It is common knowledge that Jimmy and Billy Carter were their legal names. It may be less commonly realized how representative of their native region this folksy naming practice is. The southern delegation in Congress during the mid-1980s, for example, included an Andy, a Billy, a Cathy, a Jamie, a Jerry, a Larry, a Lindy, and a Ronnie, all legally recorded names. When formal names do exist for popular luminaries they are often ignored or forgotten. William Franklin Graham, Jr., is a complete unknown, but Billy Graham is a household word, as are Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell.

Populistic nomenclature can become more bizarre. Men of some status bear such legal names as Bubba, Buddy, Lonnie, Sonny, and Stoney. Males are inflicted with female names and vice versa: “Frankie and Johnnie got married,” as the song has it. Both males and females often bear double given names, usually in diminutive forms, such as Billy Bob, Danny Lee, Jonnie Mae, Emma Gene, Tammy Jo, and Willie Lee, often combining a male with a female name, and as readily bestowed upon offspring of one sex as the other. The regional taste in nicknames is illustrated in the world of sports by Bear Bryant, Dizzy Dean, Mudcat Grant, Catfish Hunter, and Oil Can Boyd. Place names preserve onomastic talents of earlier times. English-speaking people have always had their way with French place names, but few have outdone Arkansans, who derived the name of their city of Smackover from the original French name, Chemin Couvert, or the Texans who created Picketwire from Purgatoire. Few novelists would be so bold as the South Carolinians who placed Slabtown on the map.

As often happens with lists of alleged regional peculiarities, their opposites can be readily cited. Maps of southern states are more liberally sprinkled with classical place names than with Slabtowns and Smackovers—Athens, Sparta, Corinth, Carthage, Memphis, and Rome, for example. Personal names often reflect the same taste. Every southerner knows an Augustus, a Lucius, a Virginius, or perhaps even a Dionysius or a Cleanth. Where but from a southern state could emerge in different centuries an ambassador and a prize fighter both named Cassius Marcellus Clay? Names are also given to commemorate heroes, as witness the frequency with which one finds in phone books of southern towns the initials G.W. and T.J. for the first and third presidents of the republic. Given names very often serve to perpetuate the family name of a mother or some worthy forebear. Drawing illustrations from modern southern writers alone, one thinks of such given names as DuBose, Carson, Erskine, Flannery, Truman, Penn, Stark, and Walker.

More frequently than names, southern speech and accent draw comment from non-southerners and serve as popular stereotypes of regional distinctiveness. Linguists agree that there are speech differences, but agree on little else about them. They write more on the speech of the South than on that of any other region. Popular misconceptions abound. While most Americans, southerners as well as northerners, perceive southern speech as different, specialists cannot identify anything that can be termed a “southern accent” or a “southern dialect.” There is more diversity of speech in the South than in any other region and no more uniformity than exists in the nation as a whole. Nothing in the way of a slower speech tempo justifies the folk perception of “southern drawl.” That has more to do with rhythm, cadence, and intonation, as do differences between the way blacks and whites speak. Blacks and upper-class whites share r-lessness, and all classes may slip into you all, use ma’am and sir as modes of address, substitute liked to for almost, and diphthongize vowels in time and tide. But one quickly runs into diversities such as the lower South stretching vowels in bid, bed, and bad, and the upper South pronouncing steel like stale, and stale like stile.

Any number of theories are advanced to account for these mysteries, some of which, such as climate and life style, are manifestly absurd. There is full agreement upon no one theory. Contrary to widespread impression no evidence exists that southern English is losing its distinctiveness. It has undergone major changes, as have all varieties of English in the last half-century, but it is not being homogenized or “standardized” by television addiction or northern migrants. To the contrary is evidence that southern youths are consciously resisting change more than their elders and would not be caught speaking “like a Yankee.” A southern university that offered a course in correcting southern accents was greeted by student outrage and harassment of the instructor. Speech so regarded becomes an assertion of identity, loyalties, and roots, and cultural departures from the “norm” a matter of conscious choice as well as heritage.

