Once in a while—in America perhaps more than once in a while—a book comes along whose interest is chiefly in the hype attending it. Rising Sun is such a book. The text of the publicity handout announced that this “explosive new thriller [was] rushed to publication one month earlier than previously announced because of its extraordinary timeliness with regard to US–Japan relations.”

This is unusual: thrillers are not generally rushed out to match political events. Odder still is the sheaf of newspaper clippings about the decline of American industries and the predatory methods of Japanese corporations stapled onto the advance reader’s edition. Singular, too, is the bibliography at the end of the book, listing mostly academic works on Japan, but also, for example, Donald Richie’s study of Kurosawa’s movies. Strangest of all, however, is Crichton’s afterword, which ends with a homily: “The Japanese are not our saviors. They are our competitors. We should not forget it.”

With such a buildup, the literary press could not be left behind. On the front page of The New York Times Book Review the thriller was compared to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for stirring up “the volcanic subtexts of our daily life.”1 Kirkus Reviews promised the return of the “Yellow Menace,” only now “he wears a three-piece suit and aims to dominate America through force of finance, not arms.”

Volcanic subtexts, Yellow Menace, Main Selection of the Book-of-the-Month club, first printing 225,000 copies, top of the best-seller lists, a Hollywood picture in the works—what exactly is going on here?

Michael Crichton clearly wanted to do more than entertain with a murder mystery. He wrote his book, so he told The New York Times, “to make America wake up.” Now, on the whole, people who go around trying to wake us up, as though we were all asleep, oblivious to some apocalyptic Truth, tend to be boring, or mad—like those melancholy figures who wander about with signs announcing the end of the world.

Crichton’s book isn’t boring. He is good at snappy dialogue—though his copious use of Japanese is often incongruous and sometimes wrong—and he is a deft manipulator of suspense. And he takes great pains to avoid giving the impression that he is mad. Indeed, the whole idea of the newspaper clippings, the bibliography, the afterword, and so on, is to make sure we get the serious message buried in the “explosive new thriller.” He dislikes the term “Japan-bashing,” he says, because it threatens to move the US-Japan debate into “an area of un-reasonableness.” The thriller, by implication, is reasonable.

Well, I wonder. But before going on, perhaps I should mention the story, the vessel, as it were, for Crichton’s awakening message to the American nation. In brief, it is this: a large Japanese corporation called Nakamoto is celebrating the opening of its new US headquarters, the Nakamoto Tower in downtown LA. A beautiful young American woman—Caucasian, naturally—is murdered during the party. Investigations follow. The Japanese obstruct, the American police bumble, the Japanese corrupt, the Americans are corrupted, and only through the brilliance of a semi-retired detective called Connor, who speaks Japanese and knows the Japanese mind—who can see “behind the mask,” so to speak—is the case more or less solved. Along the way, we have some kinky sex—the Japanese, unlike us, have no guilt, you see—and a couple of spectacular suicides: a US senator, framed for the murder of the girl, shoots himself through the mouth, and a Japanese gets himself a concrete suit by jumping into wet cement from a considerable height.

Sex and violence aside, the story has two leitmotifs that are bound to appeal: the decline of America, our way of life, etc., and a clearly identifiable enemy. The first is constantly alluded to by characters in the story, as well as by the author himself. “Shit: we’re giving this country away,” says a crude cop. “They already own Los Angeles,” says a woman at a party (“laughing”). “Our country’s going to hell,” says a television journalist. “They own the government,” says the crude cop. “The end of America, buddy…”

“They” is of course the enemy, Japan. There is a great deal of talk about “they” in the book. The enemy is identified all right, but it has no face. It is present everywhere, manipulating us, corrupting us, in our offices, our newspapers, our government, our universities, and, who knows, perhaps soon on our beaches and our landing grounds. “They” have a mind, a mentality, but no characters, no ideas. The pervasive, manipulative, inscrutable, mysterious mind is never expressed openly or directly. It is masked by subterfuge. Nakamoto Corporation, we are told, “presents an impenetrable mask to the rest of the world.” One of the few Japanese with a name, though without much in the way of human personality, Mr. Ishigura, has a face, but: “His face was a mask.”

Advertisement

Masked minds and inscrutable cultures need to be decoded, hence the stock character in many colonial and tropical fantasies: the expert, the man who has the lingo and knows the native mind, the white hero dancing dangerously on the edge of going native himself. This role is performed by Connor, who knows his way around sushi bars and knows when to be polite and when to be firm. Firmness in his case means breaking into the rough language of Japanese gangster movies. But in a good mood, he will hold forth on the finer points of Japanese manners, why “they” behave as they do, and so on. Connor likes Japan, but never forgets that we are at war.

