1.

When the leaders of the twelve members of the European Community signed the Treaty on Monetary and Political Union in Maastricht in December 1991, the project of a United Europe, which began in 1950 under the inspiration of Jean Monnet, seemed to be making spectacular progress. A single currency, a common monetary policy, and an independent central bank were to be established in stages before the end of the century, thus bringing to its logical conclusion the design for a single European market that had been proposed in the mid-1980s. 1 The powers of the Community were also to be extended to deal with a broad range of policies concerning health, consumer protection, the environment, crime, immigration, labor relations, diplomacy, and defense. Even though Britain had refused both to accept the new social provisions of the treaty and to join the full monetary union, agreement on so vast an expansion of community activities was hailed as a great success.

Yet the signing of the Maastricht treaty marked the beginning of a serious crisis, which has led to a new wave of pessimism about Europe’s future, both on the Continent and in the US. The pessimism comes from a variety of different troubles. Every Western European economy is stagnant, the result both of the worldwide recession and the huge costs of German unification. Partly as a result, the main European governments are concentrating on their domestic difficulties and programs. Two other sources of the European malaise may be more difficult to deal with in the long run. One is often referred to as the Community’s “democratic deficit,” the much-resented distance between the bureaucracies that administer the EC and the European voters who are affected by it. Perhaps the deepest problem of all concerns the relation of the traditional nation-state to a new United Europe.

The ambitious plans that are now falling apart were the product of another recession—the one that hit Western Europe after the oil crisis of 1973 and resulted in years of “Europessimism,” fluctuations in exchange rates, and stagnation in the development of the Community. Even Britain’s entry into the EC didn’t help, since the British spent, in effect, ten years—between 1974 and 1984—renegotiating the terms on which they had been admitted. In 1978, the French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing and the West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt took the initiative to set up a European Monetary System (EMS) that would create monetary stability by narrowing the range of exchange rate fluctuations among the members’ currencies. This seemed one of the more striking European successes of the postwar period. Devaluations and reevaluations of currency were not ruled out, but they became increasingly rare. Britain, which had at first stayed out, finally joined the EMS in 1990. The EMS was to be the basis on which a full monetary union, ultimately with a common European currency—an objective toward which Jaques Delors, the president of the EC’s Commission, had been working for years—was going to be built.

Progress toward monetary union, as defined at Maastricht, required that the members’ economic and fiscal policies would converge with regard to inflation, interest rates, deficits, debts, and currency stability. The treaty set up guidelines that participants in the enterprise were to meet, and, as has been the case during the 1980s, these corresponded to the preferences and policies of the German Bundesbank. Maastricht was supposed to continue the process by which both Britain and (after the grand reversal of the Socialists’ economic policy in 1983) France pursued economic strategies, including high interest rates, that aimed at monetary stability and at reducing inflation. Even when the American recession began to reach Europe, these policies continued.

But German reunification, beginning in 1989, destabilized the EMS. Chancellor Kohl’s decision to establish a one-to-one exchange rate between the Deutsche mark and the Ostmark and to accept wage parity between the workers of the Federal Republic and the far less productive workers of the former Democratic Republic led to enormous reductions in income, employment, and production in the East, and obliged the German government to transfer huge amounts of public funds there. Kohl’s reluctance to raise taxes resulted in large borrowing and a big deficit; the rise in Germany’s inflation (which had preceded unification) worsened. The independent Bundesbank reacted by raising its interest rates by six percentage points in five years in order to combat inflation. But this obliged Germany’s partners in the EMS to raise their own interest rates in order to prevent an outflow of funds from their countries to Germany and to preserve the stability of their own currencies, the result being lower economic growth and higher unemployment.

In Britain and France, politicians, economists, and businessmen (such as Jacques Charvet, the head of Peugeot, in France) began to question the wisdom both of sacrificing growth to sustain artificial exchange rates and of following the dictates of the Bundes-bank, which had become the de facto European Central Bank, yet acted only according to its view of the German national interest. Also the international money markets, computerized and deregulated, began to sell gigantic amounts of currencies that appeared overvalued, such as the peseta, the lira, and the pound. The central banks that tried to defend their currencies by purchasing large amounts of them on the market simply did not have the reserves to succeed in doing so. The daily turnover in currency markets reached $900 billion, while the reserves of the G7 nations amounted to less than a third of this sum.

