1.

To awaken to history was to cease to live instinctively. It was to begin to see oneself and one’s group the way the outside world saw one; and it was to know a kind of rage. When I was there last year India was full of this rage. There had been a general awakening. But everyone awakened first to his own group or community; every group thought itself unique in its awakening; and every group sought to separate its rage from the rage of other groups.

Every day the newspapers carried plain official accounts of events in the Punjab: so many killed by Sikh terrorists; so many terrorists killed by police; so many “intruders” from across the Pakistan border killed.

In the wide streets and traffic circles of New Delhi there were reminders of the trouble in the north. At night there were roadblocks. At places below the trees there were sandbags, guns, and policemen. In some areas there was a policeman every hundred yards or so. In the city which the seventy-year-old publisher Vishwa Nath remembered as being empty and sleepy when he was a child (and where the trees would have been little more than saplings: still only a dream of a New Delhi) terrorism had led to the creation of this new and effective police apparatus.

The British forces that the London Times correspondent William Howard Russell had seen at the siege of Lucknow in 1857 had been made up principally of Scottish Highlanders and Sikhs. Less than ten years before, the Sikhs had been defeated by the sepoy army of the British. Now, during the Mutiny, the Sikhs—still living as instinctively as other Indians, still fighting the internal wars of India, with almost no idea of the foreign imperial order they were serving—were on the British side.

During the assault on Lucknow an incident took place that sickened Russell, who was a tough man, and a hardened relisher of war. One of the Lucknow palaces—the “yellow house” on the racecourse—was being attacked by Sikh soldiers. The defenders fought back with spirit; at one stage they shot and killed one of the Sikhs’ British officers. When it was clear that the defenders intended to fight to the end, the attacking soldiers were withdrawn, artillery was brought up, and the yellow house was blasted with shot and shell. The defenders were brave men, Russell said; they should have been sung in ballads. But no mercy was shown them in Lucknow. Those who had survived the shelling were bayoneted by the Sikhs and quickly killed—all but one man. For some reason this man was dragged out by the feet, bayoneted about the face and chest, and then placed on a fire. The tormented man struggled; half burnt, he managed to get up and tried to get away; but the Sikhs held him down in the fire with their bayonets until he was dead. Russell, in a footnote, said—a characteristic touch—that he saw the charred bones on the ground a few days later.

Russell was told that during the Punjab war the Sikhs mutilated all the prisoners they took. So this bayoneting and burning of the man who—possibly—had killed their officer might have been no more than their practice. Perhaps it was part of the barbarity of the country; or simply the barbarity of war. Russell loved war, but he had no illusions about it. “Conduct warfare on the most chivalrous principles,” he wrote, “there must ever be a touch of murder about it.”

In the Sikh fierceness at the battle of Lucknow there would have been a wish to get even with the “Pandies,” the Indian soldiers in the British army who had helped to defeat them less than ten years before. There would have been a more general wish as well to get even with the Muslims. And it was historically fitting that the Sikhs should have helped to bring about the extinction of Muslim power in Lucknow and Delhi, because it was out of the anguish caused by Muslim persecution of Hindus that the Sikh religion had arisen, in 1500—at about the time of Columbus’s last voyage to the New World.

People within the Hindu fold had always been rebelling against Brahmin orthodoxy, Vishwa Nath had said; and everyone who had rebelled had started a sect with its own rigidities. Buddha had rebelled; Guru Nanak (c. 1469–1539), the first guru of the Sikhs, had rebelled. Two thousand years separated the rebellions, and they had different causes. Buddha’s rebellion had been prompted by his meditation on the frailty of flesh. Guru Nanak’s rebellion or breaking away had been prompted by the horrors of the Muslim invasions—the horrors to which at that time no one could see an end.

Advertisement

Guru Nanak’s illumination was the quietist one that there was a middle way: that there was no Hindu and no Muslim, that there could be a blending of the faiths. Islam had its fixed articles of faith, however, its pervasive rules—no room there for Nanak-like speculation and compromise. The full Islamic “law” could be asserted at any time; and one hundred years later, at the time of the fifth Sikh guru, the persecutions and the martrydoms at the hands of the Moguls began. Nearly one hundred years after that, at the time of the tenth and last guru, Gobind Singh, the religion was given its final form, and the Sikhs were given their distinctive appearance: the hair not to be cut, and to be wrapped in a turban, a kind of underpants to be worn, and a steel bracelet, and a knife—so that every day, with these intimate emblems, a man would be reminded of what he was.

As the Mogul power declined in the first half of the eighteenth century the power and numbers of the Sikhs grew. In the ravaged north of India, in the interim between the collapse of the Moguls and the coming of the British, there was for a short time the Sikh kingdom of Ranjit Singh. This was the kingdom that the British defeated with the help of “Pandy” in 1849. But there was no great humiliation with that defeat; it might even be said that that defeat propelled the Sikhs forward.

The British, at the height of their empire, had a general disregard for all Indians. Even in 1858, while the mutiny was going on, Russell noted this slighting British attitude toward the Sikh soldiers who were fighting on the British side. But by being incorporated into British India the Sikhs were immeasurably the gainers. They were granted a century of development. Without the British connection, northwest India—assuming that there had been no more regional or religious wars—might have been no more than Iran until oil, or Afghanistan: poor, despotically ruled, intellectually disadvantaged, fifty or sixty or more years behind the rest of the world.

Independence and the partition of India in 1947 damaged the Sikhs; millions had to leave Pakistan. But again, as after their defeat by the British, they quickly recovered. With the expanding economy of an industrializing independent India, with a vast country where they could exercise their talents, the Sikhs did very well; they did better than they had ever done. They became the country’s best-off large group; they were among the leaders in every field. And then in the late 1970s their politics, always sectarian and clannish and cantankerous, became confounded with a Sikh fundamentalism preached by a young man of simple background, a man born in the year of partition. There began then the train of events which were to lead to the daily budget of terrorist news in the newspapers; and the khaki-clad policemen with guns in the green streets of New Delhi.

