1.

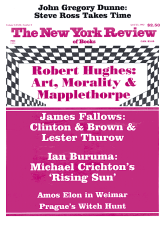

I mean to ramble over matters of art and morality, censorship, politics, and public institutions. And to make things worse I am going to start with an event which is certainly emblematic, but which you may have heard altogether too much about already—namely, the scandal over Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs a couple of years back.

To me, the interest of the Mapplethorpe affair lies in its stark display of colliding American values—but not much else. Despite the enthusiasm of his fans, I have never been able to think of him as a major photographer. I first visited his New York studio in 1970; at the time his work, such as it was, consisted of fetishistic but banal collages of beefcake photos with the addition of things like a leopardskin jockstrap or a gauze patch with a pus stain on it. If you had told me, as I was going down the stairs forty minutes later, that this small talent would be as famous as Jackson Pollock within twenty years, and that the scandal produced by his work would threaten the equilibrium of the whole relationship between museums and government in America, I would have said you were crazy.

I saw quite a lot of his work, though not of Mapplethorpe himself, over the ensuing years: the heavy, brutal S&M images of the X portfolio, the elegant overpresented photos of Lisa Lyons, the icy male nudes in homage to Horst and Baron von Gloeden, the Edward Weston flowers. It was the work of a man who knew the history of photographs, for whom the camera was an instrument of quotation; the mannered, postmodern chic of his images was then, sometimes, slammed back into a dreadful immediacy by the pornographic violence of the subject matter. But I don’t think chic is a value, and I felt at odds with the culture of affectless quotation that had taken over New York art, and my notions of sexual bliss did not coincide with Mapplethorpe’s; and so when he asked me to write a catalog introduction to his show—the show that caused all the trouble—I had to tell him that since the X portfolio was obviously the key to his work and constituted his main claim to originality, and since I found the images of sexual torture in it too disgusting to write about with enthusiasm, he had better find someone else. Which he did. Several, in fact.

Now most of us know, at least in outline, what happened to Mapplethorpe’s retrospective in 1988–1990. It was shown at the Whitney Museum in New York to scenes of enthusiasm rivaling the palmiest moments of his mentor, Andy Warhol, and then, under the title The Perfect Moment, without the slightest incident at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. But when the show was about to appear at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, it came under heavy attack from conservatives on the ground that the display was partially underwritten by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and that the government had no right to be spending taxpayers’ money on supporting work so repugnant to the general moral sensibility of the American public.

The sum involved was $40,000, representing one fiftieth of 1 percent of a copper penny for every man, woman, and child in America; but still, as Hilton Kramer and others were at pains to point out, it was public money all the same.

The main spokesman was that tribune of the people Senator Jesse Helms, and when the dewlaps of his wrath started shaking outside the Corcoran, the curators caved in and canceled the show. Helms and other conservatives, including Orrin Hatch, then tried to push an amendment through the Senate preventing the NEA from underwriting filth and blasphemy again. The measure was defeated by seventy-three votes to twenty-four; wisely, the Senate decided that the definition of pornography should be left to the courts. And into court it went. The Mapplethorpe show moved on to Cincinnati, where the conservatives decided to make a test case out of it, arraigning the director of the Contemporary Arts Center for public obscenity.

There was much pessimistic hand wringing in the art world over what would happen when the X portfolio was shown to a bunch of, well, rubes in the Midwest. But once again a kind of natural American common sense, maybe more common in Cincinnati than in Soho, prevailed. Largely because the prosecution could not find any credible expert witnesses against the work, the director was acquitted and the Mapplethorpe circus rolled on; the dead photographer was by now either a culture hero or a culture demon; but either way, everyone from Maine to Albuquerque had heard of him, and the net economic result of Senator Helms’s objurgations had been to push the prices of X portfolio prints from about $10,000 to somewhere around $100,000.

Advertisement

But the Mapplethorpe debacle had two broad cultural results. First, it caused paranoia in the relations between American museums and their funding sources. It produced an atmosphere of doubt, self-censorship, and disoriented caution among curators and museum directors when it came to raising money and facing the political demands of pressure groups.

This crisis shows no sign of going away; in fact, in an election year, it only gets worse. Clearly, and depending on IQ, the agenda of American conservatives is either to destroy the National Endowment for the Arts or to restrict its benefactions to purely “mainstream” events. The latter seems more likely, given political realities: too many rich Republicans (and Democrats too of course) have a stake in the kind of prestige that cultural good works confer in their home cities—such as support of the local museum or symphony orchestra—to allow the NEA to perish altogether. Nevertheless, it is symptomatic of the present panic over state cultural funding that a coarse hack-journalist like Patrick Buchanan, not so much neoconservative as neolithic in his cultural views, could have forced George Bush to fire the head of the NEA, John Frohnmayer, in order to appease the know-nothings and fag-bashers on his right.

And second, it marked the demise of American aestheticism, and revealed the bankruptcy of the culture of therapeutics which had come to dominate the way so many cultural professionals in this country were apt to argue the relations between art and its public. To argue what I mean I am going to have to leave Mapplethorpe, leave our fin de siècle, and circle back to a much earlier time.

