1.

The autumn of 1990 seemed to promise improvement in the Soviet political climate, and a transition to new kinds of economic relations appeared at last to be under way. Today we have to realize that this transitional stage consists of two processes that are at once interrelated and independent. The first is the transition from empire to a commonwealth of independent states, and the second is the transition from a centralized, planned economy to a market economy and private enterprise.

For the first time in five years this autumn we saw the start of a concrete program for dealing with our growing difficulties. The economic program of the economist Stanislav Shatalin—albeit controversial in many respects, including some of its basic premises—offered the Supreme Soviet a chance to deal radically with economic problems by setting a five-hundred-day timetable for making fundamental changes in much of the economy. The agreement in late August between Gorbachev and Yeltsin was also an encouraging event. It was perceived as an agreement between the central government and the republics, primarily the Russian federation of which Yeltsin is president. Without such an agreement no further progress is possible in principle.

But no less important was the possibility that the potential dialogue between Gorbachev and Yeltsin could become the start of a center-left coalition. That the agreement between Gorbachev and Yeltsin could be seen as a symbolic manifestation of the potential cooperation between the left and the center is very important from my point of view, since I believe such cooperation is absolutely necessary if we are to surmount our enormous problems. The agreement between Gorbachev and Yeltsin also seemed to pose an obstacle to both chaos and authoritarian rule.

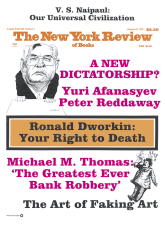

However, these glimpses of fragile hope for our society were blurred by intense new conflicts, which by the end of November ended in a presidential act that I can call by no other name than a step toward dictatorship.

How did this new development come about? In September and October our politics had taken another turn, toward a sharp conservative reaction. I attribute this to the attempt to exert strong pressure on Gorbachev. And there is no contradiction here with what I have said elsewhere—that Gorbachev himself was conservative enough not to be threatened by the pressure of conservative forces from outside his own circle. It is otherwise very difficult to explain both his rejection of the Shatalin program in late October—the only plausible program in the present circumstances—and his attempts to combine the Shatalin plan, for which he himself had a marked preference, with the government program sponsored by Nikolai Ryzhkov, which was altogether incompatible with Shatalin’s program.

At the same time, the coalition of conservative and reactionary forces has been gathering strength. I mean the Party apparat, the KGB, the military-industrial complex, and the generals. There were threatening troop movements in the fall—that is perfectly clear now. The confusion and bewilderment the generals displayed when they spoke earlier this year at the Supreme Soviet against depoliticizing the army were replaced in November by a clear and implacable voice expressing the firm positions of the army leadership. Colonel V. Alksnis accused the popular movements in the five Soviet republics of collaborating with the CIA. The Russian Communist party made several similarly aggressive statements. This was evidence that these forces were not in the least pleased with a radical turn in the direction of a market economy.

However, in first supporting the Shatalin plan Gorbachev was overriding the conservative government plan sponsored by Ryzhkov. The economic and social conflict in our country is thus visible in the political divisions among the top leadership. In putting aside the Shatalin plan Gorbachev capitulated yet again to the conservative forces of the country.

The obvious unsoundness of the government program, perhaps not evident to everyone at first, was left in no doubt after the government presented different versions of it three times to the Supreme Soviet, and to the people, and failed to convince them. In these circumstances an ethical and civilized government would have been forced to resign. A good question is: Why can’t the president accept this inarguable fact?

I think that beyond the great many events that could have influenced the president in his capitulation to conservative forces there is something else, something very substantial. I see at least two reasons for his “retreat” at the height of an acute crisis, and after the Russian Republic had already voted to carry out the Shatalin plan.

First, if the present government is disbanded and resigns, the next government will not be formed constitutionally, since the Supreme Soviet will not be able to create a new government. Many of the republics, apparently including the Federation of the Russian Republic (RSFSR), will avoid taking part in forming such a government. Under these conditions, unconstitutional measures would have to be taken to form a cabinet or committee under the president. And that would inevitably call into question the very existence of the Supreme Soviet of the country—a Supreme Soviet unable to form a government would be an anomaly—and therefore also of the Congress and of the presidency. This is the first reason why Gorbachev does not face reality and admit the glaring inadequacy of the present executive branch to deal with the present historical moment. Yet the government remains in place.

