1.

Gaidar Aliyev was humiliated. After two decades as the Communist Party boss of Azerbaijan, he had been dumped in 1989 from Gorbachev’s Politburo, vilified for corruption in the news columns of Pravda, and reduced to sharing the back seat of a dismal Volga sedan with an American journalist. The pressures of Aliyev’s decline wore on him. He had suffered mild heart attacks; his complexion turned the shade of a votive candle. He complained of poverty to all who would listen. But Aliyev was still possessed of a certain unctuous charm, a parody of William Powell’s parody of a regal smoothie. “You should feel quite honored,” he told me as we drove to Moscow from his posh dacha in the village of Uspenskoye. “It’s not often that I give an audience.”

When he was a young man in Azerbaijan, Aliyev’s ambitions were almost derailed when he was accused of sexual assault. He avoided being thrown out of the Party by a single vote. There were no further “legal” proceedings. The Party’s judgment was all. In 1969, as the republic’s KGB Chief, Aliyev launched a “crusade against corruption,” but his crusade had no more moral content than John Gotti’s assault on Paul Castellano. Aliyev intended only to purge his enemies and elevate himself and his clan. At this, he succeeded spectacularly. Once installed as chief of the Azerbaijan Communist Party, Aliyev ruled the republic as surely as the Gambino family ran the ports of New York. The Caspian Sea caviar mafia, the Sumgait oil mafia, the fruits and vegetables mafia, the cotton mafia, the customs and transport mafias—they all reported to him, enriched him, worshiped him. Aliyev even dominated the intellectual life of Azerbaijan. He appointed his relatives chairmen of various institutes and academic departments, enabling them, in turn, to charge tens of thousands of rubles to scholars in search of meaningful employment.

The state structure in Azerbaijan—and everywhere else in the Soviet Union—could itself be called a mafia. The Communist Party was never a party in the Western sense, but rather a ruling elite that used terror and intimidation to appropriate the entire economic mechanism of a vast empire. Its rulers paid no more mind to the principles of political legitimacy than the dons of western Sicily. The analogy is imperfect but the Party was far closer to La Cosa Nostra than Il Partito Comunista Italiano. The Party’s dispensation of power and property was unchallenged by election or by law. Administrators of “socialist justice” were duplicitous props intended by the Party only to lend the appearance of civil society.

There had been, of course, some honest men in the Party structure. In one famous incident in Azerbaijan, a prosecutor named Gamboi Mamedov tried to investigate corruption in the Communist Party leadership. Aliyev had him fired and denounced. Later, at a session of the republican legislature, the inflamed Mamedov managed to grab the microphone, shouting, “The state plan is a swindle, likewise the budget—also, of course, those reports of economic success are a pack of lies, and…” Police hustled Mamedov off the speaker’s platform and into a back alley of obscurity. Seventeen loyal legislators quickly lined up to defend Aliyev. “Who are you fighting against, Gamboi?” Suleiman Ragimov, a hack writer and deputy, cried out. “God sent us his Son in the form of Gaidar Aliyev. Are you then opposing God?” The legislature rose as one in a standing ovation.

When Gorbachev came to power in 1985, he became the boss of bosses, the leader of a Communist Party Politburo in which most of the members were unabashed sultans, men like Aliyev of Azerbaijan, Viktor Grishin of Moscow, Grigori Romanov of Leningrad, Dinmukhamed Kunayev of Kazakhstan, Vladimir Shcherbitsky of Ukraine. The Central Committee, too, was filled with “dead souls,” hacks whose principal mission was the protection of the Party as a privileged caste. They had all long ago turned the poverty of Leninist ideology to their own advantage. In a state in which property belonged to all—in other words, to no one—the Communist Party owned everything, from the docks of Odessa to the orange trees of Georgia.

Aliyev, like the others, knew that the only imperative of stability under Brezhnev had been to grease the Don. Leonid Ilyich did not require the real prosperity or happiness of his people to please him. He needed only reports of same. So long as the official-looking documents that crossed his desk informed him of record successes and overfulfilled plans, he was well pleased.

Of course, the traditions of tribute pleased him even more. When Brezhnev came to the Azerbaijani capital, Baku, in 1978, Aliyev gave him a gold ring with a huge solitaire diamond, a hand-woven carpet so large it took up the train’s dining salon, and a portrait of the general secretary onto which rare gems had been pasted as “decoration.” For an official visit in 1982, Aliyev built a palace solely for Brezhnev’s use, a gaudy pile with all the kitsch grandeur of the Kennedy Center in Washington. The great man slept there for a couple of nights and then the palace closed. To commemorate the same visit, Aliyev gave Brezhnev a ring that symbolized the world view of the Kremlin better than any map. One huge jewel, representing Brezhnev the Sun King, was surrounded by fifteen smaller stones representing the fifteen union republics. “Like planets orbiting their sun,” as Aliyev explained. This masterpiece of the jeweler’s art was given the title “The Unbreakable Union of Republics of the Free.” When he received the ring and listened to Aliyev’s careful explication, Brezhnev, in full view of the television cameras, burst into tears of gratitude.

Advertisement

This system of shadows and gilt served the Party well while it lasted. But now Aliyev, who had grown accustomed to long Zil limousines while he was in power, found himself with his knees jammed into the seat ahead of him.

