Hillary Clinton was pointedly introduced, at this year’s meeting of the American Bar Association, as “the next First Woman.” First Lady has been tainted by association with such phrases as “the little lady.” But First Woman hardly solves the problem. When a woman is elected president, it will make as little sense to call her husband the First Man (what ever happened to Adam?) as to call him the First Gentleman (what ever happened to Beau Brummel?). The spouse’s role in our republic properly has no title. Kings have queens, and princes have princesses; but there is no presidentess—nor a Mrs. President. (In the latter case, the spouse of the first woman president would be—Mr. President.)

Since the president’s spouse has no constitutional office, title, or salary, some people resent a spouse’s influence on policy or politics. “We did not elect her to anything.” It has ever been so. Dolley Madison served, for a time, as her husband’s secretary; but she hid that fact from the public.1 She already knew what Rosalyn Carter would learn to her cost when she sat in on cabinet meetings, what Nancy Reagan learned when she made personnel decisions. Eleanor Roosevelt carefully wrote out the rules for being a proper wife of the president:

Always be on time. Never try to make any personal engagements. Do as little talking as humanly possible. Never be disturbed by anything. Always do what you’re told to do as quickly as possible. Remember to lean back in a parade, so that people can see your husband. Don’t get too fat to ride three on a seat. Get out of the way as quickly as you’re not needed.2

Mrs. Roosevelt did not break every one of those rules—she could always ride three on a seat. But most of them she shattered with flair. She lived in a time of crises; her husband was also breaking the rules; government was itself being redefined, and vastly expanded, in the grips of Depression and world war. Mrs. Roosevelt visited the troops, in the Pacific Theater and in Britain, like a queen mother. During this war on an imperial scale, she became a kind of democratic empress, a task for which her upper-class breeding fitted her as much as did her lower-class sympathies.

Many things did not go back to “normal” after the war—but the role of the president’s wife did. Bess Truman and Mamie Eisenhower were more seen than heard, and they were not even seen very much. Mrs. Truman stayed in Independence for long stretches when her husband was in Washington. Mrs. Eisenhower was so reclusive as to prompt rumors about secret drinking. Things began to change with the far more visible Jacqueline Kennedy, who created the expectation that every president’s wife should have her very own Project—just one, vaguely uplifting, ladylike—to keep her out from under her husband’s feet as he did his White Housework. Jackie beautified the White House; Lady Bird Johnson beautified the highways. Then followed a series of Projects so discreet that few remember them—volunteerism for Pat Nixon, handicapped children for Betty Ford (her “dependency” work came after the White House), mental health for Rosalyn Carter. Mrs. Reagan, more audibly, said no to drugs, and Mrs. Bush encourages literacy. Mrs. Quayle, standing in the wings, has declared disaster relief her project.

These Projects exemplify the social good works of the well-born that Thorstein Veblen considered a “conspicuous consumption” of socialites’ time.3 They resemble the mission societies to which ladies flock in Dickens’s novels—or in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird: “Right then and there I made a pledge in my heart. I said to myself, when I go home I’m going to give a course on the Mrunas and bring J. Grimes Everett’s message to Maycomb.”4 This kind of activity not only conforms to one of the oldest stereotypes of female concerns but sends a message by its very singleness: The isolable problem can be tended, in a stable society, without calling into question the whole set of social forces that contribute to the problem. Out of the entire syndrome of inner-city dysfunction, drugs and literacy are treated as self-contained matters, addressable as such. That is why so little impact has been made on either problem. The point of these Projects is not to engage larger political remedies, involving many agencies and issues. The Project was designed to let a First Lady avoid controversy.

It is not surprising that the president’s wife should exemplify the most conservative notions of a woman’s place. The president himself has an ambiguous station in our history. He, too, posed title problems to the electorate. What to call our non-king puzzled the Republic’s first generation. “Mr. President” was finally chosen after more honorific terms had been suggested and abandoned. As head of state, the president symbolizes values like continuity and stability, just as a hereditary monarch does. That is why the type has been so fixed—a white, male, married Protestant, middle to upper class, with children and dogs. He comes straight out of Central Casting. The exceptions only underline the rule. One bachelor (Buchanan). One Catholic—and not till 1960. No divorced man till 1980. No woman, Jew, or African American.