Senator Helms and his allies on the fundamentalist religious right had gone after Mapplethorpe—and Andres Serrano, too, and others—for two basic reasons. The first was opportunistic: the need to establish themselves as defenders of the American Way, now that their original crusade against the Red Menace had been rendered null and void by the end of the cold war and the general collapse of communism. Having lost the barbarian at the gates, they went for the fairy at the bottom of the garden. But the second reason was that they felt art ought to be morally and spiritually uplifting, therapeutic, a bit like religion. Americans do seem to feel, on some basic level, that the main justification for art is its therapeutic power. That is the basis on which the museums of America have presented themselves to the public ever since they began in the nineteenth century—education, benefit, spiritual uplift, and not just enjoyment or the recording of cultural history. Its roots are entwined with America’s sense of cultural identity as it developed between about 1830 and the Civil War. But they reach down to an earlier soil, that of Puritanism. If we are going to understand what happened at the end of the Eighties we have to go back to the very foundations of Protestant America, and not in some facile spirit of ridiculing the Puritan either.

The men and women of seventeenth-century New England didn’t have much time for the visual arts. Painting and sculpture were spiritual snares, best left to the Catholics. Their great source of aesthetic satisfaction was the Word, the logos.

In their sermons you glimpse the preoccupations of a later America: the sense of nature as the sign of God’s presence in the world, and the special mission of American nature to be this sign and to serve as the metaphor of the good society, new but everlasting, precarious but fruitful. Here is Samuel Sewall, preaching in Massachusetts in 1697, handing down the covenant:

As long as Plum Island shall faithfully keep the appointed post, notwithstanding all the hectoring words and hard blows of the proud and boisterous ocean; as long as any salmon, or sturgeon, shall swim in the streams of Merrimack,…as long as any Cattle be fed with the grass growing in the meadows, which do humbly bow themselves down before Turkey Hill; as long as any free and harmless Doves shall find a white oak within the township, to perch, or feed, or build a careless nest upon…as long as Nature shall not grow old and dote, but shall constantly remember to give the rows of Indian corn their education, by pairs:—so long shall Christians be born here; and being first made to meet, shall from thence be translated, to be made partakers of the Saints in Light.

Words like Sewall’s still have immense resonance for us today. The perception of redemptive nature, which would suffuse nineteenth-century American painting and reach a climax in our time with the environmental movement, was right there in America from the beginning.

Advertisement

There was as yet no art in America that could rival the spiritual consolations of nature, or be invested with nature’s moral power. Almost all Americans before 1820 breathed a very thin aesthetic air. They were short of good, let alone great, art and architecture to look at. We tend to forget, when we visit the period rooms of American museums and admire the fine furniture in them, that the general aesthetic atmosphere of the early republic was much more like Dogpatch. Most Americans saw no monumental sculpture; few great churches, and none on a European scale of effort and craft; no Colosseums or Pantheons; and as yet, no museums. And everything was new. The public monuments of American classicism, like Jefferson’s State Capitol in Virginia, were islands in a sea of far humbler buildings. Average Americans lived not in nice houses with foundations and porches and maybe pediments, still less in permanent edifices of stone or brick, but in makeshift wooden structures that were the ancestors of today’s trailer home, only far worse built.

American beauty resided much more in nature than in culture. Thus the intelligent American, if he or she got the chance to visit Europe, could find his taste transformed in a sort of pentecostal flash by a single monument of antiquity, as Jefferson’s was by the sight of the Maison Carrée at Nîmes, the Roman temple that created his conception of public architecture. One hour with the Medici Venus in Florence or the Apollo Belvedere in the Vatican could outweigh all one’s past aesthetic experience as the raw child of the new republic. One’s own experience endowed the English or European work with a stupendous authority.

Today, with mass tourism and mass reproduction to cushion the shock in advance, it is more difficult for us to imagine that state of mind. An American arriving in Europe had no preparation, except maybe from some inaccurate prints, for what he was about to see. To the culturally starved Yankee the arrival in Italy or France seemed like an admission to Heaven, a place reached after an initiation of suffering, the purgatorial voyage across the Atlantic. Four weeks of vomiting, and then…Chartres. “We do not dream,” one New Yorker wrote in 1845, “of the new sense which is developed by the sight of a masterpiece. It is as though we had always lived in a world where our eyes, though open, saw but a blank, and were then brought into another, where they were saluted by grace and beauty.”

To this frame of mind was added a very important component: a general admiration, among the thin ranks of American art lovers, for John Ruskin, whose work began to appear here after 1845. Ruskin never went to America, but he cast a powerful spell over its art values: you might say that his rolling, supple, irresistible prose afforded the link between (on one hand) the rich ground of religious oratory inherited from the Puritans, and (on the other) the way mid-century Americans were schooling themselves to think about the visual arts and what role they ought to play in a democracy. To overcome Puritan resistance to artificial richness and the sensuous ordering of sight, one had to stress—indeed, wildly exaggerate—the moralizing power of art. You cast your reflections on exalted emotion in religious terms: benefit, conversion, refinement, unification.