“Ach, I live badly,” he said as we sped along the highway. “My pension is tiny. Believe me, you would never work for such a sum. The driver? The car? Not mine. I just have the right to order them up once in a while.”

In office, Aliyev had grown used to ordering suits from the Kremlin tailor, to regular deliveries of Japanese electronics, American cigarettes, and delicacies from the “special farms” of the KGB. Now, in 1989, his world was confused and threatening. “Gorbachev says he is for the renovation of socialism and against capitalism,” Aliyev said. “Fine. But what sort of renovation? What does it mean? Is it social democracy? That’s not socialism. What exactly is his socialism? No one knows. They don’t know what socialism is anymore and they are all living in a fog. You Americans want everyone to follow your way, and the more things here are to the liking of George Bush, the better. But is Bush Jesus Christ or something?”

I assured him that Bush was less than that and we rode on a while in an agreeable silence toward Pushkin Square. Then, suddenly, through the evening fog, the gleaming apparition of the future: a pair of yellow arches, a winding line of hungry Russians. Aliyev sneered.

“McDonald’s!” he said. “There’s the perestroika you all love so much.”

2.

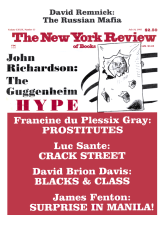

Although the new breed of private businessmen in Russia is rich with hustlers, thieves, racketeers, and confidence men, the collapse of the Communist Party apparatus was the dying day of the most gigantic mafia the world has ever known. From émigrés such as Konstantin Simis and Michael Voslensky, as well as from the Yugoslav Party dissident Milovan Djilas, we already understood something of the wholesale corruption and grotesque entitlements of the Communist Party.1 But now the best legal journalist in Russia, Arkady Vaksberg of the weekly Literaturnaya Gazeta, has produced a brilliant account of the salad days of the Mob state.

Vaksberg is a prominent figure in the Moscow liberal intelligentsia, but also well-connected, a lawyer and journalist skillful enough to have gained access to some of the most notorious figures in the leadership. Throughout the Brezhnev era, Vaksberg collected information on corruption, a subject as prohibited as any taken up by the dissidents. Although The Soviet Mafia is not supported by the level of notes and attribution to satisfy most scholarly or journalistic standards, Vaksberg’s portrait of the Party as an all-pervasive syndicate in what was once the Soviet Union rings absolutely true. His chapters on the Party’s criminal operations in Krasnodar, Sochi, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan describe the looting of a country, acts as cynical as Mobuto’s transfer of Zairian wealth into his personal Swiss accounts. After the August coup and the collapse of the Communist Party, events and the new evidence brought to light did nothing to contradict what Vaksberg had been writing in Literaturnaya Gazeta for years. The Party had so obviously socked away money abroad and sold off national resources—including the country’s vast gold reserves—that just after the coup collapsed and the Russian government sealed the Central Committee, the Party’s leading financial officer took a look into the future and threw himself off a high balcony to his death.

Above all, Vaksberg is at pains to make sure his foreign readers understand that Soviet corruption under Brezhnev was not a matter of exceptions, of rotten apples fouling the utopian barrel. No thorough prosecution of the Party’s corruption could stop with a single indictment. “If it were a question of just one of the former leaders, the new government could easily give him up to be destroyed, presenting him as the black sheep—a sad exception to the general rule,” Vaksberg writes. “But since it is a question precisely of all (or nearly all) of the members of the previous administration of autocratic old men, their exposure would lead to only one possible and inescapable conclusion from a historical perspective, that is, of the criminal character of the Party and the whole political system which enables criminals to make their way into positions of power and fanatically protects them from exposure.”

Advertisement

The Russian leadership is now faced with the political and moral dilemma of whether to issue indictments against Party leaders for corruption and plunder. Prosecutors want to know what happened to the gold reserves and foreign governments want badly to know what happened to billions of dollars in aid and loan guarantees that have simply “disappeared into a hole,” according to Gorbachev’s closest adviser, Alexander Yakovlev. But everyone is wary of criminal proceedings. There is no telling where it all would stop. Gorbachev himself anticipated this problem when, in the last days before his resignation, he asked Yeltsin privately to protect him from any future prosecution. Yeltsin first made his name as a Party rebel, but he, too, is reluctant to endorse a crusade that could easily widen into a witch hunt.

In many ways, Stalin’s terror mirrored the tactics of the mafia. He used terror as an instrument of coercion and discipline; he fostered an atmosphere of secrecy and universal suspicion; there were “made” men (Party apparatchiks) and the outward appearance of legitimate business (embassies, diplomats, trade, etc.).

As terror faded under Khrushchev and then Brezhnev, the Communist Party’s business became business. Sometimes “you gotta get rid of the bad blood,” Clemenza tells Michael Corleone in The Godfather. But after an all-out war, the mafia always dreams of an Arcadian period of cooperation, of relations that are profitable, stable, and, always, “just business.” Ideology in the post-Stalin era was not so much a system of beliefs or behavior as a kind of language, a password among the “made” men; if you could speak the language without deviation, you might be trusted to share in the loot. “More than anything else,” Djilas wrote a few years after Stalin’s death, “the essential aspect of contemporary communism is the new class of owners and exploiters.”

