A brief account of Baudelaire’s brief life would go somewhat like this. Charles Pierre Baudelaire was born in Paris on April 9, 1821. His father, a retired civil servant and amateur painter, died on February 10, 1827. The idyll the child enjoyed with his adored mother came to an end a year and a half later, when on November 8, 1828, she married an army officer, Jacques Aupick. Charles was sent to school in Lyons and later in Paris, but he was expelled for unruly conduct. At the age of eighteen he contracted gonorrhoea. In 1841, on the strength of a small inheritance from his father, he started upon a literary and bohemian life in Paris. The Aupicks, hoping to retrieve him from bad company, sent him on a long sea voyage, but he jumped ship at Saint-Denis de la Réunion and made his way back to Paris.

In 1842 he contracted syphilis. At about the same time he took up with his first mistress, a minor actress, Jeanne Duval. On November 7, 1844, in a further attempt to rescue him, the Aupicks arranged to have a lawyer, Narcisse Désiré Ancelle, appointed conseil judiciaire to him and put in charge of his financial affairs.

Constantly in debt, Baudelaire tried to elude his creditors by moving from one lodging to another. When that device failed, he appealed to his mother for money. He was a young man about town, interested in art more than in literature. The first occasion on which he made a serious attempt to gain a hearing was in a long review of the Salon of 1845. Apart from a few friends, no one paid him any attention. On June 30, 1845, he tried to kill himself, probably (as Claude Pichois suggests) because of “the relative failure of his Salon, a desire to bring pressure to bear on the family members who had humiliated him with the conseil judiciaire, or a deeper ennui, a feeling that life had lost its savor.”

When the revolution broke out in February 1848, Baudelaire got a shotgun and took to the barricades, shouting, “We must shoot General Aupick.” But his interest in revolution soon lapsed. In 1852 he tried to leave Jeanne Duval: she was far gone in drink, dissipation, and despair, and while he treated her with sympathy and consideration, he knew the affair was a disaster. He was also pursuing other women, notably Aglaé-Joséphine Sabatier, a professional model. In 1854 he entered upon a relation with Marie Daubrun, a more serious actress than Duval.

On June 25, 1857, Baudelaire published Les Fleurs du mal, and on August 20 he was fined 300 francs for its “obscene and immoral passages or expressions.” Six poems were ordered to be removed. For the second edition, issued on February 9, 1861, he added thirty-five new poems and arranged the entire collection in a more pessimistic order. On January 23, 1862, he confided to his journal that he “felt a strange warning, the wind of the wing of insanity,”—“j’ai subi un singulier avertissement, j’ai senti passer sur moi le vent de l’aile de l’imbécilité.” On April 24, 1864, he went to Brussels to give a few lectures. He hated Belgium, was bored by Brussels, and planned to write a book called Pauvre Belgique! He stayed on, it appears, mainly because he felt too dispirited to go anywhere else. His health deteriorated, he suffered a stroke and lost the power of speech. On April 14, 1866, his mother arrived to bring him back to Paris. He died there at forty-six on August 31, 1867. Several of his writings were published after his death; the third edition of Les Fleurs du mal in 1868, Le Spleen de Paris in 1869, and Mon Coeur mis à nu in 1887.

Pichois’s Baudelaire is an ambitious biography of the poet. It was first published in Paris in 1987, a big book, 704 pages, ascribed to Claude Pichois and Jean Ziegler. The book under review is an abridged version of the French original. The dust jacket attributes it to Pichois “in collaboration with Jean Ziegler,” but the title page gives it to Pichois and refers to “additional research by Jean Ziegler.” Graham Robb’s translation retains the original sequence of chapters, reproduces all photographs and cartoons, and achieves relative brevity by summarizing rather than quoting minor letters and other documents. The translation reads well, but Robb sometimes reduces the force of the French. When Baudelaire writes to his mother to complain about Jeanne Duval, “Je me suis amusé à martyriser, et j’ai été martryisé à mon tour,” it’s hardly adequate to have him say, “I amused myself with torture and was tortured in my turn.”

There are signs of indecision in the book. “This biography is not intended to be a history of Baudelaire’s thought,” Pichois says, but two hundred pages later he refers to it as “the story of his intellectual life.” It’s clear that Pichois wrote the book to remove the accretions of legend and myth that have gathered upon Baudelaire’s name in social and cultural history. But it’s not clear whether he regards Baudelaire’s poems, essays, and letters as making up his true life, or as documents illustrating a life lived chiefly through domestic, sexual, and social experience. The experiences that Baudelaire imagined are often hard to distinguish from those he was in a position to transcribe.