Particularly since quite a number of the writers were ministers themselves. On their modest tours of Europe they felt art overwhelming them with proof that man was made in God’s image, that the soul was immortal, and above all that man-made beauty was part of God’s inbuilt design for moral instruction. When Henry Ward Beecher, the top pulpit speaker of his day, went to France to see the cultural sights he spoke of “instant conversion,” not mere enjoyment or edification. Of course, one had to choose. One did not like, for instance, Brueghel and Teniers, with all their gorging and puking peasants. One felt somewhat uneasy at the fleshy Madonnas of Titian. Too much model, not enough Virgin. The truly elevating artists were Fra Angelico, the blessed monk of Florence, and of course Raphael. The desire to bring back authoritative spiritual icons of memory naturally condemned the American visitor to disappointment, some of the time. Beecher’s sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, “positively ran,” as she recounts it, into the Louvre to find pictures “that would seize and control my whole being. But for such I looked in vain. Most of the men there had painted with dry eyes and cool hearts, thinking little of heroism, faith, love or immortality.” The real artist, she went on, went without explanation straight to the heart; his work was not an acquired taste; one did not need to learn to read it.

The idea that it was within the power of the visual arts to change the moral dimension of life reached its peak between the death of Monroe and that of Lincoln. One sees it in full bloom in the weekly editorials of The Crayon, New York’s main art magazine in the 1850s. It was the voice of the American artist’s profession and, as such, held strong views on artists’ character and conduct. As the editor bluntly put it in 1855, “The enjoyment of beauty is dependent on, and in ratio with, the moral excellence of the individual. We have assumed that Art is an elevating power, that it has in itself a spirit of morality.” The first form of the American artist as culture hero, then, is a preacher. He raised art from being mere craft by moral utterance. God was the supreme artist; they imitated His work, the “Book of Nature.” They divided the light and calmed the waters—especially if they were Boston Luminists. They were a counterweight to American materialism.

What was art for? The Crayon asked, in what it called “this hard, angular and grovelling age,” the 1850s. Why, it was to show the artist as “a reformer, a philanthropist, full of hope and reverence and love.” And if he slipped, he fell a long way, like Lucifer. “If the reverence of men is to be given to Art,” warned another editorial, “especial care must be taken that it is not…offered in foul and unseemly vessels. We judge religion by the character of its priesthood and we would do well to judge art by the character of those who represent and embody it.” One can almost hear the shade of the late Robert Mapplethorpe rustling its leather wings in mirth.

But this proposition, one may be fairly sure, would have been news to most artists—let alone patrons—of the Renaissance. Nobody has ever denied that Sigismondo Malatesta, the Lord of Rimini, had excellent taste. He hired the most refined of quattrocento architects, Leon Battista Alberti, to design a memorial temple to his wife, and then got the sculptor Agostino di Duccio to decorate it, and retained Piero della Francesca to paint it. Yet Sigismondo was a man of such callousness and rapacity that he was known in his life as Il Lupo, the Wolf, and so execrated after his death that the Catholic church made him (for a time) the only man apart from Judas Iscariot officially listed as being in Hell—a distinction he earned by trussing up a papal emissary, the fifteen-year-old Bishop of Fano, in his own rochet and publicly sodomizing him before his applauding army in the main square of Rimini.

That is not the way trustees of major American cultural institutions are expected to behave. We know, in our heart of hearts, that the idea that people are morally ennobled by contact with works of art is a pious fiction. Some collectors are noble, philanthropic, and educated; others are swindling boors who would still think Parmigianino was a kind of cheese if they didn’t have the boys at Christie’s to set them straight. Museums have been sustained by some of the best and most disinterested people in America, like Duncan Phillips or Paul Mellon; and by some of the worst, like the late Armand Hammer. There is just no generalizing about the moral effects of art, because it doesn’t seem to have any. If it did, people who are constantly exposed to it, including all curators and critics, would be saints, and we are not.

Under the influence of the Romantic movement, the desire for art as religion changed; it was gradually supplanted by a taste for the romantic sublime, still morally instructive, but more indefinite and secular. The Hudson River painters created their images of American nature as God’s fingerprint; Frederick Church and Albert Bierstadt made immense landscapes that gave Americans all the traits of Romantic art—size, virtuosity, surrender to prodigy and spectacle—except for one: its anxiety. The American wilderness, in their hands, never makes you feel insecure. It is Eden; its God is an American god whose gospel is Manifest Destiny. It is not the world of Turner of Géricault, with its intimations of disaster and death. Nor is it the field of experience that some American writing had claimed—Melville’s sense of the catastrophic, or Poe’s morbid self-enclosure. It is pious, public, and full of uplift.