Advertisement

In early September 1992, the European governments failed to agree on an official currency realignment that would have slightly adjusted the value of currencies in relation to the market. The French objected because of possible negative effects on the difficult campaign to get the French public to vote for the Maastricht treaty, the British because they insisted, in vain, that the Germans reduce interest rates. This led to the uncontrolled devaluation of the pound, the lira, and the peseta, and to Britain and Italy’s withdrawal from the EMS after the Bank of England’s failure to support the pound even after spending half of its reserves.2

The EMS is not dead. With much help from the Bundesbank, the French were able to resist the markets’ onslaught on the franc, and thus to keep their currency within the margins of fluctuation required by EMS. As long as EMS is alive, there is a chance for monetary union, but it is clear that Britain, now embarked on a policy of reduced interest rates and monetary autonomy, will not rejoin it in the near future. Nor will Italy, Greece, and Spain, among others, meet the “convergence criteria” set up by EMU. There will be increasing pressure on the Bundesbank, particularly from the French, to lower German interest rates so that these rates can be lowered in France and elsewhere, and the way opened to more growth and reemployment.

If the Bundesbank resists French pressures, the French politicians who argue against any further sacrifice of the French economy on the altar of monetary stability will gain influence. Moreover, the entire experience has strengthened the position of those in Germany who oppose the Maastricht treaty, believing that the dilution of the power of the Bundesbank in a European Central Bank, accompanied by a disappearance of the German national currency, would be a mistake. Thus, even a European Monetary Union limited to the stronger currencies among the twelve EEC nations remains at the mercy of the recession. If the recession prolongs the agony of East Germany’s merger with West Germany, which is the cause of the Bundesbank’s reluctance to lower interest rates, and one of the causes of the unemployment crisis in France,3 the chances of organizing a European Monetary Union will be slim. But should the Bundesbank become more lax, Germany’s own ability to meet the criteria for economic convergence would be even more compromised. The great step toward a monetary union planned at Maastricht now appears to have been premature.

What the financial crisis has shown is the impossibility of bringing about monetary union without a close coordination of national economic policies—and the fact that, at present, there is a huge discrepancy between a single, deregulated market set up and monitored by the Community and the tax, labor, monetary, and other economic policies that are still in the hands of the national governments. When these governments are determined to pursue the same type of economic policy—as was the case of France and Germany in the 1980s—the EC can make progress; but when the governments are incapable of pursuing the kind of policy preferred by the Bundesbank (as with Italy) or rebel against it (as with Britain), such progress stops.

Resuming the quest for monetary union will require that the governments of Western Europe put their respective economic houses in order. But if they concentrate on politically difficult domestic issues, such as lowering unemployment, they are likely to give less attention to all the other aspects of European unification, and indeed to become all the more impatient with them.

The governments of the EC’s “big four” have all turned inward. Of these countries, Italy has always been the most strongly and sentimentally enthusiastic about European unification—but also the least capable of enforcing the rules and directives of the EC because its government has been so disorganized and inefficient. Its regional institutions are sometimes more competent, but Italy is the one country whose regions have no representation in Brussels.4 Moreover, the current apocalyptic crisis in Italian politics, which has undermined the entire postwar political leadership and the constitutional system, will only reinforce the need to concentrate on domestic matters. To shift from an increasingly corrupt system of unaccountable public enterprises and patronage to a new, reformed Italian administration will be painful and tricky. Under prodding from a public that has long been complicit and cynical but finally has become fed up, such a shift will have to be carried out by the very people who have become targets of popular wrath, the beneficiaries of the old order. A successful economic reform might allow Italy to rejoin the European Monetary System and to put itself in shape for the European Monetary Union—but this would be an immense task, in view of Italy’s debts and deficit.

Advertisement

The British concentration on domestic affairs and hostility to Europe extends beyond John Major’s government, which decided that British growth must prevail over European monetary cooperation. Along with most conservatives, Major believes that the Thatcherite victory over trade unions has to be protected from the proposed EC labor charter with its liberal provisions on such matters as union rights and powers and factory conditions, which are abhorrent to British employers.

