Alice Munro (whose sixth collection of stories this is) amusingly suggests her approach to writing short fiction in the story “Differently”:

Georgia once took a creative-writing course, and what the instructor told her was: Too many things. Too many things going on at the same time; also too many people. Think, he told her. What is the important thing? What do you want us to pay attention to? Think.

Eventually she wrote a story that was about her grandfather killing chickens, and the instructor seemed pleased with it. Georgia herself thought that it was a fake. She made a long list of all the things that had been left out and handed it in as an appendix to the story….

The course was not a total loss, because Georgia and the instructor ended up living together. They still live together, in Ontario, on a farm. They sell raspberries, and run a small publishing business.

Alice Munro refuses to be bound by the rules—about time, place, and action—that a writing instructor might urge upon students. “Differently” moves, in a seemingly leisurely fashion, back and forth across many years to trace the story of Georgia, who was once married to a naval officer and has lived an apparently conventional life as a wife and young mother in a well-to-do Canadian suburb. There she becomes friends with a rich, childless, defiantly unconventional woman named Maya. “On the first level, they were friends as wives; on the second as themselves.”

As wives they listen dutifully to the school reminiscences of Ben and Raymond, the husbands. The deadpan narrator comments,

Ben and Raymond did not believe in leaving women out of the conversation. They believed that women were every bit as intelligent as men.

But “as themselves,” Georgia and Maya create fantasies about people they know—and confide their adulteries. Eventually Maya has an “accidental” one-night fling with Georgia’s motorcyclist lover. She begs Georgia’s forgiveness, but Georgia is implacable. The betrayal ends the friendship forever, and shortly afterward Georgia puts an end to her marriage to Ben as well.

“People [Georgia concludes] make momentous shifts, but not the changes they imagine.” Some fifteen years later, after Maya has died she sees Raymond again, and remarks that “we never behave as if we believed we were going to die.” He asks, How should they behave? ” ‘Differently,’ says Georgia. She puts a foolish stress on the word, meaning that her answer is so lame that she can offer it only as a joke.” Georgia’s answer reflects not so much a moral judgment as a bewilderment about the unruliness, the unpredictability, of life in a time when the traditional constraints have given way to an anarchy of impulse. How should she behave? There are no answers—not even dusty ones. A moment that she has experienced of “accidental clarity” leads nowhere, proves nothing.

The changes that occur year by year, the unexpected working out of personal destinies—themes more usually taken up in novels, appear again and again in the collection. The haunting title story, “Friend of My Youth,” begins with the narrator’s recurring dream about her dead mother, and the reader anticipates a story about the relations between a mother and her daughter. But the narrative shifts into an account of two farm women, sisters, who belong to a sternly puritanical sect called the Cameronians, and their relation to the dour man—engaged to one sister, seduced by the other—who helps run the farm; in subject and atmosphere, this material could almost have come out of a novel by Hardy. The account of the two sisters—especially of the older one, Flora, who is condemned to a life of self-denying spinsterhood—really belongs to the narrator’s mother. She had after all, as a young teacher in the community, boarded at the farm and known Flora well. But the daughter takes the story over in her own imagination, giving it a new, contemporary twist in which Flora emerges not as a stoically heroic figure but as a monster of sexual repression. By the end the reader realizes that the daughter’s relation to her mother—in all its ambivalence—has been central all along, even when the ostensible subject has been the odd events at the farm.

The restlessness of intelligent women forced to live in constricted or provincial surroundings is a recurring theme for Alice Munro, but she treats it ironically—even humorously. The dissatisfactions regularly lead them to adultery or to divorce. In “Wigtime” Anita, who has returned to her home town to nurse her dying mother, swaps stories with her old friend Margot, whom she has not seen for thirty years. Margot tells Anita how she used her husband’s infidelity to get him to buy the huge lake-front house in which she now lives. Anita, in turn, describes how a sudden attraction to a stranger in a restaurant led her to leave her husband.

Advertisement

“Then did you go and find that other man?” said Margot.

“No. It was one-sided. I couldn’t.”

“Somebody else, then?”

“And somebody else, and somebody else,” said Anita, smiling. The other night when she had been sitting beside her mother’s bed, waiting to give her mother an injection, she had thought about men, putting names one upon another as if to pass the time, just as you’d name great rivers of the world, or capital cities, or the children of Queen Victoria. She felt regret about some of them but no repentance. Warmth, in fact, spread from the tidy buildup. An accumulating satisfaction.

“Well, that’s one way,” said Margot staunchly. “But it seems weird to me. It does. I mean—I can’t see the use of it, if you don’t marry them.”