No wonder it was so popular with the growing American art audience in the 1870s and 1880s. For this audience expected art to grant it relief from the dark side of life. It didn’t like either Romantic anguish or realism. There is a strange absence from American painting at this time, like the dog that didn’t bark in the night. It is the refusal to deal in any explicit way with the immense social trauma of the Civil War. American art, apart from illustration, hardly mentions the war at all. The sense of pity, fratricidal horror, and social waste that pervades the writing of the time—Walt Whitman, for example—and is still surfacing thirty years later in Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage, is only to be seen in arranged battlefield photographs like those of Matthew Brady—never in painting. This is a curious outcome, particularly if you believe, as I do, that the best strand in nineteenth-century American art is not so much the Romantic-nationalist one of Bierstadt and Church, as the line of virile, empirical sight that runs from Audubon through Eakins and Homer.

By the 1880s the function of art as quasi-religious uplift was beginning to modulate into a still more secular form, that of art as therapy, personal or social. This deeply affected the character of that special cultural form, the American museum. By now, in its great and growing prosperity, America wanted museums. But they would be different from European ones. They would not, for instance, be stores of imperial plunder, like the British Museum or the Louvre. (Actually, immense quantities of stuff were ripped off from the native Indians and the cultures south of the Rio Grande, but we call this anthropology, not plunder.) They would not be state-run or, except marginally, state-funded. Because state funding, in a democracy, means tax—and since one of the founding myths of America was a tax revolt, the Boston Tea Party, the idea of paying taxes to support culture has never caught on here. Other countries have come, with many a weary groan, to accept the principle that there is no civilization without taxation. Not America, where the annual budget of the National Endowment for the Arts is still around 10 percent of the $1.6 billion the French government set aside for cultural projects in fiscal 1991, and less than our governmental expenditure on military marching bands.

Here, museums would grow from the voluntary decision of the rich to create zones of transcendence within the society; they would share the cultural wealth with a public that couldn’t own it. For as the historian Jackson Lears has pointed out in his excellent study of American culture at the nineteenth century’s end, No Place of Grace, it is quite wrong to suppose that the Robber Barons (and Baronesses) who were busy applying the immense suction of their capital to the art reserves of old Europe were doing so from simple greed. Investment hardly figured in their calculations at all—this wasn’t the 1980s. Some of them, notably Charles Freer and Isabella Stewart Gardner, were deeply neurasthenic creatures who looked at art to cure their nervous afflictions and thought it could do the same for the less well-off. The public museum would soothe the working man—and woman too. The great art of the past would alleviate their resentments. William James put his finger on this in 1903, after he went to the public opening of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s private museum in Boston, Fenway Court. He compared it to a clinic. Visiting such a place, he wrote, would give harried self-conscious Americans the chance to forget themselves, to become like children again, immersed in wonder.

The idea that publicly accessible art would help dispel social resentment lay close to the heart of the American museum enterprise. In Europe they thought, Well, we already have all these paintings and drawings and sculpture, now let’s do something with them, put them in museums. In America they thought, We don’t have anything, no art comes with the territory of American identity, so let’s acquire art purposively, make it part of what we want to do with a democratic society. We’ll refine ourselves along with others. The European museum was by no means indifferent to public education, but the American museum was much more actively concerned with it.

The search for the masterpiece was a vehicle of reconciliation. No other country had sharper cultural contrasts. On one hand, the raw, booming, ruthless, Promethean nature of American capitalism, with the possibility of class war always waiting in the wings. On the other, the idealized past—a past not America’s own, but now vicariously within its reach, the Middle Ages and Renaissance that Bernard Berenson and Joseph Duveen were selling to the rich of Boston, Chicago, New York. These were locked together, because one provided relief from the anxieties of the other. Profiting from the Dynamo, Americans now turned to the Virgin; and, as Dorothy Parker jotted in the visitor’s book of San Simeon after noticing a Della Robbia over the entrance to Marion Davies’s bedroom:

Upon my honor, I saw a Madonna

Standing in a niche

Above the door of the private whore

Of the world’s worst son of a bitch.

America’s search for signs of spiritual value in art was not confined to the European Renaissance. It embraced Japan and China too; hence the powerful effect of the so-called Boston bonzes like William Bigelow and Ernest Fenollosa, whose collecting efforts in Japan in search of their own satori would give Boston its unrivaled collection of Japanese art in the 1890s, a time when the Japanese themselves were shedding it under the early stress of Westernization.

And this emphasis on the therapeutic increased greatly after 1920, between the Armory Show and the time when modernism really started becoming the institutional culture of America. If cultivated American taste resisted modernism at first, it was as much as anything because, in its disjunctiveness and apparent violence to pictorial norms, it didn’t seem spiritual enough. Could it deliver on the inherited promise of art, to provide avenues of transcendental escape from the harsh environment of industrial modernity? Could you reconcile the Ancients and the Moderns?

The museum answer, right from the moment the Museum of Modern Art was founded, was “yes.” The American museum had to balance its sober nature against the basic claim of the modernist avant-garde, which is that art advances by injecting doses of unacceptability into its own discourse, thus opening new possibilities of culture. The result was a brilliant adaptation, unheard of in Europe. America came up with the idea of therapeutic avant-gardism, and built museums in its name. These temples stood on two pillars. The first was aestheticism, or art for art’s sake, which decreed that all works of art should be read first in terms of their formal properties: this freed the artwork from Puritan censure. The second was the familiar one of social benefit: though art for art’s sake was right to put them outside the frame of moral judgment, works of art were moral in themselves because, whether you knew it or not at first, they pointed the way to higher truths and so did you good. You might be offended at first but then you would adjust, and culture would keep on advancing.

