The following was written before the Polish election in December. It first appeared in the Warsaw daily paper Gazeta Wyborcza, of which Adam Michnik is editor-in-chief.

This is a strictly personal reflection.

I feel obliged to publish it for the sake of all those who do not understand what has happened, and whose message of anxiety and solidarity has been reaching me over the last few months.

[Michnik refers here to the demand last spring by Lech Walesa, that Gazeta Wyborcza no longer use the Solidarnosc logo,

Solidarnosci

This demand was made after Gazeta Wyborcza failed to give full support to Walesa. Michnik and his fellow editors acceded to the demand after it was endorsed by the Solidarity National Committee in September.]

My primary feeling is one of embarrassment. The divorce within Solidarity was an ugly event. Instead of an open discussion of ideas, we got opaque insinuations and arguments about symbols.

The conflict over the Solidarnosc logo epitomized a more general disagreement concerning the shape of Polish public life, the kind of political culture we should adopt, and the future of our country. Principles, rather than details, were the issue, and the split within Solidarity became unavoidable. The process, which had started with the annexation of the right to use the Solidarnosc logo, ended with the transformation of union structures into vehicles for Lech Walesa’s election. One can hardly help feeling bitter about this.

The Solidarnosc logo is of great emotional value to people who were faithful to Solidarity for the last ten years, and who now find it difficult to part with it. These people printed the logo in underground pamphlets, scrawled it on city walls, and chanted the word in street demonstrations. Many Solidarnosc badges have been torn out of lapels and sweaters by the ZOMO riot police and the secret police, but people who wore them remained faithful to those familiar letters, despite persecution and prison sentences. For them, it meant the logo of hope and trust in a better, democratic, independent, and just Poland.

This logo has now been transformed by the majority of the Solidarity Trade Union’s leadership into an instrument of blackmail and a censor’s stamp. From now on, editors of all newspapers that display the logo in their masthead will know what articles they should avoid. When I realized this, I was relieved at my colleague’s decision to remove the slogan “There is no freedom without Solidarity” from Gazeta Wyborcza’s masthead. I feel no solidarity whatsoever with those who will turn a symbol of freedom and hope into a sign of opportunism and a tool for silencing people.

What was the charge against us? The resolution of Solidarity’s National Committee defined it all too clearly, we criticized Lech Walesa.

I may not have met all those who voted in favor of the resolution, but I pity them all. Impoverishment of the mind and spirit will always surface, sooner or later. I also congratulate Lech Walesa on such allies in his struggle for the Belvedere Palace [the president’s office]. He is getting what he asked for.

Campaigning at the Warsaw Steel-works, Walesa answered a question concerning the future of the newspapers that criticize him today: “Let them make these newspapers flourish,” he said, “and then you will come in and take them over.” The statement was later interpreted by Walesa’s press spokesman to mean: “Yes, democracy will take them over. New political forces will emerge from the election, and they will need their own press and media, which leaves them with one option: either they set up new ones, or take over the existing ones from those who have been politically defeated.”

I never expected Walesa and his spokesman to utter such a compact definition of the Bolshevik line of reasoning.

I have always openly admired Walesa’s political acumen. I truly respected his strategy during the difficult martial-law period. And I supported that strategy of persistence and common sense by being one of Walesa’s collaborators. His policy was both cautious and courageous. And, above all else, it was effective, and enriched by a remarkable instinct.

Our roads have since parted. We now represent diverse points of view. But I would still like to believe that an argument about ideas, rather than an exchange of insinuations, is possible between us. It would be very bad if what was once a friendship turned into venomous hatred.

Lech Walesa, my political opponent of today, is an outstanding politician. I believe that if you cannot pay due respect to your opponent, you will never be able to win respect for yourself.