It was only in the post-Stalin era, after the violent period of collectivization and industrialization was over, that the Party’s mafia structures took shape. Vladimir Oleinik, a famously honest investigator in the Russian prosecutor’s office, published excerpts from his diary in Literaturnaya Gazeta that described the rapid growth in the 1960s of the trade mafia, a pyramid of payoffs that began in the Communist Party Central Committee and the top ministers and trickled down to butchers, bakers, and gravediggers, with everyone getting a piece. Oleinik told of how one Central Committee member filled his bank account by selling midlevel positions in the ministries for 50,000 rubles a spot.

The trade mafia worked thousands of scams. Even the small-time jobs had a certain beauty to them. On a trip to Central Asia, I was told about the “fruit juice scam.” Workers paid enormous bribes to get jobs servicing carbonated juice machines throughout the warm southern republics. When the workers serviced the machines, they skimped on the syrup and then sold the syrup elsewhere. They also skimmed some of the money out of the cash boxes. The workers used part of their gains to pay the foremen; the foreman, in turn, paid off the assistant minister; the assistant minister paid the minister, and all the way up the line to the top of the Party structure.

In the same region, high Party positions and awards were for sale. The magazine Smena reported that the position of regional Party secretary in Central Asia cost a bribe of over 100,000 rubles and an Order of Lenin, the Soviet Union equivalent of the Congressional Medal of Honor, cost anywhere from 100,000 rubles to 500,000 rubles.

It wasn’t as if this swamp of corruption was a secret to the Soviet people any more than the existence of the Mafia is a secret to the Palermo storekeeper forced to pay protection money. The mafia made itself known at every turn. You literally could not leave this earth without feeling the heavy hand of the mafia on your shoulder. One afternoon, the nanny who took care of our son came to work exhausted and depressed. Her mother had died, but what had run her down most was the enormous effort and expense of getting the woman buried—a process that drained her as much as it enriched the “cemetery mafia” and its Party patrons:

“Mother died, and I knew immediately this was going to run into big money for us,” Irina told me. “Soviet law guarantees that we all get a free funeral and burial. But that is a joke. The first stop was the bank. First, mother’s body had to be taken to the morgue. We were told that the morgues were all filled up, and they wouldn’t take her. But when we paid 200 rubles to the attendants, they took her. Then there was the 50 rubles for her shroud.

“Then the funeral agent said he had no coffins my mother’s size and that we could only buy something eight feet long. My mother was five feet tall. For 80 rubles he came up with the right size. Then the gravediggers said they could not dig the grave until 2 PM, even though the funeral was set for 10 AM. So that took two bottles of vodka and 25 rubles each. The driver of the funeral bus said he had another funeral that day and couldn’t take care of us. But for 30 rubles and a bottle of vodka we could solve the problem. We did. And so on with the grave site and the flowers and all the rest. In the end, it took 2,000 rubles to bury my mother—three months income for the family. Is that what ordinary life is supposed to be? To me, it’s like living by the law of the jungle.”

In the West, the mob historically moved in where there was no legal economy—in drugs, gambling, prostitution—and created a shadow economy. Sometimes, when it could buy the affections of a politician or two, the Mafia meddled in government contracts and ran protection schemes. But in the Soviet Union, Vaksberg makes clear, no economic transaction was untainted. It was as if the entire Soviet Union were ruled by a gigantic mob family known as the CPSU. Between an agricultural government minister’s order for, say, the production of ten tons of meat and Ivan Ivanov’s purchase of a kilo of veal for a family dinner, there were countless opportunities for mischief. No one could afford to avoid at least a certain degree of complicity. It was impossible to be honest. Even the Sakharov family, one supposes, bought on the black market once in a while. And all the baksheesh, eventually, filtered up through the vast economic hierarchy and enriched and strengthened the Communist Party.

“Look, it’s all very simple,” Andrei Fyodorov, who opened Moscow’s first cooperative restaurant in 1987, told me. “The mafia is the state itself.”

Before opening his restaurant, 36 Kropotkinskaya, Fyodorov worked for twenty-five years in the state restaurant business. Over a cup of tea one morning in his empty dining room, Fydorov described how it all worked at his old place of business, the Solnechny Restaurant, a huge state banquet hall. “The game started at nine o’clock on Friday mornings when the inspectors came by. I soon realized they were not really interested in the state of things in the restaurant. Very soon we established good contacts in terms of giving them various foodstuffs, providing tables in the restaurant, arranging saunas. The director of the restaurant would just tell me which services I had to arrange for them. You see, every person working in services is always on a hook. The restaurant director’s salary is 190 rubles a month, say. You can’t live on that, and so he is forced to take bribes. But there is a system of bribing in the USSR. You can’t get too greedy. A restaurant director cannot take more than 2,000 or 3,000 rubles per month. If he starts taking more, the system grows worried, and in the next five or six months new people will come around to inspect your place, which means that you can be arrested for violating the unwritten code of bribery.

“It goes from the bottom on up. From waiters, the bribes go to the maitre d’, and then on to the deputy director, to the director of the restaurant, and upward to various Party officials and auditing bodies. The same system applies to cafés, tailor shops, taxi depots, barbershops. A man who does not give bribes for more than six months is doomed.”