For 150 years or more Hindu India—responding to the New Learning that had come to it with the British—had known reforming movements. For 150 years there had been a remarkable series of leaders and teachers and wise men, exceeded by no country in Asia. It had been part of India’s slow adjustment to the outside world; and it had led to its intellectual liveliness in the late twentieth century: a free press, a constitution, a concern for law and institutions, ideas of morality, good behavior, and intellectual responsibility quite separate from the requirements of religion. With a group as small as the Sikhs, where distinctiveness of dress and appearance was important, there couldn’t be this internal intellectual life; even the idea of such a life wasn’t possible. The religion had reached its final form with the tenth guru, and he had declared the line of gurus over. Such a religion couldn’t be reformed; reform would destroy it. A new teacher could only restate its fixed laws and seek to revive old fervor. So it happened that India’s most advanced group could be called back by a village teacher to a simpler past.

The preacher’s name was Bhindranwale, after the name of his village. His first name was Jarnail; this was said to be a corruption of the English word “general.” At his first appearance he was encouraged by the congress politicians in Delhi, who wished to use him to undo their rivals in the Punjab state. This seemed to have given him a taste for political power. The word used most often—by admirer and critic—for Bhindranwale in this incarnation is “monster.” The holy man became a monster. He moved into—effectively occupied—the Golden Temple of Amritsar, the Sikhs’ holiest shrine, built by the fifth guru (who was more or less Shakespeare’s contemporary). He fortified the Temple, making use of its immunity as a sacred place; and, with a medieval idea of the scale of things, perhaps a villager’s idea of a village feud, he declared war on the state. To serve Bhindranwale and the faith, men now went out with the mission of killing Hindus. They stopped buses and killed the people in them. Riding pillion on motor scooters, they gunned down people in the streets. The resulting shock and grief would have confirmed the terrorists in their idea of power, would have confirmed them in their fantasy that it was open only to them to act, and that—as in some fairy tale—an enchantment lay over everyone else, rendering them passive.

Advertisement

Eventually the Indian army assaulted the Temple. They found it better fortified than they knew. The action lasted a night and a day; Bhindranwale was killed; and there were many casualties, among soldiers, defenders, and Temple pilgrims. Hindus as well as Sikhs grieved for the violation of the holy place; Hindus also offered prayers there. Police officials were later to show that there was another, cleaner way of isolating the Temple. But at the time, to deal with a novel situation—a murderous insurrection conducted from the sanctuary of a holy place—the army action, heavy-handed though it was, seemed to many people to be the only way.

The damage was done. Stage by stage, then, the tragedy unfolded. To avenge the desecration, Mrs. Gandhi was murdered by some of her Sikh bodyguards. And, again, it is as though the men who planned the murder didn’t sufficiently understand that their action would have consequences, that by doing what they did they would be putting their community at risk: Sikhs were settled all over India. There were riots after the murder. The most dreadful were in Delhi, where hundreds died. Out of that great fire in 1984, the terrorist incidents in the Punjab, on the frontier with Pakistan, were the embers.

To most people what had happened in the Punjab was a pure tragedy, and not easy to understand. From the outside, it seemed that the Sikhs had brought this tragedy on themselves, manufacturing grievances out of their great success in independent India. It was as if there was some intellectual or emotional flaw in the community, as if in their fast, unbroken rise over the last century there had developed a lack of balance between their material achievement and their internal life, so that, though in one way so adventurous and forward looking, in another way they remained close to their tribal and country origins.

2.

The establishing of a Sikh identity was a recurring Sikh need. Religion was the basis of this identity; religion provided the emotional charge. But that also meant that the Sikh cause had been entrusted to people who were not representative of the Sikh achievement, were a generation or so behind.

Bhindranwale had spent most of his life in a seminary in the country town of Mehta Chowk, not far from Amritsar. At the entrance to the town there were small shops set in bare earth yards on both sides of the road. One shop had this sign: UNIVERSIL EMPLOYMENT BEURO Overseas Employment Consultant. All around were fields of ripe dwarf wheat, due to be harvested in a few days. There were also fields of mustard, and fields of a bright green succulent plant grown as animal fodder. Lines of eucalyptus marked the boundaries between fields, adding green verticals to the very flat land: line standing against eucalyptus line all the way to the horizon suggested woodland in places.

Fields went right up to the seminary. The flat land, spreading to the horizon below a high sky, seemed limitless; but every square foot of agricultural earth was precious. The gurdwara, or temple attached to the seminary, had white walls, and the Mogul-style dome that Sikh gurdwaras have, speaking of the origin of the organized faith in Mogul times. The dome looked rhetorical; it stressed the ordinariness of the Indian concrete block which it crowned. The window frames of the white block were picked out in blue. The main hall of the gurdwara was quite plain, with bigbladed ceiling fans, and a wide-railed upper gallery. Colored panes of glass in the doorways were the only consciously pretty touch.

The seminary building was just as plain. On the upper floor, in a concrete room bare except for two beds, the man who was the chief preacher talked to the visitors. There were no more guns at the seminary, he said; and they took in only children now. Some of those children, boys, came to the room, to look. They wore the blue seminarian’s gown that went down to mid-shin. It was bright outside, warm; the gowned and silent small boys in the bare room, come to look at the visitors, made one think of the boredom of childhood, of very long, empty days. Some idea of sanctuary and refuge also came to one. Many of these children were from other Indian states; some—solitaries, wanderers—seemed to have been converted to Sikhism, and to have found brotherhood and shelter in the seminary. That idea of welcome and security was added to when a big blue-gowned boy brought in a jug of warm milk and served it to the visitors in aluminum bowls.

The chief preacher said he had come to the seminary when he was about the age of the boys in the room. He had left his family home to stay in the seminary: that was more than twenty years ago.

It was in some such fashion that Bhindranwale had come to the seminary. He had come when he was four or five. Twenty-five years later he had become head of the seminary; and five years after that—after he had taken on the heretics among the Sikhs—he had moved to the Golden Temple. There, two years later, he had died.

He was from a farming family, one of nine sons, and he had been sent to the seminary because his family couldn’t support all their children. What could he have known of the world? What idea would he have had of towns or buildings or the state? In these village roads, which ran between the rich fields, there were low, dusty, red-brick buildings, with rough extensions attached, sometimes with walls of mud, sometimes with coverings of thatch on crooked tree-branch poles. Straw dried on house roofs. Shops stood in open dirt yards.