Advertisement

The matter is complicated by the fact that Baudelaire, as Pichois shows, oscillated between despising the French bourgeoisie and seeking its approval. There is much in Pichois’s biography to support Roland Barthes’s argument that Baudelaire often paid tribute to the social institutions his poems appear to reject. He offered his play L’Ivrogne to the manager of the Gaîté, flattered Sainte-Beuve, canvassed votes for the academy, and wanted the Legion of Honor. Baudelaire did these things, and gave them his credence up to a point; or rather, according to a pattern which Barthes describes, by which Baudelaire cursed and abandoned such social gestures almost as soon as he had consented to them. His second thoughts on them were invariably dismissive. Recalling in Mon Coeur mis à nu his revolutionary enthusiasm of 1848, Baudelaire dismissed it as mere desire for vengeance: goût de la vengeance; plaisir naturel de la démolition. February 1848 was charming, according to his second sense of it, only because it reached the height of absurdity—“par l’excès même du Ridicule.”

It is a commonplace, but one worth repeating, that Baudelaire presented himself as a poet of the city, and in that capacity as an exemplar of what he called Modernity. We think of him as the inventor of a new kind of poem, in which the poet wanders through the streets of a great city and derives from many such experiences a new tone, indeed a new emotion. In that respect, Baudelaire was the decisive figure in a tradition of modern poetry that culminated but didn’t end in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and Hart Crane’s The Bridge. Eliot recognized the nature of this achievement when he said that for him the significance of Les Fleurs du mal was summed up in the first lines of “Les sept vieillards,” Baudelaire’s vision of the swarming city in which ghosts accost the passer-by in broad daylight:

Fourmillante cité, cité pleine de rêves,

Où le spectre en plein jour rac- croche le passant!

“I knew what that meant,” Eliot said, “because I had lived it before I knew that I wanted to turn it into verse on my own account.”

How Baudelaire lived it is the matter of Pichois’s biography and of several essays in Leakey’s book. It is also Baudelaire’s own theme, explicitly in “The Painter of Modern Life,” implicitly in his essay on Delacroix. The city is the scene of Modernity, and the distinctive element of Modernity is “the transient, the fleeting, the contingent; it is one half of art, the other being the eternal and the immovable.” The modern artist walks about the city, observing everything, like “a prince enjoying his incognito wherever he goes.” Not content to transcribe or otherwise represent what he sees, the artist gives appearances a new life, partly his own. Baudelaire says that the artist “distills the eternal from the transitory,” but this formulation is equivocal because it appears to retain “the eternal” as the criterion, the better half of the relation with “the transient.” Baudelaire rejects any theory of a unique and absolute beauty, but by retaining “the eternal” as criterion, he qualifies his rejection of the theory. He doesn’t value “the transitory” for its own sake, even though he insists on its presence as an element in the modern sense of beauty. So his position is not as radical as Walter Pater’s in The Renaissance, where Pater claims that “art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments’ sake.” The highest quality, to Pater, was local intensity, not an intimation of eternity. In his essays, Baudelaire was susceptible to the very antitheses his poems qualify or disrupt; juxtapositions of God and Satan, ecstasy and horror, spleen and idéal, spirituality and animality. The boisterousness of his style, in the essays, arises from the bravado with which he produced these antitheses and divided the world between them.

There is no contradiction between Baudelaire’s being a poet of the city and his imagining, in several poems, a pastoral or Gauguinesque “vie antérieure.” Crowded city streets did not undermine his sense of an affinity between sensory events; as in “Correspondances,” where perfumes, sounds, and colors answer one another:

Advertisement

Comme de longs échos qui de loin se confondent

Dans une ténébreuse et profonde unité,

Vaste comme la nuit et comme la clarté,

Les parfums, les couleurs et les sons se répondent.