Advertisement

Other societies, even more sexist than ours, have had women leaders of government—Golda Meir, Indira Gandhi, Margaret Thatcher. But those women came up through parliamentary ranks—and more conventional types were installed as ceremonial heads of state. Our president is both the head of state and head of government—which explains the pressures toward familiarity and repetition. If even the elected member of the marriage is a conservative symbol, how can we expect the unelected spouse to break out of the more severe inhibitions put, in the past, on female conduct?

Yet changes are coming, and fast. No part of our society—not even African Americans, or gays, or Catholics—has had its social role more drastically redefined than the female part. Girls now grow up expecting higher education, work, careers, the power to choose their future. The pill gave new autonomy to women’s sexual activity, as abortion has to their fertility (once the defining aspect of womanhood). The pattern of the traditional president’s wife could not be more distant from this generation’s experience and aspirations—a fact confirmed by the resistance to Mrs. Bush’s appearance at the 1990 Wellesley College commencement. She seemed, to some, a visitor from another era.

In the future, it will be hard to find a spouse of the Barbara Bush type linked to any rising politician. This is not simply because of Hillary Clinton. Other candidates have had lawyer-wives (Nicola Tsongas, Ruth Harkin, Hattie Babbitt, Marilyn Quayle) or spouses of some other professional commitment. If Hillary Clinton should break the barrier, it will be by inches only. And if not she, then another, soon. Whoever the new-model wife, she will break rules on the scale of another Eleanor. Future Noras are clearly going to find, in the White House, their Doll’s House.

If Hillary Clinton does it, she will be an appropriate symbol of her sisters’ concerns. When she returned to give the commencement address at her college, it was the second time she had spoken to Wellesley graduates. In 1969, her classmates had demanded that they be given, finally, some voice at their own commencement. They chose Hillary Rodham, the president of their student government, to be the first such speaker, and she consulted widely to find out what others wanted her to say. It was the earliest public indication of her concern that young people be given more responsibility for their own lives. This desire, she said, is not a mere “liberal” or radical thing:

There’s a very strange conservative strain that goes through a lot of New Left collegiate protests that I find very intriguing because it harkens [sic] back to a lot of the old virtues, to the fulfillment of original ideas. And, it’s also a very [sic] unique American experience. It’s such a great adventure. If the experiment in human living doesn’t work in this country, in this age, it’s not going to work anywhere.

The speech got coverage in the national press, so that when Peter Edelman, who was Robert Kennedy’s legislative assistant until Kennedy’s death, was asked to put together a conference of young leaders and old, he called the newly graduated Hillary Rodham to come as a young leader. At the conference, sponsored by the League of Women Voters, Hillary met several people who would continue to be important in her professional life, including Vernon Jordan and Edelman himself. Edelman had recently married Marian Wright, the veteran of the civil rights movement who was the first black woman to pass the bar in Mississippi. When Marian Edelman spoke at Yale Law School during Rodham’s first year there, the law student was so impressed that she asked to work during her summer break for Ms. Edelman’s nascent Washington Research Project (which would soon become the Children’s Defense Fund). Edelman said she could not, yet, pay Hillary anything; but Hillary got a grant for civil-rights research that supported her during her first summer in Washington. Edelman sent her to work with Walter Mondale’s subcommittee studying the plight of migrant workers ten years after the explosive documentary Harvest of Shame. Rodham did interviews with workers and their families, assessing the hardships their children suffered. It was the beginning of a long engagement with these problems. In later summer projects, she studied children’s cases in California and in segregated schools.

Advertisement

Back in New Haven, she became involved in the Yale Child Studies Center, working with Sally Province on infant distress. Rodham got permission from the law school to fashion a special (extra) year of study devoted to children’s rights under the law. She did research for a book, Beyond the Best Interests of the Child, written by her family law professor, Joseph Goldstein, and other faculty members.5 This was the first of three widely used volumes that explored the inadequacies of the legal formula that guides courts in cases of child abandonment, neglect, or abuse. Judges are supposed to consult “the best interests of the child.” The book made the point that these interests cannot be considered in isolation from the real limits of each situation. The authors proposed a new standard: “The least detrimental available alternative.”