After twenty-five years in the seminary, Bhindranwale began to call people back to the true way, the pure way. He would go out preaching; he became known. One man heard him preach in 1977—a year before his great fame—in the town of Gayanagar in Rajasthan. Three thousand people, perhaps five thousand, had come to hear the young preacher from Mehta Chowk, and Bhindranwale spoke to them for about forty-five minutes. “He held them spellbound, talking the common man’s language.” What was said? “He asked people not to drink. He said ‘Drinking does you harm, and you feel guilty. Everybody wants to be like his father. Every Sikh’s father is Guru Gobind Singh. So a Sikh should wear long hair, and have no vices.’ There were many references to the scriptures.”

In this faith, when the world became too much for men, the religion of the tenth guru, Guru Gobind Singh, the religion of gesture and symbol, came more easily than the philosophy and poetry of the first guru. It was easier to go back to the formal baptismal faith of Guru Gobind Singh, to all the things that separated the believer from the rest of the world. Religion became the identification with the sufferings and persecution of the later gurus: the call to battle.

The faith needed constantly to be revived, and there had been fundamentalist or revivalist preachers before Bhindranwale. One such was Randhir Singh. The movement he had started in the 1920s was still important, still had a following, could still send men to war against heretics and the enemy. The head of the movement now was Ram Singh, a small dark man of seventy-two, who had been a squadron leader in the air force.

He said of the founder of his movement, “He saw the light. His skin was dark, but when he saw the light he started glowing. He could see the future and also all the things about the past. His skin glowed more than English people’s. He had rosy cheeks—the light emanated from his cheeks. He saw the light when he was twenty-six. He revolted against the British government. This was the Lahore conspiracy case of 1920. He was imprisoned for life.

“In the jail one day a padre asked him, ‘You look healthy. You must have good food.’ Sant Randhir Singh said to the padre, ‘I have the worst food.’ The padre said, ‘You look happy. Do you have someone with you or do you stay alone?’ The sant said, ‘I’m never alone.’ The jailer said to the padre, ‘The man is telling lies. We never put two prisoners together.’ So the padre asked the sant again, ‘Who stays with you?’ And the sant said, ‘Almighty.’

“When the sant came out in the 1930s—after sixteen years in prison—he began to devote his life to singing religious verses, and reading, and administering amrit to others.” (To be baptized a Sikh is to “take amrit,” nectar.)

I asked the squadron leader, Ram Singh, “Why is the amrit necessary?”

He said, “God is hidden within us. He is a name only—in every human being. When you take amrit, only then you become of it—that name comes automatically on your tongue.”

He started on a discourse about amrit. “It’s a mixture of pure water and white sugar. The sugar is created out of white sugar and baking soda. It’s heated, so that it swells and foams up, so that, solidified, it forms sugar buns. It is mixed with the water in iron containers, and an iron double-edged sword is moved backward and forward in the mixture. This was initiated by the tenth guru, Guru Gobind Singh. You give amrit to render the receiver deathless. Iron is a magnetic metal. In that iron vessel in which you mix the amrit you have the greatest concentration of lines of magnetic forces. When a conductor moves across the line of magnetic forces you get an electromagnetic force. That energizes the sugar buns and water, and to a small extent dissolves the iron in it. So it’s a little iron tonic as well.”

We were talking in his sitting room. There was a carpet on the floor, and a cloth on the center table, and knick-knacks on hanging shelves: a clock, a small statue of a rearing horse, a china jar, a color snapshot of a child, a small silver salver (a souvenir of London), and some small painted flower pieces.

Squadron Leader Ram Singh was born in 1916. His father was a farmer, and he had gone to some trouble to give his son an education. Ram Singh joined the air force in British times, in 1939. In 1957 he had taken amrit.

Why had he felt the need? Had there been some personal crisis? He said no. He had read books by Sant Randhir Singh, and had discovered that without amrit one just couldn’t reach God.

He spoke clearly. I felt he wished to be friendly. He had the tone and manner of a reasonable man, a man at peace.

He was in a fawn-colored costume, with a milk-chocolate-colored cardigan. He wore what looked to me like a head-tie rather than a full turban; it was of a saffron color. The knife, one of the five emblems of Sikhism, hung in a sheath from a big black cross-band, and it made him look less like a warrior than a bus conductor. His beard was a yellowish grey.

The movement aimed at creating pure Sikhs, and amrit was necessary. “After you take amrit, you don’t eat food not cooked by amritdharis,” people who have taken amrit. “That helps to control the five evils: lust, anger, covetousness, ego, family attachments.”

It would also have created the idea of brotherhood. Was that why some people in the movement had become suspect to the government?

He said they had had trouble with a reformist Sikh group who believed in living gurus: they believed, that is, that the line of gurus didn’t end with the death of the tenth guru in 1708. They were a small group, but they were a great and constant irritant. In 1978 one person from his movement had been killed by people from that group, and some people of the movement had gone underground.

But he spoke as one for whom violence was far away. His life was consumed by his faith. He got up—his day began—at midnight. He had a bath, and said his prayers till four. From four till 5:30 he read from the Sikh scriptures. Then he slept until 8:30. That was his life. That was the life that had come to him with the pure faith he had turned to when he was forty-one. It clearly had given him peace.

Just before we left, his son came in. He was a handsome, light-eyed man. He had overcome polio, and was a doctor. He was sweet-visaged; he radiated gentleness; he had all his father’s serenity. He was in government service; he said with a smile that they were currently on strike. The silver salver on the hanging shelf, the souvenir of London, was something he had brought back after a trip to England.

3.

