The fecklessness of George Bush is best seen in the way he has dithered back and forth between two Republican parties for all of his political life. While yearning intermittently toward the evanescing party of his father—the Wall Street internationalist party of paternalistic “Wise Men”—he rose with the surging Goldwater party, to which his fortunes have been hostage.

Bush’s choice of Texas as a starting place is called, in his own version of his life, a declaration of independence from his father. (Actually, he was working for his father, who through a protégé, Neil Mallon, ran Dresser Industries.) But the Texas move created dependence on a state party, inchoate when he joined it, that formed the vanguard of the Goldwater movement. Goldwater made one of his early impressions on Republicans by the reaction to his Texas appearances on behalf of John Tower during Tower’s Senate campaign in 1961. It was the Texas state committee of Peter O’Donnell, a leader of the Draft Goldwater movement, that Bush managed for the Houston area, after having organized its scattered fragments in West Texas.

As Chandler Davidson has argued, the Texas Republicans had no past component of moderate views.1 It was a one-wing (right-wing) party, of no national importance until the Goldwater movement gave it an opportunity to grow, because it suffered no internal conflict with less extreme Republican views.

The story is complicated by a paradox that Bush has lived without ever understanding it. The leading state party of the Goldwater movement was given artificial assistance by liberal Democrats in its crucial moment of takeoff. It became the accidental beneficiary of the bitter fight the Texan Democrats waged against the Yarborough liberals of the 1960s, a fight that led to such anomalies as John Kenneth Galbraith’s endorsement of George Bush for the Senate in 1970 as preferable to the conservative Democrat Lloyd Bentsen—this at a time when Bush had opposed the civil rights bills of 1964 and 1966 and was actively supporting the war in Vietnam.

The Republican Party in Texas “arrived” with John Tower’s election to the Senate in 1961. He was the first Republican to win statewide office since Reconstruction, and only a concatenation of flukes had raised him up. The first oddity occurred in 1957, when the conservative Democratic Party found itself, despite desperate last-minute efforts, putting a liberal, Ralph Yarborough, into the Senate. This happened because Texas’s one-party system had no runoff at the time—the leader in the Democratic primary had always been the winner of the general election. But in the special election of 1957 (held to fill the seat vacated by Price Daniel), a Republican, Thad Hutcheson, divided the conservative vote with Yarborough’s Democratic rival, Martin Dies, and let Yarborough slip through.

Liberal backers of Yarborough like Ronnie Dugger saw how useful a Republican candidate could be in siphoning conservative votes out of the Democratic Party, giving the liberals a better chance at office. They felt they could safely “spill” those Democratic votes without creating a major Republican opposition. They were looking only at the internal dynamics of the Democratic Party, since it had been the whole ball game up to that point. Tower became the first beneficiary of this strategy. Bush would have been the second one, in 1964, but for Kennedy’s assassination. And he would have been boosted by it into the Senate, in 1970, but for Richard Nixon’s clumsy meddling.

John Tower, the son of a preacher who moved from church to church in conservative East Texas, had first attracted public notice as a country-and-western disc jockey (Tex Tower). But after a stay at the London School of Economics, he returned to Texas, in pinched-waisted Savile Row suits, dandified. His booming voice compensated—at least on radio and television—for his puppet size. In 1960, this pointy-toed little Jack went forth as a giant slayer against the towering Lyndon Johnson. Normally, this was a sacrificial Republican task. Texans would never forfeit the power that went with Johnson’s majority leadership in the Senate. But Johnson had angered many Texans in 1960, on three grounds. First, after attacking the Kennedys in his own primary race for the presidency, he had “sold out” to them by joining their ticket. Second, he was campaigning on a national platform with several items anathema to many Texans (e.g., repeal of right-to-work laws). Third, he had extracted from the legislature a hasty revision of the law that let him, simultaneously, run for vice-president and for the Senate: the majority leadership was too dear to give up on the chance Kennedy might not win.

Capitalizing on these discontents, Tower got an improbable 43 percent of the vote against Johnson, and then took his campaign in to the special election to fill Johnson’s seat after he resigned to become vice-president. This is where the liberal Democrats came to his assistance. Tower was running against the Democratic oil millionaire William Blakely, called “Dollar Bill” by his liberal Democratic enemies. Yarborough said he would “go fishing” on election day, and conservatives—tempted to jump ship and actually vote Republican—were prodded from behind by liberals muttering “good riddance” to them.

Advertisement

Tower squeaked through with that help. The state now had two enormities in its Senate representation—a liberal Democrat and a Republican—and some of the same people had promoted both of them. Young Turks had ganged up on conservative Democrats from two directions, the Texas Observer cooperating with Young Americans for Freedom. This was the burgeoning party for which Bush went to work in the Tower era. His credentials were good. He had been the principal Republican organizer in Odessa and Midland, Texas, during the Fifties—an area so conservative that it had gone for Strom Thurmond’s “Dixiecrats” against Truman in 1948, and it even voted for Lyndon Johnson’s Republican opponent for the Senate in that year. Odessa would elect some John Birch Society officials in the 1960s, though Midland Democrats mobilized to prevent any spread of the society beyond one school-board election. Bush had organized hard-core opponents of communism and attacked “encroachments” by the federal government.

