Bill McKibben lives in the Adirondack Mountains, of New York State, in an isolated house some twelve miles from the nearest town. He works as a writer and spends much of his leisure time hiking in the surrounding woods. He regularly attends a Methodist church because he likes the fellowship, loves to sing hymns, and finds meaning in the Old and New Testaments. But he finds the presence of God mostly in the outdoors. He says that, like many people in the modern era, he has been troubled by a crisis of religious belief and that he has “overcome it to a greater or a lesser degree by locating God in nature,” declaring,

Most of the glimpses of immortality, design, and benevolence that I see come from the natural world—from the seasons, from the beauty, from the intermeshed fabric of decay and life, and so on.

For McKibben, nature proclaims eternity, an intricate harmony made particularly appealing by its permanence—“the sense that we are part of something with roots stretching back nearly forever, and branches reaching forward just as far.”

The End of Nature expresses a sensibility resembling that of the natural theologians of the nineteenth century, who searched assiduously for evidence of God in nature’s particulars. But the resemblance is superficial. McKibben is not a theologian, and, while he sees the earth as “a museum of divine intent,” he is not interested in its phenomena as keys to revelation or in its intricacies—how, for example, beetles live or mountains form—as specific evidence of design. What absorbs him is not so much the facts of nature as the idea of it, the idea of a nature that is raw, wild, untainted by man. To McKibben’s mind, we need unspoiled nature in its rounded seasons—“so that we can worry about our human affairs secure in our knowledge of the eternal inhuman.”

McKibben’s book ranges over features of nature around the world, but his sensibility is especially American, drawing from the powerful Edenic theme in American culture, from the American perception of the continent’s unspoiled natural environment as a garden of innocence. As he comments on a nineteenth-century traveler’s description of a lovely valley in the region of the Missouri River:

If this passage had a little number at the start of each sentence, it could be Genesis; it sticks in my mind as a baseline, a reminder of where we began.

Like Nathaniel Hawthorne, who bridled when, at ease in a forest clearing, he heard the blast of a distant train whistle, McKibben resents the intrusions into nature of human technologies and their ravages. The quiet of the wilderness behind his house is daily broken by the screech of air force jets flying sub-radar practice runs. But while pesticides taint the water table, acid rain injures the trees and pollutes the lakes, and the Chernobyl accident irradiated vegetables in Europe, he believes that such abominations can be halted and nature returned to normal. He has observed that the air force jets return to base, that “most of the day, the sky above my mountain is simply sky, not ‘airspace.”‘ He writes,

We never thought that we had wrecked nature. Deep down, we never really thought we could: it was too big and too old; its forces—the wind, the rain, the sun—were too strong, too elemental.

But he now believes that we have wrecked it. The End of Nature is an attempt to explain how and why. The book travels both inward, through personal reflections, and outward, seeking to identify a crisis that is not only public but spiritual. It is part popular science and part poetry, a sensitive and provocative essay of alarm, a kind of song for the wild, a lament for its loss, and a plea for its restoration.

By the “end of nature,” McKibben does not mean the end of the world. He means the end of “a certain set of human ideas about the world and our place in it,” a demise begun by “concrete changes in the reality around us—changes that scientists can measure and enumerate.” Among the disturbing changes is the depletion of the ozone gas that normally forms a protective layer high in the earth’s atmosphere. Ozone is a molecule of oxygen made up of three oxygen atoms. Its depletion was first recognized in 1985 when a gaping hole was discovered in the ozone layer over Antarctica. The catalyst of the depletion was the release into the atmosphere of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), a family of man-made chemical compounds that can perform various services, notably making spray cans spray and air conditioners cool. Ozone molecules are much less abundant than the type of oxygen essential for the breathing of living organisms, but they play an important part in the biosystem: they prevent much of the sun’s ultraviolet radiation, which can be highly injurious to life, from penetrating to the earth’s surface.

Advertisement

One of the scientists who discovered the relationship between CFCs and ozone depletion is Sherwood F. Rowland of the University of California at Irvine. McKibben reports that, during the course of his work, Rowland came home one night and told his wife, “The work is going very well, but it looks like the end of the world.” For McKibben, what has truly, and more profoundly than anything else, brought about the end of the natural world is the greenhouse effect.