The Golden Temple was at Amritsar, the pool of nectar. It was said that there had been a pool here known to the first guru. Sacred sites usually have a history: it was also said that the place was mentioned in a version of the Ramayana, and that two thousand years and more before Guru Nanak, the Buddha had recognized the special atmosphere of the Golden Temple site. The emperor Akbar, the great Mogul, gave the site to the fourth guru, and the first temple was begun by the fifth guru in 1589, the year after the Spanish Armada. In the chaos of the eighteenth century the temple suffered much from the Muslims. The Sikh king Ranjit Singh rebuilt it in the nineteenth century. He gave the central temple its gold leaf dome. This gold leaf, reflected in the artificial lake, has a magical effect. Even after the battle marks of recent years the Temple feels serene.

Bhindranwale came to the sanctuary of the Golden Temple in 1982, and he turned it into his fortress and domain. He was thirty-five. Four years before, he had been only a preacher and the head of a Sikh seminary; now he was a politician and a warrior. He was also an outlaw; pursuing a vendetta against the Nirankari sect, whom he considered heretics, he had been accused of murder.

He was a proponent of the pure faith; he was persecuted; he offered his followers a fight on behalf of the faith. He incarnated as many of the Sikh virtues as any one man could possess. He and his followers controlled the Temple. The guns were smuggled in from Pakistan. From the Temple, killings were planned, and bombings, and bank robberies. Not all of these things were done with Bhindranwale’s knowledge; there would have been a number of freelance actions: the seeds of chaos were right there. The Temple provided sanctuary; it was the safe house. It was not physically isolated from the town; the old town went right up to its walls. Guns and men could come and go without trouble.

In that atmosphere some of the good and poetic concepts of Sikhism were twisted. One such idea was the idea of seva, or service. When terror became an expression of faith, the idea of seva was altered.

Now, five years after the assault on the temple, the terrorists lived only for murder: the idea of the enemy and the traitor, grudge and complaint, were like a complete expression of their faith. Violent deaths could be predicted for most of them: the police were not idle or unskilled. But while they were free they lived hectically, going out to kill again and again. Every day there were seven or eight killings, most of them mere items in the official report printed two days later. Only exceptional events were reported in detail.

Such an event was the killing by a gang, in half an hour, of six members of a family in a village about ten miles away from Mehta Chowk. The two elder sons of the family had been killed, the father and the mother, the grandmother, and a cousin. All the people killed were devout, amritdhari Sikhs. The eldest son, the principal target of the gang, had been an associate of Bhindranwale. But a note left by the gang, in the room where four of the killings had taken place—the note bloodstained when it was found—said that the killers belonged to the “Bhindranwale Tiger Force.”

The North Indian village tends to be a huddle of narrow angular lanes between blank or pierced house walls. Jaspal village, where the killings had taken place, was more open, simpler in plan, built on either side of a straight main street or lane. It was a village of eighty houses, and was a spillover from a neighboring, larger village. Eight years before, some of the better-off people of that village had begun to build their farmhouses at Jaspal, on big, rectangular plots on either side of the main lane.

When we arrived, in mid-afternoon, the people at work in the edge of the village were cautious. We—strangers arriving in an ordinary-looking hired car—could have been anything, police or terrorists: two different kinds of trouble. They frowned a little harder at their tasks, and pretended almost not to see us. It was strange to find that there was no policeman or official in the village, and that less than forty-eight hours after the murders the village had been left to itself again.

The central lane was wide and paved with brick, and it was strung across with overhead electric lines. The farmhouse walls on either side were flat and low, some of plain brick, some plastered and painted pink or yellow. In an open space below a big tree there were short poles or stakes for tethering buffaloes, and there was a high mound of gathered-up, dried buffalo manure. At various places down the lane—as though the lane also served as a buffalo pen for some of the villagers—there were flat, empty, propped-up carts with rubber tires, and buffaloes and feeding troughs and heaps or pyramids of dung cakes for fuel. The village ended where the bricked lane ended. Beyond the lane—half in afternoon shadow now, and dusty where not freshly dunged—there was a narrower dirt path, sunstruck, with very bright fields of mustard and ripe wheat, tall eucalyptus trees with their pale green hanging leaves, and crooked electricity poles.

We didn’t have to ask where the house of death was. About fifteen women with covered heads were sitting on a spread in the wide gateway. The gateway was painted peppermint green, with diamonds of different colors down the pillars. The two big metal-framed gates had been pulled back: wrought-iron pattern in the upper part, corrugated iron sheets fastened to the criss-crossed metal frame on the lower part, the resulting triangles painted yellow and white and blue and picked out in red. At the far end of the farmyard—the vertical leaves of the young eucalyptus trees hardly casting a shadow—the men sat in the open on the ground, white-turbaned most of them, their shoes taken off and scattered about them, a string bed nearby. The buffaloes were in their stalls, against the low brick wall, over which the gang had jumped two nights before. Such protection at the front, metal and corrugated iron; such openness at the back, next to the fields.

We were taken to the farmhouse next door. It seemed a much richer place. The yard was not of beaten earth, but paved with brick, like the lane. It was one of the few houses in Jaspal to have an upper story. This upper story was above the entrance. It was decorated with a stepped pattern of black, white, green, and yellow tiles, and at the corners there was a regular pattern of half-projecting bricks, for the style. The trailer in the courtyard was to be attached to a tractor: it carried the mysterious, celebratory words that all Indian motor trucks have at the back: OK TATA. And there was something like a flower garden in one corner of the courtyard: sunflowers, bougainvillea, nasturtiums, plants that loved the light.

We sat on string beds in the open, bright room at the left of the entrance. The brick ceiling, which was also the floor of the upper room, rested on wooden beams laid on steel joists. The concrete pillars were chamfered, with bands of molded or carved decoration, and painted in many colors—an echo here of the pillars of Hindu temples before the Muslim invasions. Everything in this courtyard spoke of the owner’s delight in his property.

People began to come to us. They sat on the string beds, their backs to the light, or leaned against the painted pillars. The Punjabi costume—elegant in Delhi and elsewhere, was here still only farm people’s clothes, the smeared and dirty clothes of people whose lives were bound up with their cattle. A sturdy woman in her thirties, in a gray-green flowered suit, grimy at the ankles, came with a child on her hip and sat on the string bed. The woman’s eyes were swollen, almost closed, with crying.