This standard was made real to Hillary Rodham because she had also volunteered to work with the New Haven Legal Services. One case she dealt with involved a foster parent, a black woman in her fifties, who had raised a child of mixed (black-white) parentage while the competency and claims of the birth parents were contested in the courts. “The woman was caught in a classic bureaucratic bind,” Hillary Clinton recently said in an interview. The courts decided, after a long process, that the parents had relinquished all claims, but that the “best interests” of the child could not be served by the foster parent, who now wanted to adopt the child, since that parent was fifty years old, single, and not prosperous. The court took the child away from the one concerned source of stability in her life, and put her back in a foster home to await a possible adoption that might serve some ideal “best interests.” Joseph Goldstein told me that his book did not advocate court intrusion into family life. It tried to set standards for the least detrimental intrusion where that became necessary to protect the rights of the child. “The proof that we set useful guidelines is that the book has been translated into Japanese, French, Swedish, Danish, and other languages, where the cultures of child-raising are all different.”

Rodham rounded out her work on children’s rights by consulting with doctors at the New Haven Hospital to create rules for child-abuse cases. Again, the “best interests” were not always obvious. It seems clear that no child should be abused; but is removing an abused child from parental power always the least detrimental available alternative? “For some young children, abuse may be the only attention the child got; so when you remove it, there is an extraordinary guilt: ‘I must have done something really terrible because now they do not even want me.’ ” Rodham also found subtler abuse when parents sought sterilization of “very slightly retarded children,” or abortions when the girl desired the child. Her articles on child rights are being used by Pat Robertson and others to show that she wants children to get abortions without parental consent. “But most of my experience in New Haven,” she said, “was exactly the opposite—the parents wanted the abortion, to avoid shame, humiliation, or embarrassment.”

Through Marian Edelman, who served on the Carnegie Council on Children, Rodham collaborated on what became Kenneth Keniston’s influential work, All Our Children.6 “Marian, Pat Ward, and Hillary did the research for the chapter on legal protection of children,” Keniston remembers. That chapter deals with children’s rights to education—not only in conflict with parents who would keep their children out of school but with school authorities who irresponsibly suspend or expel children. It also dealt with rights to medical care—not only in conflict with parents (e.g., Christian Scientists) who might refuse a doctor’s ministrations but with parents who irresponsibly impose on children experimental or extreme treatments (sterilization, shock treatments, lobotomies). But “the first right of a child is to a parent, where that is possible,” as Keniston sums up the main theme of his work.

Hillary Rodham’s absorption in children’s rights was such that she did not interview with any law firms in her last year at law school, though her record made her prime recruiting material. Instead she went to work full time for the Child Development Fund. She left that, temporarily, for what she calls “the chance to be a part of history” on the House impeachment staff studying Nixon’s Watergate-related actions. Most of the time she was squirreled away doing legal research in Washington, but once, when she accompanied John Doar, the director of the staff, to a press conference, Sam Donaldson ran after her, saying, “How does it feel to be the Jill Wine Volner of the impeachment committee?” (Wine Volner was the woman lawyer in the special prosecutor’s office.) She went to no more press conferences. “The most tedious work was transcribing the Nixon tapes. One we called the Tape of Tapes—it was Nixon taping himself while he listened to his tapes, inventing rationales for what he said. At one point, he asked Manuel Sanchez [his valet], ‘Don’t you think I meant this when I said that?’ “

All this time Rodham was seeing Bill Clinton, who had returned to Arkansas. Keniston says, “We knew that anyone who came back from Oxford with a stronger Arkansas accent was made for politics.” Peter Edelman, who had not yet met Clinton, thought Hillary was throwing away her great talents when she went down to Arkansas to teach with Bill. At the law school in Arkansas, Rodham set up a legal aid service for indigents. When an Arkansas community tried to close a youth commune formed nearby, she defended the commune. “The judge loved that case—it was the first time he ever wrote on constitutional issues,” she says.

