The United States of America is governed by its right wing and preached to by its left. Governors and preachers have a shared weakness for letting their imagination do the work better employed on trying to perceive the reality.

Thus, the left and right stand mutually assured that the United States is the sovereign power in a world where everything historically significant results from the will of our leaders.

That delusion seemed equally to govern the responses of those Americans who cheered and the fewer who deplored the electoral defeat of the Sandinistas, that most embarrassing of the successive reverses through which the Soviets and their comrade regimes have been tumbling since November.

The right is certain that “we”—i.e., the United States government—overthrew Daniel Ortega, and the left is just as sure that “they”—i.e. the United States government—overthrew Daniel Ortega.

But mightn’t it be more plausible to credit Ortega with his own disaster? The United States blackballed the Sandinistas with the international banks, enforced an economic boycott, and mounted a contra war of sorts against them. Still, grievous as these afflictions were, they cannot enough explain why, in a Nicaragua abounding with agrarian resources, the poor were worse fed after the revolution than before it.

Early in Ortega’s tenure, a woman active in the opposition Social Christian party wrote to caution him that “when you speak for and in the name of the people, I think you are referring to a people of your imagination.” That bewitchment, more than any work of his enemies, was his downfall.

He could not, after all, have called Sunday’s election and let it run as decently as he did unless he were still confident that he spoke “for and in the name of the people.” He exchanged the glasses of the not-unloveable fumbler for the contact lenses of the conquering male; he maintained the dominance of the media, the obscuring of facts with the flag, and the ladling out of patronage and souvenir gimcracks that are depressingly familiar in the campaigns of our own popular incumbents, and that are unappetizing in a rich country and obscene in one as poor as his.

The commendable dignity and resignation he has shown in defeat cannot altogether erase the image of the revolutionary who chose to play his final act as a political candidate barely distinguishable from any other, exulting in the size of his crowds and too stuffed with the fumes of imagination to wonder how many of them the press gangs of his retainers had rounded up for him.

The incompetence that the Sandinistas tried too late to repair had more to do with their catastrophe than the tyrannies that were so much exaggerated by our governors, who were as much distracted by a Nicaragua of their imagination as he was by his own. But then, far worse despots have taken it for granted that they were beloved.

For eight years, our National Security Council labored to devise and botch the execution of schemes to rescue the oppressed Nicaraguans that ran the whole range of the hare-brained, until we began to grow weary and all but resigned to living with the Sandinistas. And then Ortega made his last blunder, which was, like all his earlier ones, founded on the misconception that what he thought the Nicaraguans were was what they really were. And they threw him out.

There may be moments now when he wishes the wilder spirits in the Reagan administration had prevailed and the Marines been dispatched, and he was free of the mess of governing and back in the hills, a guerrilla once more and his spoiled copy book clean again.

For years, we planned and sometimes fought wars against the Soviets and their allies, voluntary and captive, and little good came of it all. And now, peaceful processes have been asserted and accomplished the transformation that was beyond reach by our belligerence.

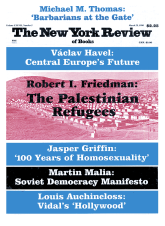

This Issue

March 29, 1990