The child who now sat on her lap and held on to her was the seven-year-old son of the eldest brother. The boy had been in the room when his father was killed; he had been saved from the burst of the AK-47 only because another brother had hidden with him under a cot. The boy was still dazed, still able from time to time to take an interest in the strangers; occasionally, while people talked, tears appeared in his eyes. He had been put into a clean, pale brown suit, and his hair had been done up in a topknot.

The uncle who had saved him was a handsome, slender man of twenty-three. He had dressed with some care for this occasion, all the visitors coming: a blue turban, a stylish black and gray checked shirt. He began to tell of the events; while he spoke, a girl cousin came and unaffectedly rested her head on his shoulder.

The farming day went on. The buffaloes came home, through the front gateway. The heavy chains they dragged rang dully on the bricked yard, and their hooves made a hollow, drumming sound. And village courtesies were not forgotten: water was brought out for the visitors, and then tea.

Joga was the name of the man in the black and gray checked shirt. What he said was translated for me then by the journalists with me, and amplified the following day by Avinash Singh, a correspondent of the Hindustan Times.

The family had had dinner, Joga said, and a number of them were in the room on the living quarters side of the courtyard. (The opposite side was for the cattle or buffaloes.) Some of them were “sipping tea.” A little after nine there was a commotion in the courtyard, and someone called out from there: “The one who has come from Jodhpur, and poses as a religious man—he should come out.”

Joga thought at first that some villagers were calling, but then the tone of the voices convinced him that they were “the boys,” “the Singhs.” “The Singhs”: the word here wasn’t simply another word for Sikhs. It meant Sikhs who were true to their baptismal vows; and in these villages it had grown to mean men from one or other of the terrorist gangs. “Singhs” was the word Joga used most often for the men who had come that night. The other word he used was atwadi, “terrorists.” Only once did he say munde, “the boys.”

Joga was holding Buta’s son on his lap. As soon as he decided that the men who had come were Singhs, he hid with the child below the cot.

Buta, the eldest brother, went to the door of the room. The men outside had called for the man who had come “from Jodhpur.” Jodhpur had a meaning: Buta, with two or three hundred others, had been detained in the fort at Jodhpur as a suspected terrorist for more than four years, from June 1984 to September 1988—just eight months before. Buta had been detained because he had been in the Golden Temple at the time of the army action, and he was known as a religious follower of Bhindranwale. Buta admitted being a follower; but he said he wasn’t a terrorist. He was in the Golden Temple that day, he said, because he taken an offering of milk for the anniversary of the martyrdom of the fifth guru, executed on the orders of the Emperor Jahangir in 1606.

This was the man, only thirty-two, but already with many years of suffering, his life already corrupted, who went and stood at the door and looked out at the many muffled men in the courtyard. The leader said, “Who is Buta Singh?”

“I am Buta Singh.”

“Come with us. We want you. We have come to take you.” And the man who spoke said to one of his Singhs, “Tie his hands.”

Some of the men made as if to seize him by the arms. Buta said, “I won’t, I won’t.” There was a scuffle, and two of the Singhs fired. A bullet hit Buta just below his ribs on the right side, and he fell backward into the room. Buta’s mother threw herself on her son, saying to the man, “Please don’t kill.” Buta’s brother Jarnail and Buta’s wife, Balwinder, also fell on Buta. The Singhs pulled away Balwinder by her hair from her husband, and they fired again with their AK-47s. Buta hadn’t been killed yet; but he was killed now, with his mother and brother. Buta’s grandmother was wounded, and was to die in a few days.

Buta’s father ran out from his room at the front of the courtyard, on the street side. He ran across the courtyard to where the men with the guns were. He tried to grab one of the guns. He was killed with a shot to the head.

After this, the Singhs—there were eight or nine of them—went out of the gateway to the main village lane. Opposite, a little to the right, was the house of Natha Singh, Buta’s uncle, the first cousin of his father. They wanted Natha Singh. When the front gate of Natha’s house wasn’t opened for them, they went around to the back, climbed over the low wall, and they called for him. Natha had five children; the eldest was a polio-stricken girl of fourteen.

Natha came out when he was called. The gang took him out to the lane, and asked him to take them in his tractor to the house of Baldev. They very much wanted Baldev as well. They had a case against him: Baldev, they said, was an amritdhari Sikh, but Baldev had gone against his vows and had been having dealings with a temple priest in the town of Jalandhar. They didn’t find Baldev when they got to his house, which was just at the end of the lane, next to the fields. Baldev had heard the gunfire and had slipped away; he had had threatening letters before because of his religious practices. So they had driven back in the tractor with Natha, and in the lane, just outside his house, they had shot Natha Singh dead.

The Singhs had been in the village for half an hour, not more. Then they were gone. It wasn’t until eight hours later, at about 5:30 in the morning, that someone of the family picked up the note the terrorists had left behind—now bloodstained and hard to read. The note said that Buta Singh and Natha Singh had been killed because they had been responsible for the deaths two months before of two terrorists just half a kilometer from the village. There was a price of 30,000 rupees on the head of one of the terrorists killed then.

The police said that the gang in question wanted Buta to join them. Buta, as a man who had been close to Bhindranwale until 1984, would have given the group some “credibility.”

There was another story as well that the villagers told. Shortly after his release from Jodhpur, Buta—who had taken a BA degree while in detention—had applied for a minibus permit. This was part of the government’s plan to rehabilitate people like Buta. Buta went one day to the town of Jalandhar to see about his permit. He didn’t come home at the time he should have done. People in the village made inquiries, and they found that Buta had been arrested by the Central Reserve Police Force in Jalandhar. He was held for nine days.

Buta never told anyone what he had been arrested for, or what had happened during the nine days of his detention. All they knew was that Buta was very frightened when he came back, and never wanted to be alone when he went out of the village—to the tubewell or the local market.

We went at last next door, to the house of death, picking our way past the women sitting in the gateway. They were not keening now; they were sitting as silent as the men in the sunstruck yard—no shade there from the vertical eucalyptus leaves, the afternoon sun seeming in fact to catch the leaves in a kind of glitter. The plastered courtyard wall of the living quarters was painted pink, the pierced ventilation concrete blocks above doorways and windows were peppermint green, like the entrance walls: Mediterranean colors. The doors and windows and the vertical iron bars over the windows were a darker green.

