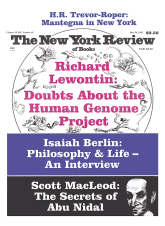

In 1786, on his famous Italian journey, Goethe came to Padua and visited the church of the Eremitani, the Hermit Friars. There he saw the frescoes by Mantegna, of the lives of Saint James and Saint Christopher, in the funerary chapel of Antonio degli Ovetari. He stood before them “astounded” at their scrupulous detail, their imaginative power, their strength and subtlety, and as he recorded it, a cascade of epithets tumbled from his pen. Here he had found one of “the older painters” who stood behind and inspired the great masters of the High Renaissance, enabling them to take off from earth toward heaven. “Thus did art develop after the ages of barbarism”: Mantegna pointed to Titian.

Not everyone would agree. To many critics, even if they admire his work, Mantegna fits uncomfortably, if at all, into a continuing tradition. Bernard Berenson, a classical spirit, was uncompromising. To him Mantegna was admirable only where he had learned from the Florentine artists who had come to Padua in his early days. For the rest, though saved by “the vigour and incorruptibility of his genius,” he was an “archaist,” a fifteenth-century Burne-Jones, whose work was “choked with unconsumed illustrative matter” and who “left no direct heirs”: the Florentines took over from the Florentines.

The argument continues today. Whereas Berenson censured Mantegna for failing to catch the true spirit of Antiquity, and describes him as purely pagan, without religious sense, Ronald Lightbown commends him for moving away from antiquarian study to grasp the principles of classical sculpture, “the lucidity, grace and serenity of antique art,” and Sir Ernst Gombrich finds in him “very little pagan sensuality,” and much Christian “devotion.” When such experts so differ, what can we do but echo the words of Sir Lawrence Gowing in the catalog: that Mantegna “is, no doubt, a prime exponent of something essential in the tradition—one of the great archetypes. But an exponent and an archetype of what?”

His biography at least is simple. He grew up in Padua, and it was there, in the workshop of Francesco Squarcione, the first and best known private art school in northern Italy, that he learned his technique and formed his ideas; there also that he became known to the antiquaries and scribes who frequented the place, to the humanist scholars of the university, and to the patrons who would commission his early works. Then, in 1460, having married the sister of Giovanni and Gentile Bellini, and emancipated himself (not without litigation) from the possessive Squarcione, who had become his adoptive father, he was lured away from Padua to Mantua. There, for the rest of his life—another forty-six years—he would be the court painter of three generations of the Gonzaga family, admired, indulged, but also effectively monopolized by them. It was only in 1466 that he was able, with their permission, to visit Florence, and only in 1488–1490 that he was allowed, as a special favor to the Pope, to travel to Rome and decorate the chapel of the new papal villa. Padua and Mantua were thus the two fixed centers of his life, the recipients of his work.

Today that work is scattered. The visitor to Padua cannot see the original frescoes which astounded Goethe: they were largely destroyed by a bomb in 1944; and in Mantua, although the great frescoes of the Painted Chamber, being unmovable and unbombed, are still there, all the other works painted for his princely patrons have long been dispersed: scattered in the great, scandalous sales of the Mantuan collections to Charles I and his agents in 1627 and 1628. However, an impressive number of them were reunited in the exhibition which was organized by Olivetti and the Royal Academy of London, and which is now at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. In it there are works sent from Amsterdam and Copenhagen, Berlin, Frankfurt, and Munich, Saõ Paolo, Montreal, and Malibu; but Padua and Mantua can supply only one item each: the former a detached fragment from the Ovetari chapel, the latter a work which has survived there because it was executed by Mantegna not for the Gonzaga but for himself: for his own funerary chapel in the Church of St. Andrea.

Mantegna owed much to Padua, both material and method. The material was the visible relics of Roman grandeur, which were to be seen there; the method was the recently discovered technique of perspective, which he would exploit in so disconcerting a way. Both these lessons were learned in the bottega of Squarcione. Squarcione may not have been a very good painter, but we are told that he taught perspective and that he had assembled in his shop, both locally and from his early travels in Greece, samples and fragments of Roman and Greco-Roman statues, friezes, sarcophagi, inscriptions, or casts of them, which he taught his pupils to imitate.