In the more urban and urbane Houston he was even more successful. Harris County Republicans voted him their county chairman in 1963. Later that year he announced that he would challenge Yarborough, whose first full term was ending in a storm of recrimination over his vote for the Civil Rights Bill. The effort Yarborough forces had mounted to make conservatives leave the Democrats seemed about to backfire on them. The same moves that let Yarborough win the nomination in 1957 were encouraged by people working to repudiate Yarborough.

Yarborough was the only southern senator to vote for the civil rights bill—as Goldwater was the only nonsouthern senator to vote against it. Bush’s election strategy for 1964 was linked to the Goldwater movement by the very nature of Yarborough’s difficulties. But Bush’s ties to Goldwater would have been strong in any case. Texans had been involved in the Draft Goldwater movement from the outset—including James Leonard, who was directing Bush’s 1964 campaign.

In July of 1963, Craig Peper, the finance chairman of the Harris County Republicans, resigned in protest at Chairman Bush’s open favoring of Goldwater for the presidency. The party’s fund-raising operations should be officially neutral until the nominee is chosen, Peper was arguing. But Bush praised the Draft Goldwater people and announced that he was “100 percent” for Goldwater himself.2 Two months later, Bush resigned his county chairmanship to announce for the Senate (aiming first at that high post, as his father had). That was September 11. He had just over two months of euphoric planning to replace Yarborough and make up, with Tower, an all-Republican Texas presence in the Senate.

Then Kennedy was shot, and all bets were off. Texans were even more disoriented by the blow than other Americans. Their man succeeded to the presidency. The assassination had happened on their soil. Their law officials were being blamed for mishandling the aftermath of the crime. Kennedy had been killed in a town associated with extremists like H.L. Hunt and General Edwin Walker. The President had been killed shortly after Adlai Stevenson was assailed by hostile demonstrators in Dallas. The whole state was held complicitous in the crime—if not actually conspiring in it, at least enabling it through a “climate of hate.” Parties and candidates were asked to repudiate “extremism.” Johnson, the new president, took steps to unite the battle-scarred Democratic Party. He prevented conservative Joe Kilgore from running against Yarborough.3 He wanted peace and unity in the nation, and especially in his home state. He would be glad to have Yarborough’s vote when his civil rights act passed.

Bush, if he meant to continue his campaign in this altered world, had some basic decisions to make. As a county chairman building a minority party by encouraging defections from Democrats of all sorts, he had refused to exclude anyone. But now that the call to repudiate extremism had become more urgent, he would have to heed it, ignore it, or denounce it. Not only was Yarborough calling him a supporter of extremists; the resigned finance chairman now repeated his charges that Bush was doing the bidding of the Birchers.

Before the assassination, Bush had called attacks on the John Birch Society a form of “reverse McCarthyism.” He told the Houston AFL-CIO convention, a week before announcing his own candidacy: “I am sensitive to this label business. I think labor will be doing the same harm McCarthyism did if it continues this way.”4 He stuck by that position, though not in as outspoken a way, throughout his 1964 campaign against Yarborough. Richard Nixon had repudiated the Birch Society in his 1962 contest for governor of California, and thought this contributed to his loss that year.5 Bush tried to label Yarborough the extremist, especially on his civil rights vote. He was the “dedicated left-wing radical.”6 His vote was an example of the wrong answer to race relations, the “worn-out, one-track answer, that tired Hubert Humphrey answer, that awful Ralph Yarborough answer—the federal government must do it.”7

Advertisement

In the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination, with all the Democratic factions uniting behind the Texas President, it is a wonder Bush did so well. He got 43 percent of the vote—the same amount Tower rolled up against Johnson in 1960. Yarborough, whose family came to Texas in the 1840s, called Bush a carpetbagger with a “rich daddy” in the Senate. “I am not a good singer, but I sang on the radio Bush’s song about ‘We’re little lost sheep who have lost our way, baa, baa, baa.’ “8 James Leonard, who ran Bush’s 1964 campaign, says his eastern manner did not hurt in the metropolitan areas, especially Houston: “Bush was the Republican Kennedy, young, dashing, articulate, rich.” 9 But rural areas were a different matter. “I tried to make a Texan of him,” says Leonard,

but he would use words like profligate spender to describe Yarborough. That is where Bush differed from Tower. Tower, for all his anglophile ways, his little pinchy suits, could talk to East Texans in their own language. I sent Bush, during August, which is normally the dog days of a campaign, to tour East Texas with a country and western band. But when I caught up with him in Marshall, sure enough he was still using the word profligate. He said it was the succinct, right term.10

Bush ran better against Yarborough than did Goldwater (with only 37 percent) against Johnson. Bush got 1,134,337 votes, Goldwater only 958,566. He seems to have thought he would have done even better if he had distanced himself from the fringe crazies. He was giving himself too much credit: the anger at Yarborough’s liberal civil rights stand is what helped him—the President was not held responsible to the state as its own senator was. But Bush was feeling a natural frustration. Even he was not immune from attacks by the crazies. James Leonard says the only people who made him uncomfortable while campaigning in 1964 were the right-wingers who brought up his membership in the Council on Foreign Relations.11 His eastern origin was held against him despite all his service to the Goldwaterites. A pattern had been established, the right distrusting Bush even as he courts and submits to it.