The bedrooms were at the front of the building, on either side of the gateway. The doors opened into the courtyard, and the back wall (with ironbarredwindows) was also the wall of the lane. There were two rooms on the left. In addition to being used as bedrooms, Avinash told me, they would have been used as storerooms, with wheat and rice in gunny sacks. Buta Singh’s father had been sleeping in the room at the corner of the courtyard: it was from there that he had run out.

The bedroom to the right of the gateway was the principal room of the farmhouse. It was where Buta Singh and his wife slept. It was also the drawing room. There were no chairs now. The chairs and the center table, Avinash said, had been removed, because it was known that after the murders visitors were going to come. There were two beds side by side. The bedclothes on them were in disorder. There was an extra bed in the room, together with tin trunks and chests. There was a souvenir of the Golden Temple on a shelf, and Sikh religious calendars on the wall. In Sikh popular art the gurus are shown with the pupils of their eyes half disappearing below the upper lid, so that more white than usual is seen in the eyeball; this way of rendering the eyes suggests blindness and an inner enlightenment. In this room the pictures made an unusual impression.

There was a photograph of Buta’s father-in-law, and there was one other photograph, of Buta himself: a studious-looking young man in glasses. The studiousness and the glasses were a surprise, in this setting of the farmhouse and the village. Buta might have cultivated the scholarly appearance; he would almost certainly have been the first man in his family to have received higher education. Buta’s wife, Balwinder, was the only graduate in the village; and no doubt it was her example that had made Buta study for a BA degree while he had been in detention in Jodhpur.

Two or three generations—not only of work, but also of political encouragement, political security, development in agriculture, the growth of a national economy—had led Buta’s family to where it had got. Two or three generations had led to the beginning of an intellectual inclination in Buta Singh. Awakening to knowledge, he would have seen with a special clarity what he had come from. Ideas of injustice and wrongness would have come more easily to him than ideas of the steady movement of the generations; and the fundamentalism of someone like Bhindranwale would have seemed to answer every emotional need, would have appeared like a program: ennobling complaint and the idea of persecution, offering history as an idea of glory betrayed, and offering for the present the twin themes of the enemy and redemption. That idea had trapped him and swept him away.

The police said he had been killed because he had refused to join the gang. The note left by the Singhs said he had been responsible for the deaths, by police bullets, of two important terrorists. There might have been truth in both statements. It was part of the wretchedness of the situation, where men had to be blooded into the cause, and once blooded, couldn’t turn away. He must have suffered. Everyone said that he was a very religious man. He had bought religious primers for his two young sons; he went twice a day to the gurdwara to pray. Such devoutness! In the beginning it might have met an emotional and intellectual need; later, perhaps, it had become just a praying for protection.

It had ended for him in the next room. The room was at the side of the courtyard. It faced south. The door was open; but, against the pale glare of the dung-plastered courtyard and the sunlit pink-distempered wall, the doorway looked very dark. Inside, in the shadows, brass pots and steel pots glinted on shelves. There were scuff marks on the floor where Buta and his family had fallen. Not more than forty-two hours had passed since then. But the marks might have been made by the people who had come to look. The note left by the killers, when it was found, was soaked in blood. The ground now was black with flies, barely moving.

Only three days before the killing, Avinash told me later, Buta Singh’s wife, the graduate, had opened an English-medium school in the neighboring village. It was something she had wanted to do for a long time. “I thought my dream had come true,” she told Avinash. “I didn’t know my husband’s return from Jodhpur would spell doom for the family.”

Across the lane was the house of Natha Singh, Buta’s uncle. His wife couldn’t read. She had five children, the eldest with a disability. She told Avinash, “I don’t know what to do My world is finished.”

It was for Natha Singh that a new spasm of mourning began when we went outside. To the right of the peppermint-green entrance with the multicolored diamond pattern, women were now sitting, now throwing themselves down on the spot where Natha had been killed. when he had driven the tractor back from Baldev’s house. On both sides of the dung-dropped lane farming life went on: buffaloes held their heads down to the troughs at the side of the lane, against the walls of houses. Taking out these animals, bringing them back, milking them or unyoking them, feeding them, bedding them down—these things gave rhythm and correctness to a day and were followed like religion.

Two other men from the village had been detained in Jodhpur. While the women keened, and the buffaloes ate, we heard one man’s story. On the very day Ranjit was released from Jodhpur. his brother was killed. Ranjit didn’t say who his brother had been killed by; this suggested that his brother had been killed by “the boys.” His brother’s body was found twenty kilometers away from Amritsar—not far from where we were. And so it happened that on the day Ranjit returned home, after four and a half years in Jodhpur, his brother’s body also came home. That happened just a month before.

How could they talk so calmly of grief? They had to some extent been prepared by the faith; but they could talk like that because many hundreds had suffered like them. Avinash said that he and other correspondents had seen more than fifty mass killings such as we had heard about that afternoon. Exactly a year and a week before, eighteen members of a Rajasthani clan, half of whom were Sikhs, had ben killed. The AK-47 was a weapon of pure murder. It could empty a magazine of thirty-two bullets in two and a half seconds; the bullets sprayed out at many angles, and could kill everyone in a room in those two and a half seconds. In one night in one subdivision of Amritsar twenty-six people had been killed, including a thirty-day-old baby and the ninety-one-year-old head of a family.

We drove back to Amritsar through byways and village ways, looking at the rich, well-cultivated land. It was still afternoon and bright, still safe. After some time we felt we had lost our way. We were on a dirt road between irrigated fields. We saw two men on a bicycle, one man doing the pedaling, one man on the carrier. The man on the carrier was sitting elegantly, sideways, feet together, but not dangling or hanging down. His shoes were locked together and they were lifted, as though above the dust. When we stopped to ask the way, he slid off, with a practiced movement, and offered to come with us, to set us on the road to Amritsar.