3.

Until his untimely arrest a few years ago, the most flamboyant Party-mafia figure in the country was Akhmadzhan Adylov, a “hero of socialist labor” who ran the rich Fergana Valley region of Uzbekistan for twenty years. Adylov was known as the Godfather and lived on a vast estate with peacocks, lions, thoroughbred horses, concubines, and a slave-labor force of thousands of men. Anywhere Adylov went, he was accompanied by his personal cooks and a mobile kitchen. For lunch, he always ate a roasted baby lamb. He locked his foes in a secret underground prison and tortured them when necessary. His favorite technique, Vaksberg reveals, was borrowed from the Nazis. In sub-zero temperatures, he would tie a man to a stake and spray him with cold water until he froze to death.

Adylov insisted he was a descendant of Tamerlane the Great. Considering his taste for ritual and cruelty, he may well have been. When a Party hack named Inamzhon Usmankhodzhaev was nominated for high office in Uzbekistan, he had to appear before Adylov for approval. As a test of loyalty, Vaksberg writes, Adylov ordered him to execute an informer but he could not bring himself to pull the trigger. Adylov could not excuse such a pathetic show of weakness and relented only when Usmankhodzhaev begged for forgiveness and, on his knees, licked clean the shoes of the Godfather.

From the Uzbeks, Brezhnev wanted only cotton and, more important, wonderful cotton statistics. The cotton scam was gigantic, yet elegant. Brezhnev would call on the “heroic peoples” of Uzbekistan to pick, say, twenty percent more cotton than the previous year. The workers, heroic as they were, could not possibly fulfill the order. (How could they when the previous year’s statistics were already wildly inflated?) But the republic’s Party leaders understood the greater reality of the situation. They assured Moscow that all had gone as planned. If not better! The central ministries in Moscow would, in turn, pay vast sums of rubles for the record crop. After paying the farms for what had actually been harvested, the republic’s leaders would pocket the surplus cash. Brezhnev, for his part, smacked his lips anticipating the gifts that would come, air freight, from Bukhara, Samarkand, and the other centers of Uzbekistan.

Of all the most famous Party mafias in the Soviet Union—the Kazakhs, the Azeris, the Georgians, the Crimeans, the Muscovites—the Uzbeks showed a certain flair. Sharaf Rashidov, the Uzbekistan Party chief, was a softspoken sybarite with literary pretensions. He fancied himself a novelist. To fulfill his ambition, he hired two Moscow hacks, Yuri Karasev and Boris Privalov, to do the writing. The resulting potboilers were published in editions that would cause Danielle Steele profound envy. Rashidov also knew how to satisfy his appetites. After hours of waving to the masses from the podium on May Day, he would descend into the podium basement where, as Vaksberg reports, there were tables “piled with festive fare and delightful young ladies ready to put the spring back in their step.” Rashidov was awarded ten Orders of Lenin and, when he died, he was buried with Pharaonic ceremony in the center of Tashkent near the Lenin Museum. For years, people brought mounds of roses and carnations to the tomb. Finally the Uzbek leaders recognized the shift in political winds from Moscow and moved the grave to a remote village. But Rashidov’s legacy lived on. In 1988, regional Party officials summarily pardoned 675 people who had been sentenced for their roles in the corruption scandals of the Brezhnev era.

These were the Go-Go Years and Uzbekistan did not, by any means, hold a monopoly on the grotesque. In the Krasnodar region of southern Russia, a mafia stronghold, ordinary membership in the Party cost anywhere from 3,000 to 6,000 rubles. Vyacheslav Voronkov, mayor of the resort city of Sochi, hired an Armenian architect to construct a musical fountain in the foyer of his state mansion. Tourists were permitted to pay a few kopecks to hear their Party leader’s fountain in full aria. When Communist Party chiefs in Russia went fishing, scuba divers plunged underwater and put fish on the hooks. When they went hunting, specially bred elk, stag, and deer were made to saunter across the field in point blank range. Everyone had a wonderful time. When the king of Afghanistan visited the Tadzhik resort of Tiger Gorge, he blew away the last Turan tiger in the country.

The mutual congratulations, the feasts and wedding parties, the piety and self-righteousness, all smacked of mafia culture. At a conference of the Soviet Writers’ Union in 1981, Yegor Ligachev, who would later serve as Gorbachev’s nominal number-two man and conservative nemesis, said, “You can’t imagine, comrades, what a joy it is for all of us to be able to get on with our work quietly and how well everything is going under the leadership of dear Leonid Ilyich. What a marvelous moral-political climate has been established in the Party and country with his coming to power! It is as if wings have sprouted on our backs, if you want to put it stylishly, like you writers do.”

In Kazakhstan, a republic bigger than all of western Europe, the Party chief, Dinmukhamed Kunayev, showed a certain kindliness to his relatives and (a rare feature in mafia men) to his wife. In The Soviet Mafia, Vaksberg confirms a story about the Kunayev household that I had first heard when I was in Alma-Ata.

