In a famous eighteenth-century Japanese document, entitled Hagakure, there is one passage I find particularly arresting. In it the author, an elderly samurai named Yamamoto Jocho, advises his readers, presumably young followers of Bushido, or Way of the Samurai, to always “carry rouge and powder with one,” for “after rising in the morning, or after sobering up, we sometimes find that we do not look very good. In such a case we should take out the rouge and put it on.” This, he went on, is especially important when going out to do battle, for one must be beautiful even in death.

Yamamoto wrote his tract setting out the rules of warriorhood at a time when Japanese warriors had little else to do but worry about rules, appearances, style, for the major battles had been fought and the time was set for almost three centuries of uninterrupted peace. The old samurai was evidently worried that peace would sap the manly virtues of the warrior caste and wished to make sure the young retained their vigor through constant training of body and mind. The inevitable happened, however: warriorhood without wars was soon reduced to a set of stylish postures, adding another form of theatrical behavior to a period already so rich in dandyism. The Hagakure enjoyed a brief revival in the hands of one of the great dandies of our time, the late Mishima Yukio, who used it to castigate the decadence of postwar Japan.

Lord Baden-Powell, affectionately known as B-P, hero of Mafeking and the World Chief Scout, approved of Japan and of the samurai spirit in particular. There was nothing unusual about this, for many Edwardians found much to admire in a Spartan code that extolled such virtues as self-sacrifice, obedience, bravery, and comradeship. The Russo-Japanese war of 1905, when the great Russian bear, so it was thought, was defeated through sheer Japanese pluck, elicited considerable enthusiasm in Britain, and B-P was especially impressed by the way Japanese soldiers were prepared to blow themselves to bits for their emperor and country.

In this, as in so many enthusiasms (building empire, disciplining boys, shooting animals, etc.), Baden-Powell was a man of his time. Less common perhaps, though by no means completely eccentric, was his love of acting in drag, which he called skirt-dancing. Possibly related to this, and if not then certainly to Yamamoto Jocho’s philosophy, was a curious personal habit noted in Tim Jeal’s superb and exhaustive biography. Even during the partly self-inflicted rigors of roughing it in the African veldt, B-P insisted on using scented soap in his collapsible bath tub.

It is a small detail, but it seems so at odds with B-P’s cultish adherence to what he called “the flannel shirt life,” that peculiar predilection of hearty English gentlemen to revel in discomfort, and at such complete variance with his often stated fears of effeminacy, that it makes one wonder. Is there a point at which machismo turns into its opposite? And if so, did B-P, like Yamamoto’s samurai (not to mention Mishima), cross that line?

Jeal’s notes on the Chief Scout’s acting career suggest that he did, rather often in fact. Baden-Powell was essentially a man of the theater. His was a life of poses, fancy uniforms, strange oaths, flowery speeches, medallions, mottoes, and jamborees. The most famous Boy Scout maxim, “Be Prepared,” reflected the Chief’s narcissism. Great military men are often great poseurs, which doesn’t necessarily make them closet sissies. But there does seem to be a lot of muscle flexing for the benefit of mama (as in B-P’s own case, there is usually a great mother hovering closely behind our great heroes). Certainly, skirt-dancing is a venerable masculine tradition in Britain, still carried on in some very rough pubs. And yet, to one not raised in that tradition, some of B-P’s theatrical roles suggest a strong feminine streak in the old scout which, combined with an equally strong fear of females, could help one to explain, without wishing to be too Freudian, his general attitudes to life and politics.

B-P’s theatrical talents were already in evidence as a schoolboy at Charterhouse. His role as Mrs. Bundle, the waterman’s wife, was so much admired that the butler in his house saved part of his dress. One of his more romantic roles in an army production was as a Guardsman named Tosser who falls in love with Penelope, played by a young officer by the name of Kenneth McLaren, whom B-P judged a “wonderfully good lady.” Tim Jeal’s description of the play is one of the more amusing passages in his book. “I’d choose to be a daisy if I might be a flower,” sang Penelope, as she entered the stage. “Where can Penelope be?” exclaimed the love-struck Tosser. “I am longing to embrace her.” One can be sure that much hearty fun was had by all.