Freud’s phrase, “the narcissism of small differences,” may occur to skeptics as the appropriate label under which to file away such data. The differences are indeed relatively small compared with those encountered in a few miles of travel across Europe and other parts, even within a single nation’s boundaries. The mention of Basques, Scots, Armenians, and Kurds in connection with southern insistence upon cultural difference can evoke smiles. Nevertheless differences do exist. Some of them have been around for a long time and are of genuine significance. A few are self-serving and self-perpetuating. Any scholarly enterprise seeking to justify separate regional study of any aspect of life in the South must assume some regional distinctiveness and may occasionally exaggerate small differences. We already have a large encyclopedia of southern history and an encyclopedia of southern religion and one on black life.1 And now we have an encyclopedia on the region’s culture.

Advertisement

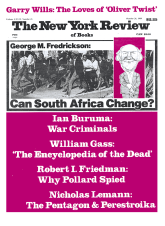

Exceeding the size of the others, The Encyclopedia of Southern Culture suggests more the dimensions of the unabridged Webster’s International. It runs over 1,600 pages set in wide double columns, pages of a size that contain at least three times the number of words in an ordinary book page. Of the 164 definitions of culture that anthropologists have catalogued, the editors take as their “working definition” the broad one of T.S. Eliot—“all the characteristic activities and interests of a people.” This means not only creative achievements in music, literature, art, and architecture, but the whole “cultural landscape,” including “everything that has sustained either the reality or the illusion of regional distinctiveness.” The editorial policies are inspired by Eliot’s belief that “culture is not merely the sum of several activities, but a way of life.”

The Encyclopedia is sponsored by the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, where the editors, Charles Reagan Wilson and William Ferris, are located. It is an achievement that does credit to both the university and the editors. The editors have secured contributions from some eight hundred specialists, most of them in the South but many from elsewhere. With few exceptions, they appear to take their assignments seriously and give us their best. To put one question at rest right off, any suspicion of special pleading, romanticizing, or provincial defensiveness may be put aside. “Benighted South” gets more than equal time with “Sunny South”—all the way from Garrison’s “great Sodom” through the southern literature of depravity, idiocy, bigotry, incest, rape, lynching, murder, and suicide down to modern South bashers. The Snopeses lived there too, and they had their culture.

So did the blacks, and to anticipate a second question, they are also included. In fact it may seem to some that what with a foreword by that inventive genealogist, Alex Haley, and the bracketing of Alice Walker with William Faulkner, the editors may have leaned over backward in this respect. They do perceive clearly, however, that while slavery and segregation, among other things, forced it into distinctive patterns, black culture is very southern—and that all southern culture is part black. W.E.B. DuBois has an eloquent and often quoted passage about the “two-ness” of being both black and American. An unexplored implication of the work under review is a third dimension added to the “two-ness”—that of being southern as well. White southerners also share the “three-ness” by virtue of the biracial component of their culture. Cajuns, Jews, and Creoles have still another, but the southern component bulks large for all. Jews with a southern accent constitute some of the oldest families of Charleston and Savannah.

Myth, symbol, and image—carefully so labeled—receive due attention. The South at times seemed “a land populated by a succession of predictable stock characters,” and stereotypes: belles, cavaliers, darkies, Klansmen, sadistic sheriffs, demagogic politicians and preachers, and nubile cheerleaders. To a remarkable extent the symbols are of northern origin, including “Dixie,” the Confederacy’s favorite song and popular name. A Connecticut Yankee produced a novel crowded with durable southern stereotypes in Uncle Tom’s Cabin; an Ohioan produced Cotton Is King; Pennsylvanian Stephen Foster composed most of the classic “southern” songs, from “My Old Kentucky Home” to “Old Black Joe”; New Yorker James K. Paulding, a fire-eating Yankee secessionist, helped to create the plantation legend in his fiction; Currier of Massachusetts and Ives of New York gave us the sentimental lithographs of southern life. Needless to say, southerners themselves contributed their share of stereotypes.