Once the campaign was over, Bush did repudiate extremists, in a speech delivered before several audiences and published as a National Review article.12 He told audiences that the party must purge its irresponsible elements.

The Democrats didn’t hurt me with the label of carpetbagger, but I was hurt when they called me a John Bircher. And I didn’t say anything because I was afraid of losing votes. I am now ashamed for not speaking out about this type of pandemonium [?] campaign.13

Bush also told his Episcopal pastor, John Stevens, that he had gone too far in attacking the civil rights bill, using an “us against them” rhetoric being perfected in 1964 by George Wallace. Bush had said: “The new civil rights act was passed to protect 14 percent of the people. I’m also worried about the other 86 percent.”14 Stevens says Bush told him: “You know, John, I took some of the far right positions to get elected. I hope I never do it again. I regret it.”15

It is not surprising that Bush should feel the party had taken a wrong turn in 1964. Goldwater’s crushing defeat led to a consensus that the Republicans were dead as a national power for the foreseeable future. Few people realized that this was the Republican Party’s founding defeat. A “Pyrrhic victory” is supposed to be so costly that it amounts to losing. But the Goldwater campaign proves there can be a “Pyrrhic defeat,” one that accomplishes more than most victories. Four years later, Richard Nixon would lead the “dead” party into the White House, profiting from insights like those of Kevin Phillips, who saw the silver lining to Goldwater’s disaster: even when running against a southerner, Goldwater had won five southern states. The formerly Democratic “Solid South” was falling apart, under pressure of the civil rights movement.

Phillips knew that a bloc consisting of the Confederate South contained, in 1968, almost 40 percent of the electoral college votes needed to win (it now holds over half). Building on that base, Nixon would win in 1968 and 1972, Reagan in 1980 and 1984, and Bush himself in 1988. Bush had, without quite realizing it, been in at the creation of the new Republican dominance, the product of the 1964 Goldwater campaign. His fate was tied to it now, despite his intermittent fits of resistance.

Bush’s four years in the House (1966–1970) were more a detour from his destined path than an advance down it. He ran from a newly created congressional district in West Houston, a “silk stocking” district of the sort that Republican John Lindsay had held in New York in the Fifties. In Texas the “limousine liberals” in a town like Houston can be Republicans; they feel less threatened by blacks than do rural or lower-class whites. Running against a “law and order’ candidate, Frank Briscoe, Bush won more black votes than did the Democrat, even though he opposed the 1966 Civil Rights Act (open housing) just as he had the 1964 bill. Once he reached Washington, however, he gravitated toward the few “moderate” Republicans of his father’s sort. The Goldwater debacle made the leadership (Gerald Ford and Melvin Laird) have nostalgia for Eisenhower’s effort to create a Modern Republicanism occupying the middle of the road. Ford and Laird put Bush on the pivotal Ways and Means Committee, which not only approves all taxes and tariffs but is in charge of some 40 percent of the federal budget. He was the first freshman (of either party) to win a place there since 1904.16

Bush is a “moderate”—a swear word to the right—by temperament; he also believes that an openness to negotiation is effective in the long run—that enemies may “come around.” His notes to adversaries are famous. Bush supported Lyndon Johnson, in his difficult last years, on Vietnam; and he was the only Republican to go to the airport and see Johnson off when he left Washington. That would pay off, two years later, when Johnson made a pro forma endorsement of the Democrat (Lloyd Bentsen) in the 1970 Senate race, but mainly stayed home on his ranch (where he had recently entertained Bush). But the party Bush began in was not fond of compromisers.

Bush’s first-term record (1966–1968) was basically conservative—on busing, on school prayer, on Vietnam, on law and order—as the nation came unglued in riots and demonstrations. Bush had debated Ronnie Dugger in 1965, arguing that Thoreau’s civil disobedience did not extend to the Berkeley “filthy speech movement, with its offense to the moral fiber of this country.”17 He went to the civil rights encampment on the Mall (Resurrection City) to ask Ralph Abernathy, Dr. King’s successor, to disband his settlement there.18 He would later introduce legislation to make it possible for people to keep the post office from delivering obscene materials.19

Yet the turmoil of the Sixties made Bush try to pair law enforcement with recognition of some of the rights being agitated for. Despite his opposition to the 1966 civil rights bill, he did back specific legislation to allow minority home purchases—using the patriotic argument that black veterans were being blocked from enjoying the country they were fighting for. (This was the same argument that had led, shortly before, to a lowering of the voting age: the young should be able to help choose the government they are old enough to die for.)