Advertisement

And they did imitate them. For we are now in the early fifteenth century, when the cult of Roman antiquity, Roman architecture, Roman literature—and even, behind it and through it, Greek architecture and Greek literature—had become the rage in Italy, and particularly in Padua. Padua might, by then, have lost its political independence—that is, it was no longer subject to the rule of the Carrara family; it might have become a mere provincial city in the Venetian republic. But (unlike Venice) it was a historic Roman—even, it was claimed, a mythical Trojan—city: the city of Livy, the historian of ancient Rome, whose alleged bones had recently been found there, the city in which Petrarch, the great prophet of the Roman revival, had spent his last years, revered as a mortal god. It was also (again unlike Venice) a university city, and its university—the state university of the republic—was famous, drawing on a wide catchment area: German and Hungarian scholars resorted to it. Meanwhile, in the agony of Byzantium, Greek scholars too were coming to Italy, Greek manuscripts were being transcribed, illuminated, translated. All this was important to artists. If the Christian myth—their main subject—were to be portrayed by them, it could be portrayed “historically” in an artificial recreation of its original context, the imperial Roman world.

The young Mantegna was fascinated by that world. Whatever his formal education, which can hardly have been profound—he was a carpenter’s son who entered the art school at ten—he was clearly precocious. His early work was admired, he was taken up by scholars, praised by poets, became a friend of humanists, scribes, illuminators. He was interested in letters and lettering, learned Latin, picked up, and would parade, a little Greek, and is credited with the illumination of at least one manuscript, which is in the exhibition: a Latin translation of Eusebius executed in Padua in 1450, when he was around twenty.

But more impressive than manuscripts were monuments. Mantegna was evidently in love with the monumentality of ancient Rome: too much in love, thought Squarcione, who (says Vasari), becoming jealous of him, criticized his work “in front of everyone,” attacking particularly his love of stone. “Stone, he said, was essentially a hard substance and could never convey the softness and tenderness of flesh and natural objects with their various movements and folds.” Mantegna would have done better, he said, simply to depict marble statues, “seeing that his pictures resembled ancient statues rather than living creatures.” This, says Vasari, enraged Mantegna and was one of the causes of the quarrel which led to their legal separation. It is a standard charge which cannot be entirely refuted: indeed it is explicitly repeated by Berenson when he says that Mantegna painted people “as if they were made of colored marble rather than of flesh and blood.”

Mantegna’s love of stone is not confined to its worked state, in sculpture and architecture. He loved it raw, too. In either state, it is the background, or foreground, to so many of his paintings. His characters look at us through a sculptural, sometimes illusionist, frame; Roman columns, arches, friezes, dominate the lives and martyrdoms of the saints; and then there are those wild, irregular rock formations, sometimes surrealist with their menacing cracks and bizarre stratification. Sometimes the rough and smooth are thrown together. The cavernous entrance to Hell is finished off with a Roman arch. Saint Sebastian receives his arrows tied to a Corinthian column attached to a broken arch, behind which a crowded architectural folly trembles on the overhanging lip of a beetling precipice.

In 1455, when he had finished the Ovetari frescoes, Mantegna was already famous in Padua, hailed by his humanist friends as the Apelles of his age. The term was conventional, if not meaningless, for no works of Apelles, the most famous of Greek painters, survive; but perhaps it was less meaningless when applied to him, for he really sought, through the means at his disposal—ancient ruins, classical texts, humanist commentaries—to re-create ancient art; and with his severe spirit, his scrupulous eye for detail, his virtuosity of perspective—he did create something and gave to those dry bones a mysterious new life. At any rate, those early frescoes made his name and freed him from bondage. In the last of them he inserted a portrait of his rejected “father” Squarcione, depicting him as an ugly, pot-bellied executioner; and by 1460, after two and a half years of procrastination, for he was now assured of patronage, he yielded to the persuasion of the Marchese Ludovico Gonzaga and moved from Padua to Mantua, from the birthplace of Livy to that of Virgil.