She tells how a woman jailer called her to say that an itinerant preacher-lady was going to be committed in another Arkansas town. “This is just wrong,” the jailer said over the phone, “this woman is not crazy—she just loves the Lord.” Since the woman’s court hearing was just hours away, Professor Rodham had to collect her student aides and drive straight to the town. The judge threatened to keep throwing the unpopular woman preacher into jail every time the legal services people got her out. Hillary talked to the woman, found she had family in California, and told her, “People need the Lord in California, too.” Then she persuaded the judge that it was a lot cheaper to pay for a plane ticket to California than to support the woman in an Arkansas mental home.

It was out of her varied experiences in clinics, hospitals, and research teams that Rodham wrote her early articles on children’s rights that have drawn so much attention. She was trying to find a theoretical framework for pioneer efforts on a child’s rights. According to Joseph Goldstein, the articles are not as nuanced as his own work would become later on, but they reflected what was the best opinion then. In arguing for an assumption (not a ruling) of competency on the part of children, unless that can be disproved, Rodham was trying to find a rule that would let, say, a thirteen-year-old get education or medical care if a parent denied it, or have a voice in choosing a foster parent.

One of the philanthropies that helped launch Marian Edelman’s prize-winning work for children was the New World Foundation, set up by an heiress to the McCormick Reaper fortune for the promotion of peace, civil rights, education, and spiritual values. Vernon Jordan and Peter Edelman came to serve on the foundation’s board and so, in time, did their friend Hillary Clinton, who was elected to the chair in 1987. Colin Greer, the president of the foundation, remembers that Clinton opened up the board and the award process to greater participation of women and minorities. David Ramage, now president of the McCormick Theological Seminary, was the president of the foundation when Clinton arranged a conference on women’s issues to help the board assess grant proposals. He told me, “The group was extremely diverse in every way—class, ethnicity, background—and it argued on most matters. But I was astounded when the problem of physical safety came up—all the women were united on the tremendous importance of that. I had never realized how much women live in fear. I went home and constructed a chart I called The Security Circle, to guide us in working for reforms.” That was in 1985, long before the scale of abuse and harassment was appreciated by the public.

Some of the hundreds of grants made by the foundation have been criticized—although most of those singled out were given in the year Clinton, in the chair, was not voting on particular grants. A grant to the Christic Institute has been attacked because the Washington office of that organization has made unsubstantiated charges against the government; but the grant went to the Christic Institute South, which has long been involved in civil rights work familiar to the Edelmans; and it was given to promote voting rights and those advocating them.7 A grant to the National Lawyers Guild, a favorite target of Joseph McCarthy in red-baiting days, supported education on the issue of apartheid.8 (New World was one of the first foundations to divest its portfolio of South African investments.)

Colin Greer says that Clinton was always good at questioning the practicality of grant proposals. This sense of practical reform, developed partly from her work with Marian Edelman on the plight of actual children, was evident in the work she did for her husband’s educational reforms in Arkansas. She went all over the state conducting citizens’ forums, talking to school boards and teachers, immersing herself in the details of teacher testing, curriculum standardization, and student competence tests. She overcame the opposition of the teachers’ union and helped pass the program by testifying before the legislature. It was a striking achievement for a woman from the North working in a conservative southern state. Even John Robert Starr, the former editor of the Arkansas Democrat, a relentless opponent of Bill Clinton, told me: “If he does go to the White House, Hillary will be the best First Lady since Eleanor Roosevelt—or maybe the best ever.”

But the White House is not a governor’s mansion. Candidates who have weathered many state campaigns find that standards are not so much higher as different when the presidency is at stake. The conservative “role model” aspect of the office narrows choices to the safe and the predictable. An abrupt departure from the practice of former tenants causes unease. And that is even more true for the President’s wife. The possibility that a woman may give advice triggers very old fears of disruption in the sexual “chain of command.” Eve had been the devil’s instrument in Eden; and literature is full of overweening women seeking power. The right-wing journal The Spectator presents Ms. Clinton as Lady Macbeth. Richard Nixon said of her, “If the wife comes through as being too strong and too intelligent, it makes the husband look like a wimp.” That had been the case even for an obviously strong president like Franklin Roosevelt. His cousin Alice Roosevelt Longworth was quoted as saying, “Franklin is one part mush, and three parts Eleanor,” and the journalist. Doris Fleeson called Eleanor “a Trojan mare.”9 Franklin sometimes denied Eleanor’s influence on specific matters: it was all right for him to take advice from unelected male aides like Louis Howe or Steven Early, but there was something sinister about a woman’s exerting influence or offering advice. Pat Robertson attributes such female aggression to witchcraft.10 Reagan could take advice from Michael Deaver; but when the same advice came from Nancy Reagan, it was resented as baneful, as almost unconstitutional.

