In the Republic of the Congo (Brazzaville), a syncretic religion has arisen around a cult of General Charles de Gaulle. Its altars are decorated with Crosses of Lorraine and large “V’s” for victory. Its followers sing and dance to invoke Ngolo, which is also the word for power in the Bakongo language.

Although the canonization of De Gaulle now underway in France has utterly different outward trappings, it is no less authentic, as any tourist can see who contemplates the vast concrete Cross of Lorraine, built in 1980, that rises from a hilltop near De Gaulle’s country house at Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises (Haute-Marne), over a small museum and souvenir stand.

The change has been profound. Thirty years ago, when De Gaulle was president of France, almost half of French citizens regularly voted against him, and the most violent among them—the hard-core militants of French Algeria—were trying to kill him. Less murderous but still unreconciled were most of the left, the remaining partisans of the Vichy regime of 1940–1944, supporters of an integrated Europe along the lines preached by Jean Monnet, and believers in French membership in an Atlantic alliance headed by the United States.

Today De Gaulle’s popular image is being reconstructed in ways that do considerable violence to history. On the left, Regis Debray, former companion of Che Guevara, has written a paean to the general.

Jean Lacouture, the sympathetic biographer of Léon Blum, Pierre Mendès France, François Mauriac, Nasser, and Ho Chi Minh, and a correspondent for Le Monde, who was far from enthusiastic when De Gaulle returned to power in 1958, has mellowed, too.

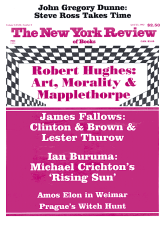

This Issue

April 23, 1992

-

1

A demain De Gaulle (Paris: Gallimard, 1990).

↩ -

2

Lacouture’s earlier De Gaulle (London: Hutchinson, 1970) was more critical than the present work.

↩ -

3

The Australian journalist Brian Crozier made this bizarre case in De Gaulle (Scribner’s, 1973).

↩ -

4

The classic analysis of De Gaulle’s leadership remains Inge and Stanley Hoffmann’s “De Gaulle as Political Artist: The Will to Grandeur,” in Stanley Hoffmann, Decline or Renewal? France Since the 1930s (Viking, 1974).

↩ -

5

Richard H. Ullmann, “The Covert French Connection,” Foreign Policy No. 75 (Summer 1989), pp. 3–33.

↩