In the beginning of Gore Vidal’s new novel, Hollywood, the “Duchess,” as the consort of Ohio senator Warren G. Harding is affectionately known, visits the Washington salon of the astrologist Madame Marcia to read her husband’s horoscope. The visit has been arranged by Harding’s henchman, Harry Daugherty, who is pushing him for the Republican nomination in 1920. Daugherty believes that his candidate will be nominated and elected, and he expects that Madame Marcia, who is consulted by the greatest in the land, will predict this, and that her prediction will be a good way of preparing the Duchess for her future role. Only Harding’s hour and date of birth have been supplied to the functioning sorceress, but since she has instant access to the Congressional Directory, a glance could allow her to match the date to the man. Or has Daugherty fixed her in advance?

Madame Marcia duly foresees the presidency in the stars and rampant lion of the horoscope. But she also sees a darker fate. In answer to the question: “He’ll die?” she replies:

“We all do that. No. I see something far more terrible than mere death.” Madame Marcia discarded her toothpick like an empress letting go her sceptre. “President Harding—of course I know exactly who he is—will be murdered.”

We are now in the world of Gore Vidal. Many years ago, although an avid reader of his novels, I was uneasy in some parts of that world. I remember waxing a bit hot under the collar, reading Burr, at what I considered a travesty of the character of my hero, Thomas Jefferson. But since that time the bottom has fallen out of my old world. We have undergone Watergate and Irangate; we have seen a president resign from office under fire and a daydreaming movie star occupy the White House. If I hear the truth spoken by an elected official or his representative, I wonder if he has had no inducement to lie. I have had to face the nasty fact that the world is—and probably always was—a good deal closer to the one so brilliantly savaged by Vidal than any that I had fondly imagined.

And even now, as I pause in writing this piece to glance at the newspaper, I read that the second volume of Robert Caro’s heavily documented life of LBJ will attempt to prove that that lauded Texas liberal was the greatest and most unabashed rigger of elections in our political history. We may yet live to see Vidal branded a sentimentalist!

Vidal has said that Hollywood is the last (though not the last chronologically) of a sequence of novels loosely called his History of the United States, starting with Burr, which deals with Aaron Burr’s conspiracy, jumping forward to Lincoln and the Civil War, pausing in 1876 to cover the scandal of the Hayes-Tilden election, then moving in Empire to the imperialism of Theodore Roosevelt, and ending in Washington, DC, with Joe McCarthy’s reign of terror. Hollywood fills in the First World War and the Harding administration. But if the novels are all stars, at least in the brightness of their dialogue and character delineation, they do not form a true constellation. I doubt that they were really conceived as such before the writing of Lincoln. I find a true unit only in the trilogy of Lincoln, Empire, and Hollywood, which relate the grim, dramatic story of the forging, for a good deal worse than better, according to Vidal, of the American empire and its ultimate conversion into the celluloid of the moving picture, which is all he deems it to be worth.

In Lincoln he finds the only man in his epic to whom he is willing to concede true greatness, and his portrait of his man raises the novel a head above the others of the trilogy and may even make it a significant addition to the mountain of books on the emancipator, many of which, in Vidal’s opinion, are packed with lies. His Lincoln is not so much concerned with freeing the slaves; he wants to save the union in order to turn it into a huge, world-dominating state, the “empire” that will be the subject of the next two novels. The book ends with John Hay musing on the question of whether the assassinated president might not have willed his own murder “as a form of atonement for the great and terrible thing that he had done by giving so bloody and absolute a rebirth to his nation.”

Vidal admires the creator but not the creation. He is constantly fascinated with the subject of power. Money, oratory, muscle, wit, and sex (the latter when not used exclusively for brief physical pleasure) are devoted to the domination of one’s fellow man. For what purpose? For the fun of the game. Vidal is something of an existentialist, suggesting as he does the absurdity of grand projects. Theodore Roosevelt in Empire exults in blood and guts and accomplishes nothing. The question is raised at the end of the novel if it is even he who has effected the things he has purported to effect. In a scene between the rough rider and the newspaper despot William Randolph Hearst, the latter suggests that the President has been his puppet.

Advertisement

“True history,” said Hearst, with a smile that was, for once, almost charming, “is the final fiction. I thought even you knew that.” Then Hearst was gone, leaving the President alone in the Cabinet room, with its great table, leather armchairs, and the full-length painting of Abraham Lincoln, eyes fixed on some far distance beyond the viewer’s range, a prospect unknown and unknowable to the mere observer, at sea in present time.