The White House is one of the few places left in modern life where a wife’s subordination to her husband and his career is considered not only a duty but the highest duty. She is not to have an independent sphere of interests and friends. One thing that frightened people about Eleanor Roosevelt was that she had formed a network of civil rights and peace and labor contacts quite different from her husband’s. In retrospect, we see that as a beneficial way of complementing FDR’s differently focused life; but at the time it seemed to many an encroachment, almost a usurpation.

Most presidents’ wives come into office with their worlds defined entirely by their husbands. They have to adopt a Project because they had none prior to their arrival. (When Margot Perot was asked, during her husband’s shadow candidacy, what her Project would be, she asked the reporter to suggest one to her.) Hillary Clinton would arrive not only with ongoing concerns but with an influential network of allies in the legal, philanthropic, and civil rights fields.

Much has been made of the FOBs (Friends of Bill), that large web of contacts Clinton formed as he reached out from Arkansas by way of Georgetown, Oxford, Yale, and the Democratic Leadership Conference. But Hillary went down to Arkansas bringing with her an equally important circle of loyal friends (FOHs). Through Peter Edelman, Burke Marshall (her law professor), and John Doar (her director on the impeachment staff), all of them former Robert Kennedy aides, she has many Democratic Party ties. Through Marian Edelman (who, as a young lawyer, joined Doar in his efforts against violence in Mississippi during the Sixties) she met many people deeply involved with the problems of poverty and racism. She has feminist associations, having been, for example, the founding chair of the ABA’s Women’s Commission.

In Arkansas, the FOBs and the FOHs meshed usefully; but a vision of two power centers in the White House remains deeply disturbing to conservative Americans. Even in the campaign there are rumors of conflict between “Bill’s people” and “Hillary’s people.” This would surely escalate fears in the White House. But the constitutional situation makes such fears chimerical. There is no First Lady, only a wife (or, later, a husband). A spouse’s ability to help is not a legal power but a matter of suasion; no husband has been brow-beaten in that office to do what he did not want to do. Franklin Roosevelt was coaxed into things he was at first disinclined toward (e.g., giving attention to the NAACP). Few people doubt, any more, that Roosevelt was a better president because of his independent wife. He was hardly bewitched. But it has come time for the career woman, even in the White House, to be de-witched.

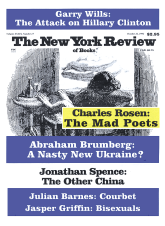

This Issue

October 22, 1992

-

1

Conover Hunt-Jones, Dolley and the “Great Little Madison” (American Institute of Architects, 1977), pp. 12–17.

↩ -

2

Joseph P. Lash, Eleanor and Franklin (Norton, 1971), p. 612.

↩ -

3

Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class (Penguin, 1967), p. 96.

↩ -

4

Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird (Lippincott, 1960), p. 244.

↩ -

5

Joseph Goldstein, Anna Freud, and Albert Solnit, Beyond the Best Interests of the Child (Free Press, 1973).

↩ -

6

Kenneth Keniston, All Our Children (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978).

↩ -

7

The New World Foundation Report for the Years 1987 and 1988, pp. 16, 35.

↩ -

8

New World Foundation Report, p. 13:

↩ -

9

Lash, Eleanor and Franklin, p. 620.

↩ -

10

Robertson attributed support for the ERA in Iowa to “a socialist, anti-family political movement that encourages women to leave their husbands, kill their children, practice witchcraft, destroy capitalism and become lesbians” (AP dispatch, August 25, 1992).

↩