It seems that Kunayev’s wife was jealous after learning that the wife of the Magadan Party secretary had been given as a gift an extremely expensive Japanese tea service. Magadan, a former labor camp center in the Far East, had unique access to Japanese goods, but Mrs. Kunayev would not be soothed. She had to have these cups and saucers. Party etiquette did not allow Kunayev simply to order the tea set from Japan or even Siberia. That was somehow too obvious. Even dispatching an aide to Tokyo was deemed unseemly.

“A way had to be found, of course,” Vaksberg writes. “And such was its originality and refinement that it deserves its own little page in the history of the Soviet mafia.”

Kunayev could not merely send his private plane, a Tupolev 134, on the mission. Party rules dictated that a Politburo member’s plane always had to be on the ready for emergency sessions in Moscow. So Kunayev told his aides to draw up an official report saying the plane’s engine required repair. This would allow him to order another plane while the first was being “fixed.”

Rules also dictated that after the repair, a Politburo member could not travel on the plane until it had been flown 20,000 kilometers. “The point of this brilliant move is clear,” Vaksberg writes. “Some of Kunaev’s closest associates were happy to take on the ‘kamikaze’ role. They worked out a route that, there and back, would clock up the required distance of 20,000 kilometers…. Everywhere they were received at the highest level—after all, they were emissaries from Kunaev himself. Those that have clawed their way to power have an astonishing passion for recording their pleasure on film. Thanks to this hobby we can today see with our own eyes how their trip went. Lavish picnics everywhere with the traditional shashlik and variety of vodkas, saunas and royal hunting of boar, elk and deer especially put up in front of them for easy shots…

“The first lady herself did not take the trip, needless to say. Like her husband, she was not allowed to take chances with her life. However, the jolly kamikazes came back with the passenger cabin and baggage hold crammed with gifts from the Soviet Far East and Siberia. They brought not only dozens of Japanese tea-sets but also Japanese sound and video equipment, furs, carvings on rare deer horn—the finest art of indigenous craftsmen—thousands of jars of Pacific crab and other fruits of the ocean. All these things were brought back to Alma-Ata like trophies.”

I went to Alma-Ata in hopes of meeting Kunayev. After three decades as the Kazakh Party chief, he had been forced to retire for “reasons of health” in 1986.

The first time I went to meet Kunayev, I tried to “doorstep” him, to show up at his house and hope for the best. This was not a wise maneuver. A KGB guard in the courtyard stopped me and made it clear, as his hand flashed lightly to his holster, that one further step toward the Kunayev residence would be inadvisable. So I tried a more conventional tack. Through a Kazakh journalist, a particularly obedient one whom I knew from Moscow, I asked to see Kunayev and sent along a list of innocuous questions of the “What are the key achievements of Kazakhstan under Soviet power?” variety. While we waited for word back from Kunayev, we ate a multi-course dinner at the apartment of the journalist’s in-laws. It was a long evening. His father-in-law got very drunk on the cognac I brought as a gift and he spoke lovingly for some hours of Stalin’s “iron hand.” We all ate heartily of a dish that I was later informed was “delicious noodles” mixed with shredded horses’ hearts. Tastes like chicken, my hosts assured me. They were wrong.

Finally, the call came from Kunayev. He was ready to see us the next morning at eleven.

We arrived, four of us, at the house five minutes early.

“Where are you going?” the guard asked us.

“We have an appointment with Kunayev.”

“Impossible,” the guard said.

“We do. An interview at eleven. He is expecting us.”

“Documents!”

We all showed our various papers and the guard went to his special phone. He talked for a while and came back smiling in triumph.

“The American is forbidden,” he said. This seemed non-negotiable.

I waited on the street. An hour later, the Kazakhs came out of Kunayev’s place, beaming. “Kunayev seemed sad that you couldn’t come,” one of them said. “He said, ‘It seems I’m powerless in my own house.”‘

It seemed I would never meet the fallen Don. But later the same day, during an interview with another Kazakh political official, one of the journalists walked into the room, tapped me on the shoulder, and told me to “wrap things up.” He had called Kunayev and we were all set to meet—on the street, outside the gates of the Communist Party’s House of Rest.

We raced to the spot in a taxi and waited. A half hour later, a Volga, not unlike Aliyev’s battered car, pulled up. Kunayev unfolded himself from the back seat. He was enormous, silver-haired, and dressed in a gangster’s chalk-striped suit. He wore dark glasses and carried an extremely authoritative walking stick. He had a fantastic smile, all bravado and condescension, the smile of a king. Without my asking a thing, he launched into a monologue about the such-and-such anniversary of Kazakhstan and wheat production and the need to preserve the monuments of the Bolshevik state. “I’ve never swayed,” he solemnly reminded us. “I am a man of the Leninist party line. Never forget that.” We swore we would not.

When I finally asked my earnest questions—about Gorbachev, about politics—Kunayev laughed them off, fiddled with the mahogany knob of his stick, and set back on the course of his monologue.

There were, I said interrupting, still many Kazakhs who wanted Kunayev to return to politics. “Are you ready to make a comeback?” I asked.

“I wouldn’t be against it,” he said. “Let the people decide. But tomorrow, I should tell you, I’m busy. I’m going hunting for ducks. I love hunting for ducks.”

4.