City streets may not have given Baudelaire what daffodils and valleys gave Wordsworth, but they didn’t limit his imagination or his desire. Wordsworth divined intimations of mortality from recollections of early childhood in rural England; Baudelaire from his first years with his mother. Genius, Baudelaire said, is the ability to recapture one’s childhood at will. There is a difference of emphasis between the two poets. Baudelaire emphasized a child’s curiosity, while Wordsworth made more of the child’s companionship with the elements. The difference may appear slight, but it becomes much greater when Baudelaire associates the artist with the flâneur, the city stroller and the dandy. In The Prelude and “Upon Westminster Bridge,” the pleasure Wordsworth takes in London depends upon his not seeing it too closely. In “The Painter of Modern Life” the pleasure Baudelaire ascribes to the artist Constantin Guys is gained by close and indiscriminate attention to the streets of Paris; it is heightened curiosity, a child’s will extended in maturity. It is sufficient that Guys finds everything he sees on the streets interesting. Being interesting is just as good as being beautiful: as an emphatic instance of the picturesque, it doesn’t have to be questioned for its disposition of the transitory and the eternal. After such promenades, Guys goes back to his studio, and draws what he has seen, from memory. Representation is not the point. Guys’s drawings emerge not from a punctual relation to the things he has seen but from his later recollection of them, when their purely formal possibilities have been grasped. The things seen, according to Baudelaire, are reborn on Guys’s paper, “natural and more than natural, beautiful and better than beautiful, strange, endowed with an enthusiastic life, like the soul of their creator”—“comme l’âme de l’auteur.” It is as if the scenes of Parisian life now achieved, in Guys’s sketches, what they have lacked, a destiny in form.

In Baudelaire’s poems, the supreme experience is not the Wordsworthian fulfillment of seeing into the life of things, but of being seized by a particular appearance, irrefutable because arbitrary. He called the experience “fascination,” and it is his version of the Wordsworthian Sublime. Whether it is described by Edmund Burke, Kant, or Wordsworth, it is the experience of being driven beyond oneself or beside oneself, forced beyond the categories of one’s thought. The Alps gave Romantic poets this frisson, this vertigo in the irrefutable presence of the inexpressible. Fascination was Baudelaire’s version of it, an urban apocalypse which could not be anticipated though it might be sought. In “A une passante” the glance of a passing woman not only brings the poet to life again but drives him to imagine the passion he could have felt for her, and to fancy that she has known as much—“O toi que j’eusse aimée, ô toi qui le savais!” In “Les petites vieilles” the poet enjoys the secret pleasures—“des plaisirs clandestins“—of looking at the old women and divining their lost lives—“je vis vos jours perdus.” In these poems, to be fascinated is to be seized by an appearance, to have the present moment replete with it. Past and future may be posited, but only notionally, as if in an attempt to give the vertigo an origin and an end.

Baudelaire’s interest in the people he sees on the streets of Paris is, as Paul de Man has remarked, poetic rather than humanitarian. The poet nearly acknowledged this in “Les petites vieilles” when he said that in the sinuous folds of cities everything, even horror, turns to magic:

Dans les plis sinueux des vieilles capitales,

Où tout, même l’horreur, tourne aux enchantements….

But it turns to magic only in the poem, the movements of syllables, words, and lines. The magician sees himself impelled to spy on these “decrepit and charming” old women:

Je guette, obéissant à mes humeurs fatales,

Des êtres singuliers, décrépits et charmants.

It is easy to be stuffy about this, but “décrépits” seems to me too close to “charmants” for decency. Baudelaire’s “humeurs” are only notionally “fatales,” he will not die of them. Even in the love poems, like “La Chevelure,” one responds to the gorgeousness of the language and only as an afterthought to the fact that nothing remains of the beloved woman, not even her hair; the rhythms of poetic transcendence displace the body that provoked them. In the end, the woman is merely the scene of the poet’s dreams—“l’oasis où je rêve“—and the gourd from which he drinks the wine of memory—“la gourde/Où je hume à longs traits le vin du souvenir.”

I should note that Baudelaire himself raised the question of the artist as opportunist in several of the “little poems in prose” which Edward K. Kaplan has translated as The Parisian Prowler. Leakey argues in several of his essays that most of the poems in Les Fleurs du mal were written when Baudelaire was a young man, as early as 1843–1844. If so, it makes ethical sense that after the 1861 edition of the book, Baudelaire proposed to write as many as a hundred prose poems. The ones he completed are rueful or ironic reconsiderations of conventional notions about art and the artist. Some of these notions, involving the heroic role of the poet and the purity of imaginative acts, are somewhat grandly accepted in Les Fleurs du mal. They receive far more severe treatment in The Parisian Prowler, a bundle of anecdotes, fables, and parables from which no romantic soul could derive comfort.