Substance and reality behind image and legend are not neglected. Back of the rich mythology of southern violence lies plenty of hard fact. For the last century such statistics as are available place the states of the South ahead of the rest in criminal homicide, usually very far ahead. This is true of whites and blacks, with black homicide rates several times those of whites, but with suicide rates for both races (as well as rates of mental illness, heart diseases, and alcoholism) appreciably below national averages. The raw facts are reflected in popular attitudes: those toward capital punishment, for example, with the South accounting for a little less than a third of the nation’s population but 65 percent of its 1,202 prisoners awaiting execution in 1983. Or the region’s notorious gun culture, with ownership of firearms (though not of handguns) greatly exceeding rates elsewhere. Homicide in the South is personal rather than random, typically the result of argument and disputes rather than the accompaniment of another “crime in the streets.”

Advertisement

It was in such a society that the code of honor and the duel could flourish, and along with that the mountain feuds, mob violence, race riots, night riders, political shoot-outs, labor wars, Texas Rangers, Ku Kluxers, the James brothers, the Hat-fields and McCoys, and in the late 1930s “Bonnie and Clyde.” Southerners enshrined a great variety of “social bandits” and outlaw heroes in myth and legend, all the way from the Regulators of colonial South Carolina to the “Dukes of Hazard” of the recent television series. In 1958 more than 10,000 Mississippians attended the funeral of Kennie Wagner, a jail-breaking, gunslinging outlaw hero and survivor of many shoot-outs. Whites had the Klansmen and the James brothers, blacks their Harriet Tubman and John Brown. Folk song and story are heavily burdened with subjects and themes of violence and outlawry, and no less so southern letters, including the best.

Theoretical attempts to explain the distinctiveness of the South’s culture receive little attention in the Encyclopedia. An exception is made of the “Celtic” theory of Grady McWhiney and Forrest McDonald, which has special bearing on the theme of violence. These writers stress the predominance of the Celtic population of the South, people of Scottish, Irish, Scotch-Irish, Welsh, and Cornish origins. By the end of the antebellum period, they contend, the South’s white population was three quarters or more Celtic, as compared with about the same proportion of English people in New England and the upper Middle West. The Celts are said to be characterized by distaste for hard work, love of leisure, rural values, and a reckless indulgence in drink, hospitality, and outdoor sports, along with a tendency to lawlessness and violence in the settlement of disputes, especially those over matters of honor. This theory applies to some southern characteristics—for example the martial tradition and battle behavior—more readily than to others. Much the same might be said of a theory offered elsewhere by the present writer, a theory that relies rather heavily on the South’s un-American encounter with history, with defeat, failure, and poverty, to explain its distinctiveness.

But no theory yet advanced adequately explains what is one of the South’s most striking departures from the national norm—contentment. By huge margins white and black southerners polled over the last fifty years have liked it better where they are than any other Americans, 60 percent as against 43 percent, and 70 percent of North Carolinians at one extreme to 29 percent in New York state at the other. They are persuaded, for reasons best known to themselves, that they live in the best community of the best state in the country. 2 The statistic tells much about the pace of politics and the aversion to radical change in the region.3

If contentment is somewhat difficult to reconcile with violence, it is even harder to pair up with restlessness and mobility. One thinks first of the millions of migrants who have moved north since World War II. Again and again we have been assured by southern writers we respect that people of the South are profoundly attached to place and community. Yet we now learn that of the top ten states in number of mobile homes purchased in 1984, eight were southern. The first one on the list that is not southern is the huge state of California, and it was near the bottom. Evidently the 40,000 Okies and Arkies of the 1930s were not the last southerners prepared to pick up and go. In fact another symbol of mobility is the pickup truck, which has grown in popularity until “about half the new vehicles sold in the South are pickups.” More than a mobility symbol, it is something of a status symbol for many, and “a ‘good old boy’ without a pickup is like a cowboy without a horse.” In the meantime the horse and mule population of the country peaked at 26 million in 1920 and declined to less than 4 million in 1958—most of them concentrated in the South.