Advertisement

B-P took McLaren under his wing and would henceforth refer to him affectionately as “the Boy.” This relationship might well have been the closest he ever enjoyed with anyone apart from his mother. When the Boy was captured by the Boers, while B-P was holding the fort at Mafeking, B-P wrote to him daily (such still were wars in those days) and consoled himself by looking at photos of the Boy on his desk. It is hardly surprising, then, that when the Boy finally decided to get married, his wife found little favor in B-P’s eyes. And when B-P himself, after years of procrastination, got married at the age of fifty-five, his bride, Olave, declined to invite the Boy to their wedding. The arrows of jealousy will find their target, even if those of Eros are denied.

Which begs the inevitable question: Was B-P a closet queen? The question has been raised so often, about so many imperial old boys (Kipling, Lawrence, etc.), that this angle has become a bit of a cliché. Still, in B-P’s case the pointers are hard to ignore. One of the strengths of Jeal’s book is that he seriously explores the evidence, without being prurient, sensational, or boring. To begin with the greatest cliché of all: the Mother.

Henrietta Grace was by all accounts, including Jeal’s, rather a monster, who commanded, and duly received, her sons’ absolute devotion, as well as a considerable chunk of their incomes to keep her in the style to which she had accustomed herself. Her main aim in life was what she called “getting on.” Jeal begins his chapter on Henrietta Grace, aptly entitled “That Wonderful Woman,” with a quotation from her most famous son: “The whole secret of my getting on lay with my mother.”

Getting on in British society, then as now, meant doing battle in the class war, in the case of the Baden-Powells, battling to move from middle to upper class. This in itself involved a large amount of theater. The family name, for example: Powell was changed by H. G. to the more distinguished sounding Baden-Powell (that all-important hyphen) by attaching her husband’s first name, Baden, to his surname. Baden had the added advantage of sounding vaguely Germanic; an advantage because of the German connection of the Royals and the then fashionable association with Teutonic vigor. When this association lost its shine later in the century because of Germany’s increasing rivalry with Britain, more stress was laid on the Powell side. H.G. even laid claim to a bloodline that went back to Athelystan Glodrydd, Prince of Fferlys, whoever he may have been.

Getting on meant living beyond the family means, but since Mrs. Baden-Powell was absolutely “determined not to make any new friends unless very choice people indeed,” this sacrifice had to be bravely born. The house in London, indispensible for wining and dining the highest and mightiest available, was maintained at vast expense, severely cramping the styles of H. G.’s sons for most of their lives. But it must be said in H.G.’s defense that her strategy paid off: the family, particularly through the efforts of B-P, got on, at the price, of course, of a permanent social neurosis, but that is the normal British condition to this day. B-P’s fondness for camping out in Asian deserts and African veldts was a welcome and in his time customary respite from the class war back home.

The presence of formidable mothers is generally not a help in the battle of the sexes, to be sure, but it does not automatically drive sons into the arms of boys either. To his credit, Jeal does not say that it did. He finds stronger evidence for B-P’s desire for his own sex (in the mind, if not actually in the camp bed) elsewhere. But even there, where the indications seem most obvious, one must bear in mind that what may strike a modern reader as homosexual behavior often was not regarded as such by a man of B-P’s class and time.

Take, for instance, the case of the photographs. B-P had an old friend (Rifle Corps and Football First Eleven) called A.H. Tod, who taught at Charterhouse after retiring from the army. One of Tod’s amusements was to take the boys out and photograph them in the nude. His work can no longer be seen, alas, for the pictures were destroyed in the late 1960s, supposedly to protect Tod’s reputation. But Jeal quotes one source describing them as “contrived and artificial as regards poses”—Charterhouse boys as Greek athletes, perhaps, throwing javelins, or dancing between the trees like fauns. In any event, they were much admired by B-P and visits to his alma mater were preceded by pleasant anticipation of another peek at his friend’s art.

Advertisement

It is possible of course that B-P’s interest was purely artistic and it is true that fondness of the male nude was as conventional among the late Victorians as, well, skirt-dancing. B-P’s enthusiasm for naked men went further than art, however. During the Great War he took great pleasure in watching soldiers “trooping in to be washed in nature’s garb, with their strong well-built naked wonderfully made bodies.” This, too, would not be necessarily significant if it were not for his equally pronounced distaste for the female body (“pinkish, whitish, dollish women”), or indeed anything to do with female sexuality. Interest in girls, which, despite his warnings, he could not fail to note among many young men in his charge, he regarded as a temporary disease (“girlitis”). It would soon pass, he was convinced, with a sufficient regimen of the flannel-shirt life. Masturbation was of course the very devil’s work, and sex to him, though unfortunately indispensible for procreation, was so much “beastliness.” No wonder he suffered constant migraines—not to mention torrid dreams of soldiers putting their hands in his pocket—during the time he dutifully cooperated in the production of three children. No wonder his headaches ceased the moment he forsook the marital bed for the more rugged quarters of his balcony.