Advertisement

Another reason may be even more important: if a new government or a new cabinet were organized to carry out economic reform, it would have to call attention to the mistakes that have been made during the last five years of perestroika. It would have to do so if only to distance itself from the unfortunate experience of the previous government.

The mistakes and the scale of the collapse in which we now find ourselves have not yet been fully revealed. Many statistics are still hidden, and the most vital information has been sealed away. We know that our gold and diamond reserves are being sold. But to what extent? Yeltsin rebuked the president for such sales but his statement did not elicit any constructive information in response.

We all know that we have backed regimes in, say, Iraq, Cuba, Angola, and so on; but just what our government has done to prop them up during the last five years and to support them financially is still hidden in the bureaucratic morass.

We speak about the deformations in our economy and the colossal distortions created by the military-industrial complex, but we don’t know exactly what that monstrous complex consists of. We have no statistics on the proportion of the gross national product that it consumes, nor do we know how many people are employed by it, or what it has been doing during the last five years. To this day we still do not know the extent of the weakness of the industries that are supposed to provide the necessities of life—food, light industry, and so on. We have to guess.

All these questions demand answers. The experience of Eastern Europe reveals that its people are prepared to demand answers and to seek reparations from those who created the harsh conditions in their countries. I am not in favor of bloodshed or of new acts of repression in the name of “justice.” But it is important to realize that an awakened popular consciousness, which is equally capable of being just or being extremist, may turn out to be dangerous both to the authorities and to society. Our government, in my view, has become panicky, afraid to stand before the people and reveal what it has done during the last five years. A new executive could reveal all this; and a wave of popular wrath could then sweep away not only Ryzhkov but Gorbachev as well. That is the second reason for Gorbachev’s strong defense of the present, ineffectual government.

We do not have an elected executive branch. The Supreme Soviet and the Congress of People’s Deputies do not reflect the moods and tendencies of today’s society and therefore do not adequately represent society. No clear distinction of functions exists among the government, the president, the presidium of the Supreme Soviet, the Presidential Council, and so on. Executive power cannot be exercised through a clear line of vertical authority. As a result, presidential action is inadequate—almost all presidential decrees (except for the decree permitting investments) rescind or replace the resolutions of the Council of Ministers, the executive branch. Incompetent resolutions and decrees therefore subvert one another at all levels of government and the result is the paralysis of the executive power and chaos. The functional disequilibrium of the entire social system is pushing it toward a free fall, a state of entropy, in which elemental forces naturally grow more powerful. I am worried not so much by the president’s mistakes or indecisiveness as by the functional inability of society to move forward within the present power structure, especially during what we hope will be the current transition to a fundamentally new economy—the essential component of any new system.

The requirements of this transitional stage need to be formulated legally. Unless we have specific deadlines and administrative mechanisms to carry out a transition we will remain stuck in our current condition of self-destructive drift. I believe we must go beyond this and move toward both a new constitution and a new agency to coordinate relations with, and among, the republics and to try to bring about agreement among them.

Executive power on the Union level has obviously exhausted itself in its current form. Strictly speaking, a Union Council of Ministers is not necessary. Much more needed is an entirely new and flexible body that would function as a center, or committee—what it is called is not the point—to coordinate a strategy for establishing horizontal ties among the republics. Or it could be a committee drawn from the various republics themselves that would coordinate their policies. In any case such a committee should carry out only the functions that are delegated to it by the republics (or other units, if any are formed). If one were to conceive an optimistic sequence of events, such an agency could become the basis for a possible government based on agreement among the republics.

Advertisement

And here we can begin to see the logic behind the contradictions that face us.