He was as handsome as his posture on the bicycle had suggested. He was a Sikh, with a trimmed beard. The trimmed beard had a meaning: it meant he had not taken amrit. He had heard about Buta Singh’s death, and the other murders, and he thought it dreadful. He himself didn’t belong to any of the purely Sikh political groups. He was in business in a small way and he considered himself successful. He enjoyed his success. He had built a house, he said, with toilets and flush system and everything. He had spent four lakhs on this house, £16,000. But he was thinking now that he might have to give up his house and leave the area. He hadn’t taken amrit, and he didn’t intend to. He didn’t think he would be able to live by the strict amritdhari rules, and he didn’t want to get into trouble with the boys, as other people had done.

4.

Dalip, a reporter, told of what happened after the Golden Temple had been occupied by Bhindranwale.

“People stopped going to the Golden Temple. Both my neighbors stopped going, though they wanted to. People were angry about what was happening in the Temple, but the Sikh political party never condemned the desecration of the Temple by Bhindranwale and his guns. The Sikh political party were fighting a joint agitation with Bhindranwale from the Golden Temple, and they were afraid of him. He was a killer. He didn’t worry about Hindu or Sikh—once you opposed him, you would be on his hit list.

“I was witness to one killing he ordered. I was sitting in Room 47 on the third floor of the Guru Nanak Niwas. This was one of the rest houses in the Temple where he used to stay with his followers. There were armed men sitting all around, eight, ten people. This was in the middle of 1983. Suddenly one guy entered. He was a middle-aged Sikh, in shirt and pyjamas, and he was looking glum. His hair was cut and his beard was cut awkwardly. He started talking to Bhindranwale: ‘Santji, this is what Bichu Ram, a police inspector, has done to me. He took me to a police station and desecrated me. He cut my hair and my beard.’

“Bhindranwale immediately asked one of his aides to take down all the details. Fifteen days or so later this Bichu Ram, in charge of one of the police stations, was shot dead.

“The second way of operating, or ordering killings, was to pronounce the names of people whom he wanted killed from a public platform. He did this from the 19th of July, 1982, till June 1984. He would make a speech. Always against Mrs. Gandhi, Giani Zail Singh [the Indian president], and Darbara Singh, the chief minister of Punjab. And he would say these people should be taught a lesson for having harmed the Sikhs. Afterwards he would talk against some local police officers. And many of the people whose names he spoke would be later killed. Bachan Singh, a senior police officer of Amritsar, was killed, together with his wife and daughter.

“I used to talk to Sikhs. But by and large Sikhs did not come forward to condemn the happenings in the Golden Temple. They were blaming New Delhi—everything was being done by New Delhi. They were never criticizing Bhindranwale and his men. Whenever terrorists were killed the Sikhs were very upset—they spoke of fake encounters. Whenever the terrorists killed innocent people, I never heard my neighbors expressing regret.”

Dalip had Sikh connections; this explained some of his passion.

I said, “Someone who knows Sikhs well has told me that there was something wrong with the way Bhindranwale and his followers looked. They had the eyes of disturbed people. Was it a kind of communal madness, you think?”

“It’s the minority fear, the persecution complex, the death wish. It’s a new religion. It has produced great generals and great sportsmen. But it hasn’t produced great religious thinkers to strengthen the religion. Nothing happened after Guru Gobind Singh set up the Khalsa in 1699. Since 1699 it has produced no great thinkers.

“It’s madness, it’s fanaticism. It can’t really be explained. It’s the tragedy of the Sikh religion that in the post-independence era a man like Bhindranwale has come to be accepted as the most important Sikh leader since Guru Gobind Singh. He was called in his lifetime by many Sikhs the eleventh guru. And he really was a product of Mrs. Gandhi. She built him up to fight the Sikh party, the Akalis.”

“Why did educated people give their support to Bhindranwale?”

“Frustration.”

“When did you first see him yourself?”

“The 24th of July, 1982. In the Golden Temple. The famous Room 47. I was checked by his bodyguard. Guns in the Temple were seen for the first time in 1982, and it’s a perversion of the religion.

“He arrived in the Golden Temple on the 20th of July, 1982. He left it dead on the 6th of June, 1984. He harmed the Sikhs the most, the Sikh religion the most. He harmed Punjab, and he harmed India.

“The aides questioned me, and when I told them I was a journalist, they smiled and were very happy, and they immediately escorted me inside.

“I greeted him. He was sitting on a string bed, and he was nicely dressed up, wearing that long white cotton gown going down to his knees, and that blue turban. And his revolver hung from a belt around his waist. He had angry eyes—you asked about the eyes. He looked lean and hungry, the type of people who are dangerous. He said, ‘Who are you?’ Very dictatorial. I said, ‘I’m a journalist.’ I gave him the name of the weekly I worked for, and I mentioned that I was also the correspondent for a Canadian paper. ‘Do you want to interview me?’ ‘No, I’ve just come for your darshan.”‘

Darshan is what a holy man offers when he shows himself: the devotee gets his blessing merely from the sight, the darshan, of the holy man.

“He was very flattered. He smiled and he laughed. He had been very serious when I entered.

“I found an old lady handing over to him bundles of currency notes, and she also removed one or two of her gold rings and handed them over to him. Standing over the old lady was an old man, who I learnt later was General Shabeg Singh.” Major General Shabeg Singh: cashiered in his mid-fifties for embezzlement, and now acting as Bhindranwale’s military adviser.

“Shabeg was lean and thin, middle height, very fair, wearing spectacles, flowing beard, white beard, white pyjama and kurta. He was smiling. I shook hands with him. He said, ‘I’m General Shabeg Singh. I led the Mukti Bahini in the Bangladesh war.’ I said, ‘Sir, you are a general. How did you get attached to Bhindranwale?’ I needed copy for a color story—my first day in Amritsar. His reply was, ‘I see spirituality in his eyes. He is like Guru Gobind Singh.’

“I came out of the Golden Temple a sad man, wondering about the fate of the community, wondering about the general’s reply, comparing Bhindranwale with Guru Gobind Singh. I was very sad when I sat at the typewriter. Because I was not impressed by Bhindranwale. I knew he was not Guru Gobind Singh. I knew he was just being used by the Indira Congress to harm the rival Akali party in Punjab. He was an ordinary man on whom greatness was being imposed. Why should the community accept him? Why should General Shabeg Singh not judge him as a man? Why were people just impressed by his angry looks and the armed men around him? He was not an intellectual, not a thinker, and he was not a pious man.”