Added up, these various horrors and fancies do indeed lead somewhere near the conclusion drawn by Jeal that B-P was a repressed homosexual who sublimated his desires on a grand scale. There is a school of thought, gaining currency among some conservatives, that the Victorian repression of sex was not such a bad thing, since, as in the Chief Scout’s case, it resulted in prodigious creative energy. Jeal, though neither a prig nor especially conservative, lends support to this argument:

When a gifted man’s deep anxieties about his sexual nature and his personal manliness coincide with a nation’s fear of impending decline through lack of virile qualities, the basic ingredients exist for a remarkably potent creative brew.

Indeed so. But a potentially dangerous one, too, for it is the brew from which great dictators emerge.

Which leads us to the next question about B-P, and others like him: Was he a proto-fascist? Were the Boy Scouts part of the same brew as Hitler Youths? Leftist debunkers of the Chief Scout’s mythology have argued that he was, though admittedly not a murderer, certainly a racist, authoritarian, reactionary breeder (if that is the right word) of cannon fodder for a belligerent empire. The best-known book to make this case is The Character Factory by Michael Rosenthal, a Columbia University professor.1 One of the aims of Jeal’s book is to debunk the debunkers, specifically Mr. Rosenthal.

He largely succeeds, B-P was no more racist than most Englishmen of his time, indeed in many ways less. Jeal has little trouble attacking Rosenthal’s rather conventional “progressive” view that B-P was a conservative elitist, for the Chief Scout’s ideals were far from conservative; in fact, they were rather radical, having much in common, as Jeal says, with Fabian socialism and the aesthetic politics of John Ruskin. And if the sight of uniformed boys swearing oaths around campfires strikes one as particularly right wing, one might ponder the fact that these spectacles are most common in the few people’s republics still remaining. But Jeal’s main line of attack against the progressive debunkers is to argue that B-P did not intend to breed “militarists” so much as “good citizens.”

This may be missing the point, for what are good citizens? Good citizens of Sparta were not like those of Athens. B-P himself had some strong ideas on the subject. Jeal quotes from a pamphlet written by the hero of Mafeking in 1907 to promote the idea of “Peace Scouts”:

The main cause of the downfall of Rome was the decline of good citizenship among its subjects, due to want of energetic patriotism, to the growth of luxury and idleness, and to the exaggerated importance of local party politics.

This is not a recipe for militarism, to be sure, but like many radicals of various persuasions, Baden-Powell associated party politics, materialism, commerce, intellectualism—in short, urban life—with decadence. He sought to stop the rot by, so to speak, throwing away the books and making for the bush. Typically, he believed that the virtuous pioneering spirit of America had been destroyed by “over-civilization.” Like Ruskin, and, it must be said, many romantic fathers of political extremism, he had a profound contempt for the bourgeoisie, possibly because they stood for a society which forced him to suppress his most hidden desires. And so he dreamed of a premodern order of purity, self-reliance, comradeship, and discipline. Jeal’s argument that B-P’s Boy Scout Movement didn’t have military aims may be quite correct, in fact, is correct; what the Chief Scout aimed at was to revive the warrior spirit in peacetime, rather like the old samurai and his Bushido. Indeed he went further, he hoped to achieve world peace and brotherhood through the warrior spirit. Despite his old-fashioned notions of patriotism, he was as much of an internationalist as the most ardent Marxist.

In the class war, though getting on all right himself, he wanted his movement to transcend class, just as he wished it to transcend race and nation. As for Empire, his ideals led to an interesting dilemma, felt by many a British adventurer in the bush. For there was B-P, in Africa, ostensibly to civilize the natives, while in many respects admiring their customs more than the flabby ways of the white man. He deplored, quotes Jeal, the destruction of “the tribal system of training and discipline” to make way for the “widespread provision of cash wages, bad temptations, and such teachings of civilization as they can gain from low class American cinema.”

Those bad temptations just won’t go away! To help his scouts resist them, he found some use for the tribal folklore he had picked up among the natives; blowing the koodoo horn at morning call, handing out African amulets for special merit, that sort of thing. Perhaps the Way of the Tribal Warrior was better than the wage-earning, movie-going, party-voting booboisie back home, but surely members of the latter were closer to our definition of good citizens in a modern democracy.