This was Bush’s first admission that the federal government might have some role in the enforcement of civil rights—and even this one concession was too much for some of his constituents. A flood of angry letters broke upon his office, some of them containing death threats. Bush, typically, deplored the fact that his staff had to be exposed to the letters’ obscenities: “That anyone would resort to this kind of talk makes me ashamed I’m an American.” Bush appeared at a meeting of the Memorial-West Republican Women’s Club in Houston to defend his vote. He entered to boos and left to a standing ovation, arguing that a man who can buy a home is given incentives to join the system: “I see a ray of hope, not a handout or a gift, for Negroes locked out by habit and discrimination.”20

The prosperous Seventh District stuck by him, so loyally that no opponent was put up against him that year—a startling thing in Democratic Texas. No one could remember a precedent for it.21 Bush now had the surest of seats. This gave him the confidence to show greater independence in his second term. By 1969, his conservative voting record (as measured by the Americans for Constitutional Action), once in the high eighties, had sunk to sixty-nine. He even joined with some “young Turk” Republicans in trying to address the grievances of students in the 1960s (two of the Republicans on this project—Pete McCloskey and Don Riegle—became heroes to some liberals, and Riegle became a Democrat).22 Citing the tragedy of Robert Kennedy’s assassination with a handgun, Bush backed some restrictions on interstate mailorder purchases of handguns, in defiance of the misnamed National Rifle Association’s stricture on any gun control.23

His other heretical actions, for a conservative Republican from Texas, had to do with what would later be called “gender” issues. Bush was a supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment: “In fact, I was one of the House sponsors of this legislation.”24 He was also, unambiguously, pro-choice: “I, personally, feel that women should have the freedom to choose or not choose abortion, and it should always be done by competent medical personnel.”25 Bush specialized in questions of population control, energetically chairing a task force on the problem that recommended liberalizing the states’ abortion laws.26 His chairman on Ways and Means, Wilbur Mills, teased him about his crusade for family planning with the nickname “Rubbers.”27

Yet Bush’s relations with the hardline Nixon-Agnew administration, which came in as his second term began, were always warm. Nixon had favored Bush with special attention from the moment he met him as the organizer of his 1952 reception in Midland. Nixon remembered his own dealings with Prescott Bush in the 1956 and 1960 platform negotiations. (Prescott had kept to himself his aborted desire to “dump Nixon” in 1956.) Bush supported Nixon’s Vietnam policies, including the Cambodian incursion which caused an explosion on campuses. Nixon encouraged Bush to eliminate an antiwar vote in the Senate by running against Ralph Yarborough in 1970. (Yarborough had also voted to defeat both of Nixon’s first Supreme Court nominees, Harold Carswell and Clement Haynesworth.)

Bush’s father (who lived until 1972) was not a supporter of the Vietnam War. Conveniently, Bush later forgot his father’s position on the war, though the other son, Prescott, Jr., knew it well enough to cite it to an interviewer for the 1988 Frontline show “The Choice.” When I asked George Bush whether his war votes were discussed with his father, he said that they may have been, but he had no memory of it. Prescott’s war views were firmly expressed in his 1966 oral history interviews:

[Vietnam] has, I believe, extended us dangerously, both economically and militarily. I never was in favor of that buildup. President Eisenhower was strongly opposed to it. I am impressed with the position of George Kennan…. There are those who do not believe in the domino theory, that if South Vietnam falls, China will sweep to the South and overrun all Southeast Asia. China, some think—and I am inclined to believe, and certainly hope—China is not strong enough to do that. And the Russians aren’t going to go out in Southeast Asia and run all over there…. We haven’t got a single sympathetic Free World country who’s willing to help us outside of Australia, who’s in the line of fire, so to speak…. The British won’t help us. The French turn their back on us. Germany is disinterested…. So I don’t think that the course is clear that we’re the only one that’s right, that everybody’s out of step except the United States.28

Bush’s father also felt it would be a mistake for his son to give up a safe seat in the House to take on a senator with thirteen years’ seniority. But Nixon promised his support, to fend off Republican challengers in the primary. He also assured Bush there would be money coming to him from Washington. Furthermore, if Bush lost, sacrificing his House seat in the process. Nixon would appoint him to a high position. Nixon delivered on all counts, though his support in the election backfired, and his job promise turned out to be a disappointment, the job of ambassador to the UN. Nevertheless, the chance to avenge the fluke loss to Yarborough in 1964, and to win the Senate seat that had been his goal, was too tempting for Bush to forgo.

Marvin Collins, the state party’s former executive director, ran Bush’s 1970 campaign. He says: “The backing of the White House was welcome at first, since it would freeze out Republican opposition. Bush had three opponents in the 1964 primary, one of them very strong, Jack Cox. No one ran against us in 1970 but Robert Morris, the right-wing president of Dallas College, who got only 11 percent of the vote.”29 The Republican primary went like a breeze for Bush.