The two main characters, who weave the episodes of history into the narrative of Hollywood, Blaise Sanford and his half sister, Caroline Sanford Sanford, have settled an old family feud by agreeing to co-manage a Washington newspaper of wide circulation and great political importance. They have a genealogical connection with Charles Schermerhorn Schuyler, the narrator of Burr and 1876, who dies at the end of the eponymous year, which is worthy of a Jacobean tragedian. Schuyler’s daughter Emma, widow of the French Prince d’Agrigente, has plotted to marry the wealthy Colonel William Sanford after his wife has died giving birth to a child whose conception Emma knows will be fatal to her but which she has nonetheless wickedly encouraged. Mrs. Sanford duly dies giving birth to Blaise, and the next year Emma, now her successor, is justly punished by expiring at the birth of her own child, Caroline. The two babies are given a genetic head start to face the rigors of life in a Vidalian world.

Their creator has chosen the appropriate interpreters for his cool and unsentimental story. They are dedicated sophisticates, devoid of any prejudice and of any religious or even political bias, brilliant, charming, and quite as decent to others as others are to them, with wit, delightful manners, and a fixed determination to do anything they choose to do as well as it can be done. Above all, they aim to see the world as it is, no matter what conclusion that vision may entail. Caroline has been married to and divorced from a Sanford cousin, but her dismal, right-wing, red-baiting daughter and only child, whom she understandably dislikes, is the child of a former lover, US Senator Burden Day, another detached interpreter of the political scene. Sex in Vidalian fiction rarely gets out of hand. It is entirely physical, entirely for pleasure, and is indulged in with both sexes. Oddly enough, it is just the opposite of what it is in Proust, whom Vidal deeply admires, where it is identified with pain. Caroline’s brother Blaise, who is married to an heiress, has a brief homosexual encounter in Paris with a poilu turned prostitute, an episode that might be deemed the trademark of a Vidal novel, like the fox hunt in Trollope or the appearance of Hitchcock as an extra in each of his films.

Caroline takes leave of the Sanford-owned newspaper to explore the new phenomenon of Hollywood in 1917, where she becomes not only the mistress of a director, Tim Farrell, but the leading lady of his films, under the name of Emma Traxler. That a middleaged, world-famous newspaper woman should become a movie star without anyone recognizing her surely lacks verisimilitude, but in the dreamlike reality that Vidal so successfully evokes we are only too happy to accept it. Blaise remains, for the most part, in Washington, which allows the reader to follow two of the three themes of the novel: the involvement of America in war and the rise of Hollywood to world power, each through the eyes of a Sanford. The third theme, the why and wherefore of the election of Warren Gamaliel Harding, we follow through the mind of one of his crooked henchmen, Jesse Smith.

The Sanfords, of course, know everybody. Caroline fills us in on Hearst, Marion Davies, Elinor Glyn, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, the murdered William Desmond Taylor, and hosts of others, while Blaise introduces us to everyone of note in the capital from President Wilson down. It is an entrancing gallery of portraits, as funny as it is acute.

Wilson is the best, “an odd combination of college professor unused to being contradicted in a world that he took to be his classroom and of Presbyterian pastor unable to question that divine truth which inspired him at all times.” Eleanor Roosevelt, then wife of the assistant secretary of the Navy, is “the Lucrezia Borgia of Washington—none survived her table.” The malice of her cousin Alice Longworth, TR’s daughter, has “the same sort of joyous generalized spontaneity as did her father’s hypocrisy.” As it was an article of faith that the American public could not fall in love with a screen star who was married in real life, Francis X. Bushman, the father of five, is “obliged to pretend to be a virtuous bachelor, living alone, waiting, wistfully, for Miss Right to leap from the darkened audience onto the bright screen to share with him the glamour of his life.”

Advertisement

We see Wilson on board the SS George Washington, confiding to Blaise that he could have done well in vaudeville, and, to prove it, letting his face go slack and his body droop as he performs a kind of scarecrow dance across the deck singing: “I’m Dopey Dan, and I’m married to Midnight Mary.” We see Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks naked in a steam room discussing how they should have used some of their surplus earnings to buy the press and bury such Hollywood-damaging scandals as the Fatty Arbuckle affair. We see Mrs. Harding hurling furniture at her husband’s mistress and Alice Longworth doing hand-springs before her father’s admirers.

Whether we believe it all or not, it is always in character, always more than possible. When a character suggests that a woman as plain as Eleanor Roosevelt would never have hired as her secretary as beautiful a woman as Lucy Mercer to be brought in constant contact with her handsome husband unless she had been attracted to her herself, one’s first reaction may be one of shocked indignation, but then, when one pauses to consider it…. It is always that way with Vidal.

There are moments when a gathering of his characters takes on some of the features of a fancy dress party. One tries to identify each newcomer before he is introduced. Sometimes the characters are not. I think I spotted Rudolf Valentino in the young extra in a Hearst private movie who had “a square crude face” and eyebrows that grew together in a straight line “like those of an archaic Minoan athlete.”