“An accumulating satisfaction”—the words could apply to Friend of My Youth itself. These stories are never too full—they give just enough. Alice Munro has mastered the art of what Henry James, using a spatial metaphor borrowed from painting, calls foreshortening—the art of creating an illusion of depth by bringing certain details forward for emphasis while allowing others to recede into the background.

Readers of William Trevor’s earlier story collections, six in all, will find in Family Sins, as before, that the Irish settings—mucky farms, shabby genteel boarding houses, schools, convents, hotel barrooms where more than a few drinks are taken—are coolly but sympathetically observed. So are his characters—foolish, blustering, guilty, touching in their various predicaments.

In “The Third Party,” Boland, who runs a small-town bakery, meets Lairdman, who is in the timber business, in the bar of Buswell’s Hotel in Dublin. Boland recognizes him as someone who had attended the same school and remembers that Lairdman had once had his head held down in a lavatory while his hair was scrubbed with a lavatory brush. But they have met for a reason that can only be humiliating to Boland: his wife Annabella and Lairdman have fallen in love, and Lairdman wants Boland to relinquish Annabella and, if possible, to give her a divorce. Boland, for whom the situation is no surprise, more or less agrees, but as he tosses back drink after drink of John Jameson’s (while Lairdman sticks to lemonade, which he is too stingy to pay for), he can’t help taunting his rival about the bullying episode at school. He also reveals something that Lairdman does not know and that Annabella would passionately deny: that she is unable to have children.

Trevor is particularly skillful in showing the mixture of slyness, abjection, and cruelty in Boland. Driving the fifty miles back home after having sobered up a bit, Boland broods over his wife’s longstanding unhappiness with him. ” ‘Poor Annabella,’ he said aloud…Poor girl, ever to have got herself married to the inheritor of a country-town bakery. Lucky, in all fairness, that cocky little Lairdman had turned up.” Then he realizes that he has effectively prevented Lairdman from taking Annabella away from him—and wonders why he has done it.

It hadn’t mattered reminding Lairdman of the ignominy he had suffered as a boy; it hadn’t mattered reminding him that she was a liar, or insulting him by calling him mean. All that abuse was conventional in the circumstances, an expected element in the man-to-man confrontation, the courage for it engendered by an intake of John Jameson. Yet something had impelled him to go further: little men like Lairdman always wanted children. “That’s a total lie,” she’d have said already on the telephone, and Lairdman would have soothed her. But soothing wasn’t going to be enough for either of them.

“Honeymoon in Tramore” takes us several steps down the social scale. Davy Toome, an orphaned farm worker, and his pregnant bride, Kitty, who is the daughter of the farm owners, have come to spend their honeymoon at a seaside boarding house, St. Agnes’s, run by a Mrs. Hurley. Kitty is pregnant by another man; she planned to have an abortion but lost her nerve in a fit of religious panic, and Davy, the poor orphan, saw his opportunity and asked Kitty to marry him. Trevor finely describes the details of high tea at the boarding house and the way in which the honeymooners spend their late afternoon in the drab resort, which offers as its leading attraction a motorcycle arena called the Wall of Death. That night Kitty, who has been brushing off Davy’s physical advances, drinks a great many bottles of stout and loudly boasts to the Hurleys about the heartbreak she has caused Coddy Donnegan, the probable father of her child, by marrying the lowly Davy; she even makes up another suitor, the cousin of the local priest. But Davy doesn’t mind. He doesn’t even mind when, back in their bedroom, she vomits and then passes out. We again are made aware of the complex mixture of detachment and sympathy Trevor brings to the revelation of a hardly admirable person’s inner life:

Advertisement

Davy stood up and slowly took his clothes off. He was lucky that she had gone with Coddy Donnegan because if she hadn’t she wouldn’t now be sleeping on their honeymoon bed. Once more he looked down into her face: for eighteen years she had seemed like a queen to him and now, miraculously, he had the right to kiss her…. Slowly he pulled the bedclothes up and turned the light out; then he lay beside her and caressed her in the darkness…. He had been known as her father’s hired man, but now he would be known as her husband. That was how people would refer to him, and in the end it wouldn’t matter when she talked about Coddy Donnegan, or lowered her voice to mention the priest’s cousin. It was natural that she should do so since she had gained less than he had from their marriage.

At least five of the stories in Family Sins confirm Trevor’s mastery. But the collection as a whole strikes me as a little tired, a little too reminiscent of situations and effects that we have encountered before. The work for the most part lacks the energy of the stories in Beyond the Pale (in my view Trevor’s strongest collection) or wonderfully sardonic vision that animates such early novels as The Old Boys or The Boarding House.