But the Democratic primary was a disaster. Some Democrats were as anxious to knock off Yarborough as any Republican could be. They had been prevented the last time by Lyndon Johnson’s iron enforcement, of party unity. But in 1970, former Governor John Connally was free to go after his old nemesis. (Yarborough had contested Connally’s unit-rule control of the Texas delegation to the rowdy 1968 Democratic convention, where Yarborough was supporting the peace candidacy of Eugene McCarthy.)30

Though Democrats had been lining up in 1964 to run against Yarborough, no one seemed to be on hand in 1970—another reason Bush had decided to risk his House seat. But Connally, late in the filing period, brought Houston millionaire Lloyd Bentsen out of his fourteen-year political retirement by promising full organizational and financial backing if he would take on Yarborough. If Bentsen should win, the campaign plan Marvin Collins had drawn up for Bush—to run as a moderate calling Yarborough an extreme leftist—would have to be thrown away. Bentsen was a conservative Democrat, who could well position himself to the right of a moderate Bush, cutting off any flow of conservative Democrats to Bush as the alternative to Yarborough.

The perception of Bentsen as a conservative—one he would soften some-what over his decades in Washington—was heightened sharply by the primary race he ran against Yarborough. Television ads filled the air showing riots and demonstrations all putatively inspired or supported by Bentsen’s “peacenik” opponent. Yarborough futilely said, “I never encouraged lawlessness—I’m a former District Attorney.” The Connally machine was put into high gear. Bush said, after the campaign, that he almost felt sorry for Yarborough. “I frankly don’t like the way he was beaten this year. I’m beginning to understand what it’s all about.”31

There is something a bit ludicrous in Bush’s laments over the power and money used against his erstwhile foe by the Democratic establishment in Texas. After all, Bush was drawing amply on the power and money of the Republican establishment in Washington. He was given over twice what any other Senate candidate received from the Republican Senate Campaign Committee (whose chairman just happened to be John Tower).32

There was an even grimmer aspect to the affair, one that was particularly galling to Bush and his aides. While Nixon was promising every form of help to Bush, he was courting and feting John Connally, the man behind the ads and the money that were pushing Bentsen forward to challenge Bush. Nixon had appointed Connally to the Ash Commission for reorganizing government, whose meetings were held in California when Nixon was at his San Clemente home. After these meetings, Nixon would talk politics with Connally, impressed by the man’s savvy and ruthlessness.33 Soon he was telling aides that his cabinet needed this Democrat’s energy and vision. Connally eventually won the appointment (as Secretary of the Treasury) that a defeated Bush was pining for.

Since Bush could not get to the right of Bentsen, and it was dangerous to get to his left, he and Collins had to abandon the ideological approach they had drafted for use against Yarborough. Where no difference of issues could be stressed, Bush played up his Washington connections, using the slogan “He Can Do More.” He ran on vague assurances that “I am a now congressman and he is a then congressman.” His team put out bumper stickers like “Bentsen Hedges.”

At this point, an unexpected source of help arose. The old liberal support for Republicans, which had elected Tower in 1961, was remobilized in 1970. Bentsen’s savaging of Yarborough had infuriated Yarborough’s longtime supporters. As Collins said, “Bentsen did in their hero”—and did it with the most vicious kind of negative ads. Much of the Yarborough campaign apparatus—including his former speechwriter, the young Jim Hightower—formed a Democratic Rebuilding Committee to urge support for Bush over Bentsen. Their letterhead ran a quote from John Kennedy: “Sometimes party loyalty asks too much.” 34 Liberal endorsements were solicited from around the nation. John Kenneth Galbraith’s promotion of Bush in an open letter to Texas voters would be remembered with amusement in later times:

I would like to urge Texas liberals to vote for George Bush—and to defeat Lloyd Bentsen.

As prospective senators they are, so far as one can tell, equally conservative and in the Senate will be equally bad. The argument that Bentsen will vote with the Democrats to organize the Senate should detain no one. It is unlikely that his vote will be decisive. And at a time when peace and civil rights are the two great issues, a decisive vote serves only to continue John Stennis as head of the Armed Services Committee and James Eastland as head of the Judiciary Committee. That is no great thing.

Meanwhile, a Bentsen victory will tighten the hold of conservatives on the Texas Democratic Party, force the rest of us to contend with them nationally, and leave the state with the worst of all choices—a choice between two conservative parties. The defeat of Bentsen, by contrast, will show Texas conservatives that their only chance of winning is to become Republicans. That is how it should be and what the two-party system is about.35

That last sentence was meant to counter Bentsen’s clever use of John Tower’s argument in 1961 that the state should have a senator from each party, to maintain a balanced delegation.36

So Marvin Collins saw prospects brightening by September. His strategy had been turned upside down, but with the same result. At first, he relied on conservative Democrats defecting in order to punish Yarborough. Now he saw liberal Democrats defecting in order to punish Yarborough’s victor. Bentsen was thus caught in a dilemma. He could, and sometimes did, attack Bush as a liberal on matters like gun control.37 Bush’s few liberal stands had not endangered him when he thought he would be facing Yarborough. Now they did. But if Bentsen pressed this kind of attack, he added to the ire of liberal Democrats, giving them further reasons to follow Galbraith’s advice.