The genteel resentment of Britain’s postwar decline—relative not only to France but even to Italy—which was so evident in the 1960s and 1970s, and which had been among the sources of Mrs. Thatcher’s appeal, has not disappeared. It has only been supplemented by an awareness of the dark sides of Thatcherism (the gap between the richer and poorer parts of England) and of its failures (in industry or education), and by the discrediting of once sacred institutions, including the monarchy. None of this has made the British keener to participate in the EC. Nostalgia for Britain’s “finest hour,” in 1940, and for the days of empire, is still there. The special concessions Major had obtained at Maastricht, as well as the monetary crisis of last September, seem only to have strengthened the British tendency to want to have the advantages of being in the European “club” and the single market, but only as long as they do not clash with American policies and the British sense of distinctiveness. Britain’s enthusiasm for extending the EC to the newly liberated countries of Eastern Europe derives largely from the old and constant British desire to turn the Community into little more than a free trade area with as few common rules and policies as possible.

The new French government has, by contrast, renewed France’s strong commitment to the EC, to the European Monetary Union, and to a common European security system. The prime minister, Edouard Balladur, by his statements and appointments has subtly constrained his “boss” Jacques Chirac, who is expected to run for president in 1995, and has been known to veer opportunistically from statements of shrill nationalism to proclamations of good Europeanism. Balladur’s mission is to manage the economy, with its three million unemployed, in such a way as not to undermine Chirac’s chances in 1995, and this concern will determine his attitude toward the EC. If the EC can be used to provide tangible benefits for France (a reduction of interest rates by the Bundesbank, for instance), it will be applauded. If it tries to impose sacrifices on French farmers, because of the preference that most EC members (including Germany, if not German farmers) have for a GATT agreement on freer agricultural trade, even at the expense of a very small part of the French peasantry, the EC will be resisted. It is most unlikely that the government will accept a compromise that would cost Chirac, a former minister of agriculture, the votes of France’s farmers, most of whom vote for the right but were against Maastricht.

As for Germany, it will hold many elections next year—local, state, and federal—and its government will have to deal above all with an electorate whose mood has been soured by the most serious recession in the postwar era, by the flood of refugees who have sought asylum (and against whom the growing far-right movements have turned their violence), and by the nasty revelations of the Stasi files in the East, which have worsened the climate of suspicion and resentment. The psychological gap between the West Germans, proud of their economic performance and of their ability to confront and repudiate the Nazi past, and the East Germans, accused of having bad working habits and a bad conscience as well, has not been closed. The many insecurities that afflict the public of a country whose internal tensions have, in the past, spelled trouble for much of Europe, are now central concerns of Germany’s tired and divided government, which has only one year and a half to go. The government’s main party, the Christian Democrats, has been slipping badly in the polls and in votes in state elections.

The overriding need felt by leaders throughout Western Europe to concentrate on domestic difficulties and to try, during a time of economic troubles, to cope with widespread public impatience with politicians, their stilted language, unfulfilled promises, and scandalous behavior, helps to explain why the Maastricht treaty may become a dead letter. So do the decline, except in England, of “established” parties (in France last month, the Socialists and the moderate right got only 57 percent of the vote) and the rise of extremism in Italy, France, and Germany. Instead of the common European policy on asylum called for by the end of 1993, new German legislation unilaterally declares that refugees who come to Germany from its eastern and southern neighbors do not deserve asylum.

As for a common European foreign policy and defense, nothing has done more to tarnish the prestige of the EC than the disastrous tragedy in Yugoslavia. The most “activist” of the EC members, Germany, prematurely pushed for recognition of Slovenia and Croatia. Germany has been the most indignant about Serbian crimes in Croatia and Bosnia, while remaining the one state that is constitutionally unable to fight outside its borders. (Hence the limited significance of the Franco-German Army Corps.) Those countries that can fight, such as Britain and France, have had no desire to go beyond humanitarian involvement. The EC’s impotence and its eagerness to dump Yugoslavia on the UN reflect, once again, its members’ overriding domestic political preoccupations.

2.

Such a conclusion may seem unfair, since diplomacy and defense, unlike agriculture or the single market, are still matters in which the EC members can act only when they are unanimous. But here we come to the third kind of crisis. The machinery of the EC has become increasingly complex and opaque. One of the reasons why the majority of the Danes and almost half of the French said no to the Maastricht treaty in 1992 was that the text was nearly incomprehensible. Drafted after the heads of state and government had left Maastricht, it was written by and for lawyers and bureaucrats and required legal experts to explain it.