I like many things about Walesa. I like his sense of humor, I admire his intuition and political savvy, and I admit that he played an outstanding role in our war with the Communist order. Therefore, it saddens me to see the chairman of the Solidarity Trade Union and Nobel Prize laureate waste the unique Polish opportunity, destroy his own good image and that of our country in the eyes of the world. It is painful for me to observe Walesa’s evolution from the symbol of Polish democracy to its present grotesque caricature. The decision to deprive Gazeta Wyborcza of the Solidarnosc logo for criticizing Walesa was the first shibboleth of what will happen to Polish democracy when these people reach for state power. It also summarized Walesa’s own concept of democracy.

Advertisement

Walesa wants to be president, and I do not blame him for this ambition. It worries me, however, that he wants to be an “axe-wielding” president who rules by decree and who likens democracy to a driver’s control over a car. “Now that we are changing the system, we need a president with an axe: a firm, shrewd, and simple man, who does not beat around the bush.” These are Walesa’s words. What worries me more than his words, however, is that he treats Solidarity as an instrument for the fulfillment of his own personal ambitions. It is also the confidence with which he announces that he will win at least 80 percent of the votes in the compulsory, open election that he demands. And his threats of a street revolt. It also worries me that he always speaks about himself, and never mentions his program. In conclusion: it worries me that Walesa will use any means to get into the Belvedere Palace.

As Solidarity chairman, he has proposed no program for the trade union in periods of austerity. During the last year, we have not heard a single word from Walesa on the union’s role or activity in the process of transition to a market economy, on methods for defending the interests of the working class, or on ways to deal with unemployment.

Instead, we have repeatedly been told that Solidarity had to split. Eventually, Walesa came and split it. He got rid of all those capable of opposing him and barring his way. In order to remove them, he considered it useful to describe them publicly as “eggheads” and “Jews.”

I can understand Lech Walesa’s motivation. His ambitions have not been fulfilled. Twice, he refused to compete for high political posts; he would not run for either house of the Parliament; nor did he attempt to become prime minister. In my opinion, he has always been driven by one motive: a certain vision of himself in public life. Walesa’s political ideal is that of a special place: ultimate power without responsibility. His concept of the presidency is to rule, and to defer all responsibility to the prime minister, the cabinet, and all the other government elite.

This concept is far from surprising: Walesa has always been a charismatic leader who would not respect a statute or a program, acting as if he did not understand the rules of democratic procedures. In August 1980, his ignorance was justified. Later, during martial law, Walesa decided that he did not need any understanding of those procedures. It may have been this decision, and his charisma, that made Walesa such a good leader during that period.

What is the nature of charismatic power? Charisma is the ability to control people’s emotions. Emotional subordination and the acknowledgment of a leader’s special abilities and talents create a special relationship between the leader and the ordinary man. The ordinary man’s blind trust in his leader makes him obedient. In the ordinary man’s opinion, the leader knows best what to do in any situation. The leader’s power is subject to no restrictions or regulations. His qualifications and competence become unimportant. So does the law. What becomes important are the random decisions of the charismatic leader.

This leader emerges from the void of a destroyed political stage, marked by the lack of, or the sudden surge of, hope; he is the result of a collective dream and of the desire for a new myth. He may be a prophet, a popular leader, or a street demagogue. He epitomizes the myth of the just, invincible leader. He evokes admiration and awe.

Charismatic authority is inherent in the most revolutionary historical processes: it helps to overcome fear and apathy, to destroy traditional order, and to overthrow old governments, whether monarchies or foreign occupations. Once victorious, this authority becomes domineering and antidemocratic; it towers above the people. Born out of collective hope for a free, dignified life, it leads toward a new dictatorship. The faith in the charismatic leader’s infallibility becomes the subject’s duty. The leader and his team demand that the faith be completed with voluntary acts of submission. A refusal to perform them is subsequently treated as a felony, a crime, and as high treason.