The final stage of the Bush campaign had two goals—to say nothing that would discourage the liberals bracing themselves to vote Republican, and to keep the turnout low. The White House, at the last minute, wrecked both these efforts.

Republican strategists in the heavily Democratic state had always worked for a low turnout. This meant not even trying to organize or campaign in some rural areas, where the local courthouse gangs had permanent control. The fewer voters who showed up there, the better for Republicans. This strategy was especially important in 1970, since liquor-by-the-drink was on the ballot, an issue that always brought out some old Democrats in the “dry” counties. No other incentive should be added to that. Columnist Joseph Kraft, on a visit to Texas, saw and understood the low turnout strategy: “When less than half of the four million eligible voters go to the polls, the Republicans are in good shape…[so] Bush is doing nothing to stir the electorate.” 38 Bentsen, in turn, made the obvious charge that Bush’s men were “afraid of people voting…[which is] almost an indictment of them.” 39

But Nixon decided at this point that he would prove his devotion to the effort in Texas, and get some of the credit for a victory there. He announced that he and his administration—including, notably, Spiro Agnew at the peak of his campaign against antiwar liberals and protestors—would barnstorm Texas. Marvin Collins hit the ceiling. This was a blow to both aspects of the Bush strategy. The administration’s high-profile visits, with subsequent headlines, would boost attention to the campaign and increase turnout.

Even more disastrous, the provocative Agnew would sting liberals into an awareness that a vote for Bush was a vote for Nixon and his war. “Our liberal support dried right up,” says Collins, who tried to get Bush to cancel the Washington incursions. Bush refused. Why? “Well, you know he’s always been loyal to whoever. Besides, Haldeman and those guys in the White House were calling Bush weak, saying he had no balls, he wouldn’t stand up to people.”40 They meant he would not stand up to Bentsen, that he was muting their differences (the best way to encourage liberals). The real failure, though, was not to defy Haldeman and get the trips canceled. I asked Collins if he ever saw Bush make a defiant decision in the campaign. “I don’t remember any tough decisions he made that would alienate anybody that was important.”

Collins believes that Nixon and, to an even greater degree, Agnew lost Bush the 1970 election. Even so, “We got almost 47 percent of the vote.” Bush went back to Washington with a double claim on Nixon’s promise of a job. David Broder had written a column during the campaign reporting White House support for Bush—if he was elected senator—to replace Agnew on the 1972 ticket. Bush had failed to meet that requirement, but he had hopes for the cabinet post David Kennedy was known to be leaving at the Treasury.41 With a father who had served prominently on the Banking Committee, with his own business experience, with his four years on the Ways and Means Committee, Bush thought himself well qualified for the Treasury. But who should he find, back in Washington, blocking his path to the vice-presidency as well as to the Treasury but—John Connally. Nixon knew that there had been resentment among Texas Republicans over his attentions to the Democratic protégé of Lyndon Johnson. Even Connally’s appointment to the Ash Commission had brought an anguished letter from the Republican state chairman to his White House contact:

Connally is an implacable enemy of the Republican Party in Texas, and, therefore, attractive as he may be to the President, we should avoid using him again.42

But Nixon lost no time in appointing Connally to another job—on the Foreign Advisory Intelligence Board—which entailed a prestigious security clearance and regular CIA briefings. By December he instructed Haldeman to offer Connally the post of Secretary of the Treasury, and to dangle the prospect of the vice-presidency before him. Haldeman carefully prepared notes for the phone call he made to Connally:

—P [President] feels you’re only man in Dem party that cld be P.

—We have to have someone in Cab who is capable of being P.

—Overall has sympatico feeling for you.

—Feels urgently you are deep needed in this position [Secretary of Treasury] and another posit in future [obviously the vice-presidency].

—Needs you as advisor & counselor to change Treas. system, but really wants you as counselor-advisor-friend.

—Wants you cause thinks you’re best man in country as adviser in national and int affairs.

—P does not want to use you politically. Don’t give up Dem reg.

—I hope & pray you won’t turn him down. P. has fought lonely fite. If you come in, you will be closest confidante.43

Nixon’s passionate courtship of Connally resembled his idolization of John Mitchell and his more transient enthusiasm for Spiro Agnew. He admired swashbucklers, blunt men with an air of command. But at least Mitchell and Agnew were Republicans.

The difference in style between Connally and Bush explains Nixon’s different attitudes toward them. Connally, while flattering Nixon shamelessly, played hard-to-get and treated Haldeman as a menial, making him cool his heels the first time he tried to see him in the Treasury building. Bush seemed grateful for whatever vague assurances he was given. Nixon often mistook civility for weakness, as one sees in his taped references to loyal followers as “candy asses.” He admired people with a touch of the thug—and Connally certainly qualified, shocking even his own ruthless leader, Lyndon Johnson, with his cold-heartedness.44

At first Nixon said he would give Bush a White House office as some kind of presidential adviser. But then another job offer he had made—to Patrick Moynihan—was turned down. George Bush could step in there, as ambassador to the UN. Nixon had treated the UN position as something Republicans might not want—conservatives of their own party were critical of the whole organization. He had offered the job, unsuccessfully, to Hubert Humphrey and Sargent Shriver before getting another Democrat, Charles W. Yost, in 1968.45 Now, after offering it to Moynihan, he made his first overture to a Republican. The desirability of the post can be measured by the number of refusals that preceded Bush’s acceptance. People remembered all too well how President Kennedy had humiliated Adlai Stevenson in that job.