It is true that much of B-P’s tribalism was boyish, not to say infantile, more than it was sinister. Pictures of the old Chief Scout in shorts, surrounded by his loyal scoutmasters (his “Boy Men,” as he called them), roaring with good clean hearty laughter, suggest not so much fascists as outsize boys who refuse to grow up. It was a common Victorian and Edwardian affliction. B-P was apparently so moved by James Barrie’s Peter Pan that he went to see the play on consecutive nights. The koodoo horn, the amulets, the campfire yarns, the lusty community singing: Jeal is surely right that “for many men, Baden-Powell among them, the Boy Scouts provided a blessed illusion of reclaiming their stolen childhoods.”

But was B-P’s movement really quite as innocuous as Jeal says? Was it really all boyish romance “in a different moral world” from the National Socialist and Communist youth movements of the 1930s? And if it was, was this a matter of circumstances or because “the fundamental moral ideals of the two organizations could hardly have been more distinct.” I am not quite as sanguine about this as Jeal appears to be, for I am more inclined to think that B-P’s brand of back-to-naturism, tribal nostalgia, and youth worship always contained a kernel of noxious idealism, which, if it had developed under different conditions, might well have ended up in the same moral world as the Hitler Youth or the Red Pioneers.

Still, despite B-P’s brief flirtation with the ideas of Hitler and Mussolini (not as unusual in the Thirties as some people like to believe), his boy scouts never become tools of an authoritarian state. B-P’s movement was more akin to the German Wandervögel, city boys mooning about with rucksacks, trekking through forest and dale, letting the mountains echo with their soulful folk songs. Like B-P, they rejected “over-civilization,” politics, city life; they, too, made a cult of the flannel-shirt life, of nature, of youth. They were consciously antipolitical. As one enthusiast observed:

Does not political activity all belong to that urban civilization of yesterday, from which we fled when we set up our community of friends out in the forests? Is there anything more unpolitical than the Wandervogel? Were not the Meissner festival and its formula a repudiation of the party men who were so anxious to harness youth to their political activities? Is not the sole task of the Free German communities to educate free, noble and kind people?2

Instead of politics there was a cult of beauty, male beauty. This was splendidly recorded in Herbert List’s photographs of blond nature boys sitting on rocks or bathing in lakes—rather similar, one imagines, to the pictures taken by B-P’s Charterhouse friend. The pure idealism and antipolitical nature of the Wandervögel movement were what made it so attractive and so vulnerable to political manipulation, for in time the celebration of youth, of nature, of male comradeship, of anti-urban, antibourgeois sentiment was harnessed to a most sinister cause, which also insisted on being above party politics—though not nation or race—in the name of a beautiful new order. One figure to emerge from the Wandervögel was Baldur von Schirach, leader of the Hitler Youth. Descriptions of him sound a familiar note:

a big, pampered boy of good family who laboriously imitated the rough, forceful style of the boys’ gang. His unemphatic, rather soft features held a hint of femininity, and all the time he was in office there were rumours about his allegedly white bedroom furnished like a girl’s.3

There is no evidence that Schirach was homosexual, or that male femininity, any more than the presence of great mothers, is a clear sign of homosexuality, or that homosexuals are any more attracted to extreme ideals or antipolitical romanticism than heteros. But there is a connection between authoritarianism and communities based on male bonding, particularly when they seek to replace or at least put themselves above politics, family life, in short, the boring booboisie. This is sometimes forgotten in our own enlightened times by those who see the bourgeois family as uniquely oppressive and homosexuality as a liberating force. It can be thus, but it can also be the other way round: family loyalty, as all totalitarian regimes well know, is a great obstacle to state control, whereas the collective loyalty of bonded males is often a help. It is also true that some of the more notorious leaders of boys’ bands (Gabriele D’Annunzio, Oswald Mosley) were not homosexuals; but on the contrary compulsive womanizers, but this is really no more ironic than B-P’s neurotic homophobia or the vicious persecution of homosexuals in Hitler’s Reich.

The best examples of overt homosexual authoritarianism are the samurai and the Dorians. In a recent book on Japanese homosexuality, the Japanese authors4 lament the passing of the aesthetic cult of boy-love (shudo), upon which, they say, the Way of the Samurai was based. The Way of Boy-love specifically promoted the loving submission of beautiful boys to more experienced men. What destroyed this unique system of beauty, loyalty, and male nobility, were those old enemies of the romantic mind, capitalism and industrialization. As they put it rather charmingly: “Modernization resulted in beauty being taken over by women!” Why? “Because in traditional societies one regarded oneself as being, while in the modern, one sees oneself as having.” One was born an aristocrat or a peasant, and an aristocrat had to be more beautiful than the common man, whereas the modern bourgeois have “no need of being beautiful themselves, They relate themselves to beauty by ‘having’ a beautiful woman.”