An ordinary greenhouse becomes warmer than the air outside it by trapping radiation from the sun. The sun’s rays, having entered through the roof glass, are partly reflected back up to the glass, which in turn reflects some of them back into the greenhouse space. In 1896, Svante Arrhenius, the eminent Swedish physical chemist, pointed out in a brilliant article, “On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature on the Ground,” that the earth and its atmosphere form a natural greenhouse.1 Carbonic acid consists of—and in the atmosphere dissociates into—water and carbon dioxide (CO2). The carbon dioxide comes from the joining of carbon and oxygen, one of the most common chemical processes on the earth. It occurs in the burning of carbon-abundant organic matter, including forests ignited by lightning or coal and oil fired by man.

Carbon dioxide is a trace chemical in the air, only a few hundred parts in every million air molecules, yet even that small amount acts like the glass in a greenhouse, trapping some of the solar radiation that constantly bathes the earth. Without the greenhouse trapping, the reflected radiation would escape into outer space, and the earth would be some sixty degrees cooler on the average than it is. But we can have too much of a good thing. Arrhenius, who wrote his article primarily to account for the type of climatic swings that had produced the ebb and flow of glaciers, calculated that a tripling of the amount of CO2 from then-current levels would raise Arctic temperatures as much as sixteen degrees Fahrenheit.

Although industrial growth has stimulated a steady increase in the burning of fossil fuels—and, as a result, a steady increase in the amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere—CO2 concentrations have increased no more than 25 percent since Arrhenius’s day. The oceans soak up carbon dioxide, and so do plants and trees. However, the ocean does not have an infinite capacity for absorbing CO2, and even though trees and shrubby forests still cover some 40 percent of the earth, deforestation has been taking place at an accelerating rate. For example, McKibben points out that, in the century before 1975, the Brazilian state of Para lost 18,000 square kilometers of forest and in the decade after 1975 ten times as much. Almost half the rise in atmospheric CO2 since the beginning of the industrial era has occurred in the last thirty years. Moreover, other trace atmospheric gases that have also been pouring into the atmosphere—notably the CFCs and methane—intensify the CO2-induced greenhouse effect by between 50 and 150 percent.

Human beings have produced the CFCs, and human beings are at least partly responsible, if indirectly, for the methane increase, even though the gas is generated by a variety of natural processes—for example, the breakdown of organic matter by bacteria in such locales as rice paddies and the guts of cows and termites. It can be argued that people, by killing trees, have made more dead wood for termites to feed on. Certainly they have raised more and more cows and rice to nourish the rapidly growing human population.

The climatic impact of CO2 was a relatively obscure public issue as late as the mid-1970s. The attention currently being given to it owes much to the weather of the 1980s. According to a British study, the decade was already the warmest on record when the brutally hot spring and summer of 1988 came along, blistering streets in US cities, bringing drought and crop disasters to many farms, and feeding a seemingly endless fire in Yellowstone National Park. Suddenly, the greenhouse effect commanded alarmed consideration on the front pages, the broadcast networks, at celebrity benefits, and in the United States Congress, where, at a hearing on the subject in June 1988, Senator J. Bennett Johnston of Louisiana publicly worried about the 101-degree temperatures in the capital and the ruin of soybean, corn, and cotton crops. In testimony at the hearing, the respected climatologist James Hansen declared that the warming of recent years was 99 percent likely to have been a greenhouse result. He said, “It’s time to stop waffling so much. It’s time to say the earth is getting warmer.”

Advertisement

Stephen Schneider, who is head of Interdisciplinary Climate Systems at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado, as well as a prominent climatologist, had been laboring for some years to draw attention to the greenhouse effect. He notes that

in 1988, nature did more for the notoriety of global warming in fifteen weeks than any of us or the sympathetic journalists and politicians were able to do in the previous fifteen years.