The only way out of the difficulties we are in is through the joint efforts of all the republics. The economy of the Soviet Union can be compared to an enormous factory and the regions and republics as different shops within that factory. Such an economy can function only in more or less coordinated rhythms. It is not suited, unfortunately, to independent, autonomous actions. Gigantic regions are incapable of functioning alone—Kazakhstan has basically been turned into a source of raw materials and Uzbekistan, an enormous republic with a large population, is hostage to its cotton monoculture and is unable to exist independently. In effect, over 80 percent of the production of the Ukraine is put to use by the central government, especially its energy, coal, and so on. This situation prevails everywhere, and we still only know about it superficially. If we are shown what has been concealed, it will be clear how many of the connections between people and their regional economic resources have been broken, and what the real situation is in entire regions and branches of industry.

So we really should work together, but the national and state policy for the last seventy years (not the only source of our troubles and contradictions; their roots must be traced back to the fifteenth century when Ivan III conceived the ambition that Moscow be a third Rome) has made the component nations of the empire so angry and so intolerant that it is impossible for them to act together. The forced leveling of the republics, the flattening out of different civilizations with their particular world views, mores, and religions—wholly ignoring the content of whole cultures and civilizations—produced rivers of blood, the arbitrary division of land, and the loss of freedom. Borders were set up wherever it suited the state.

Lenin was no exception, despite our totemic passion for seeing him as a flawless leader. He never gave the nationalities issue the attention it deserved even though he said, I believe, that he was very much to blame for not having the time to deal with it. That did not stop him from regarding the question of nationalities as secondary. What counted more for him was realizing socialism; and in order to do so, he and his colleagues had to pacify the many nations and ethnic groups that were in no hurry to embrace the new, redemptive social life that the revolutionary leaders offered them. Therefore the revolutionaries did not mind giving half of Armenia to Turkey and half of Azerbaijan to Iran; they assumed that the world revolution, which for some reason was reluctant to give itself over to Bolshevism, would eventually set things straight. Nagorno-Karabakh and other regions were merely instruments for a policy that never proved its validity. Today it is clear that it is this policy that must bear the weight of historical guilt.

Then came the Stalinist horrors, when entire nations were punished and moved, once again their borders were redrawn. Now we must take this crazy-quilt empire, with all of its territories bathed in blood, as the basis for solving longstanding economic questions. Not only do the component nations of the USSR reject the idea of fraternal friendship and a unified Soviet Union; the very idea of a treaty establishing a new union has lost or is rapidly losing its attraction for them. This is the first contradiction—the issues facing us can be solved only through cooperation among the republics, but for reasons with deep historical roots that cooperation is impossible.

The second contradiction is that while we must move to a market system—hardly anyone argues against this now—the transition to the market is taking place in an economy that is permeated by the military-industrial complex. After stormy disputes over the facts, no one can say what percent of GNP comes from the military-industrial complex. That it still has a monopoly on this kind of information is an answer of sorts. During World War II the military budget amounted to between eleven and twenty-five kopeks of every ruble. Today, in peacetime, the president tells us that the military budget makes up 18 to 20 percent of the whole, while several economists say it amounts to as much as two thirds. The juxtaposition of peacetime and wartime budgets is itself instructive.

The recent statistics on the military expenditures in 1989—they were hurriedly published last November—not only fail to clarify this issue but make it even more mysterious, since the figures released omit the most important information: the figures on strategic forces, because “in the USSR they are not clearly organized,” those on the export of Soviet arms, by country and region, and those on the cost of supplies for reserve forces, and more.

The military-industrial complex greatly distorts our entire economic life. More than half of all the machinery produced in the USSR is made for the military-industrial complex. According to the economist Yu. Yaremenko, more than 65 percent of all production is for military purposes. Only 5 percent of military products are for long-term use, that is, are among those products whose number per capita serves as a measure of a country’s well-being. This figure of 5 percent allows us a glimpse of the hidden economic war the military-industrial complex wages against the national economy.

Shifting this economy to a market system, even by following the Shatalin plan, will be very difficult. Many parts of the economy—such as food processing and light industry, as well as agriculture—simply will not be able to function in a market economy. If they had to work in a real market these enterprises would not be able to pay for raw materials or energy and would have to stop production. The second contradiction therefore is no less dangerous than the first: we cannot move to a market system while maintaining centralized methods of management based on administrative command—but we cannot overcome the military-industrial complex without using those centralized methods.