A short distance but a great change. Unlike Padua, Mantua had no impressive Roman remains, no real university, no professors; but it had a court and a prince; and the prince, though poor, was himself a humanist and his court one of the most cultivated in Italy. The Gonzaga, like most Italian princes, were upstarts, though legitimized by imperial authority: a condottiere family, who eked out their revenues by nicely calculated warfare on behalf of more powerful neighbors—Venice, Milan, Florence. But Ludovico’s father, Gianfrancesco, had brought to Mantua the most distinguished and successful of educators Vittorino da Feltre, whose pupils dominated the next reign, so that the whole court was permeated by humanism. Moreover, in 1459, Pius II, the humanist Pope, had called a council to Mantua in the hope (vain hope!) of mounting a crusade against the all-conquering Ottoman Turks, and so the city, for eight months, seemed the center of the world.

Advertisement

In the following years Ludovico converted Mantua into a splendid city. Streets were paved, printing was introduced, new industries arose. So did new palaces and churches, one of them designed by the greatest virtuoso of his time, L.B. Alberti, who dedicated his famous book On Painting to the Marchese. Other distinguished visitors came too: the Queen of Cyprus, the King of Denmark, and the German relations of the Wittelsbach Marchesa. With the help of his grand friends, the Marchese managed to secure a cardinalate for his sixteen-year-old son, Francesco, who, like him, was a pupil of Vittorino. In this civilized court Mantegna was appreciated and indulged, though he often taxed the patience of his patrons by his slowness—he was notoriously slow, a perfectionist—and some of his most famous works were produced to decorate their palaces and churches, old and new.

In particular two great series of paintings. First, the frescoes in the Camera Picta of the castle showing scenes of the princely family: the Marchese Ludovico and his wife Barbara of Bavaria, with their cardinal son and grand foreign friends and relations, including the King of Denmark and the Emperor, on whom they had waited in Italy, not to mention their dogs, all observed from above by putti and human and animal figures looking down from an illusory gallery in the ceiling, open to the sky—the first trompe l’oeil (we are told) on record. This series, done for Ludovico, is the only major work of Mantegna still wholly intact in its original setting.

Then there is that stupendous series, The Triumphs of Caesar, done for Ludovico’s grandson, Francesco, who was also a condottiere and made something of a cult of Caesar, as a martial (but more successful) predecessor. This, says Vasari, was Mantegna’s “best work ever”: nine huge canvases show the triumphal procession,

the ornate and beautiful chariot, the figure of a man cursing the victorious leader, the victor’s relations, the perfumes, incense and sacrifices, the priests, the bulls crowned for sacrifice, the prisoners, the booty captured by the troops, the elephants, the spoils, the victories…

In this spectacular work Mantegna deployed all his gifts: his historical and topographical erudition, even pedantry, and his most typical perspective trick, viewing the subject di in sù, so that it is raised above the eye level.

The Triumphs have had a history of their own. Being movable, unlike the frescoes, they have often been moved, first from place to place within the Gonzaga palaces, where they were put on show, then in that infamous sale, to London, for the collection of Charles I. After his execution they were exempted from the other infamous sales, which scattered that collection throughout Europe—it is said that the subject was as pleasing to Oliver Cromwell as it had been to the condottiere Francesco—and they have remained in England ever since as part of the royal collection at Hampton Court. They emerged for the exhibition at Burlington House, and formed the climax of it, in a room large enough to display the whole series. Alas, they can hardly be expected to appear in New York, being unfit for transatlantic travel: the journey to Burlington House was a unique, and sufficient, exposure.

In 1486, while Mantegna was working on the Triumphs of Caesar, the young marchese, Francesco Gonzaga, married Isabella d’Este, then aged sixteen. She had had a sound humanist education in Ferrara and was something of a bluestocking, eager to show that she kept up with the fashion. She was also an exacting patron, giving strict and detailed orders to artists and scholars. Her taste was for classical allegories with a high moral content, and Mantegna was required to satisfy it. Hence some of his latest subjects: Pallas Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue, The Fall of Ignorant Humanity, and the Parnassus. She also planned a statue of Virgil, to be set up in his birthplace, and Mantegna designed it; but no suitable sculptor could be found and it was never realized. A ruthless and acquisitive collector, Isabella drove hard bargains with Mantegna, as with everyone else, and when he was old and in debt exploited his misfortune to secure, at a knockdown price, a marble bust of a Roman matron, the most treasured item in his collection.