The provenance of that notoriety worries scientists like Schneider. The heat of the 1988 summer could have been a random event, a local statistical variation on a steady climate. It is scientifically indefensible to take it as hard evidence that the greenhouse effect has become an urgent reality. Even Hansen hedged about the significance of 1988, declaring that one year’s weather was not indicative of a climatological trend (while adding that the greenhouse effect “increases the likelihood of such events”). Scientific integrity aside, if a few relentlessly hot years stimulate public alarm about global warming, a few benignly cool ones might well dissolve the alarm into indifference. The press is fickle, and the kind of attention now paid the issue by people such as Bonnie Reiss, an enterprising activist and entertainment lawyer in Los Angeles, might give an environmental scientist the shivers. While at a global warming conference, Reiss had what she calls “this great awareness…like ‘Field of Dreams.’ If you do this it will happen.” So she did it, rising to say of the onrushing global hazards, “Wouldn’t one mention of any of this on ‘The Cosby Show’ do more than all your scientific books combined?”2

Schneider’s Global Warming is an attempt to instruct the public directly about the state of current knowledge of the greenhouse effect. His treatment is workmanlike, enlivened largely by the energy of his involvement in the subject. He is convinced that an informed citizenry is essential to forestall “nondemocratic choices made by an elite group of experts.” His book serves as a detailed scientific companion to McKibben’s more poetic work—indeed, McKibben draws on the writings of Schneider as well as those of other climatologists. Global Warming is lucid enough to clarify many matters for laypeople and, one would think, evenhanded enough to satisfy most scientists.

Schneider reveals that the greenhouse effect is a “complex, uncertainty-riddled topic.” Currently there is broad scientific consensus that the greenhouse effect is a realistic hypothesis; and that the earth’s average temperature has in fact risen by about one degree Fahrenheit during the last century. However, there is considerable debate about how much of this warming is attributable to the increase in atmospheric CO2 and other trace gases; and about whether that increase has already set the greenhouse effect in motion and, if it has, or when it does, what the consequences will be for global weather.

Analyses and predictions of climatic movements depend upon empirical studies of past trends and computerized mathematical modeling of the physical and biological systems—land, air, waters, ice and snow, and living organisms—that, acting together, yield the terrestrial weather. Both methods suffer from difficulties, notably the unreliability of weather data extending back a century or more and the complexity of interactions among the key physical systems. Mathematical models are essential to predictions of climatic behavior in a world in which the greenhouse effect has become more intense—a world without useful precedent for human society. It thus gives one pause to learn from Schneider that the models fall somewhat short when applied to the climate of the past. They show that a warming of some two degrees Fahrenheit—not just one degree—should have occurred in the last century.

All the same, as scientists say, “the sign is right”; that is, the models and the empirical evidence agree on the general direction of temperature change, toward warming. To Schneider, the result means that the models of the sensitivity of the climate to greenhouse gases are probably accurate “within a factor of two to three” and that they can thus predict likely greenhouse climates of the future within a similar range. Schneider himself holds that “we are already a decade or two into the greenhouse century” and that by the year 2000 it will be evident that the 1980s were the period when “the global warming signal emerged from the natural background of climatic noise.” McKibben, more cautious about whether the signal has been seen to emerge, declares that to doubt that the warming will happen because it has not yet appeared “is like arguing that a woman hasn’t yet given birth and therefore isn’t pregnant.”

Many scientists appear to agree that the earth is already heavily expectant with CO2-induced climatological change; that it will become more so as the world burns still more fossil fuels; that when the level of CO2 and equivalent trace gases doubles from preindustrial concentrations—which will happen some time during the next century, at current emission rates—the average global temperature will rise three to eight degrees Fahrenheit; and that this rise will yield a climatological shift of drastic proportions.

The shift is likely to produce miscellaneous effects that are “literally infinite,” writes McKibben, who is excellent at specifying the tangible personal consequences of theories, abstractions, and numbers.3 The most commonly discussed effect of global warming is the partial melting of the polar ice caps, which would create a rise in the global sea level of one meter or more (severalfold more, in some estimates). Billions of dollars of coastland, it is estimated, would be inundated. Storms would flood settlements on flat coastal plains. Both people and wildlife would be driven inland. The salty oceans would surge upstream through the mouths of rivers. The warming would intensify the evaporation of water basins, reservoirs, and rivers, reducing freshwater supplies everywhere, but more in relatively drier regions—for example, the western United States. McKibben reports that if a temperature increase of two degrees centigrade were to occur, “the virgin flow of the Colorado would fall by nearly a third.” However, the prospects for wetter areas—say, greater New York City—are not happy either. The government says that “doubled carbon dioxide could produce a shortfall equal to twenty-eight to forty-two percent of planned supply in the Hudson River Basin.”