The fervent religiosity of the region and its defiance of the secularist and the “modern mind” have long been noted as distinctive traits. According to encyclopedic authority, “The South is the only society in Christendom where the evangelical family of Christians is dominant.” The various evangelical denominations differ somewhat in style and teaching but share “four common convictions”: the final authority of the Bible in all matters of belief and practice, the direct access of all and sundry to the divine spirit, traditional morality in personal behavior, and worship in informal styles.

Informality and self-expression took on colorful forms in white Pentecostal and Holiness sects and in black churches of various denominations—“let’s really sing, all together now”—but commonalities among the evangelical family are striking. To people of poverty an expressive, emotional, cathartic religion had special appeal. Lutherans and Episcopalians as well as Mennonites and Quakers have remained marginal to the dominant evangelicals. Living and writing in this religious atmosphere, the isolated Roman Catholic Flannery O’Connor called her native region “Christ-haunted.” Those whose imagination fed on the South could not avoid the powerful religious presence. “I grew up with that,” said William Faulkner, “took that in without knowing it. It’s just there. It has nothing to do with how much of it I might believe or disbelieve—it’s just there.” And to be “there” was to be ingrained in the corpus of his writings.

Southerners figured disproportionately in the audience of the “electronic church”; and virtually all of the major “televangelists”—Billy Graham, Oral Roberts, Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, Jim Bakker, Jimmy Swaggart—are southerners whose headquarters and enterprises are mainly in the south, which is the scene of their more sensational indiscretions and tearful confessions. By the early 1980s the number of syndicated religious programs (those broadcast on five or more TV stations had grown to nearly one hundred, and the total revenues from religious broadcasting in the country to an estimated billion dollars. By the mid-1980s the value of the Oral Roberts empire alone approached that amount. Televangelists transcended denominational boundaries but did not alter them. In the Deep South states of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia the combined Baptist and Methodist church memberships alone constituted 87 to 88 percent of church members. And among black church members the proportion accounted for by the same two denominations was even larger.

While black culture is deeply southern, it probably has in some respects as much distinctiveness from that of the white South as the culture of the South has from that of the North. The Encyclopedia editors cope with this by combining segregation with integration—giving the subject a separate section and also integrating it into other sections. This solution comes at the cost of some duplication and awkwardness, but is the consequence of genuine needs. The development of black business is described as “a bittersweet synthesis of two mainstays in American culture—capitalism and racism.” Jim Crow segregated the market and customers for black capitalists. Segregation also proved the mainstay and furnished the isolated clientele for black doctors, dentists, lawyers, preachers, journalists, and other professionals who hung out their shingles along “Negro Mainstreets” of southern cities, such as Beale Street in Memphis, Auburn Avenue in Atlanta, and what was once known as the “Black Wall Street of America,” the city of Durham, North Carolina. The new black middle class came out of all-black segregated colleges, churches, and communities. And from the same seats of segregation came the leaders of the mighty upheaval that destroyed segregation with the civil rights movement.

Charles Joyner is right in saying that Africans came to America without a common language or culture, but would seem to be going a bit far in holding that “enslaved Africans were compelled to create a new language, a new religion, indeed a new culture.” What I think he intended to say is that they Africanized the old culture they encountered in the South or adapted it to their needs. Perhaps this is what he means by their “creolization of black culture.” None of this is to deny the many creative contributions Africans made to the culture of the South and to the world of art, literature, and music. If there is any product of southern culture that has gained worldwide recognition and appreciation, it is jazz. And, of course, it “has proved enormously influential on white southern musicians.” Elvis Presley may well be “the most famous southerner of the 20th century,” but “indelibly southern” as he is, his style and his frantic performances are hardly conceivable without a background of W.C. Handy, Jelly Roll Morton, and Leadbelly Ledbetter.