Advertisement

This is when a charismatic authority begins to wane. Such a leader, endowed with “divine grace,” proves unable to work wonders. But it is too late for the people to change anything: the leader has lost his charisma, but has kept the police. His team, chosen according to the principle of obedience rather than for professional qualifications, will not hesitate to use force to defend its power. The history of revolutions confirms this pattern, from Cromwell, through Lenin, down to Khomeini.

The myth of a charismatic leader collapses as soon as people lose faith in his supernatural power and denounce their own blind obedience. This history of revolutions teaches that the sooner the light dawns, the greater a nation’s chance to save its freedom and stability of order.

A victorious charismatic leader becomes pathologically jealous of his power and popularity. He also becomes suspicious, sensing enemies and plots all around him. In order to get rid of rivals, that is, of ordinary democratic mechanisms, he will promise anything to one and all, and he will not discuss political programs: he himself becomes his own program. He always talks about himself, his merits and congenial achievements, describing his plans in the most scant and general terms. He promises accelerations: fast improvement for everyone.

Lech Walesa will not be president of democratic Poland.

He may lose in the general presidential election. Judging by his boastful declarations, the Solidarity Trade Union chairman may have too little to offer, apart from himself and flood of contradictory promises. How does the “just division of Polish poverty” he promises agree with the demand he makes for “accelerated privatization?” Or the promised, instantaneous end to unemployment with the necessity to launch market mechanisms? And can [his] promise of doling out millions of zloty to individual people be taken seriously?

Walesa may also win the presidential election, but even if he does, he will not be president of a democratic Poland. Rather, he will become a destabilizing factor, creating chaos and isolating Poland from the rest of the world. Walesa said:

I do not favor classic concepts of the presidency, neither the French, the Italian, nor the American models. I will do it my way. I want to surprise everyone. My model is not wine drinking and dinners: it is a “flying Dutchman” who travels around the country and intervenes wherever necessary. There will be too much of Walesa, and this is why so many are afraid.

Walesa may win the election if he manages to maintain his image of “the father of the nation.” A father is free to get drunk and beat up his wife, but his children are not allowed to raise their voices or hands against him. If this myth paralyzes Polish minds and hearts, Walesa will win. He will win, even though he openly declares that he needs democracy only as a tool that allows him to grab the rudder of rule. I am afraid that once he grabs hold of it, all that will remain of democracy will be his own decrees.

Walesa’s merits and virtues are unquestionable: as a politician, he is wonderfully sensitive to public feelings and extremely gifted in the game of politics. Millions of people associate his name with the end of communism. However, this excellent politician apparently ignores the fact that the era of charismatic leaders is past. Today, charisma can only serve destruction.

Some features of Walesa’s character which made him a great leader of the several-million-strong Solidarity movement disqualify him as a president of a democratic state. Walesa is unpredictable. Walesa is irresponsible. He is incompetent. And he is also incapable of reform.

Walesa’s unpredictability was an asset in the struggle against totalitarian communism. But it spells disaster in the democratic structures of a modern state.

His irresponsibility was a by-product of opposition and underground activity: if you cannot influence the state, you take no responsibility for it.

Walesa cannot learn from his own errors because he is deeply convinced that he commits none.

Finally, Walesa’s opinions on the economy and foreign policy are paralyzing and horrific in their absurdity. Not only to Poles. Some foreigners who have met with him feel the same.

Lech was once a Polish and an international myth. The memory of the US Congress applauding the Solidarity leader is vivid in my mind. Walesa’s speech in front of Congress was an excellent, inspired lecture on the Polish effort toward freedom. He has destroyed this myth through his own appearances over the last few months.

A leader’s personality is his own business. Lech Walesa has always been egocentric, but we learned to live with it. But now, the situation has completely changed.

Walesa believes that whatever is good for him is also good for Poland. And for a time, I agreed with him. And for a time, it probably was true. But not any longer. Walesa’s presidential ambitions have had a catastrophic influence on Poland. He has introduced a new, brutal language into the public debate. Walesa said:

This is a scandal! This government will be brought to trial, I am saying it even now: it will be brought to trial for destroying documents, for helping the Communists make themselves comfortable, for robbing Poland—it must be prosecuted, and prosecuted it will be, in due time. Because it has failed in its duty.