McKibben notes that some journalists, commenting on the larger vegetables and agricultural yields that may result from the photosynthesis of more abundant CO2, have found “green linings to the cloud of greenhouse gases.” Yet the negative consequences of more CO2 appear dramatically to outweigh any positive ones. A warmer climate, with lower rainfall, would turn arable croplands into dry grassland or even into desert. It would devastate the woods where McKibben lives—“the trees will die,” he exclaims—fostering the growth of shrubs and driving northward to cooler regions the pines, yellow birch, blue spruce, swamp maple, maple, and hemlock. Animals would try to migrate to more suitable ecological niches, but they would be blocked by highways and fences. In the summer, people would swelter in cities five to seven degrees warmer—and warmer for more days—than they are now. “Science,” McKibben remarks,

has yet to devise a way of measuring what percentage of people feel like human beings on any given August afternoon, or counting the number of work hours lost to the third cold bath of the day—or, for that matter, reckoning the lost wit and civility in a population concerned mainly with keeping its shirts dry.

However, for McKibben, the worst consequence of the greenhouse effect is that “the idea of nature will not survive the new global pollution—the carbon dioxide and the CFCs and the like.” He argues,

We have changed the atmosphere, and thus we are changing the weather. By changing the weather, we make every spot on earth man-made and artificial.

There will be nothing natural about the spring rain, the winter snows, or the July heat wave; nothing natural about the seasons—nothing inhuman about nature. On the contrary, nature will be crowded with human presence: the metaphoric noise of the chemical chain saw—the taint of CO2, CFCs, and acid rain—will always be in the woods, drowning out the voice of God. “We live,” McKibben writes,

all of a sudden, in an Astroturf world, and though an Astroturf world may have a God, he can’t speak through the grass, or even be silent through it and let us hear.

Nature has become “a category like the defense budget or the minimum wage, a problem we must work out” instead of “a category like God—something beyond our control.” Here is McKibben’s main lament:

We have deprived nature of its independence, and that is fatal to its meaning. Nature’s independence is its meaning; without it there is nothing but us.

McKibben anticipates the objections to his arguments, and he tries to answer them. The laws of physics and chemistry remain in force: Are not natural processes still the master? Man is part of nature: How can his activities bring it to an end? These, McKibben contends, are “semantic points.” The nature that we ordinarily apprehend is not the whirling electrons of the scientist but the tangible experience of leaves turning colors and rain falling. It makes no difference that we are natural entities, for “we have ended the thing that has, at least in modern times, defined nature for us—its separation from human society.” He adds that what we have done grips us with sadness, a sense of loss that is partly aesthetic—“because we have marred a great, mad, profligate work of art, taken a hammer to the most perfectly proportioned of sculptures.”

The inhabitants of modern industrial society burn the preponderance of the fossil fuels that the world uses in their cars, homes, and factories. The United States alone is responsible for about 25 percent of the world’s CO2 emissions, the rest of the industrial countries for about 20 percent, the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe for some 19 percent.4 “Over the last century,” McKibben writes,

a human life has become a machine for burning petroleum. At least in the West the system that produces excess carbon dioxide is not only huge and growing but also psychologically all-encompassing. It makes no sense to talk about cars and power plants and so on as if they were something apart from our lives—they are our lives.

Some commentators, adopting a position that McKibben calls defiance, propose that the pattern of life based on fossil fuels can be maintained. Some claim that the greenhouse effect will be offset by physical feedback mechanisms: for example, more evaporation from lakes and oceans will produce greater cloud cover, which will in turn shield the earth from the warming sun. Others subscribe to the so-called Gaia hypothesis—that the earth’s biosphere is like a live organism, a self-correcting homeostatic mechanism—and contend that living systems will automatically moderate the warming, precisely in response to its perturbations. Others suggest that the consumption of fossil fuels be offset by nuclear power. Still others propose new technical fixes—for example, giant umbrella-like satellites to cast shadows on the earth, or genetic engineering to adapt life to the greenhouse.

However, the tactics of defiance are beset by flaws. Even if the Gaia hypothesis is true, the time scale for Gaia processes is measured in millions of years, too slow to counter human-induced greenhouse effects, whose time scale is measured in decades. And while Gaia processes may preserve life, that life will not necessarily be human. James Lovelock, the chief proponent of the Gaia hypothesis, has remarked,

Gaia is no doting mother, no fainting damsel. She is a tough virgin, 3.5 billion years old. If a species screws up, she eliminates it with all the feeling of the microbrain in an ICBM.