The Encyclopedia contributor who introduces the section on the more formal arts in the South is on the right track in pointing out that there is more to be gained “by examining and objectively describing what exists than by trying to categorize what is or is not uniquely southern.” But even the reasonably well informed on architecture might need help in identifying such traditional domestic architectural styles as the saddlebag and the dogtrot houses, or the shotgun, the T-house, or the double-pen-plan styles—more than they would in identifying split-level ranch-house styles. There is good reason for a separate section on “Porches” defined as “the public/private space across the front of a building,” a functional living space until air conditioning arrived. Porch styles, whether two stories graced with Doric columns or simple roof extensions supported by poles, announced the social status of the occupants or that of the customers and patrons desired when used by banks or motels.

Although the Kentuckian D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915) and David O. Selznick’s Gone With the Wind (1939) are archetypal southern classics (the latter was voted the all-time favorite of moviegoers), the “southern” movie as a distinctive genre has never flourished as famously as the “western.” The southern movie has, however, had its moments beyond the two works cited. It has been particularly successful in adapting to film use literary works of southern writers, for example the plays of Tennessee Williams and Lillian Hellman and, often in watered-down forms, the novels of William Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren, and Erskine Caldwell, some of whose works have been also adapted to television use. In frequency of appearance on network television series at the soap-opera level, the South has no rival except the Old West. It is completely without rivals in the country-music industry (including all genres from Bluegrass and Blues to Tex-Mex and Zydeco) as a source of raw materials, styles, performers, and creative talents for the country as a whole.

Any South-watcher who half tries to keep posted will confirm the recent occurrence of what can be described as a culture explosion in the creative arts, or at least in the patronage and attention given them. And all this in what Henry L. Mencken used to call “The Sahara of the Bozarts,” without rival for barrenness short of Asia Minor. At Chattanooga, for example, southerners turn out by the thousands to attend three days of a writers’ conference, and to Nashville flock scores of thousands for a four-day book fair. Working artists of the region are now numbered in the thousands and their supporters in the millions. Every city of any size has its museum, its art galleries and dealers. Including museums of all types, the South accounts for some 1,500, or a quarter of those in the nation. A comparable development has occurred in theaters and playhouses, some of them built to house also symphony, ballet, and repertory drama. Every spring at Charleston, South Carolina, the Spoleto Festival provides a showcase for the fine arts and links European cultural traditions with those of the South. It would seem enough to give South-bashers pause for a bit.

Other changes, some of them vast and destructive, continue to sweep and alter the cultural landscape of the South beyond recognition. Saddlebag houses, camp-meeting grounds, cotton-gin towns, bighouses, cropper cabins, and plantations—all stand deserted or in ruins. Cities, even small ones, suddenly take on soaring skylines on the order of Atlanta and Houston, while thousands of old villages and small towns undergo lingering deaths or vanish from the map, and nuclear plants, astronautical enterprises, and Japanese industries take their places. The South is not a region new to change. It grew at twice the nation’s growth rate between 1970 and 1980. Its birth rate has long exceeded the national rate. Its population almost doubled between 1940 and 1980 and increased more than forty-fold since the first census two hundred years ago. In 1950 over half of all southerners lived in rural areas; now a smaller proportion than that of the country as a whole are rural dwellers. Change and contrast. The two poorest states in the Union are Mississippi and Arkansas and the only two states that rise to the national average of per capita income are Florida and Virginia.

