encountered it back in 1919, in a book called Tender Buttons, was to me both exciting and disturbing. Also, as it turned out, valuable. For with meanings jumbled and syntax violated, but with the words themselves all the more shockingly present, I could put those texts to music with a minimum of temptation toward the emotional conventions, spend my whole effort on the rhythm of the language, and its specific Anglo-American sound, adding shape, where that seemed to be needed, and it usually was, from music’s own devices.

I had begun doing this in 1923, before I ever met Miss Stein; and I ended it all by setting our second opera, The Mother of Us All, in the year of her death, 1946. This was actually her last completed piece of writing and, like our earlier operatic collaboration, Four Saints in Three Acts, from 1927, had been handmade for me.

Advertisement

Four Saints is a text of great obscurity. Even so, when mated to music, it works. Our next opera, separated from the other by nineteen years and by a gradual return on her part to telling a story straight, was for the most part clear.

Both Four Saints and The Mother offer protagonists not young, not old, but domineeringly female—St. Theresa of Avila and Susan B. Anthony. In both cases, too, the scene is historical; and the literary form is closer to that of an Elizabethan masque than to a continuous dramatic narrative. But there the resemblance ends. The background of the first is Catholic, Counter-Reformational, baroque, ecstatic. The other deals with nineteenth-century America—which is populist, idealist, Protestant, neighborly (in spite of the Civil War), and optimistic. The saints are dominated by inspirations from on high, by chants and miracles, by orders and commands, and by the disciplines of choral singing. The Americans of The Mother, group-controlled not by command but by their own spontaneity, are addicted to gospel hymns, darn-fool ditties, inspirational oratory, and parades. Nevertheless the music of the work, or so Carl Van Vechten found, is an apotheosis of the military march.

I do not know that this is true. All I know is that having previously set a text of great obscurity, I took on with no less joy the setting of one so intensely full of meanings, at least for any American, that it has seldom failed at the end to draw tears.

For this result, my having earlier worked on texts without much overt meaning had been of value. It had forced me to hear the sounds that the American language really makes when sung, and to eliminate all those recourses to European emotions that are automatically brought forth when European musicians get involved with dramatic poetry, with the stage. European historic models, music’s old masters, let me assure you, are not easy to escape from. And if any such evasion, however minor, takes place in The Mother, that is due, I think, to both Miss Stein and myself having for so long, in our work, avoided customary ways and attitudes that when we got around to embracing them we could do so with a certain freshness.

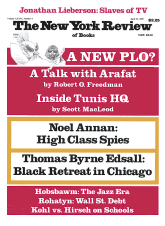

This Issue

April 13, 1989

-

*

The Florentine group (or Camerata) had begun with Greek music studies by Galileo Galilei. Giulio Caccini’s L’Euridice dates from 1600. Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo was produced in Mantua, 1607; but his later works were mostly performed in Venice.

↩