The more clarification was provided, the more it became apparent that with the extension of the Community’s competence came a vast tangle of procedures—cases in which decisions can be taken by a two-thirds majority, cases requiring unanimity, cases in which a two-thirds majority can decide because of a unanimous decision to allow it to do so—creating an almost impenetrable maze. Few Europeans really understand how the EC works. It has a dense network of committees on which bureaucrats serve both as national agents and European civil servants, and an extremely cumbersome machinery. The Commission, charged with taking initiatives and applying decisions, is made up of supposedly independent leaders appointed by the members. The Council, composed of government representatives, is a legislative body, quite distinct from the Parliament in Strasbourg, whose discussions, budgetary deliberations, and “co-decisions” on some matters with the Council are barely comprehensible to the public.

Hence the widespread lament about a “democratic deficit.” The Council is the chief legislator, while the popularly elected Parliament has only very limited powers. The Commission, set up by the governments but basically not accountable to them or to the Parliament, is the main organ for taking initiatives and drafting regulations. The almost three hundred measures that were needed to create by 1993 a single market for goods, services, capital, and people were drafted by the Commission, submitted by it to the Council, which turned them into three hundred directives and regulations; these were then discussed by the Parliament, and referred to the member countries for enforcement by the national bureaucracies.

Such a setup is obviously very different from that of a federal democracy. During the negotiations over political union, not only the UK and France but the EC Commission opposed any dramatic increase in the Strasbourg Parliament’s powers. The UK and France wanted, of course, to preserve the Council’s preeminence because they can use it to assert national interests. But why was the Commission hostile to giving more power to the Strasbourg Parliament as well? The parliamentarians were said to be given to ceaseless, irresponsible talk. But how can they be expected to be anything else if they have no real powers?

Even more serious is the problem of the relations between the EC’s institutions and national institutions. National parliaments in the EC countries, where parliamentary government is the norm, feel doubly dispossessed. Everywhere in Western Europe, it is the executive—i.e., the cabinet—that initiates the main legislative acts and sets the course for the nation. Quite unlike the system in the US, parliaments have only the choice between overthrowing the cabinet (and thus often risking their own dissolution) and accepting the cabinet’s proposals. The transfer of an increasing number of state functions to Brussels has already reduced the sphere in which national parliaments can act and under the Maastricht treaty they would be reduced even further. These functions, moreover, are to be carried out not by a supranational parliament, but by the representatives of the national executives.

Quite understandably, a backlash has occurred. In amending the French constitution so as to make it compatible with Maastricht, the French Senate insisted that EC legislation be submitted to the French Parliament. But it also said that the French Parliament could do no more than pass “resolutions” approving or disapproving the EC’s decisions, which often take the form of complex package deals, negotiated in Brussels, that cannot usefully be dealt with by a simple parliamentary resolution. If similar resolutions are passed by parliaments in other countries this would lead to paralysis rather than to a closing of the democratic gap.

An attempt was made at Maastricht to appease such fears of dispossession by invoking the principle that the Community should deal only with what cannot be handled “effectively” at the national level. But of course much of politics is itself a struggle among people with conflicting views precisely about the level on which decisions should be taken. This “principle of subsidiary,” borrowed from Catholic thought, is of no help: it does nothing to make the ec more democratic, and could do much to provoke a constant tug of war between the national states and the ec.

The Byzantine complexity of the whole structure will be aggravated by the increasing heterogeneity of the ec, which will grow even further if new members join. One now hears talk of a “flexible Europe” in which all members will have to sign the same charter, but exceptions, transitory periods, and special provisions will be granted to those who otherwise wouldn’t or couldn’t join. Denmark, for instance, has obtained a special deal aimed at making a “yes” vote in the forthcoming referendum more likely. Under it, Denmark accedes to the Maastricht treaty but not to most of its provisions. The more Byzantine the structure, the less democratic it will be.

Two proposals are being made to deal with the democratic deficit. There could be a second house of the Parliament, composed of delegations from the national parliaments. This would associate these delegates more closely with what goes on in the ec. However, this arrangement would only intensify and duplicate a flaw of the present system: the Parliament is elected not so much as a truly European assembly, but as a collection of national deputies, who run, in their respective countries, on purely national slates, and campaign not on European but on national issues. A truly European assembly would presuppose not nation-wide slates of candidates but slates elected by smaller constituencies, and composed not only of natives, but of people of different nationalities.5 This would be a second way of dealing with the democratic deficit—if, and only if, the election of such an assembly was accompanied by a major expansion of its powers. Indeed, without such an increase, neither method would resolve the issue.