The long season of change that has swept away so much of the old and traditional and distinctive and brought in as much that is new and modern and standard American has been assumed to have leveled the “small differences” of regional distinctiveness. If that is assumed to be true, little justification for the Encyclopedia would remain, save as it relates to a bygone past. But to make that assumption would be to disregard impressive evidence to the contrary and persistent—some would have it perverse—adherence among southerners to “a strong sense of themselves as different from other Americans.” While southerners no doubt exaggerate their differences from other white Americans, the differences are by no means negligible. Elaborate opinion polls on cultural questions reveal them to be larger than those between Catholics and Protestants, males and females, manual and other types of workers, rural and urban people, and about at the same level as differences between blacks and whites. Whites identify themselves with the South more than Catholics with their religion, more than union members with other unionists, and at about the same levels as blacks and Jews with other members of their race.4 Regional distinctiveness would sometimes seem expanded to compensate for the Lost Cause of southern independence.

After the Civil War many thousands fled the South to become fugitives, exiles, or expatriates abroad. They scattered to England, France, and Canada, to Egypt, Japan, and Australia. Some five or six thousand Confederates emigrated to Central America and Mexico, and three or four thousand to South America. Most of the emigrants returned to the United States in the 1870s, but some four hundred descendants still survive in the Brazilian colonies with recognizable southern accents, dialects, tastes, Confederate flag decals, and preferences for cornbread, pecan pie, and watermelon. Far more emigrants settled in the North and continued to do so through the following century. They have figured in literature from Henry James’s Basil Ransom in The Bostonians to Thomas Wolfe’s uprooted Ishmael, and characters of Harlem Renaissance novels. Whether or not the leading student of the exiles is right in saying that they “remained southern in mind and heart,” they have remained for the most part a self-conscious group, seeking each other out for company and sympathy or support. Very few of them deny or conceal their regional origins.

For southern writers, scholars, artists, and intellectuals the exile experience in Yankeedom, whether temporary or permanent, has become a part of their maturing. For one thing it has compelled them to think more about being southern, and often that has helped in healing the alienation that originally sent them into exile. More of them return as repatriates now that opportunities for them have improved. But for several generations the South suffered much cultural impoverishment through a drain of talent, ability, imagination, and creativity. A half-century ago more than a third of those in Who’s Who in America listed as born in the South were living in other sections of the country, and the percentage increased before it started to decline.

Encyclopedias are normally used as reference books, to “look something up.” For the Britannica (at least for the good old eleventh edition) a command of the alphabet is practically all that is required. Not so with the encylopedia at hand, for the use of which no little ingenuity is demanded. The editors deserve some patience and sympathy, for they have been given, or have given themselves, an unusual task. To start with, they bite off a lot to chew by taking on Eliot’s definition of culture—“all the characteristic activities and interests of a people,” and “not merely the sum of several activities, but a way of life.”

That difficulty is compounded by the existence of not one but a cluster of subregions, each with a distinctive cultural style and by more than one way of life—the biracial aspect, for example. Then the editors had to take account of two encyclopedias of the South, one on history and religion already in print, plus two substantial reference works on literature and writers. The editorial solution is to organize all entries alphabetically under twenty-four sections, also alphabetically ordered from Art, Architecture, and Black Life to Urbanization, Violence, and Women’s Life. The trick is to guess in which section to find a particular entry. Is a black woman poet, for example, to be found under Black Life, Literature, or Women’s Life? Audubon is described as “the most famous of all painters of natural history,” yet he does not turn up under Art, but in the section entitled Environment—along with Winslow Homer, Catfish, Collard Greens, and Kudzu. A handy index would help, but this one comes at the heavy end of 1,600 pages and is not always as helpful as it might be.

With such a huge variety of subjects to treat and interests and people to accommodate, the work is bound to meet with a variety of assessments. Social historians and folklorists, for example, will presumably find the abundance of folksy subjects and the occasional lapse into a folksy tone more welcome than will others. Few will be entirely pleased to discover that in the section on History and Manners, items on Fried Chicken, Gays, Goo Goo Clusters, and Grits followed alphabetically by items of comparable length on Stonewall Jackson, Thomas Jefferson, Robert E. Lee, and James Madison, followed in turn by disquisitions on Mint Juleps, Moon Pies, and Moonshine. Any critic of experience and charity will take for granted the presence of typos and errors. There are some here, but for a work of this size they are comparatively few. The entry on Joanne Woodward, however, can be found only with difficulty—the index gives the wrong pages.