The decline of the Party mafia began with the death of Brezhnev and the brief reign of Yuri Andropov. In one sense, Andropov was a terrible man, a beast. No man who ran the Budapest embassy during the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 can be declared an innocent. But while Andropov was guilty of many things—most notably his brutally efficient campaign against the dissidents while he ran the KGB—he was a throwback to a tradition of Bolshevik asceticism. He was appalled by the kind of corruption and rot that had become endemic under Brezhnev, his political rival. While he was KGB chief, Andropov conducted a wide-scale, independent investigation into Party business and the general state of the country. He discovered the incredible state of Soviet corruption and deterioration. In his few months as general secretary after Brezhnev’s death, Andropov ordered arrests of some of the most obvious Party and police mafiosi. He frightened the worst elements in the apparatus so badly that a series of high-ranking officials in Brezhnev’s old circle shot, gassed, or otherwise did away with themselves.

The remaining Brezhnevites at the top were not much grieved when Andropov became seriously ill. The Party mafia could not bear the thought of any reforms that would further endanger its comfort. As Solzhenitsyn wrote last year in his essay How To Rebuild Russia, “The corrupt ruling class—the many millions of men in the party-state nomenklatura—is not capable of voluntarily renouncing any of the privileges they have seized. They have lived shamelessly for decades at the people’s expense—and would like to continue doing so.”

Had it not been for that primal urge to power and privilege, Gorbachev might well have taken over as general secretary more than a year earlier than he did. Arkady Volsky, a former aide to Andropov and a leading figure in the Central Committee, told me how the Brezhnevites in the Politburo steered power away from Gorbachev, an Andropov protégé, to “their man,” the moribund apparatchik, Konstantin Chernenko. By December 1983, Andropov was in the hospital with kidney problems and blood poisoning. His aides would take turns visiting him in the hospital with important matters and paperwork. On a Saturday preceding a Tuesday plenum of the Central Committee, Volsky came to Andropov’s room at the Kremlin hospital in Kuntsevo to help him draft a speech. Andropov was in no shape to attend the plenum and he would have one of his men in the Politburo deliver the speech in his name.

“The last lines in the speech said that Central Committee staff members should be exemplary in their behavior, uncorrupted, responsible for the life of the country,” Volsky said. “We both liked that last phrase…. Then Andropov gave me a folder with the final draft and said, ‘The material looks good. Make sure you pay attention to the addenda I’ve written.’ Since the doctor walked me to the car, I didn’t have time to look right away at what he had written. Later, I got a chance to read it and saw that at the bottom of the last page Andropov had added in ink, in a somewhat unsteady handwriting, a new paragraph. It went like this: ‘Members of the Central Committee know that due to certain reasons, I am unable to come to the plenum. I can neither attend the meetings of the Politburo nor the secretariat. Therefore, I believe Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev should be assigned to preside over the meetings of the Politburo and the secretariat [of the Central Committee].”‘

Volsky knew well what this meant. The general secretary was recommending that Gorbachev be his inheritor. Volsky made a Xerox copy of the document and put the copy in his safe. He delivered the original to the Party leadership and assumed, naively, that it would be read out at the plenum. But at the meeting neither Chernenko, Grishin, Romanov, nor any of the other usual suspects in the Brezhnev circle made mention of Andropov’s stated wishes. Volsky thought there must have been some mistake. “I went up to Chernenko and said, ‘There was an addendum in the text.’ He said, ‘Think nothing of any addendum.’ Then I saw his aide Bogolyubov and said, ‘Klavdy Mikhailovich, there was a paragraph from Andropov’s speech….’ He led me off to the side, and said, ‘Who do you think you are, a wise guy? Do you think your life ends with this?’ I said, ‘In that case, I’ll have to phone Andropov.’ And he replied, ‘Then that will be your last phone call.”‘

Andropov was furious when he heard what had happened at the plenum, but there was little he could do. Even Lenin did not have the power to handpick his successor, and the Brezhnevites in the Politburo were just too powerful. Two months later, when Andropov died, Chernenko became general secretary, the ventriloquist’s dummy of the Party apparat. After the Politburo meeting that decided the question, Volsky heard one of the leading Brezhnevites tell another in triumph, “This is good. Kostya will be easier to control than Misha.”

As a concession to the Andropov faction and over the objections of some of his own confidantes, Chernenko made Gorbachev the nominal number-two man in the Politburo. This turned out to be a critical tactical mistake. Chernenko held office only thirteen months, and for much of the time he was sick and powerless. As Chernenko wasted away, Gorbachev was carefully consolidating power. He ran Politburo sessions and won the support of two critical figures—the foreign minister, Andrei Gromyko, and the KGB chief, Viktor Chebrikov. He also took his famous trip to Britain where he made a lasting impression on Margaret Thatcher and the world press. When Chernenko finally died in March 1985, Gorbachev was in position to head off any potential opposition from the mafia dinosaurs. With the likely help of Chebrikov’s KGB, two key conservatives could not even make it back to Moscow in time to support an anti-Gorbachev vote in the Politburo. Kunayev was stuck in Alma-Ata and Shcherbitsky, the Ukrainian Party chief, somehow could not coax his own plane to leave quickly enough from San Francisco to make it back in time to Moscow. Engine trouble, Shcherbitsky was told.