Dalip meant, I suppose, that Bhindranwale wasn’t really a man of God. But what were the noticeable religious aspects of the man? There must have been many.

“He was a vegetarian, a lover of music. He would go to the Golden Temple water tank every morning at three and listen to the music played by the blind musicians from inside the main shrine. They play on the harmonium and recite the scriptures. That music is soothing, divine—and I give him full marks for wanting to be part of that. You feel the presence of God when that music is played in the silence, and there are no people around. He did that every morning for one hour. And he was not a womanizer.”

The vegetarianism, the love of music, the early rising, the sexual control, were run together in this account to give an idea of the austerity of the man that so impressed people in the early days, when he went out preaching and urged people to be like their father, the guru.

Dalip said, “He made himself a monster.” Monster: it was the word people used of the later man. “He began to think he would rule the country or rule Khalistan. He wanted to rule something. He accepted the compliment when people told him he was like Guru Gobind Singh. Subconsciously, Bhindranwale began imagining himself to be Guru Gobind Singh—a reincarnation of the tenth guru.

“I will give you two more pictures of him. The first is from the middle of 1983. A colleague on an Indian daily did a big story saying that Naxalites* had entered Bhindranwale’s camp. I checked out my colleague’s story and found it all right, and I extended it with inquiries from my own sources. Bhindranwale hated the story in the daily, but I learned about that only later. The day after my own story came out, I went to see Bhindranwale. That was my practice, to go and see him after things about him by me were printed.

“The same room in the temple. Room 47. Now I can open the door and go in coolly—everybody knows me now. I took along a friend with me, someone from the medical college. The moment I open the door of Room 47, I see the angriest look in his bloodshot eyes. They were red eyes when he was angry, which often he was. And I got the message. There were eight or nine of his armed admirers in the room, and two journalists were interviewing him.

“He started shouting at me, in crude Punjabi, at the top of his voice: ‘How dare you compare me with thieves and scoundrels and lumpens?’ That is what he thought Naxalites were. He continued shouting at me in this way for three minutes, and then he ordered one of his men to bring the copy of the magazine with my story. And I, the magazine’s correspondent, stood in front of him like a schoolchild who has offended the teacher. I couldn’t utter a word—I was so afraid: I could see the guns around, and I knew he could kill me if he wanted to.

“The magazine arrived. He handed it to me. He had cooled down a bit, but he was still very angry. He asked me to translate what I had written into Punjabi. I pleaded that I wasn’t good at translating from English into Punjabi. He cooled down more. And then, to my amazement—I realized how shrewd he was—he signaled to me, while he was sitting on his string bed—I was no more than four feet away—to come closer to him.

“He wanted me to come closer to him, and when I went closer to him on his string bed, he pulled my head down and he whispered into my ears. ‘You are like a younger brother to me,’ he said in Punjabi, whispering, ‘and still you write against me.’

“The meeting ended, and I came out of the room with my friend, the man from the medical college. He had wanted to see Bhindranwale, and had asked me to take him, because as a journalist I could go in and out of Room 47. I apologized to my friend for the shock treatment.

“I didn’t meet Bhindranwale for a couple of days after that. I felt most uncomfortable. I didn’t know how to report him. I knew one had to be critical of him, but it was so difficult to be sitting in Amritsar and to attack him. For a few months I kept quiet.

“But the magazine wanted stories, and in October 1983 I did a story saying that Bhindranwale was losing his popularity, that not many people were coming to see him. The magazine played it up: “The Sant in Isolation,” a full two pages, with a big photograph of that big man in his white cotton gown, half smiling, half frowning. And, as usual, after my story appeared, I went to see him.

“He was having a walk on the terrace of the rest house, the Guru Nanak Niwas. Not many people were there—forty, fifty, mostly his followers. He started walking with me. Obviously he didn’t know about the story. That was the last time I had a friendly chat with him. The next day I went again to see him, accompanying a Canadian TV team as an interpreter. He had learnt about the story by then, and in full public view, on the same terrace of the Guru Nanak Niwas, where he had walked with me alone the day before, he told me that if I didn’t stop writing against him, then I wouldn’t be alive. He said this in Punjabi, in symbolic language. Sannu uppar charana anda hai. ‘We know how to take you up.’

“After this I stopped seeing Bhindranwale. I didn’t report on him. I didn’t do any critical story. I was afraid. On the 23rd of December, 1983, he shifted from the Guru Nanak Niwas to the Akal Takht, from the rest house to a sacred building. I went with some local journalists to see him. He was sitting on the floor—fifty, sixty people with him. Some fruits and sweets lying nearby. He gave me a piece of sweet and a banana, and he made some sarcastic remark, which I don’t recall. Obviously he didn’t like me any more. Some weeks later a colleague was stabbed outside the Temple. This didn’t have anything to do with Bhindranwale, but in the atmosphere of fear nobody went to the aid of the stabbed man. They just stood and watched him bleed. I asked my paper to move me somewhere else.”

I felt that Dalip, talking of the morning music in the Golden Temple, had spoken with a special reverence for the sacredness of the old site. I asked how shocking Operation Bluestar, the army action at the Temple, had been to him.

“Bluestar itself was not shocking to me. What was shocking was the manner in which it was done. It was a very bad operation. I thought Bhindranwale and his men could have been caught easily without bloodshed. I felt sorry for the ninety-three soldiers who were killed. They chose such a bad day to catch Bhindranwale. And they didn’t even catch him.”

He was killed on June 6; and General Shabeg was killed. Many other people with him managed to leave the Temple before the army action. They lived.

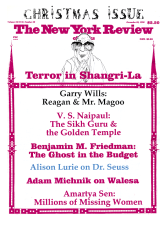

This Issue

December 20, 1990

-

*

Editors’ note: The Naxalites are, or were, a group of left-wing extremists, originally from West Bengal, whose program called for forcibly taking over land for landless famers; they have carried out violent actions in various parts of India.

↩