Through conversations with the capital’s power wielders Blaise and Senator Day follow the slow enmeshing of a peace-loving president in the imbroglio of European war. “I do believe the Germans must be the stupidest people on earth,” Wilson groans as the submarine sinkings mount. But he is helpless against the U-boat and Allied propaganda, as he will be helpless against the Republican Senate majority to save his league. Vidal sees our involvement in the war of empires as a mistake and one that cost us essential liberties in the Red-baiting era that followed, but he does not see how the mistake could have been avoided. America in his view, ever since Lincoln forged his new union, had been ineluctably committed to the course of empire. Empires are not good things; they ruthlessly exploit weaker tribes, but at least in Europe, with its aristocratic traditions, the process is carried out to its inevitable dissolution with a certain style. America, on the other hand, being a mix of peasant emigrations, is easily victimized by any sort of propaganda and doomed to make an imperial fool of itself.

Caroline, the author’s primary spokesman, like her mentor Henry Adams (one of Vidal’s finest portraits) believes in nothing but “the prevailing fact of force in human affairs.” In Washington, where the game of force is played for its own sake and where morality is always relative to need, “one man’s Gethsemane might be another’s Coney Island.” In Hollywood she finds things even worse.

Now the Administration had invited Caroline herself to bully the movie business into creating ever more simplistic rationales of what she had come, privately, despite her French bias, to think of as the pointless war. Nevertheless, she was astonished that someone had actually gone to prison for making a film. Where was the much-worshipped Constitution in all of this? Or was it never more than a document to be used by the country’s rulers when it suited them and otherwise ignored?

She finds a new source of national power in the movies and begins to wonder if Hollywood might not even be able to persuade a defeated country that its army had been victorious, at least abroad.

A moving picture was, to begin with, a picture of something that had really happened. She had really clubbed a French actor with a wooden crucifix on a certain day and at a certain time and now there existed, presumably forever, a record of that stirring event. But Caroline Sanford was not the person millions of people had watched in that ruined French church. They had watched the fictitious Emma Traxler impersonate Madeleine Giroux, a Franco-American mother, as she picked up a crucifix that looked to be metal but was not and struck a French actor impersonating a German officer in a ruined French church that was actually a stage-set in Santa Monica. The audience knew, of course, that the story was made up as they knew that stage plays were imitations of life, but the fact that an entire story could so surround them as a moving picture did and so, literally, inhabit their dreams, both waking and sleeping, made for another reality parallel to the one they lived in…. Reality could now be entirely invented and history revised. Suddenly, she knew what God must have felt when he gazed upon chaos, with nothing but himself upon his mind.

She finds the war unpopular in California until the people succumb to every “anti-German, anti-Red, anti-negro demagogue,” and she resolves, when peace comes, to use the new power of the film to offset some of the damage done. Whether she will enjoy success in her project is far from clear at the end of her tale.

The parts of the novel that deal with the handsome and amiable Warren Harding and the gang of crooks with whom he is too easygoing not to associate are highly amusing, but on a lower level. They are like the play put on by the mechanicals in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, though considerably more ominous. Harding is shown as shrewd enough to see that if he is every delegation’s second choice he will be nominated in a convention deadlocked over bigger men. I suppose the reason his story lacks the impact of the two other themes of the novel is that here Vidal has little to bring to our already settled conviction of its sordidness. He adds a murder or so for zest, but it is not essential. We know those men would have been capable of anything. (Very incidentally, speaking of murder, Vidal’s solution of the famous one of the Hollywood director William Desmond Taylor has just been rebutted, at least so far as this reviewer’s jury is concerned, by Robert Giroux’s forth-coming study of the subject, A Deed of Death.* )

In Hollywood, as in many of Vidal’s novels (Lincoln and Julian excepted), the parts are greater than the whole. But that is what he would say of the universe. In a senseless mosaic are not the beautiful details all the more precious? His highly polished prose style, in part the fruit of his classical training, is a constant delight. One might even go so far as to call him a modern La Rochefoucauld. I suppose it is a mistake to take sentences out of context to illustrate this, but I submit a few.

The Irish lover of a society girl “had entered her life like a sudden high wind at a Newport picnic, and everything was in a state of disorder.”

Wilson, asked what was the worst thing about being president, replies: “All day long people tell you things that you already know, and you must act as if you were hearing their news for the first time.”

And here is the end of the court of Henry Adams:

In the twenty years that Caroline had known Adams, neither the beautiful room, with its small Adams-scale furniture nor its owner had much changed; only many of the occupants of the chairs were gone, either through death, like John and Clara Hay, joint builders of this double Romanesque palace in Lafayette Park, or through removal to Europe, like Lizzie Cameron, beloved by Adams, now in the high summer of her days, furiously courting young poets in the green spring of theirs.

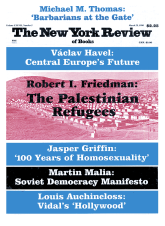

This Issue

March 29, 1990

-

*

To be published by Knopf in June.

↩