Ralph Lombreglia’s Men Under Water, his first published book—has received enthusiastic comments from John Barth, Amy Hempel, and Ann Beattie. One can see why, though Lombreglia writes a very different kind of fiction from theirs. There is nothing “postmodernist” or “minimalist” or “self-reflexive” (to use those tired expressions) in his approach. What Lombreglia’s somewhat disparate admirers are responding to is his extroverted good humor, his odd yet persuasive characters, the zany situations that he invents for them, his jazzy prose rhythms. Lombreglia can be a very funny man.

In the piece called “Inn Essence” the young narrator, Jeffrey, works as the salad man in an opulent New Jersey restaurant. He gets a message on his answering machine from the proprietor, Jimmy, who tells him that the pastry chef has gone mad again and has tried to kill one of the young Thai students whom Jimmy has hired to help out during the summer. Jeffrey must drive over at once. Wearing “pink Converse high-tops, wiped-out blue jeans, and a T-shirt with a cartoon of some happy snow peas dancing above the slogan BE A HUMAN BEAN,” Jeffrey sets out. But rather than face the situation, he is tempted to drive straight to the George Washington Bridge and New York:

Yes, I think to myself now, I could go for a day of hooky in Nueva York. The bookstores, the theatres, the streets full of people living lives of mysterious meaning. My foot wavers between the brake and the gas. But then I think of the thousands of restaurants in Manhattan, five or six of them on every block, and I almost lose control of the car.

At the restaurant, Jeffrey is plunged into a farcical tangle of events in which one might almost expect the Marx Brothers to show up. Immigration agents arrive, searching for the illegally employed Thai students:

I hurry out to the head of the corridor and stand behind the cigarette machines, scanning the dining room. Just inside the front door, next to the sign that says OUR HOSTESS WILL SEAT YOU, are two hard guys in rumpled suits. They look hungry, all right, but not for anything we serve here. They’re swiveling their heads on their big necks, checking the place out real good. Our hostess will seat you! For the first time in my career at Inn Essence I’d give anything to see Ethel [the hostess] walk around the corner—her face carved out of flesh-colored ice, her hair sprayed into a bronze battle helmet. She could make crème brûlée out of these guys.

Eventually Jeffrey, Ethel, the Thai students, and the now tied-up pastry chef find themselves locked in the pastry chef’s walk-in cooler while the immigration agents continue their search outside. The Thai students are punishing the pastry chef by gagging him with one of his own cream puffs and decorating him with squiggles of dark brown chocolate cream—“He looks like a gingerbread man in reverse, brown frosting on white.”

In the title story, “Men Under Water,” the narrator works as a handyman—fixing broken toilets—for Gunther, a gross and abusive hulk who owns a number of slum tenements but really wants to make movies and uses the narrator as a source of movie ideas:

Gunther is one of the largest people I’ve ever known, but it’s more than that, more than his general enormousness, the smooth expanse of his completely bald head, the perfect beardlessness of his broad face. Gunther has no eyebrows, no body hair whatsoever as far as I know; even the large nostrils of his great, wide nose are pink hairless tunnels running up into his skull. His velour pullover is open to his sternum, and the exposed chest is precisely the complexion of all the rest of him—the shrimplike color of new Play-Doh, the substance from which Gunther sometimes seems to be made.

The complications of the story defy summary, but they include an encounter with a menacing rock group called Acid Rain who live in one of Gunther’s broken-down houses, and a final episode in which the narrator experiences a kind of epiphany while scuba-diving with Gunther in his backyard pool.

Lombreglia’s comedy can be too broad, too farcical, and I am not sure how well it would stand up under a second reading. Yet, beneath its high-jinks, it is able to suggest not merely the crazed desperation of the characters but the weirdness and dislocations that dominate so much American life, public and private. William Trevor’s Ireland seems to belong to another century.

Lombreglia’s characters are classless and free-floating. They inhabit odd neighborhoods, ranging from college towns to trailer parks in California and run-down sections of Cleveland. They play jazz, team up with various women and separate, have their hearts broken and become manically inspired. They work as computer programmers, edit tapes, write video scripts…. Lombreglia’s mastery of software and communications jargon is put to wonderfully absurd effect. Even the message in a fortune cookie from a Chinese restaurant reads YOU WILL HAVE A LONG AND HAPPY FILE. Will Lombreglia develop into the S.J. Perelman of the high-tech scene?

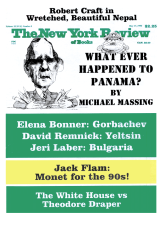

This Issue

May 17, 1990