For a start we must put an end to the monopoly on information about the military-industrial complex, its physical size and financial cost, and the number of its employees. Then we must decide among ourselves how to overcome the contradictions I have described. In a world that has changed fundamentally, where capitalism is no longer pitted against communism, and where communism has ceased being the alternative for the rest of civilization, we retain a strangely archaic attitude for all our seeming interest in the modern. Notwithstanding the radical changes that have taken place in the international situation, our society is still thoroughly militarized. Apparently some people in authority still want to show the world, if not in words then by a display of force, that capitalism is coming to an end. And the guarantee that it will do so is our glorious military establishment with its atomic, biological, and other weapons.

The way out of this situation lies in a radical change in both the domestic and the foreign policies of the Soviet Union, a change that I think could come about through a national agreement involving all the republics to dispose of the military-industrial complex (of course not in the absurd sense of asking missile engineers to make sewing machines, however useful such products may be). The military-industrial complex must be ended, but not in a barbaric way: if it turns out, as I expect it will, that the military-industrial complex employs over half the Soviet Union’s population (in the Russian republic the factories and plants of the military-industrial establishment employ 82 percent of the population), then we must deal with the problem while protecting these people. The military-industrial complex employs many first-class technicians and specialists, and special programs of social welfare will be needed before many of them can take part in civilian production.

Attempts to solve the immensely difficult problem of the military-industrial complex should start from the obvious fact that our country needs military forces only for its defense. They should, moreover, be highly mobile and capable of being integrated with the European security forces necessary to resolve crises that threaten to become global, such as today in the Persian Gulf. Perhaps such a new structure of forces would best suit the republics, which would, as independent states, be delegating power to the army.

A third contradiction derives from the absence of civil society in Russia and the Soviet Union as a whole. In our amoeba-like social life people are not seen as having different interests or as belonging to different groups. In this society everyone or almost everyone is supposed to be the same; everyone works for the state, everyone is on salary, everyone is on a leash. Most people have not expressed a desire for anything new, which seems clear evidence that an enormous number of people in our society do not want positive changes in it. We should not have hopes that even greater dissatisfaction with the empty shelves in the shops will create change, or that changes will come about in reaction to increasing instability, or ethnic tensions, or rising crime. Unfortunately, there is still no intense desire to transform social relations so that people may own property, and no sense that a new or different social direction is emerging. Many people continue to have the same old illusions about the great opportunities that may still be open to them under the existing system. On one hand, there has been a very pronounced leveling of society accompanied by a mood in favor of equalizing, and, on the other, a willingness to live in shabby circumstances and to disregard the humiliation involved as long as a guaranteed minimum of social goods is made available. This cast of mind has a conservative effect on the processes of transformation that are taking place and suggests a deep lack of civic and self-awareness in our society.

2.

The president’s recent capitulation to conservative forces, in the primitive conditions of civil society that I have described, puts in doubt the possibility that any effective economic program can be carried out and makes more acute the question of the political system throughout the Soviet Union and at all levels—in the republics, between the republics, in cities and other local governments. The crisis of power is not only a crisis among power holders—it is linked to the deformation of consciousness that affects the entire society.

We have a reversed scale of values in that powerful social forces are working to reduce the vitality of social and individual consciousness and to promote states of mind that are immature, atavistic, and “retro.” This makes our society highly unstable and diverts our creative energies, thereby depriving us of the capacity to resist uncivilized forms of collective behavior. In one sense we live in a situation in which society has coincided with the state and as a result, the mafias that are part of the state bureaucratic structure have imposed themselves throughout society, including the underground economy where everything can be bought. (Unlike the Sicilian variant, our domestic mafia operates from the top of the social and political structure to the bottom, which occurs nowhere else in the world.)

In addition, our society is broken in spirit, and social weariness has become one of the reasons why so many people are lacking in social consciousness. The recent proliferation of crime and reports of criminal activity suggests that criminals are becoming acknowledged as “normal”; while the national health standards have clearly declined. Another index of the profound illness of our society can be found in the many thousands of intellectuals who, in the hope of finding work abroad, stand in long lines for exit visas. In a society that has no serious demand for creative ideas and solutions, such a drain of talent is not surprising.