Nixon tried to sweeten the task by honoring his pledge to find Bush quarters in the White House. But the House loss, the Senate defeat, Connally’s advancement, and this second-level appointment made it look like Bush’s career had been derailed. The Texas phase was over, with little to show for it—two terms as a congressman, two defeats for the Senate, abject service to the Goldwater movement punctuated with prissy little moments of regret.

Taking the UN job was typical of Bush’s submission to whatever calls the Goldwater-Nixon-Reagan party would make on him in the future. Despite Kissinger’s humiliation of Bush at the UN (where he was kept in the dark about the China opening, even as he strove to save Taiwan’s seat), Bush volunteered for the liaison, job in China, where he was a flunky for Kissinger. Asked to take over the Republican National Committee during Watergate, Bush complied, and defended Nixon stoutly until that became impossible. Appointed director of the CIA and asked by Gerald Ford to restore appearances there, he submitted to neoconservative demands that an outside group of hardliners called “Team B” be brought in to monitor the agency for softness. Running against Reagan in 1980, he let Jim Baker withdraw him from the race, to squeeze him onto the ticket as a penitent critic of Reaganomics and overnight convert to the anti-abortion cause. The famed thick résumé of Bush is less a record of achievement than the back-and-forth trajectories of a man used as a shuttlecock by others more convinced of what the Republican Party was becoming and could do.

For all of his political life, Bush has been caught between a falling and a rising faction: unable to decide, finally, which he belonged to, trusted by neither. Though he has responded, when it counted, to the reins of the right wing, that side has never really wanted him. When he pandered to Reagan, the right thought he was undermining him—introducing dread “moderates” like his Houston doubles partner Jim Baker into the Reagan White House. To overcome this suspicion, Bush extended himself to new prodigies of pandering in 1988, licking the hands that cuffed him, crawling to the widow of his critic William Loeb, praising Jim Bakker’s evangelical soap opera, assuring Jerry Falwell he was “born again.”

No doubt Bush thought the days of groveling would end when at last he had the Oval Office to himself. The Gulf War seemed a realization of that dream. Mobilizing the nation, with his cluster of male advisers, he showed that the warfare state—complete with great secrecy and control of the press—had survived the end of the cold war. But the clear ideological justifications offered for the cold war were not present in Bush’s crusade against Saddam Hussein as a new Hitler (following on his long coddling of the same man). The consensus of the Wise Men’s time in Washington is gone, and Bush’s war prize has been wrested from him.

On the domestic front, by presenting himself as the guardian of the Reagan legacy (“no new taxes”), Bush tied his own hands. He cannot cope with the real Reagan inheritance, the deficit that turned us from a creditor nation to a debtor nation. His weak push against those restraints, the mild tax increase, brought clamoring rightwingers down upon him, calling for the head of Richard Darman, who had coaxed him toward the heresy. Thus Bush is left vaguely muttering incantations to the Market and letting the economy drift perilously downward. So far from escaping the humiliating dependence on the right, Bush is wooing them with the renewed fervor of desperation—is, in fact, leaning on his cipher of an underling. Dan Quayle.46

This is a sad but appropriate development for a man who has never sorted out his own identity with regard to his own party (or parties). With the end of the cold war, the Republican Party itself, which took its coherence from the anticommunism of its various components, is coming apart, and he is the last man to put it together again—he who never fit into either of its main branches. He is disintegrating even more rapidly than it does.

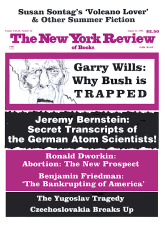

This Issue

August 13, 1992

-

1

Chandler Davidson, Race and Class in Texas Politics (Princeton University Press, 1990), pp. 200–201, 206–207.

↩ -

2

Houston Chronicle, July 3, 1963.

↩ -

3

John R. Knaggs, Two-Party Texas: The John Tower Era, 1961–1984 (Eakin Press, 1986), pp. 41–43, and an interview with Ralph Yarborough.

↩ -

4

Houston Chronicle, August 29, 1963.

↩ -

5

The national Goldwater campaign debated the John Birch Society issue and decided (as Bush did) not to repudiate members of the society but privately to exclude them from the campaign organization. (Denison Kitchel, the campaign director, had been a member, though Goldwater and his aides were unaware of this.)

↩ -

6

Houston Chronicle, September 24, 1964. The word “dedicated” was a term of art with right-wing extremists, borrowed from “dedicated Communist Party member.”

↩ -

7

Houston Chronicle, October 14, 1964. Bush also repeated the false claim brought up by Yarborough’s primary opponent, radio’s “Scotsman” Gordon McLendon, that Billy Sol Estes, the convicted Texas financier, gave unreported money to Yarborough. See also the Houston Chronicle, May 24, 1964; September 24, 1964.

