In response to:

The Wound and the Bow from the March 1, 1990 issue

To the Editors:

Charles Rycroft, reviewing Leonard Shengold’s Soul Murder: The Effects of Childhood Abuse and Deprivation [NYR, March 1], notes that Shengold’s text omits mention of my book about Daniel Paul Schreber. Shengold’s book is at least the fourth work of his with Soul Murder in the title. The bibliography in his book refers to the second and third works, which were articles in psychoanalytic journals. However, it omits Shengold’s first use of the title. That was an article entitled “Soul Murder: A Review” (International Journal of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, August 1974). The review surveyed the history of the concept “soul murder,” but mainly criticized a book by me. The title of my book? Soul Murder!

Schreber (1842–1911) was an eminent German judge, who went mad at forty-two, and spent many years in mental asylums. He was a classic case of paranoia and schizophrenia and probably has been the most quoted patient in psychiatric history. Schreber called his condition “soul murder.” The term, he explained, referred to the idea “widespread in the folklore and poetry of all peoples that it is somehow possible to take possession of another person’s soul….”

Freud never met Schreber, but in 1911 wrote an analysis of him based on Schreber’s book Memoirs of My Nervous Illness. Freud concluded that Schreber’s paranoia had been a defense against homosexual love for his father, and that Schreber’s experiences of persecution by God were originally his own loving feelings for his father, now replaced by hatred and projected onto God.

In my Soul Murder I presented a hypothesis about Daniel Paul’s madness based upon the available evidence of his father’s methods of bringing up children.

Psychoanalytic authors largely ignored my views, at least in published writings. A theme of the Dutch sociologist Han Israëls (Schreber: Father and Son, International Universities Press, reviewed by Phyllis Grosskurth in NYR, January 18, 1990) was that, in so doing, the psychoanalytic community was condoning an infringement of the rules of scholarship. Yet Shengold, who twice cited Israël’s book in his own book, albeit only briefly, has infringed the rules of scholarship in just the same way. Despite using my title, Shengold’s Soul Murder ignored my Soul Murder (except in the bibliography)—though it discussed at length the case of Schreber!

How, then, to explain the psychoanalysts’ behavior? According to Rycroft, the reason, in Shengold’s case, “must” be that I am “an outsider, not a psychoanalyst, and, therefore, not a member of that elect group, the American (or should it be the New York?) psychoanalytic establishment, which probably makes up a large part of Shengold’s audience.” Yet Shengold mentions Israëls. Israëls is neither American nor a psychoanalyst, nor even a psychiatrist, whereas I am an American psychiatrist, educated and trained in New York City.

A more important reason, I think, for the exclusion of my views is that they are heretical. They are at direct variance with Freud. The word “heretical” is deliberate. I believe that from the start psychoanalysis has coped with dissent from Freud’s views in ways that have more in common with a religious movement than with a scientific or academic enterprise. Psychoanalysts have not considered what sort of evidence would be helpful in judging the likelihood that my views might be true—or false.

Rycroft has not “excommunicated” me, and confronts my views, but his thinking about them is muddled. According to Israëls, writes Rycroft, Schreber’s father “was not as famous and influential as both Schatzman and Freud had assumed, was not such a paragon as Freud had assumed or as vicious as Schatzman had painted him, and neither Freud’s nor Schatzman’s aetiological theories stand up to critical scrutiny.” That is all Rycroft says about the possible validity of the two theories. How famous and influential the father was is surely irrelevant to the question of whether he drove his son crazy. Israëls did not prove that the father was not as “vicious” as I had painted him, but even if Israëls had, that would also be irrelevant.

This is not to say that I am convinced that my theory is true. A prevalent view is that whatever schizophrenia is, it is probably a brain disorder. However, we still have little understanding of what schizophrenia is, or why anyone becomes schizophrenic. I expect that the answers will come from people who value a search for truth more than loyalty to doctrine.

Morton Schatzman

London, England

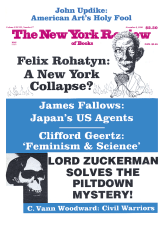

This Issue

November 8, 1990