Many of our people seem reduced to a condition resembling that of cattle and, what is more frightening, they do not ask to live any other way. Many are ready to settle for this condition or something only a little better. In such a society, attempts to raise the level of civic spirit, particularly among Russians, is marked by the same contradictions. Take the most recent publication by Aleksander Solzhenitsyn. I agree with him on many points—his opinions on land distribution and property for example—even though I cannot agree with his refusal to consider the Ukrainian and Byelorussian people as historically independent. He is right that the years of Soviet rule have brought us to an unattractive, a horrible state of affairs. No doubt revolution is a catastrophe, and the October Revolution was a tragedy. But I think limiting oneself to that statement is not enough. For the main questions remain unanswered: What made this particular revolution possible, and how did the Bolsheviks become possible? How could so many people have been fooled for three quarters of a century by the Marxist-Leninist ideology that Solzhenitsyn considers entirely alien to us? How could it have happened?

And here—although I know I risk drawing fire in saying so—the point to be made is that Lenin’s Bolshevism was preceded by a people’s Bolshevism. There is no point in trying to shift the blame away from the people. The heightened sense of social justice and the centuries-old hatred of oppressors, which gave rise to Razin and Pugachev and later to Tkachev, Lenin, and Trotsky, have deep national roots. It was and is very characteristic of Russia to have the people at the “bottom” harshly subordinated to the people at the “top,” and for people generally to be subordinated to the state: such relations were formed back in the twelfth century. The eternal oppression in Russia created a reaction against it of intolerance, aggression, and hostility; and it is this oppression and the reaction to it that create cruelty and mass violence. It is true that the policies of the Bolsheviks did not derive from the will of the people, but the people participated in those policies, and took part in the mass terror. The relation between “power and the people” in Russia is a complex one, and the prospect remains that our country may continue to develop along authoritarian lines.

We often hear it said that “the Soviet Union is not Russian—it is not a Russian entity.” But in my view a civil society will not come into being here until people recognize that this statement expresses an extremely dangerous illusion, which can only confuse public opinion in general and the democratic forces in particular. The USSR is, in fact, the continuation of the Russian Empire; and Russia is not only the victim of the imperial will, but also an imperial force in itself. Russia’s misfortunes spring not only from the fact that it sustains the other republics but from its having preserved its deep imperial tendencies.

The proposition that Russia’s hope for survival is to leave the union, which one often hears, should be posed differently. The very idea is chauvinist and dangerous. The real question to be asked is not whether Russia will leave the Soviet Union but whether the Soviet Union will cease to embody the imperialist principle. And yet, if perestroika, as Gorbachev defines it, gets a quick fix in the form of financial and technological aid from the Western democracies, the Soviet empire is still quite capable of imposing its power over the looming crises in its component nations, even while losing a part of its territories, and thereby prolonging its own existence.

The West is apparently prepared to help the “great reformer,” both as a sign of gratitude for the freedom he allegedly gave to the countries of Eastern Europe and out of fear of a “social Chernobyl,” an elemental disintegration of the empire. And the consequences of that disintegration could indeed be devastating and entirely unpredictable. That the Soviet Union has started taking nuclear arms out of the Baltic states, Byelorussia, and Transcaucasia (reports to this effect have appeared in the press) shows that the country’s leaders have not ruled out the possibility of civil war (How indeed can it be ruled out if it is already blazing on the periphery?), and are preparing for the worst.

The fourth contradiction lies within public consciousness. After all, the people speaking out against a market economy today are not simply extremist conservatives, but make up almost a majority of all our citizens. For them, the prospect of a market economy resembles a Stalinist exercise in logic: “I’ll force you to be happy, you bastard!” This time, people say, it is the market economy that is going to force happiness on us.

Unless the Soviet Union becomes part of the larger European and world economy, it cannot, in my view, be saved by any economic program. We speak a different economic language from the rest of the modern world, and we have yet to show ourselves capable of trading, or of carrying on a political, economic, or financial dialogue, or even dealing in natural exchange, barter.

3.