The replacement of coal-fired generating plants by nuclear power plants may help some, but—safety and waste disposal problems aside—they would cut CO2 emissions in the United States by only about a quarter. People could stop cutting down trees and could replant the forests, but the American sycamore seedlings required to absorb a half century’s worth of the CO2 emitted by the world’s burning of fossil fuels would occupy a land area the size of Europe.

To McKibben, the main flaw in these arguments is that they all seek to maintain man’s material advancement, to continue his dominion over nature; they assume that man is, and should remain, the center of creation, and can do whatever pleases him. The ultimate distillation of that flaw is genetic engineering. McKibben chides man for proving himself, if only by accident, to be God’s rival, “able to destroy creation,” and for presuming, now and deliberately, to become God’s equal, himself a creator. McKibben notes that while today scientists implant genes from one species into the embryos of others, creating transgenic mice, pigs, rabbits, and fish, tomorrow they may engineer artificial plants, or chickens without extremities and lamb chops without bodies, or people designed to eat wood or live in outer space. Such prospects would be “the second end of nature.” The word “rabbit” will be meaningless. “‘Rabbit’ will be a few lines of code, no more important than a set of plans for a 1940 Ford.” Worse, man will be “in the deity business,” without humility.

Humility counts with McKibben—humility toward nature, toward the fields, the trees, toward other species. Economic and social necessity may compel human beings to reduce their use of the atmosphere as a sewer for gaseous effluents, but it will not necessarily force humility upon mankind, force them to reject the drive for dominion over nature. McKibben urges us to turn away from the arrogant and ubiquitous subordination of nature to human needs. He believes such a turning to be possible, since people lived in New York City without air conditioning for generations. And he holds it to be spiritually preferable, since a relentless drive for material domination leads to a “genetically engineered dead world.” While some verses in the Bible tell man to subdue nature, taken as a whole it counsels the cultivation and keeping of the land, the love of it. God—“if there is or was any such thing as God”—wants “to see if we take the chance offered by this [greenhouse] crisis to bow down and humble ourselves, or if we compound original sin with terminal sin.” To forestall the greenhouse hazards, our way of life and our thinking must change.

The key change advocated by McKibben is to recognize that nature deserves to be preserved for its own sake, not for ours. The idea, advanced in recent years by animal rights activists and “deep ecologists” among others, rests on the premise that nature itself has rights, and on the corollary that we, being only one species among many, have no intrinsic authority over any others, or even over rocks. 5 McKibben observes that what is environmentally sound—say, damming a river to produce “clean” electric power—is “not the same as natural.” The dam disrupts wildlife and inundates the valley behind it. Dave Foreman, of the deep ecology group Earth First!, admonishes that you protect a river because “it has a right to exist by itself,” adding, “The grizzly bear in Yellowstone Park has as much right to her life as any one of us has to our life.” Before learning about the greenhouse effect, McKibben thought such ideas were extreme; now he sympathizes with them, holding them to be “at least plausible.” He now willingly entertains the admittedly “disturbing” and “radical” idea that “individual suffering—animal or human—might be less important than the suffering of species, ecosystems, the planet.”

However, to establish an ecosystem’s suffering as more important than human suffering is to embrace a radicalism that is ruthless (although that apparently does not trouble some biocentrists: for example, David M. Graber, a biologist in the National Park Service, unabashedly declares that a free-flowing river has “more intrinsic value…than another human body, or a billion of them”).6 McKibben’s eagerness to preserve the inhuman in nature leads him to a position that—perhaps without his realizing it—is inhumane. It has also led him to entertain wild predictions concerning genetic engineering. The prospect of living in a genetically engineered world sickens him, but his version of that world—a world in which wingless and legless chickens were tolerated—would sicken most other people too, including most molecular biologists, who would see such feats as neither technically nor morally desirable. His love of nature also seems to have made him generally inattentive to the reality that for many people today—and for most people throughout most of history—nature has been not benign but harsh, not safe but dangerous. If today the Adirondack woods provide spiritual sustenance, it is because man—civilization—has tamed the wild enough to make it comforting.

