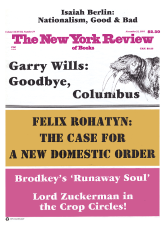

Harold Brodkey’s big book The Runaway Soul appears before us trailing a long prepublication history, many high commendations, and a counterfoil of questioning if not derogatory comments. Associated and overlapping materials have already been published in two collections of short stories (First Love and Other Sorrows, 1958, and Stories in an Almost Classical Mode, 1989). There has also been an extraordinary amount of gossip and opinionated talk about the author’s career, much of it provoked by Brodkey’s own personality, some of it inspired by the special reach of his literary ambition, even more of it centering on the prolonged and apparently turbulent process of editorial consideration and reconsideration, which has now resulted in a first, but monumental, novel by an author entering his sixties.

At first survey The Runaway Soul resembles, and in many detailed passages it reads like, yet another example of that familiar fictional type, the novel of development, for which German criticism has provided the name of Bildungsroman. Such a book typically describes the process by which a sensitive young person (often the artist himself) grows up, declares his values, and climactically produces…the very novel we have been reading. Among the literary ancestors bestowed on Harold Brodkey by critics have been such predecessors in self-exploration as Thomas Wolfe, James Joyce, and Marcel Proust. Milton and Wordsworth have been mentioned as well, and there is nothing to keep one from invoking the names of Goethe, Flaubert, and Thomas Mann, any or all of whom may quite possibly become, in time, the standard references with which to discuss the soul-forming fiction of Harold Brodkey. But now the major work of fiction is actually to hand, and a first step might be to look directly, and if possible analytically, at the book as it has been written. We deal here with an important work, in scale, in emotional pitch, in intellectual reach; best to have the basic facts clearly on record.

The Runaway Soul is primarily about the developing mind, body, and character of Wiley Silenowicz. His name at birth was different—perhaps Aaron Weintrub or Cohn or even Buddy Brodkey. The reason for this abundance is that, at the death of his natural mother when he was aged two, Wiley was taken into the family of S.L. (Samuel Leonard or Samuel Louis) Silenowicz and his wife Lila (or Leila)—who already had a daughter, Nonie, some ten years older than little Wiley. Wiley’s (or Aaron’s) natural father was a junk dealer—a rough and uncouth man, no kin to either Silenowicz. There is a story that he sold them the frail and sickly infant for a paltry sum because Lila wanted a child who would bring back to the family the wandering affections of her husband. It was a rash venture, but it worked; S.L. was or quickly became more devoted to his adopted son than to his wife or daughter. That produced predictable discord; but the devotion of a housekeeper, Anne Marie, pulled Wiley through a wretched infancy, and for a while the situation of the Silenowicz ménage appeared to stabilize.

S.L. was a small businessman engaged in a set of nondescript, precarious enterprises, foolishly extravagant when flush, but easily rendered despondent by failure. His wife, Lila, was a shrewd, hard-tempered, witty vulgarian with streaks of unforeseeable good temper. They lived in a suburb of St. Louis near the river; they observed their own formulas of respectability; they worried about educating Wiley, who had been identified at school as precocious, but not so much about their own child, Nonie, who hovered on the fringe of being academically backward.

Nonie was also a sadistic, hysterical, and pathologically jealous thorn in Wiley’s young side. The most traumatic of her scenes occurs during a thunderstorm when she is just thirteen years old. (By elementary arithmetic Wiley must be just three; but Brodkey is not limited in describing the scene to what a three-year-old could consciously have realized. The terror and incoherence of events are described as in a phantasmagoric nightmare—violently and vividly, but at the expense of inserting his mature literary perceptions into a picture composed behind three-year-old eyes.) Terrified by the storm, Nonie shrieks and howls; she beshits herself; she demands that her father, or Anne Marie, be sacrificed to the lightning. And, as we learn belatedly, she almost succeeds in carrying Wiley off into a dark closet where she will throttle him.

This will not be a new adventure for her. After Nonie was born, the Silenowiczes had two sons whom they left, successively, in the care of Nonie—and whom, on their return home, they found dead. Nobody says, and nobody doubts, that she was somehow responsible. For such is Nonie: losing a tennis game, she hacks with her racket at the opponent’s wrist and ends the game that way; while she is playing another game on a porch, her antagonist falls (or is pushed?) to the sidewalk and dislocates her shoulder. She is a cold as well as a ruthless little bitch; when a few years later major misfortune strikes (her father suffers the first of a series of strokes, while her mother is diagnosed with cancer), Nonie does not hesitate. She gets a civilian job with the army, leaves Wiley to take care of his dying adoptive parents, and moves herself away.