2.

Which brings us back to Robert Mapplethorpe’s X portfolio, there in the museum. For the truly amazing thing about the defenses that art writers made for these scenes of sexual torture is how they were all couched in terms either of an aestheticism that was so solipsistic as to be absurd, or else of labored and unverifiable claims to therapeutic benefit. The first effort depends on a willingness to drag form and content apart that is, quite simply, over the moon. An old acquaintance of mine, dead now, used to relate how she once went in a group around the National Gallery in London led by Roger Fry, the English formalist critic. He stopped to analyze a triptych by Orcagna, in which God the Father, terrible in his wrath, flashing eyes and streaming beard, is pointing implacably to his sacrificed Son. “And now,” Fry would say, “we must turn our attention to the dominant central mass.”

Now, seventy years later, one gets a critic like Janet Kardon, in the Mapplethorpe catalog and in her testimony in the Cincinnati trial, reflecting on one photo of a man’s fist up his partner’s rectum, and another of a finger rammed into a penis, and fluting on about “the centrality of the forearm” and how it anchors the composition, and how “the scenes appear to be distilled from real life,” and how their formal arrangement “purifies, even cancels, the prurient elements.” This, I would say, is the kind of exhausted and literally de-moralized aestheticism that would find no basic difference between a Nuremberg rally and Busby Berkeley spectacular, since both, after all, are example of Art Deco choreography.

But it is no worse than the diametrically opposite view, advanced by such writers as Ingrid Sischy and Kay Larson—that such images as those in the X portfolio are didactic: they teach us moral lessons, stripping away the veils of prudery and ignorance and thus promoting gay rights by confronting us with the outer limits of human sexual behavior, beyond which only death is possible. This, wrote Larson, is “the last frontier of self-liberation and freedom.” The man with his genitals on the whipping block becomes the hip version of the Edwardian mountaineer, dangling from some Himalayan crag: below him the void, around him the rope, and the peak experience above.

I find this dubious, to put it mildly. If a museum showed images of such things happening to consenting, masochistic women, there would be an uproar of protest from within the art world: sexism, degradation, exploitation, the lot. What is sauce for the goose is, or should be, sauce for the gander. And in any case, as Rochelle Gurstein recently pointed out in an excellent piece in Tikkun, the Mapplethorpe affair reveals

how many cultural arbiters, like many political theorists, are straitjacketed by a mode of discourse that narrowly conceives of disputes over what should appear in public in terms of individual rights—in this case the artist’s right of expression—rather than in terms that address the public’s interest in the quality and character of our modern world.

I would defend the exhibition of the X portfolio on First Amendment grounds, as long as it’s restricted to consenting adults. But we fool ourselves if we suppose the First Amendment exhausts the terms of the debate, or if we go along with the idea that all taboos on sexual representation are made to be broken, and that breaking them has some vital relationship with the importance of art, now, in 1992.

I have dwelt on the hullaballoo over a part of the work of one overrated American photographer because it feeds directly into the issue of politics in art, and how American museums treat it. It seems to me that there is absolutely no reason why a museum, any museum, should favor art which is overtly political over art which is not. Today’s political art is only a coda to the idea that painting and sculpture can provoke social change.

Throughout the whole history of the avant-garde, this hope has been refuted by experience. No work of art in the twentieth century has even had the kind of impact that Uncle Tom’s Cabin did on the way Americans thought about slavery, or The Gulag Archipelago did on illusions about the real nature of communism. The most celebrated, widely reproduced, and universally recognizable political painting of the twentieth century is Guernica, and it didn’t change Franco’s regime one inch or shorten his life by so much as one day. What really changes political opinion is events, argument, press photographs, and TV.

The catalog convention of the Nineties is to dwell on activist artists “addressing issues” of racism, sexism, AIDS, and so forth. But an artist’s merits are not a function of his or her gender, ideology, sexual preference, skin color, or medical condition, and to address an issue is not necessarily to address a public. The HIV virus isn’t listening. Joe Sixpack isn’t looking at the virtuous feminist knockoffs of John Heartfield on the Whitney wall—he’s got a Playmate taped on the sheetrock next to the bandsaw, and all the Barbara Krugers in the world aren’t going to get him or anyone else to mend his ways.

The political art we have in postmodernist America is one long exercise in preaching to the converted. As Adam Gopnik pointed out in The New Yorker recently, when reviewing the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, it consists basically of taking an unexceptionable if obvious idea—“racism is wrong”—or “New York shouldn’t have thousands of beggars and lunatics on the street”—then coding it so obliquely that when the viewer has retranslated it he feels the glow of being included in what we call the “discourse” of the artworld. But the fact that a work of art is about AIDS or bigotry no more endows it with aesthetic merit than the fact that it’s about mermaids and palm trees.