In a letter of 1862 to his publisher, Baudelaire wrote of his dream of “the miracle of a poetic prose, musical without rhythm and without rhyme, supple enough and uneven enough to adapt itself to the lyrical impulses of the soul, the undulations of reverie, and the shocks of consciousness.” This “obsessive ideal,” he said, “sprang from the frequenting of great cities and the intersecting of their countless relationships.” In “Les Fenêtres”, one of the “petits poèmes en prose,” the poet revokes the claims of the imagination he made in “A une passante” and “Les Petites Vieilles” and he no longer talks of the rebirth in art of things seen in ordinary life, as he did of Guys’s paintings. Now he looks out his window, sees an old woman who never leaves her apartment, and imagines the story of her life; “and sometimes I tell it to myself weeping.” He goes to bed, “proud of having lived and suffered in others than myself”—“dans d’autres que moi-même.” If you ask him, “Are you sure that the story is true?” he answers: “What does the objective reality matter, if it has helped me to live, to feel that I am, and what I am?”

Again in “Les Foules,” Baudelaire repeats many of the motifs and claims of “The Painter of Modern Life,” especially the quasi-sexual, indeed promiscuous felicity of entering the crowd:

The poet enjoys this incomparable privilege, that he can at will be himself and another. Like those wandering souls in search of a body, he enters, whenever he chooses, into everyone’s character. For him alone, everything is vacant; and if certain places seem closed to him, it is because he considers them not worth the bother of visiting.

But in “Les Foules” Baudelaire acknowledges, as he doesn’t in “The Painter of Modern Life,” that the artist, going into the crowd for a binge of vitality, does so “at the expense of the human species”—“aux dépens du genre humain.”

The prosecution of Les Fleurs du mal turned Baudelaire into an icon, the type of poète maudit. He soon endorsed the typology by adding to his poem “L’Albatros” in 1859 a final quatrain in which “Le Poéte” is represented as sharing the fate of an albatross, captured and tormented by bored sailors: this “prince of the clouds” is now exiled on earth, an object of scorn, his giant wings impeding him as he tries to walk:

Le Poéte est semblable au prince des nuées

Qui hante la tempête et se rit de l’archer;

Exilé sur le sol au milieu des huées,

Ses ailes de géant l’empêchent de marcher.

Over the years, many writers collaborated in turning Baudelaire into a symbol: Hugo, Verlaine, Swinburne, Proust, Mallarmé. In Mallarmé’s “Le Tombeau de Charles Baudelaire” the poet’s Shade is “a guardian poison, always to be breathed though we die of it”:

Celle son Ombre même un poison tutélaire

Toujours à respirer si nous en périssons.

Gide, Laforgue, and Valéry added footnotes to the cluttered text of Baudelaire’s martyrdom. T.S. Eliot captured him for Christianity by virtue of his belief in Original Sin:

Baudelaire perceived that what really matters is Sin and Redemption…. In all his humiliating traffic with other beings, he walked secure in this high vocation, that he was capable of a damnation denied to the politicians and the newspaper editors of Paris.

Sartre’s Baudelaire encouraged readers to believe that nearly everything in Baudelaire may be attributed to his conviction of being abandoned by his mother in her second marriage, and to the defects of character which ensued.

The great merit of Pichois’s book is not that it answers these and other questions but that it leaves readers free to take them up again in a new situation as free of lore and legend as it can be. There are many issues to be debated, among them the question of blasphemy as expression of faith, Baudelaire’s strange interest in comedy and caricature, the bearing of sadomasochistic fantasy upon “A celle qui est trop gaie” and “A une madone,” Baudelaire’s sense of “the New”—“Au fond de l’Inconnu pour trouver du nouveau!” There is no point in claiming that the several major interpretations of Baudelaire—one thinks of Pierre Emmanuel, Georges Bataille, Michel Butor, Jean Starobinski, Victor Brombert, Leo Bersani, Marcel Ruff, Pichois himself, and Leakey’s Baudelaire and Nature—have been reconciled. But the tone of Pichois’s book makes it clear that to read Les Fleurs du mal it is not necessary to kidnap its author.

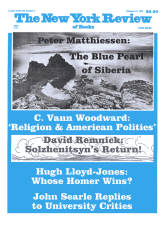

This Issue

February 14, 1991