Gorbachev, for his part, took office without taint of blood or corruption, a first for a leader of the Soviet Union. But even his Mr. Clean image is a relative thing. As the Party leader of a resort region in the Caucasus, a neighbor of the notorious Krasnodar region, he must have known about the Party way of doing business, both with Moscow and within the local structure. It is unlikely that Gorbachev, either as the Party chief of the Stavropol region in southern Russia or in Moscow as a member of the Central Committee, could have avoided toadying behavior toward Brezhnev. Even the historian Roy Medvedev, a Gorbachev loyalist to the last, says, “I believe that presents for Brezhnev even arrived from Stavropol.”2

But Gorbachev fiercely denies any serious impropriety. He told an interviewer recently that he fired corrupt police officials in Stavropol, and for this sin he was threatened by a deputy minister in Moscow with a criminal investigation. Gorbachev has always been sensitive about rumors of corruption. On New Year’s Eve 1989–1990, the censors banned the television program Vzglyad (“View”) for “aesthetic reasons.” Vaksberg writes that the aesthetic reason in question was that Brezhnev’s daughter, Galina, told an interviewer that Raisa Gorbachev tried to curry favor with the Brezhnev family when Leonid Ilyich was in power and gave them a number of presents, including an expensive necklace. While Vaksberg points out that Galina was a drunk, he does not discount the report. But Vaksberg is also quick to recount how after he published a piece called “Spring Floods” in Literaturnaya Gazeta about the negligence of ministers while the harvest rotted in the fields, the paper got a dressing down from the Ideology Department of the Central Committee. Just as the editor was instructing Vaksberg to print a retraction, Gorbachev called the paper to express his compliments for its crusade against corruption.

Gorbachev could not conduct a genuine investigation into the Party’s corruption. First, the Party, of which he was the head, would sooner kill him than allow it. Second, even if he was able to carry out such an investigation, he would be faced with the obvious embarrassment: the depths of the Party’s rot. Instead, taking a page from Andropov’s style manual, he made a grand symbolic gesture. Yuri Churbanov, Brezhnev’s son-in-law and a deputy chief of the Internal Affairs ministry, was indicted and tried for accepting more than $1 million in bribes while working in Uzbekistan. At his trial, Churbanov admitted accepting a briefcase stuffed with around $200,000. “I wanted to return the money, but to whom?” he said. “It would have been awkward for me to raise the question with Rashidov.” Churbanov was sentenced to twelve years in prison at a camp near the city of Nizhny Tagil. Brezhnev’s personal secretary, Gennady Brovin, was sentenced to nine years in prison, also for corruption.

Like Andropov before him, Gorbachev believed in his ability to master the Party and reform it. Over a five-year period, he fired and replaced the most obvious mafiosi in the Politburo: Kunayev, Aliyev, Shcherbitsky. But just as he could never distance himself enough from a discredited ideology, Gorbachev’s inability to jettison the Party nomenklatura and his political debts to the KGB spoiled his reputation over time in the eyes of a people that had grown more and more aware of the corruption and deceit in their midst. Even now, Russians are reluctant to believe in Gorbachev’s honesty. The latest rumor, printed May 8 on the front page of Izvestia, is that Gorbachev has purchased a two-story house on the Gulf coast of Florida for $108,350.

The new wave of politicians often saw Gorbachev’s equivocations about the Party as an opportunity. Telman Gdlyan and Nikolai Ivanov, two investigators who helped convict Churbanov, became two of the most popular legislators in the parliament purely on the strength of their public attacks on Party corruption. In their investigations in the late Seventies and early Eighties, Gdlyan and Ivanov were known for mistreating witnesses, manufacturing evidence, and other illegalities. They dismissed such charges with a smirk. Gdlyan told me one day that Yegor Ligachev, the number-two man in the Politburo, had “definitely” accepted at least 60,000 rubles in bribes from an Uzbek official. When I asked for proof, Gdlyan laughed, as if such things hardly mattered.

Yeltsin was the master of the populist attack, using the issue of Party perks as a way to discredit everyone at the top, Gorbachev included. In his memoir, which was immensely popular in Russia, Yeltsin writes about the “marble-lined” houses of the Politburo members, their “porcelain, crystal, carpets, and chandeliers.” For an angry audience living in cramped communal apartments, he described his own house when he was in the Party leadership, with its private movie theater, its “kitchen big enough to feed an army,” and its many bathrooms: so many that “I lost count.” And “why has Gorbachev been unable to change this? I believe the fault lies in his basic cast of character. He likes to live well, in comfort and luxury. In this he is helped by his wife.”3

Yeltsin exploited this issue whenever he could. Once, I was interviewing him after he’d been fired from the Politburo for daring to confront the leadership in October 1987. Yeltsin was still a member of the Central Committee with all the privileges that entailed, but he swore to me that he had voluntarily given up his dacha, his grocery shipments, and his car. “All finished!” he said with the pride of the converted. For a very short while Yeltsin, a man built like a former heavyweight contender, made sure that Muscovites saw him tooling around the city in a dinky sedan. But those days were short-lived, and, now, as Russian president, he lives no worse than Gorbachev did. In fact, while Gorbachev in his time traveled about Moscow in a three-limousine procession, Yeltsin requires four. His new double-breasted suits and silk foulard ties are also, one supposes, not available for rubles.