The other stock figure in war propaganda is the good enemy, who has crossed over to the side of the angels. In Japanese wartime movies this role was often played by the Japanese actress Li Ko Ran, later known, during her brief Hollywood career, as Shirley Yamaguchi. She was the Chinese beauty who invariably fell in love with the dashing and sincere Japanese soldier; a love that symbolized the glorious future in Asia under Japanese tutelage. In nineteenth-century anti-Semitic fiction it is the “good Jew,” such as the beautiful Miriam in Felix Dahn’s Fight for Rome (1876), who identifies wholly with the German tribe and hates the rootless and treacherous Jews.

In Rising Sun we have the beautiful Theresa Asakuma. Theresa works in a high-tech research lab, one of the last not to fall into Japanese hands, hence, I suppose, its dilapidated state. Theresa is happy to help Connor and his wholesome American sidekick, Lieutenant Pete Smith, the narrator who plays Doctor Watson to Connor’s Holmes. She is happy to help because she hates the Japanese.

The beautiful Theresa is a useful character, because she represents the perfect target for Japanese bigotry. Her father was a black GI, and she has a crippled arm. She grew up in a small Japanese town, where the tolerance for blacks and cripples was low. Her story offers an opportunity to expound a little on Japanese racism—even the notorious treatment of polluted outcasts, the burakumin, many of whom work in the leather trade, gets an airing. Not that any of this is implausible or wrong. Outsiders do have a hard time in Japan. But it functions as yet another stake driven through the heart of “they.” It is a bit like European or Japanese descriptions of America, in which every American is either a gangster, a redneck, or a poor black.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is actually the last book I would have thought of comparing to Rising Sun. I can think of two anti-Semitic works that are much closer in tone and imagery. One is Jew Süss, the German film, directed by Veit Harlan in 1940. The other is a Japanese pop best seller by Uno Masami about the Jewish conspiracy to dominate the world. It is entitled The Day the Dollar Becomes Paper: Why We Must Learn From Jewish Knowledge Now.2

Harlan’s version of Jew Süss (there were many versions) shows how peaceful, prosperous eighteenth-century Württemberg is almost destroyed by letting the Jews in. The vain and gullible Duke of Württemberg has virtually exhausted the state budget by indulging his taste for pomp and dancing girls. The Jew Süss-Oppenheimer contrives, by oily flattery and promises of bottomless riches, to persuade the Duke to let him take care of his finances. He also presses the Duke to allow the Jews to settle in his city. Soon they control everything through their evil manipulation. As a symbol of German humiliation the Jew has his wicked way with the country sheriff’s daughter. She commits suicide, the good people of Württemberg at last rise up against the Duke and his Jews, Oppenheimer is hanged, and the Jews are driven out of town. The message at the end of the film is that the burghers of Württemberg woke up to the danger in their midst and banished the Jews by law. This law should be upheld, not only for the sake of our generation, but for our children, our grandchildren, and so on forever and ever.

Uno Masami’s book is a collection of more or less mad conspiracy theories. Among the more outré ones is the notion that Roosevelt, scion of the well-known Dutch Jewish family, tricked Japan into going to war, so that the US, as a front for world Jewish interests, could save the Jews from Hitler. The basic premise of the book is a simple one: Jews control world public opinion by controlling the media. Jews have convinced the decent and gullible Japanese that Japan should be internationalist instead of looking after its national interests. Thus American Jews wrote the postwar Japanese constitution to make Japan impotent. Thus the Jewish-controlled press made the Japanese feel guilty about the war. Thus decent Japanese companies such as Mitsubishi or Fujitsu cannot compete with IBM, because IBM is controlled by Jewish interests which are out to dominate the world. One salient point about this lunacy is that, to the likes of Uno, Jewish and American interests are more or less interchangeable.

Advertisement

Michael Crichton’s thriller is not quite as zany as Uno’s tract, or quite as odious as Harlan’s Jew Süss. And to call his book racist is perhaps to miss the point. After all, as he told The New York Times, he likes Japan very much. He may have painted a picture of the Japanese as liars and cheats, but as Connor, the expert on the native mind, points out, that is only from our point of view, not theirs. No, the problem with Crichton is that, like Uno and the makers of Jew Süss, he has conceived a paranoid world, in which sincere, decent folks are being manipulated by sinister forces. These forces need not be from a different race. In a different era, they might have been Communist.

Paranoia can be based on half-truths. To say that the craziest red-baiters were paranoid is not to say that communism bore no threat. Just so, undeniable problems with Japan do not alter the fact that some of the wildest alarmists are a trifle unhinged. Crichton describes, again in Connor’s words, how the Japanese in America are part of a “shadow world….Most of the time you’re never aware of it. We live in our regular American world, walking on our American streets, and we never notice that right alongside our world is a second world.” Couple this to the refrain that “they own” our city, our government, our country, and one is not so very far removed from Veit Harlan’s Württemberg.