It should be emphasized that such lapses are not characteristic of the book, in which much care is manifest. It contains learned and provocative articles and unexpected rewards. It is a pity that since the Encyclopedia will be used for reference rather than for reading, the user will miss the many rewards incidental upon a reviewer’s obligation to read and browse extensively. Two essays will illustrate these possibilities, one headed “Stoicism,” the other “Fatalism,” separated by more than six hundred pages. The first is found in the section called History and Manners and the second in one called Religion, but they are essentially about the same thing. The one entitled Stoicism is by one of the coeditors, Charles Reagan Wilson, who contributes a number of articles of his own.

Wilson traces stoicism as a theme running through southern thought from the Enlightenment and Jefferson’s writings down to the present day. Both he and Robert L. Johnson in his treatment of Fatalism cite writings of Faulkner, O’Connor, and Walker Percy as examples. According to Percy the South was always more stoic than Christian, and in whatever degree the virtue of nobility and graciousness may have existed in the region it was “the nobility and graciousness of the Old Stoa.” Others suggest that stoicism enabled southerners to be both Cavaliers and Puritans and to combine outward grace and inner sternness. Wilson sees the Civil War as “a crucial stage in the development of stoicism in the South” and Robert E. Lee as exemplar of postwar stoicism in defeat and “the supreme example of the South’s attempt to balance Stoic and Christian virtues.”

The linking of stoicism and religion reminds us that the cult of honor is often mentioned here and elsewhere as a component of the South’s prevailing ethical system and a feature of its stoicism. Edward L. Ayers has a thoughtful piece on honor tucked away under the section on Violence and limited to less than a page. But it would have been interesting to hear from Bertram Wyatt-Brown, the leading authority on the history and anthropology of southern honor. He seriously challenges the reconciliations of the code of honor with evangelical religion and the South’s claim of doing so. He contends in a seminal article recently published that “the southern mind has always been divided between pride and piety” and that “the dynamics of honor and religion” have never been securely or congenially reconciled for long. He concedes that the romantic élan of the Confederate cavalier produced heroes who were “both Christian gentlemen and men of honor.” But he is persuaded that “neither honor nor evangelism wholly triumphed” and that “the South would have to live thereafter with a divided soul.” This dichotomy, in his view, “recognized no need to make choices between honor and Christianity, between Athens and Jerusalem. The white southerner’s deity could be worshiped not only as a saving Christ but as the Ruler of Honor, Pride, and Race.” 5

To extend the discussion in this manner is to suggest the continued liveliness of interest in the South and its seeming inexhaustibility as a field of study. It might also furnish further proof of the value of the Encyclopedia as a scholarly undertaking as well as suggesting future needs for revision or supplement to keep up with ongoing scholarship.

This Issue

October 26, 1989

-

1

David C. Roller and Robert W. Twyman, eds., Encyclopedia of Southern History (Louisiana State University Press, 1979); Samuel S. Hill, ed., Encyclopedia of Religion in the South (Mercer University Press, 1984); W. Augustus Low and Virgil Clift, eds., The Encyclopedia of Black America (McGraw Hill, 1981).

↩ -

2

John Shelton Reed, One South (Louisiana State University Press, 1982), pp. 154-155.

↩ -

3

Earl Black and Merle Black, Politics and Society in the South (Harvard University Press, 1987), pp. 229-231.

↩ -

4

John Shelton Reed, “Southerners,” in Stephan Thernstrom et al., eds., Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (Harvard University Press, 1980), pp, 944-948; Reed, One South, pp. 21-23.

↩ -

5

Bertram Wyatt-Brown, “God and Honor in the Old South,” in Southern Review (Spring, 1989), pp. 283, 295-296; see also his Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South (Oxford University Press, 1982).

↩