Throughout the Eighties, for instance, the Whitney Museum took most of its curatorial orders from the market. Now, to judge from the last Biennial, it takes its cues from PC. The Biennial catalog introduction, bursting with received ideas, was entitled “Culture Under Siege”; it lamented the orgy of the past eight years while tactfully omitting any mention of how the Whitney had hosted it. Sackcloth and ashes are to this museum in the Nineties what ladies’ cartridge belts were to Bloomingdale’s in the early Seventies, an act of taste.

But not much of one, because so much of the new activist art is so badly made that only its context—its presence in a museum—suggests that it has any aesthetic intention. I know that such an objection cuts no ice with many people: merely to ask that a work of art be well made is, to them, a sign of elitism, and presumably some critics would theorize that a badly made work of art is only a metaphor of how ratty the rest of the world of production has become, now that the ethic of craftsmanship has largely disappeared, so that artistic ineptitude thrust into the museum context has acquired some kind of critical function. But that’s not what one really thought when looking at the stuff in the Biennial: a sprawling, dull piece of documentation like a school pinboard project by Group Material called Aids Timeline, for instance, or a work by Jessica Diamond consisting of an equals sign canceled out with a cross, underneath which was lettered in a feeble script, “Totally Unequal.” Anyone who thinks that this plaintive diagram contributes anything fresh to one’s grasp of privilege in America, merely by virtue of getting some wall space in a museum, is dreaming.

Europe in the last few years has produced a few artists of real dignity, complexity, and imaginative power whose work you could call political—Anselm Kiefer, for instance, or Christian Boltanski. But the abiding traits of American victim art are posturing and ineptitude. In the performances of Karen Finley and Holly Hughes you get the extreme of what can go wrong with art-as-politics—the belief that mere expressiveness is enough; that I become an artist by showing you my warm guts and defying you to reject them. You don’t like my guts? You and Jesse Helms, fella.

The claims of this stuff are infantile. I have demands, I have needs. Why have you not gratified them? The “you” allows no differentiation, and the self-righteousness of the “I” is deeply anaesthetic. One would be glad of some sign of awareness of the nuance that distinguished art from slogans. This has been the minimal requirement of good political art, and especially of satire, from the time of Gillray and Goya and Géricault through that of Picasso and Diego Rivera. But today the stress is on the merely personal, the “expressive.” Satire is distrusted as elitist. Hence the discipline of art, indicated by a love of structure, clarity, complexity, nuance, and imaginative ambition, recedes; and claims to exemption come forward. I am a victim: How dare you impose your aesthetic standards on me? Don’t you see that you have damaged me so badly that I need only display my wounds and call it art? Last year there appeared in Art in America a gem of an interview with Karen Finley, in which this ex-Catholic performance artist declared that the measure of her oppression as a woman was that she had no opportunity, no chance whatsoever, of becoming Pope. And she meant it.

One could hardly find a more vivid epitome of the self-absorption of the artist-as-victim. I am an ex-Catholic myself, and the thought of this injustice struck a chord in me. But mulling it over, I came to see that there is, in fact, a reason why Karen Finley should be ineligible for the papacy. The Pope is only infallible part of the time, when he is speaking ex cathedra on matters of faith and morals. The radical performance artist, in her full status as victim, is infallible all the time. And no institution, not even one as old and cunning as the Catholic Church, could bear the grave weight of continuous infallibility in its leader. This, even more than the prospect of a chocolate-coated Irishwoman whining about oppression on the Fisherman’s Throne, is why I should vote against her if I were a member of the College of Cardinals, which I am not likely to be either.

The pressures of activism are putting a strain on museums, as they are meant to do, and they are very quickly internalized by the staff. Two systems of preference about art come into play, and they produce a double censoriousness.

A dramatic example of this happened in Washington last year. In April, the National Museum of American Art put on an exhibition called The West as America, a huge anthology of images meant to revise the triumphalist version of the white settlement of America in the nineteenth century. What did the painters and sculptors of the time tell us about Manifest Destiny? The show began with history paintings of the Pilgrim Fathers and ended with photos of Californian redwoods with roads cut through their trunks. It was quite frank about choosing works of art as evidence of ideas and opinions, and as records of events, rather than for their intrinsic aesthetic merits. Nothing wrong with that, as long as you make it clear what you’re doing, which the curators did. Often quite minor, or aesthetically negligible, or even repellent works of art will tell you a lot about social assumptions. And “masterpieces” are thin on the ground in nineteenth-century American painting anyhow. What one saw, for the most part, was the earnest efforts of small provincial talents whose work would hardly be worth studying except for the clarity with which it set out the themes of an expansionist America. The show set out to deconstruct images, and this too was fair enough, since if anything in this culture was ever constructed, it is the foundation myth of the American West.

