From my political ideals, it should be clear enough that I would like to accentuate culture in every possible way in my practice of politics. Culture in the widest possible sense of the word, including everything from what might be called the culture of everyday life—or “civility”—to what we know as high culture, including the arts and sciences.

I don’t mean that the state should heavily subsidize culture as a particular area of human endeavor, nor do I at all share the indignant fear of many artists that the period we are going through now is ruining culture and will eventually destroy it. Most of our artists have, unwittingly, grown accustomed to the unending generosity of the Socialist state. It subsidized a number of cultural institutions and offices, heedless of whether a film, say, cost one million or ten million crowns, or whether anyone ever went to see it. It didn’t matter how many idle actors the theaters had on their payrolls; the main thing was that everyone was on one, and thus on the take. The Communist state knew where the greatest danger to it lay: in the realm of the intellect and the spirit. It knew who first had to be pacified through irrational largesse. That the state was less and less successful at doing so is another matter, which merely confirms how right it was to be afraid; for, despite all the bribes and prizes and titles thrown their way, the artists were among the first to rebel.

This nostalgic complaint by artists who fondly remember their “social security” under socialism therefore leaves me unmoved. Culture must, in part at least, learn how to make its own way. It should be partially funded through tax write-offs, and through foundations, development funds, and the like—which, by the way, are forms that best suit its plurality and its freedom. The more varied the sources of funding for the arts and sciences, the greater variety and competition there will be in the arts and in scholarly research. The state should—in ways that are rational, open to scrutiny, and well thought out—support only those aspects of culture that are fundamental to our national identity and the civilized traditions of our land, and that can’t be conserved through market mechanisms alone. I am thinking of heritage sites (there can’t be a hotel in every castle or château to pay for its upkeep, nor can the old aristocracy be expected to return and provide for their upkeep merely to preserve family honor), libraries, museums, public archives, and such institutions, which today are in an appalling state of disrepair (as though the previous “regime of forgetting” deliberately set out to destroy these important witnesses to our past). Likewise, it is hard to imagine that the Church, or the churches, in the foreseeable future, will have the means to restore all the chapels, cathedrals, monasteries, and ecclesiastical buildings that have fallen into ruin over the forty years of communism. They are a part of the cultural wealth of the entire country, and not just the pride of the Church.

I mention all this only by way of introduction, for the sake of exactness. My main point is something else. I consider it immensely important that we concern ourselves with culture not just as one among many human activities, but in the broadest sense—the “culture of everything,” the general level of public manners. By that I mean chiefly the kind of relations that exist among people, between the powerful and the weak, the healthy and the sick, the young and the elderly, adults and children, business people and customers, men and women, teachers and students, officers and soldiers, policemen and citizens, and so on.

More than that, I am also thinking of the quality of people’s relationships to nature, to animals, to the atmosphere, to the landscape, to towns, to gardens, to their homes—the culture of housing and architecture, of public catering, of big business and small shops; the culture of work and advertising; the culture of fashion, behavior, and entertainment.

And there is even more: all this would be hard to imagine without a legal, political, and administrative culture, without the culture of relationships between the state and the citizen. Before the war, in all these areas, we were on the same level as the prosperous Western democracies of the day, if not higher. To assess our condition now, it’s enough to cross into Western Europe. I know that this catastrophic decline in the general cultural level, the level of public manners, is related to the decline in our economy, and is even, to a large degree, a direct consequence of it. Still, it frightens me more than economic decline does. It is more visible; it impinges on one more “physically,” as it were. I can well imagine that, as a citizen, it would bother me more if the pub I went to were a place where the customers spat on the floor and the staff behaved boorishly toward me than it would if I couldn’t afford to go there every day and order the most expensive meal on the menu. Likewise, it would bother me less not to be able to afford a family house than it would not to see any nice houses anywhere.

Advertisement

Perhaps what I’m trying to say is clear: however important it may be to get our economy back on its feet, it is far from being the only task facing us. It is no less important to do everything possible to improve the general cultural level of everyday life. As the economy develops, this will happen anyway. But we cannot depend on that alone. We must initiate a large-scale program for raising general cultural standards. And it is not true that we have to wait until we are rich to do this: we can begin at once, without a crown in our pockets. No one can persuade me that it takes a better-paid nurse to behave more considerately to a patient, that only an expensive house can be pleasing, that only a wealthy merchant can be courteous to his customers and display a handsome sign outside, that only a prosperous farmer can treat his livestock well. I would go even farther, and say that, in many respects, improving the civility of everyday life can accelerate economic development—from the culture of supply and demand, of trading and enterprise, right down to the culture of values and life style.

I want to do everything I can to contribute, in a specific way, to a program for raising the general level of civility, or at least everything I can to express my personal interest in such an improvement, whether I do so as president or not. I feel this is both an integral part and a logical consequence of my notion of politics as the practice of morality and application of a “higher responsibility.” After all, is there anything that citizens—and this is doubly true of politicians—should be more concerned about, ultimately, than trying to make life more pleasant, more interesting, more varied, and more bearable?

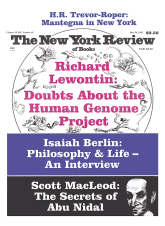

This Issue

May 28, 1992