These four contradictions will be immensely difficult to resolve; it would be the worst, the most hypocritical, illusion to claim otherwise. As a historian I believe that it is not only the deepening crisis of the system and the regime that is an obstacle to overcoming these contradictions and to moving to a better life under the new economic systems that have been proposed. The current crisis coincides with another, larger one, which began in the nineteenth century—the crisis, or perhaps the exhaustion, of this Eurasian civilization, with its egalitarian, statist ethic and its imperial forms and values. This civilization is no longer workable. The autonomous elements within it of Buddhist and Byzantine Christian civilizations, elements that were capable of developing on their own, were suppressed, and are only now getting a chance to strengthen themselves—a subject that deserves independent treatment. What is important now is that in the long-term crisis we face, coming as it does on top of the collapse of “Eurasia,” the possibility of authoritarianism and its harsher form, dictatorship, remains a grave danger.

In his speech to the all-union parliament on November 17, the president, in my view, took a step beyond the authoritarian regime of Gorbachev-Ryzhkov and toward dictatorship. In this confident speech he admitted no error and had nothing to say about such vitally important questions as land ownership, private property, business enterprise, and the independence of the republics—nothing about carrying forward the long-hoped-for social and economic transformations that have now been blocked. On the contrary, much of what he said forced me to consider what is now happening as the preparation for dictatorial rule. I mean Gorbachev’s emphasis on the army (which needed, he said, to be defended), on the forces of public order, on the precedence of the Council of Federations, which is newly empowered to decide practically all vital issues. I mean as well the proposed ban on activities that could cause the states to “fraction”—i.e., to pull away from the union—which is the basis of his approach to a union treaty, and which ignores the reality of popular feeling inside the republics. I mean, finally, his appeal to the Communists for their energetic support for his new course.

The Fourth Congress of People’s Deputies became another vivid example of the unwillingness of the conservatives, headed by Gorbachev, to begin deep structural transformations, for example by making the republics independent, by legalizing private property, and by giving up in deed and not just in words the Party monopoly on power. These conservative forces would like to retain the discredited word “socialist” as part of the name of the state and—notwithstanding the will of many republics—they insist on seeing that state as a single unit.

It began to look as if the Fourth Congress would be a complete triumph for Gorbachev. After all, 95 percent of the deputies voted for all his basic resolutions. And then suddenly, astonishingly, Shevardnadze announced his resignation. How was this to be understood? For he is the president’s closest friend, the most passionate proponent of deep changes. And what about his statement on the danger of dictatorship? Of course, it was so vague that Gorbachev was able to say it hinted at things that had no basis in fact. The reasons for this mysterious step by one of our highest officials will not be clear until Shevardnadze actually leaves, or does not leave, his post.

The one thing that is clear is that there is now an all-encompassing crisis of power. It began with a demonstration of the impotence in the executive, as was shown in the steady expansion of the president’s powers and his growing dependence on the police agencies and the army, on the control of force. Then the crisis came to include the legislative branch. The Supreme Soviet handed over its legislative functions without a murmur to the president. Now it is a crisis within the ruling circle: we see profound differences on the central issues between Shevardnadze and the rest of those on our political Olympus, including his differences with Gorbachev.

Having shown that these differences exist, the minister of foreign affairs did not wish to reveal what they were or give a convincing reason for his resignation. And that may mean that he does not want to burn his bridges, that he is leaving open the possibility of being “talked into” remaining in office. In that case, we have simply seen a clever politician use the familiar tactic of anticipating moves against him; and when we look back at what happened to Ligachev, Yakovlev, and Bakatin we see it may be a wise step. Gorbachev has shown his ability to sacrifice his comrades when necessary. And the brazen attacks on Shevardnadze by the conservative military officers Alksnis and Petrushenko must have given him pause. If his motive was to protect himself, that was understandable. But one would hope for more than that from a man like Shevardnadze.

I would like to be wrong, but I am concerned not to betray reality by circulating yet another illusion. I see tragedy in Gorbachev’s fate: the initiator of perestroika may become its destroyer.

—December 27, 1990

—translated by Antonina W. Bouis

This Issue

January 31, 1991