Advertisement

The last years of Wiley’s life in St. Louis (before, by unexplained circumstances, he is transferred to Harvard College) are thus spent in the house of his dying parents—his mother half mad with pain and shame at the squalor of her circumstances, his father haunted by grief and humiliation. And the boy is a study too—his pride at “behaving well” toward the doomed parents mingled with anguish at the waste of his youth. Here the relevant comparison is with Dostoevsky, and it is a comparison in which Harold Brodkey does not come off at all badly. He has a strong feeling for the ignobly decent side of life in the suburban shallows and a deep sense of the little boy’s helpless horror that can express itself only in convulsive vomiting. Toward the end of the St. Louis section, he begins to reach into the lower depths, the disintegration of the Silenowicz family being set forth with a controlled intensity that is impressive.

Brodkey has no interest in, or reason to explore, as Faulkner did, the history of the land, the vast commercial highway of the river, the saga of the frontier, the heritage of the Civil War, or the mean pathos of Main Street. He does not recognize the existence of a black community. His is mainly an urban family drama—not the story of Wiley as a member of his family, but of the family seen as appendages to Wiley. Three strong voices fill the first part of the book—Daddy (S.L.), Momma (Lila), and Nonie. They would be impressive voices in any company; even S.L., when he is nuzzling with Wiley, and soliloquizing about himself, has the kind of awful weakling’s fascination that one remembers from Christina Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children. Most appealing of all is the flashy performer Lila, who not only acts, directs, and criticizes the performances of the entire extended family, but judges people with the finality of a meat cleaver. And at any unexpected moment there is always the chance that Nonie will break in with a shriek or a moan from her private hell. But where in this chorus of strident voices is there any room for the hero, Wiley Silenowicz?

Wiley starts on his fictional career with a tremendous handicap, in that he is supposed to be preternaturally intelligent. The more frequent word used in the novel (and often by Wiley about himself) is “smart.” The problem for such a character, and for any such character, is that if he actually says something intelligent (as, for example, Stephen Dedalus does), he comes off as a pedant or a prig; if he talks the common dialect of his unwashed contemporaries, what’s so special about him? The worst thing he can possibly do is talk repeatedly or at length about his own brilliance. On all these scores, the task of presenting Wiley Silenowicz in some approximation of his own words clearly faces Harold Brodkey with a set of formidable constraints.

While he is in the infant stage, Wiley naturally has few words of his own. But since we have to have some access to his consciousness, Brodkey provides him with imaginary dialects—sometimes like those half-impressions, half-conceptions that Nathalie Sarraute baptized “tropismes,” sometimes frankly metaphorical, occasionally erudite, and ultimately private associations of his own. Both exterior action and spoken dialogue are thus absorbed into interior monologue and phantasmagoria, while the sense of story or plot is frustrated. Stoppage is emphasized by the division of the text into separate units defined either as a period of time or topically as the action of a particular character. The character dealt with in one section commonly has little or nothing to do with characters from other sections. The time periods are not only separated from one another, but often inverted, so that a “later” unit in fictional time comes before an “earlier” one in the sequence of the book.

For example, after getting born in 1930 on a single snappy page, Wiley is moved for four brief units to 1944 when his adoptive father has just died, then back for three units to 1932, forward for a session with Ora, his Harvard girl-friend, in 1956, back for two quick episodes in 1932, then back to 1956 (but twenty minutes later) to complete the transaction with Ora. This pattern of discontinuity, which is expanded later in the book by the addition of three earlier sexual or quasi-sexual partners (Leonie, Remsen, and Cousin Daniel), offers no particular difficulties to a reader of modern fiction. It impedes and confuses, to be sure, the autobiographical development of Wiley. It sets him apart from his acquaintances, as if he were a student and they were specimens. It does not form a strong symbolic pattern, as the Easter-week disarray of The Sound and the Fury clearly does. Neither does it divide the emotional life of Wiley Silenowicz into a recognizable sequence of experiential units. What he learns from one experience (if anything) does not carry over to another or the others.

Advertisement

When he is thirteen years and eight months old, he is skillful enough to tantalize Cousin Daniel, whom he guesses to be homosexually inclined. When he is just fourteen, accident or the machinations of Nonie bring him up against a girl named Leonie, who is a decade older than he and already engaged to a military man; but none of that hinders her from a long-drawn-out spell of heavy necking with adolescent Wiley. With a boy named Remsen, when Wiley is fifteen, things progress to the point of mutual masturbation. (Even the marathon session of copulation with Ora ends in an act of masturbation.) Yet it is not explicit that any or all of these acts have led nowhere or ended in disappointment; they do not make up a sentimental education or an approach to one.