I thought it was an interesting and stimulating show, and said so in a review. What I did not like so much were the catalog and, especially, the wall labels, which were suffused with late-Marxist, lumpen-feminist diatribes. These labels used to be a great feature of Russian museums. “This Fabergé egg, symbol of the frivolous decadence of the Romanoffs,…” and so forth. They have vanished from Russia, and migrated here. Here, folks, is a picture of a Huron. Lo, the poor Native American! See, he is depicted as dying! And note the subservient posture of the squaw, an attempt to project the phallocentricity of primitive capitalism onto conquered races! And the broken arrow on the ground, emblem of his lost though no doubt conventionally exaggerated potency! Next slide! One of the catalog authors even turned her attention to the frames around the pictures, claiming that “rectilinear frames…provide a dramatic demonstration of white power and control.” A little of this goes a long way, and The West as America had a lot of it.

Nevertheless I was amazed by the vehemence of the reaction to the show. Starting with Daniel Boorstin, the former librarian of Congress, a crowd of politicos and right-wing columnists put on their boots and started kicking. It occurred to none of them that the legendary history of the American West had been under attack from social historians for years, and that the argument of the museum’s show was neither unprecedented nor particularly new, except insofar as it was transferred into the field of art. Nor did they think it proper that the John Wayne version of the frontier should be questioned at all. And of course the wall labels played right into their hands. The charge was led by Senator Ted Stevens of Alaska, a Republican pipeliner who had his own reasons for not wanting the Smithsonian to put on shows of what he called “perverted history,” which mentioned conquest, development, and the fate of Indians. He accused the secretary of the Smithsonian of “having a political agenda,” as though he himself did not.

So the message was clear enough: We’ll be back, get into line or we’ll cut your funds off. This message has filled the ears of American institutions ever since the Mapplethorpe mess. And so the director of the National Museum of American Art, Elizabeth Broun, received quite a lot of good will from critics, museum professionals, and the like: The West as America wasn’t a perfect show, it had defects of rhetoric, but it posed real questions about the uses and meanings of American art and seemed, on balance, well worth doing. And in any case, my enemy’s enemy is my friend.

But no sooner had Ms. Broun emerged from the murk of right-wing censoriousness than she decided to do a little censoring herself. The month after the West show closed, the National Museum of American Art opened another exhibit, organized by another museum and traveling to Washington, which contained a work by the noted American minimalist Sol Le Witt. Le Witt is mainly known for his modular grids, but this work was an early one from the 1960s—a box into which one looked at images, repetitious serial enlargements of a fullfrontal photo of a naked woman. In a transport of political correctness Ms. Broun decided that Mr. Le Witt was causing the viewer to focus in a prurient and sexist manner on the lady’s public hair, and forthwith banned the work from the show. Blam!—straight in the foot. The curator who’d put the Le Witt in there in the first place immediately set up a press campaign against Ms. Broun’s act of censorship; the work was put back in the show. Having squandered all the art world good will that the attacks on the West show had created for her, Ms. Broun limped off to remove the slug from her instep, vowing, I’ve no doubt, like Senator Stevens to be back. Good censorship—no, let us call it “intervention-based affirmative sensitivity”—is therapeutic and redounds to the advantage of women and minorities. Bad censorship is what the pale penis people do to you. Here endeth the lesson.

Am I alone in finding something rather narrow-minded and stultifying about this? Clearly not: political pressures have in the last few years become a grim encumbrance for American museums, and a topic of obsessive worry for their professional staff. There is a right jaw of the vise, and a left one, and between the two the museum is painfully squeezed and may in the end be distorted out of useful shape. These pressures are far more extreme in the United States than in any European country I know of. They are the result of a totalization of political influence, a belief—common to both left and right—that no sphere of public culture should be exempt from political pressure, since everything in it supposedly boils down to politics anyway. This is the outcome both of the PC belief that the personal is the political, acts of imagination not exempted, and of the conservative view that any stick that you can beat liberals with is a good stick, and never mind what else gets flattened in the struggle. The American museum was never designed to be an arena for such disputes, and it is proving decidedly awkward and even inept at responding to them. And its response is complicated by the claims of activist art to constitute an avant-garde.

For the last quarter century it has been obvious that the idea of an avant-garde corresponds to no cultural reality in America. Its myth, that of the innovative artist or group struggling against an entrenched establishment, is dead. Why? Because new art has formed our official culture ever since we can remember. America is addicted to progress; it loves the new as impartially as it loves the old. Hence the idea of an avant-garde could only survive here as a fiction, supported by devotional tales of cultural martyrdom; the context of these tales has now moved from style to gender and race, but the plot remains much the same. Today, nobody uses the term “avant-garde” anymore—it’s a nonword. Instead, dealers and curators say “cutting edge,” which still conveys the warmly positivist impression of hot new stuff slicing through the reactionary opposition, leaving the old stuff behind, shaping something, forging ahead.

Unfortunately this model broke in the Eighties and cannot be revived. The idea of therapeutic soulcraft through art sank when the art world became the art industry, when the greed and glitz of the Reagan era started riding on that “cutting edge,” when thousands of speculators got into the market and the junk-bond mentality hit contemporary art. As the art world filled up with sanctimonious folk who under other circumstances would have been selling swamp in Florida or snake oil in Texas, the more elevated its language became. Every asset stripper with a Salle on his wall could prattle knowingly of hyperreality and commodification. You cannot have an orgy like the one in the Eighties without a hangover, and now we have a big one. The population of the art world expanded enormously in the Eighties, thanks to overproduction of art school degrees in the Seventies and the sudden lure of the market. No conceivable base of collectors was large enough to support them, not even in the seven fat years that ended with the art market crash of 1990, let alone in the lean years that presumably lie ahead. Since the decay of American art education has been steady for the last three decades, most of them, like most people who do creative writing courses, are ill-trained and unlikely to produce anything memorable.