More important, the declaration of deep ecologists that nature possesses rights coequal with those of man poses perplexing problems for political democracy. Are the rights of a free-flowing river absolute? Can it flow freely over, say, a farmer’s crops and house? If not, we are placed at a loss, since rivers and grizzly bears are unable to negotiate with us the boundaries of their rights and ours. Political democracy knows how to adjudicate conflicts between human groups about their respective interests in nature, but it has no calculus for weighing the rights of nature as such against the rights of man. Indeed, since nature cannot speak for itself, its “rights,” if they exist, must necessarily be interpreted by human beings, refracted through human sensibilities, defined in ways that express human perceptions and interests. All this is perhaps to say that moral and public policy questions concerning the preservation of nature are not biocentric but anthropocentric, and that they are unnecessarily burdened by injecting into them claims that nature possesses intrinsic rights.

Yet McKibben is as least as much anthropocentric as he is biocentric. His sermonizing on the rights of nature is a pained cry of apprehension not only for its fate but for ours in relation to it, and an eloquent call for action not only for its sake but for ours. He declares,

The only thing we absolutely must do is cut back immediately on our use of fossil fuels. That is not an option; we need to do it in order to choose any other future.

It has been predicted that if the world does nothing to slow the emission into the atmosphere of CO2 and CFCs, we will be committed by the year 2000 to a global warming of up to 4.7 degrees Fahrenheit and by the year 2030 to one almost twice that. McKibben and his wife have altered their lives somewhat to impede a greenhouse future—riding their bikes instead of taking long vacations in the car, installing thermopane windows, keeping the house at 55 degrees, trying to grow more of their own food. Yet he knows that these restraints, even if many were to adopt them, are just gestures, inadequate to the magnitude of the crisis. The acid rain and the warming that will kill the Adirondack trees have their causes everywhere. He writes, “the greenhouse effect is the first environmental problem we can’t escape by moving to the woods. There are no personal solutions.” The longstanding environmental slogan—“Think globally, act locally”—has to be modified in the greenhouse age to include global action.

But—what might not be evident from a mention on The Cosby Show—it can be hazardous to establish a public policy based on scientific theories that are both global and uncertain. One thinks of theories of racial degeneration—widely accepted in their day but eventually recognized as utterly wrong—that led to the policies of eugenics; or, more recently, of theories of the energy crisis—partly mistaken, at least for the near term—that had the world soon running out of fossil fuels. Such theories often entail limitations on individual rights—in the case of eugenics, a cruel and socially prejudicial infringement of the right of reproduction—for an allegedly larger public good. Mindful of the hazards, Andrew Solow, a statistician at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, has said of the contention that we will be too late if we wait to do something about the greenhouse effect until we are sure of it: “This argument applies equally to an invasion of aliens from space. More seriously, this argument neglects the costs of overreaction now.”

Still, the United States, for the better part of the 1980s, has been using the costs of overreaction as an excuse to do very little. Rowland and Molina advanced their theory of ozone depletion in 1974, and in 1978, the United States banned the use of CFCs; in 1981, however, Anne Burford, the head of the Environmental Protection Agency in the new Reagan administration, made a sharp right turn against any further CFC restrictions, suggesting that the predictions of ozone depletion amounted to scaremongering.7 Reagan officials also disparaged the greenhouse effect, questioning its validity, and the warnings of global danger. At a House hearing in March 1981, Congressman Albert Gore, of Tennessee, asked N. Douglas Pewitt, a physicist from the Department of Energy, whether he felt that research was urgently needed to determine whether the global warming was already happening. Pewitt replied, “No,” adding, when pressed by Gore, that he had a responsibility in running a scientific research program not to be “alarmist.”