The Communist Party, for its part, well understood not only the meaning of Yeltsin’s attacks but also the much wider issue of what a market economy and a multiparty system would mean to its future. From the first appearance of cooperative businesses in 1987, the Party did everything it could to destroy the new movement it ostensibly endorsed. One leading conservative, Ivan Polozkov, the head of the Russian Communist Party, made his name fighting the rise of cooperative businesses in the Krasnodar region. He closed down more than three hundred co-ops in the region, calling them “a social evil, a malignant tumor.” The KGB, under Vladimir Kryuchkov, waged a campaign against private business, all under the pretense of rooting out corruption. The conservatives also knew they could play games with the psychology of a people grown accustomed to “equality in poverty.” They knew they could arouse bitter jealousy in millions of collective farmers and workers by advertising instances of abuse under the new “mixed” economy. They portrayed the new wave of businessmen as hustlers (invariably Jewish hustlers) who made millions by buying products at low state-subsidized prices and then resold the same products at three or four times the price.

Undeniably, the first private businessmen in Russia are no angels—no more than the first Rockefellers or Carnegies were. But, to the Party and the KGB, what these entrepreneurs and hustlers represented was not so much evil or capitalism as competition. This was intolerable. Lev Timofeyev, a journalist and political activist who spent 1985 to 1987 in a labor camp for writing a book describing corruption in the countryside, wryly demanded that the Party men “transform themselves into men of property, landowners or shareholders.”

“Let them make profits and reinvest them, let them outrun competition and become rich. Let them be useful at last. They have a right to do that. The only requirement is that they do not prevent others from doing the same,” he wrote.

Unfortunately the party officials will hardly become successful owners of land or industries. They lack the qualities needed for becoming honest entrepreneurs and this is why they are so terrified of those who have them. They will stop at nothing trying to prolong the days of their rotten power and they are still strong enough to do it.4

Timofeyev, of course, was absolutely right. The men who organized the resistance to the market and, eventually, the August coup represented every institution with an interest in sustaining the Communist Party as an all-embracing dictator of economic activity. By 1991, ideology was hardly the point. One only need look at a list of the lesser-known coup conspirators to get a sense of the interests involved: Oleg Baklanov, the head of the military-industrial complex; Vassily Starodubtsyev, the head of the Peasants’ Union, a group of collective farm chairman vehemently opposed to private property; Alexander Tizyakov, the president of state enterprises, a group that threatened Gorbachev on December 6–7, 1990, demanding he keep the state industries in their hands; Valentin Pavlov, the former prime minister, who managed to convince Gorbachev that foreign “interests” were robbing the state blind with a “financial coup d’état” by depositing huge amounts of rubles in foreign banks.

Vaksberg’s narrative ends before the regime collapsed, but I doubt he has been much surprised by Year One of the post-Communist era.

With the Communist Party in ruins, there are still remnants of its Party structures in place and signs of new illegal clans. As in Eastern Europe, Communist Party economic apparatchiks often remain in power because so few outsiders are competent enough to run factories or administer huge bureaucracies. Especially in the Russian provinces, the former Communist Party executives, collective farm chairmen, factory bosses, and security chiefs are still in firm control. The Party men hold on to their properties with a death grip. Farmers who try to take advantage of new privatization laws often find themselves stalled or refused access to land and equipment. The Communist Party men who run the huge and outdated factories in the Urals and the Siberian rust belt have no intention of leaving their jobs to a new breed of innovators and they may have to be carried, feet first, from their offices.

At the same time, a sense of lawlessness prevails in many cities, with a new set of mobsters independent of the old Communist Party structures. They, too, are called mafia but they resemble more the unscrupulous figures of primitive capitalism, the first robber barons and their attendant thugs. An article in the business weekly Commersant mapped out in detail last year how the various clans and groupings—the Chichens, the Ramenki Brigade, the Assyrians, the Sylvester Brigade, the Gypsies, the Jews, etc.—had carved up Moscow.

With the West’s help, the direction of the economic and political evolution in the former Soviet states can only be upward. Sooner or later, the dead hand of the Party will fall away. But the progress will not always move quickly enough to escape disasters and regression. The former Party chieftains were often clever men and the smartest among them are learning to repackage themselves as champions of the market. Just look at what is happening in Azerbaijan. One of the leading politicians is the “Silver Fox” himself, Gaidar Aliyev. “I was always for democracy,” he says now. “You just never noticed.”

This Issue

July 16, 1992

-

1

Cf. The Corrupt Society, by Konstantin Simis (Simon and Schuster, 1982); Nomenklatura, by Michael Voslensky (Doubleday, 1984); The New Class, by Milovan Djilas (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982).

↩ -

2

Time of Change: An Insider’s View of Russia’s Transformation, by Roy Medvedev and Giuletto Chiesa (Pantheon, 1989), p. 55.

↩ -

3

Against the Grain, by Boris Yeltsin (Summit, 1990).

↩ -

4

Lev Timofeyev in The Anti-Communist Manifesto (Free Enterprise Press, 1990), pp. 60–61.

↩