It’s not their fault: the art education system let them down by promoting theory over skill, therapy over apprenticeship, strategies over basics. In an overpopulated art world with a depressed market, you are going to hear more and more about how artists are discriminated against—endless complaints about racism, sexism, and so on; whereas the real problem is that there are too many artists for the base to support. There are probably 200,000 artists in America, and assuming that each of them makes forty works of art a year, that yields eight million objects, most of which don’t have a ghost of a chance of survival. Maybe what we need is a revival of the WPA projects of the 1930s, not that there’s the slightest likelihood of that. But certainly most of this surplus and homeless work isn’t going to find a home in the museum.

The sense of disenfranchisement among artists has led to a stream of attacks on the idea of “quality,” as though it were the enemy of justice. These, above all, the serious museum must resist. We have seen what they have done to academic literary studies. Quality, the argument goes, is a plot. It is the result of a conspiracy of white males to marginalize the work of other races and cultures. To invoke its presence in works of art is somehow inherently repressive.

Now you can’t deny that, at any time in the history of art, there have been inflated reputations and wrongly ignored artists. That happens in the short term, but in the long term the injustices tend to be corrected. There remains, I should say, much less institutional bias against women artists in America or against women writers or editors in American publishing. Against blacks there may be more, but even that is rapidly fading. Part of the hangover of the Eighties, however, is the vertigo that comes when you start to suspect how many of the eagles of the time were turkeys. The cultural feeding frenzy was hard on artists who develop slowly, on those who value a certain classical reticence and a precise accountancy of feeling over mere expressiveness or contestation. It also presented difficulties for those who believe that art based on the internal traditions of painting and sculpture may achieve values which simply aren’t accessible to art based on mass media. In some ways, such people face barriers of taste and museum practice today that are quite as formidable as the crust of received ideas a century ago.

But it is in the nature of human beings to discriminate. We make choices and judgments every day. These choices are part of real experience. They are influenced by others, of course, but they are not fundamentally the result of a passive reaction to authority. And we know that one of the realest experiences in cultural life is that of inequality between books and musical performances and paintings and other works of art. Some things do strike us as better than others—more articulate, more radiant with consciousness. We may have difficulty saying why, but the experience remains. The pleasure principle is enormously important in art, and those who would like to see it downgraded in favor of ideological utterance remind me of the English puritans who opposed bear baiting, not because it gave pain to the bear, but because it gave pleasure to the spectators.

For instance, my hobby is carpentry. I am fair at it—for an amateur. That is to say, I can make a drawer that slides, and do kitchen cabinets to a tolerance of about 3/32 of an inch, not good enough to be really good, but fair. I love the tools, the smell of shavings, the rhythm of work. I know that when I look at a Hepplewhite cabinet in a museum, or a frame house in Sag Harbor, I can read it—figure its construction, appreciate it skills—better than if I had never worked wood myself. But I also know that the dead hands that made the breakfront or the porch were far better than mine; they ran finer moldings, they knew about expansion, and their veneer didn’t have bumps. And when I see the level of woodworking in a Japanese structure like the great temple of Horyu-ji, the precision of the complex joints, the understanding of hinoki cypress as a live substance, I know that I couldn’t do anything like that if I had my whole life to live over. People who can make such things are an elite; they have earned the right to be. Does this fill me, the woodbutcher whose joints meet at eighty-nine or ninety-one degrees, with resentment? Absolutely not. Reverence and pleasure, more like.

Mutatis mutandis, it’s the same in writing and in the visual arts. You learn to discriminate. Not all cats are the same in the light. After a while you can see, for instance, why a drawing by Pater or Lancret might be different from one of exactly the same subject by Watteau: less tension in the line, a bit of fudging and fussing, and so on. This corresponds to experience, just as our perception and comparison of grace in the work of a basketball player or a tennis pro rises from experience. These differences of intensity, meaning, grace can’t be set forth in a little catechism or a recipe book. They can only be experienced and argued, and then seen in relation to a history that includes social history. If the museum provides the ground for this, it is doing its job. If it does not—and one of the ways of not doing it is to get distracted by problems of displaced ideology—then it is likely to fail, no matter how warm a glow of passing relevance it may feel. Likewise, museum people serve not only the public but the artist, whether that artist’s work is in the collection or not, by a scrupulous adherence to high artistic and intellectual standards. This discipline is not quantifiable, but it is or should be disinterested, and there are two sure ways to wreck it. One is to let the art market dictate its values to the museum. The other is to convert it into an arena of politics. Only if it resists both can the museum continue with its task of helping us discover a great but always partially lost civilization: our own.

This Issue

April 23, 1992