So much, then, for the modern view of seventeenth-century Japan. What about this poem composed in Greece by Theognis, in the sixth century BC:

You want to buy an ass? a horse?

You’ll pick a thoroughbred, of course,

For quality is in the blood.

But when a man goes out to stud—

He won’t refuse a commoner

If lots of money goes with her.5

Theognis was deeply worried about modern decadence and advocated boy-love, discipline, and hierarchy to preserve the noble traditions of the past. As his translator put it:

He presents to us the distress and confusion of those who live in an age of transition from one set of values (based on agrarian, hereditary nobility) to another (based on money and the city).

The distress and confusion of Victorian gentlemen, particularly those on the fringes of nobility with aspirations of getting on, were just as acute. Likewise with Japanese dandies pining for the samurai past, or even perhaps Edwardian aesthetes falling in love with one another and Stalinism in Cambridge. Walter Pater, one of Oscar Wilde’s mentors, drew the comparison between the Dorians and Victorian England. Dorian youth, he wrote, left early the mushy comforts of the suburban home to be educated in public schools:

It involved however for the most part, as with ourselves, the government of youth by itself; an implicit subordination of the younger to the older, in many degrees…. [They ate] not reclined, like Ionians or Asiatics, but like heroes, the princely males, in Homer, sitting upright on their wooden benches;…[They] “became adepts in presence of mind,” in mental readiness and vigour, in the brief mode of speech Plato commends,…with no warm baths allowed; a daily plunge in their river required…. Youthful beauty and strength in perfect service—a manifestation of the true and genuine Hellenism, though it may make one think of the novices at school in some Gothic cloister, of our own English schools.6

This, much more than the Teutonic earnestness and racism of the Hitler Youth, would have appealed to B-P and his Boy Men. “Youthful friendship ‘passing even the love of women’…became an elementary part of their education. A part of their duty and discipline.” Indeed, indeed. And if such a system weighs heavily on individual freedom and, in times of peace, “may be thought to have survived the original purpose,” well, says Pater, “An intelligent young Spartan may have replied: ‘To the end that I myself may be a perfect work of art, issuing thus into the eyes of all Greece.’ ”

B-P was himself a work of art, in the eyes of his mother, in the eyes of all the world. And in being so he gave many boys much innocent pleasure. He never was a fascist, but his ideals lent themselves to fascism elsewhere. Britain was too bourgeois to turn into a Sparta and the aggressive energies of youth had a ready outlet in the Empire. As B-P observed:

This nation does not need more clerks in the overcrowded cities of this little island…. No! The nation wants men and wants them badly, men of British blood who can go out and tackle the golden opportunities, not merely for benefiting themselves, but for building up and developing those great overseas states of our Commonwealth.

Those days are over now. We live in meaner times. One shudders to think what might happen if the energy of British youth, jobless, ill-educated, ready for any action, were to be turned to some great cause, against the clerks whom B-P so despised. One can already hear the words of salvation in the mind of some future Spartan: discipline, sacrifice, comradeship—Be Prepared!

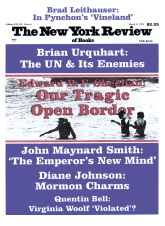

This Issue

March 15, 1990

-

1

Michael Rosenthal, The Character Factory: Baden-Powell and the Origins of the Boy Scout Movement, (Pantheon, 1986). Rosenthal’s book was critically appraised in the New York Review (June 26, 1986), by Geoffrey Wheatcroft, whose arguments were rather similar to Jeal’s.

↩ -

2

Quoted in Joachim C. Fest, The Face of the Third Reich (Pantheon, 1970), p. 224.

↩ -

3

Joachim C. Fest, The Face of the Third Reich, p. 227.

↩ -

4

Tsuneo Watanabe and Jun’ichi Iwata, The Love of the Samurai: A thousand years of Japanese homosexuality (London: GMP Publishers, 1989).

↩ -

5

Translated by Dorothea Wender, in Hesiod and Theognis (Penguin Classics, 1973).

↩ -

6

Walter Pater, Plato and the Platonists, (London: Macmillan, 1893), pp. 199–201.

↩