In response to:

Apes and Us: An Exchange from the October 10, 1991 issue

To the Editors:

Philip Lieberman writes [Letters, NYR, October 10] that he objects only to “biologically implausible formulations” of Universal Grammar “that do not take account of genetic variability.” In response, Lord Zuckerman observes correctly that it is a “truism” that a “genetically based ‘universal grammer’ ” will be subject to variability. It remains only to add that the truism has always been regarded as exactly that.

Lieberman states that “until the past year, virtually all theoretical linguists working in the Chomskian tradition claimed that Universal Grammar was identical in all humans,” thus denying the truism. By “the past year,” he apparently has in mind Myrna Gopnick’s results, which he cites, on syntactic deficits. The claim that Lieberman attributes to “virtually all theoretical linguists…” is new to me; to my knowledge, Gopnick’s results, far from causing deep consternation, were welcomed as interesting evidence for what had been assumed. Perhaps Lieberman has been misled by the standard assumption that for some task at hand—say, the study of some aspect of language structure, use, or acquisition—we can safely abstract from possible variation. To quote almost at random, “invariability across the species” is a “simplifying assumption” that “seems to provide a close approximation to the facts” and is, “so far as we know, fair enough” for particular inquiries (Chomsky, Reflections on Language, 1975). Note that one who takes the trouble to understand what is always assumed might argue that this approximation is not good enough, and that problems might be solved by moving beyond it. A serious proposal to that effect would, again, be welcomed, another truism.

Lieberman’s other attributions are no less fanciful, and at this level of unseriousness, not worth pursuing.

Noam Chomsky

MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Lord Zuckerman replies:

Truism or not, it is salutary that Chomsky should remind us that variability is an inevitable consequence of sexual reproduction, and that what he terms a universal grammar can be no exception, whatever its genetic basis. Whether Lieberman or any other scholar will ever be able to provide a precise answer to Bickerton’s further question—are man’s syntactical abilities due to one set of interacting genes or to more than one—is another matter and anyone’s guess. So, to return to one of the issues which I discussed in my review, I cannot conceive that the genetic basis of the rigid and unchanging pattern of calls and signs that characterize communication in species of monkey and ape can be the same as that which underlies the syntactic power that provides us with the flexibility to use our ever-growing vocabulary to generate an infinity of meanings.

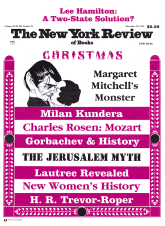

This Issue

December 19, 1991