The metaphors are remarkably similar. Masks are a key image in Rising Sun and in Jew Süss. The idea in Jew Süss is to contrast an organic, decent, even somewhat slow-witted German community, rooted in its native clay, and the artificial, devious, clever floating world of the rootless Jews. The Duke of Württemberg is warned by one of his courtiers that the Jew is always masked. In both Crichton and Harlan, the enemy is pictured as omnipresent, omnipotent, and certainly more sophisticated. “The Jews are always so intelligent,” says an exasperated Württenberger. “Not intelligent, just shrewd,” answers another. As Richard Wagner liked to say, the Jew can only imitate, not create.

Connor, only a little ironically, calls America “an underdeveloped peasant country.” Compared to the Japanese, he says, we are incompetent. But on the other hand, of course, “they” have bought our universities, because, as an American scientist tells Connor, “they know—after all the bullshit stops—that they can’t innovate as well as we can.” Not intelligent, just shrewd.

In Jew Süss and in Rising Sun, we are shown how native institutions are slowly taken over by alien forces. Veit Harlan suggests this by using dissolves and music: the German motto on the Württemberg shield of arms dissolves into Hebrew; a Bach chorale gradually melts into the song of a cantor. In Rising Sun, as in Uno’s book, our press is infiltrated; one of “their” people is “planted” at the LA Times, no less. Another LA Times reporter, one of “ours,” explains the situation: “The American press reports the prevailing opinion. The prevailing opinion is the opinion of the group in power. The Japanese are now in power.”

At the beginning of Rising Sun, Connor rides an elevator in the Nakamoto Tower with some American cops. An electronic voice anounces the floors in Japanese. “Fuck,” says the cop, “if an elevator is going to talk, it should be English. This is still America.” “Just barely,” says Connor.

This kind of paranoia is more complex than mere xenophobia. It suggests a deep frustration. Again, Harlan’s film is instructive: the fiancé of the girl who falls prey to the wicked Jew’s designs is shown as an impotent man—handsome in a blond, romantic, German sort of way, but incapable. In the beginning of the film, the girl makes advances to him, but he fails to respond. The Jew succeeds, albeit violently, where the decent German fails. The enemy as a potent stud: this is how an American floozy in Crichton’s book describes her Japanese patrons: ” ‘A lot of them, they are so polite, so correct, but then they get turned on, they have this…this way…’ She broke off, shaking her head. ‘They’re strange people.’ ”

There runs a streak of masochism through all this. And, to be sure, it wouldn’t be the first time that American self-flagellation has sold many books. But there is also a hint of awe for the enemy, as though we would like to be more like “them.” In 1942, Hitler quoted “the British Jew Lord Disraeli” as the source of the idea that the racial problem was the key to world history. The anti-Semitic jurist Carl Schmitt had a picture of Disraeli above his desk.3 Uno Masami wants the Japanese to learn from the Jews, to learn how they maintained the purity, the virility, and the independence of their race.

It is striking how often the fiercest Western critics of Japan are the ones who most want to emulate Japanese ways: protectionism, industrial policies, order, discipline. Crichton, or, rather, Connor speaks about being at war with Japan, and at the same time repeats with admiration all the cliches of Japanese cultural chauvinists: how the Japanese people are “members of the same family, and they can communicate without words,” or how good the Japanese police are, because “for major crimes, convictions run ninety-nine percent.” Connor forgets, perhaps, that confessions are enough to convict in Japan, and that the Japanese police are rather good at getting confessions.

Could it be, then, that some Americans are feeling frustrated with the messiness of American democracy, with its many competing interests and its lack of strong central power; that people are getting tired of free-wheeling individualism and the hurly-burly marketplace; that they despair of all the immigrants, who barely speak English yet occupy American cities in their expanding shadow worlds; that, in other words, many Americans would secretly like to feel part of one family, with order imposed from above? If so, it would be a sad thing. For America, thus awakened, would stop being the country to which millions came to escape from just such tribal orders. And those millions included quite a few Japanese.

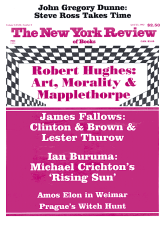

This Issue

April 23, 1992

-

1

Reviewed by Robert Nathan in the February 9 issue.

↩ -

2

Uno Masami, Doru ga Kami ni Naru Hi: Ima Koso Yudaya no Chisei ni Manabe (Tokyo: Bungei Shunju, 1987).

↩ -

3

For a detailed, quirky, and quite fascinating interpretation of Schmitt’s infatuation with Disraeli, see Nicolaus Sombart, Die Deutschen männer und ihre Feinde (Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag, 1991.)

↩