↩ -

8

Author’s interview with Ralph Yarborough, February 1992.

↩ -

9

Author’s interview with James Leonard, February 1992.

↩ -

10

Author’s interview with James Leonard.

↩ -

11

Leonard interview. One right-winger, Harold Deyo, issued a pamphlet, Who’s Hiding Behind the Bush?

↩ -

12

George Bush, “The Republican Party and the Conservative Movement,” National Review, December 1, 1964.

↩ -

13

Houston Chronicle, May 16, 1965.

↩ -

14

Houston Chronicle, October 28, 1964.

↩ -

15

“Campaign: The Choice,” Frontline on PBS, October 1988.

↩ -

16

Knaggs, Two-Party Texas, p. 111.

↩ -

17

George Bush debate speech of February 1965, reprinted in the Texas Observer, December 29, 1989.

↩ -

18

Bush newsletter to constituents (Bush Reports on the Action), July 1968, in Knaggs Papers, Box 11/12, Southwestern University.

↩ -

19

Dallas News, August 1, 1969.

↩ -

20

Houston Chronicle, April 18, 1968.

↩ -

21

Houston Chronicle, February 6, 1968.

↩ -

22

Aram Bakshian, Jr., The Candidates, 1980 (Arlington House, 1980), pp. 191–192. Bakshian was staff director of the Republican task force on campus conditions. On the other hand, Bush’s Americans for Democratic Action rating, sometimes zero, never rose above 12 percent (Davidson, Race and Class, p. 202).

↩ -

23

Houston Chronicle, September 27, 1970.

↩ -

24

Bush For Senator release, citing a letter to constituents of October 12, 1970. Knaggs papers, Box 11/12.

↩ -

25

Bush campaign bulletin, August 1970, “George Bush’s Answer to the Questions People Ask,” Knaggs papers, Box 11/12.

↩ -

26

Houston Chronicle, May 8 and June 29, 1969.

↩ -

27

Jefferson Morley, “Bush and the Blacks,” The New York Review, January 16, 1992.

↩ -

28

Prescott Bush, Columbia Oral History interviews, August 1, 1966, pp. 274, 276.

↩ -

29

Author’s interview with Marvin Collins, February 1992. Robert Morris was legal counsel to extremist Edwin Walker when he ran in a Texas election.

↩ -

30

James Reston, Jr., The Lone Star: The Life of John Connally (Harper and Row, 1989), pp. 351–357.

↩ -

31

Houston Chronicle, September 27, 1970.

↩ -

32

Austin American, October 1970.

↩ -

33

Reston, The Lone Star, p. 377.

↩ -

34

“Rebuilding” file in Knaggs papers, Box 8/12. Former Yarborough campaigners on the committee included Bill Hamilton (press secretary). Al Reinert (youth coordinator), legislative aides Chuck Caldwell, Allen Mandel, John Gibson, and Reed Martin, along with campaign staffers Dave Shapiro and Tom Bones.

↩ -

35

John Kenneth Galbraith, letter of August 1970, reprinted in the Texas Observer, December 29, 1989.

↩ -

36

Midland Reporter-Telegram, September 3, 1970.

↩ -

37

Dallas Morning News, September 30, 1970.

↩ -

38

Joseph Kraft, The Washington Post, October 13, 1970. Kevin Phillips saw how Bush was depending on liberal votes: Florida Times-Union, September 14, 1970.

↩ -

39

San Antonio Express, October 1, 1970.

↩ -

40

Though Bush’s aides could not express their misgivings about the President, the local press knew that Nixon’s support could backfire. See Dallas Times-Herald, October 29, 1970, Daily Texan, October 18, 1970, and the post-election claims that Nixon lost the race for Bush (Houston Post, November 11, 1970).

↩ -

41

El Paso Herald-Post, November 23, 1970. Cf. Roger M. Olien, From Token to Triumph: The Texas Republicans Since 1920 (Southern Methodist University Press, 1982), pp. 221–224.

↩ -

42

Peter O’Donnell to Peter Flanigan, November 1, 1970, in Nixon’s papers, quoted by Reston in The Lone Star, p. 380.

↩ -

43

Haldeman notes in Nixon papers, quoted by Reston in The Lone Star, p. 381.

↩ -

44

Reston, The Lone Star, p. 418, quoting Lyndon Johnson on Connally’s lack of any compassion.

↩ -

45

William Buckley wrote of Yost’s appointment: “Charles Yost [was] a career diplomat whose continuation at the UN [where he had served under Adlai Stevenson] suggested less President Nixon’s devotion to professionalism than his indifference to the United Nations (United Nations Journal: A Delegate’s Odyssey, Putnam, 1974), p. 10.

↩ -

46

That it is not too much to say the right wing hates Bush can be confirmed in the vehement polemic written against him by the ex-chairman of John Tower’s first race for the Senate, Richard Viguerie, in conjunction with Steven J. Allen: Lip Service: George Bush’s Thirty-Year Battle with Conservatives (CP Books, 1992).

↩