To the Editors:

Julia Preston did a thorough and generally admirable job in explaining the latest developments in El Salvador [“The Battle for El Salvador,” NYR, February 1]. I was troubled, however, to read her insistence that “clearcut” evidence was now available to indicate that the Salvadoran rebels were receiving arms from the Sandinistas in Nicaragua.

I do not know whether the rebels do indeed receive any weaponry from the Sandinistas. What I do know however, is that no objective case has yet been made.

Let us start with the delivery to which Ms. Preston refers. “Days later reporters in Nicaragua learned, by interviewing Nicaraguans who lived nearby, that the aircraft left from the Sandinista military airfield at Montelimar,” reports Ms. Preston. Forgive me for asking, but just how did those Nicaraguans know where the planes they had seen take off had landed? The New York Times reported on November 26, 1989, that the documents found on the plane indicated it took off from Augusto Cesar Sandino airport in Managua. Well, which was it? It gets curiouser. If the plane was smuggling weapons from Nicaragua, why did it carry four passengers? Would you take along three passengers if you were smuggling weapons? Why did it contain “red and black” Sandinista markings, as if to announce its point of origin? That is not the way I would do it.

It is almost quaint to question whether the Sandinistas are supplying the Salvador rebels with weapons these days since virtually everyone in the US media assumes it to be so. But the fact is, the CIA and the Pentagon have not come up with one credible shred of evidence since 1981, when former CIA agent David C. McMichael says the spigot was turned off. This is hardly a minor point since interdiction of the alleged arms shipments were, it will be recalled, the original justification for the Reagan administration’s creation of the contras in the first place. (The contras, on the other hand, do sell their weapons to the rebels, as the Times has reported with concurring evidence.)

Since 1981, we have witnessed an Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs, Elliott Abrams, admit to lying about the United States role in the transshipment of weapons across Central America. We have heard of the lengths that former NSC member Oliver North went to to sell this disastrous policy, including dressing up some hapless Central American and sending [him] to Capitol Hill to impersonate a pro-contra Nicaraguan priest. It does not stretch my imagination to consider the possibility that some pro-Salvadoran elements either in this country or in Central America could have concocted this latest shipment as well.

Again, I emphasize that I have no way of knowing whether arms are in fact being shipped from Nicaragua to El Salvador. But if we have learned anything at all from Iran/Contra, Watergate, and Vietnam before them, it is that we are fools to take the word of our government in matters related to the foreign wars it conducts.

The Nicaraguan Ambassador to the United States has denied any role in the shipments in a letter to The Wall Street Journal. Until we see some evidence, it’s his word against that of the Bush administration. Take your pick. As for me, I am withholding judgment.

Eric Alterman

Washington, DC

Julia Preston replies:

Mr. Alterman is right to be skeptical about the matter of the clandestine supply of weapons to the Salvadoran guerrillas by Nicaragua. I dealt with this point too briefly in my piece. His questions give me an opportunity to detail the “objective case” more thoroughly.

The Cessna 310 I mentioned crash-landed, apparently after running out of fuel, in eastern San Miguel province on November 25. In addition to the twenty-five anti-air missiles, it was carrying four men, all wearing olive-green military uniforms. Two died in the crash and one died of his injuries shortly afterward. A local peasant, twenty-two-year-old Fredy Jesus de Garay, told reporters that he reached the scene in time to hear a single shot and find the fourth man dead with a fresh bullet wound in his temple. Garay was convinced that the man had commited suicide. The gun he apparently used was a 9mm Browning stamped “Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua,” a type of weapon left over from Anastasio Somoza’s arsenal, which is often issued to Sandinista air force and intelligence personnel.

It seems probable that this fourth man was acting under some kind of discipline requiring that he not be taken prisoner alive. As to the others, we can surmise that the pilot brought along at least one crewman to help unload the weapons speedily. It’s possible that the other two were passengers who intended to remain in San Salvador, perhaps to advise the Salvadoran rebels on the use of the missiles. (Remember, all this occurred in the heat of an offensive.)

Advertisement

Also found on the Cessna was a blank form from a Nicaraguan charter firm, SETA, which is based at Sandino International airport in Managua. Within forty-eight hours SETA officials interviewed by reporters in Managua confirmed they had owned the plane but said it had been sold several months earlier to a Managua bank controlled by the Nicaraguan government. Also on the Cessna was a hand-written flight plan and maps that led US intelligence analysts in San Salvador to conclude that the plane had taken off from Montelimar, a resort on the Pacific coast of Nicaragua where there is also a Sandinista military airfield.

Reporters were flown to see this Cessna on the day it crashed, in Salvadoran military helicopters, at the urging of US Ambassador William Walker. Their time on the ground was limited. On the whole the news copy from that tour shows that the reporters were careful about drawing conclusions from what they saw. The press was not persuaded of the Nicaraguan government’s involvement until new information turned up in subsequent days.

A second plane, a twin-engine Cessna, landed safely on November 25 in a field thirty-five miles southeast of San Salvador and was met by some sixty guerrillas who quickly unloaded a number of long green tubes, probably more missiles. But the second plane was unable to take off for some reason, and the guerrillas ordered local peasants to dismantle and bury it, which they were able to do only partially. News photographers got to the second aircraft before the Salvadoran military, so news accounts of that scene came entirely from local residents and guerrillas still in the area. Those witnesses said the plane displayed a marking in the Sandinista black and red colors.

Tips from San Salvador led reporters from The Washington Post and The Miami Herald in Managua to go to Montelimar to question residents and Sandinista militiamen near the airfield. The witnesses reported that they heard two planes take off about 3:30 AM on November 25 (about two hours before the first plane crashed in El Salvador). The Sandinista military gave the unusual nighttime takeoff special attention, sealing off the base and sending away militias normally posted there. The peasants judged that the planes were heavily loaded because one clipped an electrical wire near the field on takeoff, pulling down two light poles. The timing and details led the peasants to suggest spontaneously that the planes were the same ones that turned up in El Salvador.

A November 30 dispatch from Managua in the French newspaper Le Monde (hardly a mouthpiece of the Bush administration), citing high-level Sandinista sources, confirmed that the arms shipments originated in Nicaragua but suggested they were organized mainly by Cuba, with the help of members of the Sandinista military but without the approval of the nine top Sandinista comandantes.

Finally, when President Daniel Ortega went to the regional summit in Costa Rica in December, he avoided outright denials of Nicaragua’s involvement (as he had, conspicuously, throughout the episode) but instead sought to counterattack with new accusations against Costa Rica and Honduras for aiding the contras. But the evidence against Nicaragua was so strong, and thus Ortega’s position so weak, that he was obliged to sign an agreement relegating the Salvadoran guerrillas to the same political footing as the contras and condemning both groups for persisting in “irregular” warfare.

In the history of guerrilla war it is common for rebel armies to depend on arms supplies from outside allies. In the case of the Salvadoran guerrillas, the Reagan administration’s often unfounded claims generated an equally unrealistic reaction, in my view, among some American liberals who insisted that the guerrillas could prosper without such supplies and that the Sandinistas, after claiming their shipments had stopped, would never continue them and lie about it.

Since 1987 the Central American presidents have agreed among themselves that it is damaging to the prospects for regional peace for outside governments to support guerrilla movements. That standard seems to me a useful one to keep in mind when examining such allegations as those made in the case of the Cessna 310.

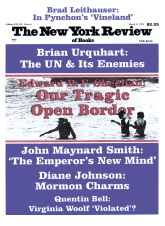

This Issue

March 15, 1990