No more do they seem to lead to an overwhelming vision of any sort. Wiley Silenowicz or Harold Brodkey (if one may venture the distinction) once had some sort of apocalyptic vision. (As described in the last of the Stories in an Almost Classical Mode, an angel appeared in Harvard Yard on October 25, 1951; numerous people, including the narrator, observed it and discussed its presence.) But in the end there seem to be only negative or conjectural things to say about it. Like the Ding an Sich, the Beatific Vision, or Nirvana, the transcendental vision seems to be very little in itself, apart from the code in which one has been conditioned to define it. Brodkey himself doesn’t so much describe his vision as hide it behind a veil of shimmering words.

In fact, Brodkey/Silenowicz is acutely conscious of the inadequacy of language to render even mundane experiences. He is very fond of using vague all-purpose words like “thing” and “stuff” to gesture at some concept that he doesn’t want, or doesn’t feel able, to particularize. He suggests, invokes, elicits, tantalizes; he intimates that on some level or other, something more splendid exists than he or we can possibly express. It is only rendered, in fact, by an expression of despair at the impossibility of rendering it. As part of an adolescent’s vocabulary, deliberately dumb formulations like “thing” and “stuff” might contribute to the coloring of an American scene; but as Brodkey belabors them to make an ontological point, they self-destruct. A sentence like that on page 459 reduces the mannerism to its basic absurdity: “I love the amateur thing, the semi-amateur thing of a lot of the stuff, most of the stuff in him.” At this point we are not far removed from “yeah, man, what I mean, you know?”

Proverbially, the high metaphorical style flourishes in the thickets of sexual passion, and Brodkey’s stylistic variations illustrate some of the problems as well as the potentialities. For example, a story titled “Innocence” deals mostly with sex as a problem. Orra, a girl of high social standing, staggering beauty, and considerable experience, has been unable to achieve orgasm; indeed, she has decided that she is permanently incapable. Wiley, working slowly, persistently, and inventively, brings her, after twenty-four pages, to a crashing climax, figured in the frantic beating of three sets of angelic wings. It is an elegant and audacious yet unmistakably literary metaphor.

We next meet Orra (minus one of the “r’s” in her first name) as a personage in the novel. She and Wiley, having completed their Cambridge studies, have transferred to New York and have been living together for some four years. If she has had trouble with her orgasms, it has long since been surmounted. Wiley is a published writer now, with an acquaintance of important editors and literary admirers; whether he is more of a celebrity than she is is apparently a topic of daily conversation between them. While the first conversation with Ora takes place in bed, the mode of reflection is at once less focused and more worldly.

Like a general observing the topography of a place, I observed her from above although I was mostly under her, but an aerial view is what I had, as if I were floating in the dark air outside the sphere of light around me and her in the bed. She was faintly on her side but her shoulders and cunt were flatly on top of me. Sexual hallucination hummed quietly in me—or imagination, if you prefer. Her arm that extended over my chest touched the bed on the other side of me: that arm rested on the side of its wrist. Her hand was bent ineffectually and curled upward into the air. And her breasts and ribs, the odd skin-covered motioniness of those warm and complexly vibrating and slightly oozy-tissued and somewhat hottish group of structures pressed against my own chest—my half-athletic, pectoralled, sometimes-praised chest…I mean some kids at college had commented on it. But I was saying her torso on me was warm, or even hot. There was her futilely cupped and sleeping hand; and here was her hair—long, straight, dark hair—some of it in my mouth and on my eyelids and tangled in my eyelashes and tickling my ears… Her head rested on my neck—and partly on my chin and lower cheek. I bent my lips sideways to kiss her hair and forehead experimentally. In those days, I often prayed usually for the will and stamina to see to it that an outcome to events did not come about only through my weaknesses. Now I prayed more questioningly: Is this going to come out okay? For me, for her—for long-term designs of history or Deity toward meaning. Give me a sign—if you can bear to. What does she want? (Ora.) Partly that meant what-did-she-intend…Her breath, her mouth—are a giant, fluttering moth—are an infant thing.

Me as waker and her sleeping, I was aware, tremendously, of the tremendous opposition between our states—it is almost as if we had two different kinds of flesh. Or money and fame as wakefulness and flesh as sleep…. And then the thought past the one of Dear God, I don’t understand my life, to the sense that truth and a book were all very well but reality was real. This wasn’t as simple-minded as it sounds since I’d been advised, perhaps dishonestly, of one’s greatness, so to speak…

There is a lot to be found in this deeply private, relatively plain-spoken nocturnal meditation. Three strains of thought are closely woven together, with sensual desire as a ground bass, with religious misgivings, with doubts about the personal relation mixed with misgivings about literary success. A reader cannot doubt the immediacy of the thoughts; on the other hand the reader cannot know how sharp is the comment when Wiley stops his admiring inspection of Ora in mid-sentence to remember that some kids in college once admired his own Wileyesque rib cage. The half-deprecatory “if you prefer” calls attention to the Brodkey uncertainty principle, as does the concluding “so to speak.” (The addition of “been” to that last sentence seems grammatically imperative.) On the other hand, not all the resources of the English tongue can mitigate the ungainly embarrassment of that expression “one’s greatness, so to speak.”