This kind of language is a magnet for all those who are frustrated, who are driven by personal ambitions, and who lust after power. Toward his critics, Walesa adopts a patronizing, supercilious tone. He promises them that “Warsaw will be aired out.” He promises to become the springboard for truly Napoleonic careers. He has already started to distribute ministerial posts and other public offices Promises, promises. To each man according to his ambitions—Is this not the true meaning of Walesa’s “personal revolution?”

Lech Walesa—and I am saying this on the basis of a close personal acquaintance—has never been a populist or an anti-Semite. Populism and anti-Semitism were both idiotic doctrines to him. However, by preaching nonsense about “eggheads,” and by dividing people according to a racial criterion into Jews and non-Jews, he has appealed to followers of anti-intellectual populism and anti-Semitic phobias. These people will now support Walesa’s ascent to the presidency.

Walesa says: “I am a pure Pole, born here,” by which he implies that some other Poles are “not pure,” and were born elsewhere.

Criticizing some unfavorable opinion of the Western press, Walesa says that “some people’s tentacles reach far.” Doesn’t this lingo of obsessions and insinuations sound familiar?

Poland is not the only issue here. Poland is the most developed example of the process that we see in all post-communist countries. Democratic institutions are not deeply rooted, the economic situation is very difficult, great expectations have been aroused, and the procedures used for resolving conflicts have not been really tested. So stabilization is fragile.

The evolution from a totalitarian system to a democratic order is unprecedented and unprecedentedly painful. Great hopes generate enormous frustration. Many people do not understand that the reconstruction of a democratic state and a market economy must have its own consequence in the form of new work standards, new prices, and the bankruptcy of unprofitable businesses. The breakdown of the standards and ideas characteristic of the era of communism and anticommunist opposition has not been accompanied by the swift approval of new ideas, typical of democratic systems. The picture of the world becomes dim and shaky. This is the ideal time for demagogy. Demagogy that aggressively attacks the government may be successful, which must lead to destabilization. Destabilization in turn elicits chaos. Chaos generates a new poverty and a new dictatorship.

Make no mistake: all postcommunist countries will have to face this. Everywhere, in Russia and in Czechoslovakia, in Hungary and Romania, the phantoms from the past awaken: movements that combine populism, xenophobia, personality cults, and a vision of the world ruled by a conspiracy of Freemasons and Jews. A great danger to the democratic order comes from this direction.

We all must take care of democracy. This is what democracy’s success is based on in Portugal, Spain, Greece, and Chile. And it seemed to be the basis for the success of Poland’s democracy after the creation of Tadeusz Mazowiecki’s government. It seemed that all major political forces would unite in support—even critical support—of the government of national hope; that the period of this interim government, which would end with parliamentary and presidential elections, would be a time of compromise and concord. It was a condition and a chance for political and economic reforms, as well as for a new foreign policy.

The reality was different. Walesa broke up Solidarity’s camp, and declared “war on the top,” and that upset the internal compromise among Poles. A substantial debate was replaced by noisy rhetoric typical of an election campaign. Now, we face another choice: What kind of Poland do we want?

Observers from Western Europe and the US have adopted a wait-and-see policy toward postcommunist Europe. The initial euphoria has been replaced with concern. Where are these countries heading? Are the really returning to Europe, or to the old world of populistic dictatorships, intertribal conflicts, and permanent destabilization? The harm done by Walesa to the Polish cause through his utterances is based on this: on giving the impression of a country which is not stable, which is torn by constant conflicts.

I think—and I tell Western journalists—that this picture is false and simplistic; that the small, noisy, and aggressive minority is not typical of Poland. To prove that, however, it is not enough to repeat that Poles are by nature tolerant and are the victims of nasty slander coming from an internationally hatched plot. We must speak out loudly about this sick marginal group, we must oppose this syndrome of populism, authoritarianism, and xenophobia that produces terror.

