In response to:

Jerusalem: The Future of the Past from the August 17, 1989 issue

To the Editors:

As an admirer of Amos Elon over the years, both for his honesty and sensitivity, I was surprised at his portrayal of indifferent Israeli attitudes toward Jerusalem in the immediate post-independence period [NYR, August 17]. He quotes one person as saying that no one in the first 19 months of Israel’s existence even talked about Jerusalem as the country’s capital. And he goes on to imply that Israelis could have cared less about the fate of Jerusalem, or at the least its fate as the new country’s capital.

From a usually reliable and scrupulous reporter, such a misrepresentation is difficult to comprehend. Perhaps Elon was using this distortion as a scene-setter to his otherwise excellent portrayal of today’s Israelis’ passionate regard of Jerusalem. It is an effective device, but hardly worthy of Elon, for it totally miscasts Israel’s well documented desire to make Jerusalem its capital right from the beginning of the state. There is nothing new about this documentation. The official records of the State Department have been public since 1976 and they are replete with increasingly despairing reports about Israel’s determination to defy international opinion and claim Jerusalem its own. As early as Aug. 6, 1948, Macdonald, the U.S. consul general in Jerusalem, was reporting to the State Department (p. 1287, Foreign Relations of the United States) about Israel’s “demand Jerusalem be included in Jewish state.” By Aug. 18, George Marshall himself, the secretary of state who generally refused to deal with the Middle East, noted in a cable (p. 1321) that “Jews are seemingly lifting their sights and are campaigning to achieve new objective; namely control Jerusalem itself.”

From this time forward, Israel fought tooth and nail against the U.N. policy of internationalization of Israel, and against U.S. policy which supported the U.N. It increasingly asserted its right to Jerusalem, so much so that as early as April 5, 1949, if not before, the U.S. minister in Lebanon voiced the suspicion (p. 897) that Israel’s policies “make it possible for Israel to announce Jerusalem as capital of Israel with impunity.” This suspicion was reinforced when the consul in Jerusalem reported April 9 (p. 903) that Prime Minister Ben Gurion had told him that “Jerusalem is to Jews what Rome and Paris are to Italians and French respectively.” Finally, on Dec. 5, four days before the U.N.’s action on Jerusalem, Ben Gurion nearly let the secret desire out of the bag by a pointed reminder to the U.S. Ambassador (p. 1521) that Israel’s “traditional capital is Jerusalem,” adding “gravely ‘it would take an army to get Jews out of Jerusalem….” ‘

Aside from these confidential diplomatic reports, there were public statements and concrete actions by Israeli officials declaring their attachment to Jerusalem. For instance, Israel’s official record, Israel’s Foreign Relations (Vol. 1, pp. 221–2), reprints the text of a Dec. 1, 1948 speech by President Chaim Weizmann—the man Elon describes as “ambivalent” about Jerusalem—in which he says: “Jerusalem is ours…. Its restoration symbolizes the redemption of Israel…. Jerusalem is the eternal mother of the Jewish people…. Men and women of Jerusalem, fear not for the future of your city—of our city! The words of our national hymn Hatikvah will yet come true: ‘To be a free people in our own land / The land of Zion and Jerusalem.’ ”

More forceful yet were Israeli actions. As early as mid-September 1948, Israel’s Supreme Court was established in Jerusalem. On December 20, 1948, while the war was still raging, the Israeli Cabinet officially decided to move “government institutions” to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv. Israel’s parliament held its first session in Jerusalem on February 14, 1949 and three days later Dr. Chaim Weizmann took his oath of office there as Israel’s first president. By 1951, all ministries but two had moved to Jerusalem. Those staying in Tel Aviv were the defense ministry, which chose to stay there because of security concerns, and the foreign ministry which, because of international opposition, delayed until 1953 before finally making the move.

All this hardly supports Elon’s contention that it was only the December 1949 resolution by the United Nations affirming Jerusalem’s status as a corpus separatum and an international city that Israel reacted defiantly by declaring “for the first time” that Jerusalem was “an inseparable part of the State of Israel and its eternal capital.” True, Israeli officials had perhaps never officially uttered these words in public given the international concern over the fate of holy Jerusalem. But there is little doubt that a substantial number of Israelis shared that view. While Elon quotes a Cabinet secretary as saying he never heard anyone claiming Israel in the early days, scholar Michael Brecher quotes (p. 18 in Decisions in Israel’s Foreign Policy) Moshe Shapira, the original Israeli immigration minister: “For us, the State of Israel without Jerusalem is an amputated state: True, we agreed to a state without Jerusalem in 1947; but we merely waited until an opportunity arose to rectify the situation.”

That strikes me as a more representative and more sincere representation of Israeli attitudes toward Jerusalem in the 1948–9 period than Elon’s claim that it was dispassionately looked upon as some abstract “educational or cultural center.” I think Elon, with his well deserved reputation for excellence, owes history a correction and should punish himself to a thorough restudy of the available source material.

Donald Neff

Washington, DC

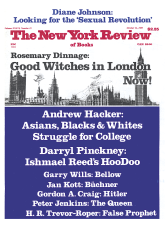

This Issue

October 12, 1989