Particularly puzzling are the unexpressed connectives in the next-to-last paragraph. Perhaps it is God who is asked to “give him a sign” whether things will come out okay, but what reason is there to think that He will speak through the mouth of the sleeping Ora? The great fluttering moth is a thoroughly indefinite symbol, and that her breath, her mouth are an infant thing is the ultimate in nonspecification. Perhaps she is a speechless child, an expiring spirit, a vampire, or a psyche; the reader may pick among these alternatives, or make up his own.

A fiction intent on following out the author’s private trains of association, and relatively indifferent to the effects they may create in the reader, plays for high stakes. The associated imagery that the writer spins out may reverberate on the deepest layers of the reader’s spiritual being, or alternatively may fall flat and lie as dead words on the page. No doubt a more imaginative and perceptive reader will follow the strains of imagery with more sympathy and at least an analogous understanding. But no reader can hope to bring to imaginative writing the same measure of indirection and overtone that the writer himself possessed. Sooner or later rarefied associative writing must seem to have diminished its audience to a possible readership of one. Brodkey is naturally a diffuse writer, and he draws out his impressionistic imaginings sometimes to irritating length. On the other hand, it’s always possible for the reader to pass over sections of language that he finds unduly obtuse, picking up again when the road becomes less rocky; this is particularly likely to happen in a book of over eight hundred pages. But the process of mounting and dismounting is bound to diffuse and distract the reader’s attention.

A convenient way to sample the Brodkey style and mannerisms before settling down to the long haul is by reading as a separate unit the two chapters devoted to Leonie in the last quarter of the book. This section returns us unexpectedly to a St. Louis milieu and a fourteen-year-old Wiley. The reader may find his own reasons for the hero’s late return to adolescence and the provinces—indeed, he will have to do so since the author provides no explanations at all. But the meanness of the scene, the inconclusiveness of the action, and the tangled erotic interests of the participants give rise in Wiley’s account to immense and violent imagery that makes use of dialects that are intermittently elusive and gross, metaphysical, banal, and powerfully expressive precisely because they don’t always make smooth discursive “sense.”

Here, for instance, are Wiley and Leonie, just introduced, settling down rather cold-bloodedly to a long exploratory session of messing around. The flow of thought is mostly that of Wiley-at-the-moment, though sometimes he stands outside himself (observing “the boy”), sometimes he addresses the reader directly as “you,” while the vocabulary slips from the semiclinical to the careless and kiddish.

Early phallicism.

It was locally conceivable—as dirty—with underneath stuff about death and war (around here) influencing people’s lives. I was interested in this stuff. I was someone half-girlish now but at a crossroads and about to be a man—maybe. So to whatever extent she was like me, she could imagine a man’s reality sprouting from her…her becoming a man…sort of….

This between her and me was a success thing but dark—and it felt deep and drowny, exhilarating, weird…like being in waves…deep water. I’m in deep—no safety—silent feelings. The kind of tone her lips had—what was conveyed in the touch of her lips in the so-called kiss—was that she was thinking about herself and she was kissing me.

She placated the boy with a certain notable potency of temporary affection…not an overwhelming weight of it. She wasn’t the testing kind—the kind that tested you with finality and huge hints of fucking. The first kisses only lightly—tactfully, cutely—touched on the scandal of my being male, if I can say it like that. I felt a little bit kidnapped by feelings. My lips and her lips, her voice and my voice were silenced except in kissing and in the feelings aroused by kissing—you crawl into the small, damp, shadowy tunnel of this stuff…the conduit of other stuff that moves toward you and in you until, in a sense, you are professionally male although as a beginner in the black tunnel of the moment at the edge of an obscure future…

There is a lot here that one can’t understand because it hasn’t been expressed but that can be imaginatively felt at least in part because it is apparently beyond expression. These indirections have to be somehow grasped before one can approach a sense of Brodkey’s book “as a whole.”

“As a whole” may of course be the last way to consider The Runaway Soul; it can also be taken as a medley of Balkanized writings, a set of lectures, confessions, explorations, and masquerades, various as a good minestrone. It will not have symphonic coherence, but the reader, accepting the book as “variations on some themes,” will find in it both tests of his adaptive powers and a rising sense of exhilaration.

This Issue

November 21, 1991