What path do we wish to follow? Is it a path to the Europe of contemporary, democratic standards, or, on the contrary, a path of return to bygone traditions symbolized by authoritarian regimes, the hell of national conflicts, and extreme cases of religious intolerance? The position of Poles in Europe depends on the answer to this question.

I have given a good deal of thought to whether I should write this text. I must make the assumption that I will be misunderstood and that the meanest of intention will be ascribed to me.

I have the feeling, however, that I must not be silent any longer. Readers may claim that I am wrong, but I must be sure that I have written everything that I have come to believe by honest reasoning. This leads me to say that Lech Walesa’s presidency may be catastrophic for Poland. It may be the first case of a Peronist-type presidency in Central Europe, where only the shreds of a beautiful pennant, sacrificed to the absolute thirst for power by Solidarity’s leader, remain from the hopes for a national revival. If I had left this warning unstated, I would have felt like a participant in a lie dictated by my own personal comfort.

I do not attribute any ill will to Walesa. I do accuse him, however, of a complete lack of imagination and knowledge of a democratic state ruled by law. Walesa’s style of political action, which was his power during strikes and in the setting of covert activity, has become a dangerous trap in the era of building a democratic order. The same behavior that used to destabilize a totalitarian order must now lead to the destruction of the political culture of the young democracy. A charismatic leader will suppress all independent reactions with an appalling intuition, until he breaks the fragile Polish democracy.

We must listen very carefully to what Solidarity’s leader says today. We must listen to his threats and promises. Because, perhaps unintentionally, Lech Walesa clearly promises neglect of the law and democratic procedures, revenge on his political opponents, unprofessional ideas, and rule by incompetent people. I believe that television should show each one of Walesa’s public speeches several times, with no cuts. Everyone must know what he is choosing when he casts his vote in the presidential elections, so he will not be able to excuse himself later on with a lack of information.

Lech Walesa is a politician with a great talent for setting people at odds, and that is why he is so dangerous. His great merits will change into their opposites. They will become a curse for Poland. That is why I will not vote for Lech Walesa.

The expropriation of the Solidarnosc logo by Lech Walesa is a sign. A sign of the end of Solidarity. Solidarity used to be the essence of my life. I believed that the path to an independent Poland led through it. I would ask myself a single question: What is Poland going to be? And I would answer, in November 1980:

A self-governing, tolerant, colorful Poland, based on Christian values, and socially just. A Poland that is friendly toward its neighbors; a Poland, let us repeat this, that is able to compromise and act with restraint, to be realistic and loyal in partnership, but unable to tolerate slavery, unable to accept spiritual subordination. A Poland full of conflicts, which are natural for modern societies, but also full of the principle of solidarity. A Poland where intellectuals protect persecuted workers, and workers’ strikes demand freedom for the culture. A Poland that speaks of itself with pathos and derision; that has been conquered many times but never subdued, defeated many times but never crushed. A Poland that has regained its identity, its language, its face….

I believed that Solidarity, in spite of its internal differences, would be able to remain united in the name of all that was universal and essential. Today, I feel defeated.

The idea of Solidarity has entered its final stage. For its death Lech Walesa is responsible. I will remain a Solidarity man until the end of my days. But the logo that was with me for ten years I now lay beside my most personal mementos. Next to copies of court sentences, or the books I wrote in prison. I do not want to hide the pain I feel. I do not wish and have never wished, to support myself with the symbol that now stands for power and authority. I wore this emblem when it brought prison sentences, I do not want to wear it when it promises privilege. I sense this as a moment of trial—now we will find out what each of us is worth—without a symbol.

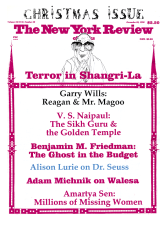

This Issue

December 20, 1990