What kind of a man was this artist who has been so variously judged and who sits so uneasily in the artistic tradition? Many have found him disagreeable. He was quarrelsome and litigious; but so were many others in that competitive world. He was certainly ambitious, professionally and socially. When approached by the Gonzagas, he demanded the right to use their coat of arms. Later, he would be knighted by them and be made a count palatine (for what that was worth) by the Emperor. We are told that he and his brother-in-law Gentile Bellini were the first artists to seek such titles of honor. Though much admired, he was disliked by the other artists at the Gonzaga court, over whom he tyrannized, secure in the favor of the prince. He in turn believed that he was the victim of their envy, a genius frustrated by the machinations of smaller men. In his later works he dwelt on this theme: his frieze The Battle of the Sea Gods is evidently an allegory on the envy of artists, and his drawing The Calumny of Apelles barely needs a commentary. His bronze bust of himself, placed after his death in his funerary chapel (there is a colored plaster cast in the exhibition) does not portray a happy or a genial man. To Keith Christiansen of the Metropolitan Museum it presents “a Roman stoic philosopher, disdainful of the world”; to Lawrence Gowing, more positively, “stony hostility.”

However, there are lighter moments. To have attracted the praise of humanist poets and scholars at so early an age, Mantegna must have had social charm as well as genius and wit. With the Gonzaga family, who appreciated him and treated him generously in every way, he was obviously at ease: the spirit of the frescoes in the Camera Picta is unusually relaxed. The Cardinal Francesco, planning to take a cure at the baths of Porretta, near Bologna, asked for the company of Mantegna to entertain him by his agreeable conversation. And then there is that well-known episode, the outing on Lake Garda in 1464.

It was a party of four, all artists and scholars. They sailed in a boat festooned with greenery, from island to island, visiting churches and looking for Roman remains. To dignify the occasion, they gave themselves Roman titles: their leader, the painter Samuele da Tradate, was “emperor.” According to the antiquary Felice Feliciano, who wrote the account, he sat in the boat, crowned with myrtle, ivy, and periwinkle, and sang to his lute. Giovanni da Padova and Feliciano’s “incomparable friend” Mantegna were “consuls.” The jaunt, according to Feliciano’s record, was a great success. They discovered and copied inscriptions and identified “incontrovertibly” a temple of Diana, armed with her quiver, and “the other nymphs.” Then, disembarking in a quiet harbor, they entered a church and gave devout thanks to the Virgin and her Son for having inspired the happy idea of their seeing and admiring “the wonderful relics of [pagan] Antiquity.” This is not the usual picture that we have of Mantegna, but it is a welcome variation.

There are some gaps in the exhibition, which have been criticized. Some of Mantegna’s most admired paintings are absent: all three Saint Sebastians; the great altarpiece of San Zeno, Verona; the wonderfully (and inexactly) foreshortened Dead Christ in Milan. But what was originally planned was an exhibition of drawings and prints, so we should regard the paintings which were added as a bonus; but what a splendid bonus! Besides the Triumphs of Caesar some other works have not come from London to New York. They include the painting and several prints of the Descent into Limbo, a haunting work, and the marmoreal grisaille of Judith with the Head of Holofernes, now in Dublin. But as compensation New York will have two splendid portraits which were not shown in London. Both are of cardinals: one of the fresh-faced, innocent, teen-age Francesco Gonzaga, the other of Cardinal Trevisan, a tough and worldly prelate who not only collected books but also commanded fleets and armies: “a small dark and hairy man,” as a chronicler describes him, “very proud and grim,” who moved about “with a great escort of splendidly mounted horsemen.” How economically these two portraits capture the double face of the Catholic church in the age of the Renaissance!

This Issue

May 28, 1992