The discovery of the ozone hole over Antarctica jolted the United States into agreeing, in September 1987, to the Montreal Protocol, which provides for an eventual worldwide reduction in CFCs of 50 percent. Once the hot weather and droughts started in the Eighties, even Reagan officials acknowledged that global warming was at least a potential problem, and in the 1988 campaign George Bush promised to convene a major White House conference on the issue during his first year in office. However, the conference remains to be called, and, in November of this year, at an international meeting in the Netherlands, the United States refused to commit itself to the stabilization of the emission of greenhouse gases by the year 2000. Bush administration officials insist that more research is needed, not only into the greenhouse effect as such but also into the likely social and economic consequences of dealing with it, especially by drastic limitations on the burning of fossil fuels.8

The response in 1987 to ozone depletion might suggest that the world can respond to predictions of environmental danger that are somewhat uncertain. However, the response required the jolt of 1985 and it involved limitations on just one family of chemicals, for which substitutes could be found. (The prospect permitted the DuPont Corporation to announce, in March 1988, the month in which the United States ratified the Montreal Protocol, that it would cease the manufacture of CFCs as soon as alternatives became available.) The course and consequences of global warming are scientifically more problematic and complicated than those of ozone depletion. More important, the imposition of limitations on the emission of CO2 poses vast difficulties for the world precisely because, as McKibben says, everyone’s life and expectations are so entwined with the burning of fossil fuels. The difficulties also include questions of equity: How should the costs of restricting CO2 emissions be borne across classes within the industrialized nations and between those nations and the poor nations?

Third world leaders want industrial development, automobiles, larger croplands—everything obtainable from the burning of fossil fuels and the clearing of forests. The Chinese have the most abundant coal reserves in the world and no doubt believe that they also possess the right to exploit that resource for their material advancement. The entire third world is currently responsible for only 35 percent of CO2 emissions.9 To attempt to reduce worldwide emissions by imposing what would amount to a direct fixed-percentage tax would be to maintain the first world’s preponderant share of fossil-fuel usage, to continue the existing ordering among the have, have–less, and have–not nations. McKibben rightly notes,

The thought that people living in poverty, be it desperate poverty or just depressing poverty, will curb their desire for a marginally better life simply because of something like the greenhouse effect is, of course, absurd.

Or, he might have added, because of something like ozone depletion. A speedup in the rate of CFC reduction—agreed to by the United States and several European nations in March 1989—is opposed as too costly by developing countries and by the semideveloped Soviet Union.

Equity would seem to require greater limitations on the first world’s CO2 emissions than on the third world’s. We would have to share our wealth, live with less. McKibben says, “It is politically—and humanly—impossible to say that the poor should be condemned to live without while we live with,” adding, “We don’t need to choose between cruelty and the greenhouse effect; there are more rational, if more difficult, ways to show our love of our fellow man.” The details of the greenhouse effect—just how great the warming will be, and how rapid—are debatable; the magnitude of its threatening consequences would seem to warrant prudent action, including, at the least, the development of alternative energy sources, improvement of energy efficiency, and attempts to slow population growth.

None of these steps is drastic; they were in place at the time of the energy crisis; they would conserve energy sources, too. Yet they represent more action than the Bush administration has had the courage to undertake. The United States, the world’s greatest CO2 polluter, ought to be leading, not retarding, a worldwide movement for reduction in the emission of greenhouse gases.

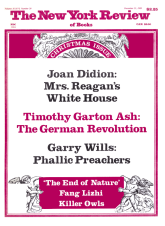

This Issue

December 21, 1989

-

1

The paper, an extract from a more extensive version that had been presented to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, December 11, 1895, appeared in the Philosophical Magazine, 41 (April 1896), pp. 237–276.

↩ -

2

Anne Taylor Fleming, “Turning Stars Into Environmentalists,” The New York Times (October 25, 1989), p. C 8.

↩ -

3

Both McKibben and Schneider draw on a three-volume report of the Environmental Protection Agency that was published in late 1988 under the title The Potential Effects of Climate Change on the United States.

↩ -

4

Christopher Flavin, Slowing Global Warming: A Worldwide Strategy, World-watch Paper 91 (Washington, DC: World-watch Institute, October 1989), p. 8.

↩ -

5

See Roderick Frazier Nash, The Rights of Nature: A History of Environmental Ethics (University of Wisconsin Press, 1989).

↩ -

6

Graber, in a review of McKibben’s book, Los Angeles Times Book Review (October 22, 1989), p. 9.

↩ -

7

The political odyssey of the ozone issue is ably recounted in Sharon Roan, Ozone Crisis: The Fifteen-Year Evolution of a Sudden Global Emergency (John Wiley, 1989).

↩ -

8

Los Angeles Times (November 7, 1989), p. A 6.

↩ -

9

Flavin, Slowing Global Warming, p. 8.

↩