Most of the European governments have been reluctant to increase the Strasbourg Parliament’s powers and to change its makeup not only because they are the major beneficiaries of the “democratic deficit” but because both reforms would clearly turn the ec in a federal direction. The reforms would thus dissipate the deliberate ambiguity that has characterized the Community since the beginning and has allowed it to proceed despite the different conceptions that exist among and within its members about its goals. Is the ec destined to become a federal state, more or less on the American model, or is it to be a particularly active regional organization, governed by its members? In other words, is the purpose of the enterprise a transfer of sovereignty from the nations to the new entity, or is it to pool the sovereignties of the members, in a way that acknowledges their growing inability to reach national goals by purely national means, yet does not oblige them to transfer sovereignty to a superior power?

The reality is somewhere in between. The two “federal” bodies that are supposed to represent the common interest—the Commission and the Parliament—are weaker than the Council dominated directly by governments. On the other hand, especially with the increasing practice of making decisions in the Council by two thirds majorities (as opposed to unanimity), the transfer of final authority in some important matters (agriculture, external trade, competition policy) to the Community, and the largely completed establishment of a single market, the ec has more of a federal character than any other regional organization that has ever been organized. It is a unique experiment, but its very uniqueness has provoked a profound doubt and distrust about the relation of the Community to the national states and public. The debates on Maastricht in Denmark, France, and now Britain have brought such feelings to light. Their sources are not difficult to understand.

First, in recent years, the activities of the Brussels bureaucrats have expanded, often in somewhat absurd ways, literally regulating ways of making cheese. As a result, Europeans tend to believe that Brussels already dictates, as Jacques Delors imprudently predicted, 80 percent of what affects their daily lives. But in fact Brussels firmly controls little more than agriculture, the elimination of regulations that hamper competition and trade among Community members, and trade with countries outside the Community. The ec does not try to establish uniform standards and rules. As long as certain minimum standards set by the Community are observed (for instance for health and safety or environmental protection) each state is simply obliged to recognize as valid the standards and regulations set up by each of its partners. The public, suffering from unemployment and connecting it to high interest rates, tends to blame the ec for what are, basically, still national policies. The Maastricht treaty, for all its verbiage, was a modest treaty (even insofar as emu is concerned, in view of the conditions and stages specified in the treaty), but it was overpromoted as a major advance.

This made the discontented members of the public—who blamed layoffs and cuts in subsidies on the single market and on reforms in the ec’s bloated agricultural policy—even more suspicious of the next stages. Even if the ec’s procedures were more democratic, it would be a target of expressions of social and economic unhappiness: in every democracy, it is the government and the bureaucracy that are held responsible for events or trends they often can’t control. In fact, the powers given up by European states have not all been transferred to the ec’s institutions; many have gone to the private investors and speculators who are central to the European economy and to world finance. Indeed, the single market is a boon to industry and especially to multinational enterprises. They have exerted far greater influence on the recent development of the Community than the labor unions, which have been weakened by the recession. This in turn strengthens the objections of those who believe that the duly elected representatives of the various member countries are no match for the combined power of unelected European bureaucrats and businessmen.6

Secondly, the relation of the nation-state to the Community is not every-where the same. For many years, the French, who dominate the Brussels bureaucracy, saw in the ec a vehicle for French influence and for imposing restraints on the power of West Germany. Today, and for good reasons, the fear of Germany dominating the Community has replaced (as also in Denmark) the old fear of an unshackled Germany outside the Community. Especially after unification increased the relative weight of Germany among the Twelve, the Federal Republic’s economic and financial might has made the ec an instrument of German influence. It has done so both through Bonn’s willingness to dispense funds to (and thus obtain business from) the poorer members of the Community, and by using its influence to maintain a decentralized ec whose institutions resemble those of the Federal Republic far more than they resemble those of France.

It may seem excessive to say that, in the ec, what Germany wants, it gets, especially since the German government remains determined not to want anything that would cost it the external support it deems indispensable. Basically, however, Germany does get much of what it wants, and what it doesn’t want doesn’t get done. The European Community has been central to the rise of Germany. It has lifted Bonn step by step from its constricted and shriveled sovereignty of 1949, to its full legal sovereignty in 1990.

For Britain, which never even began to win its bet on finding new channels of influence through the Community (largely because of its own ambivalence), and for France, which has found the post-cold war world far less hospitable than the “order of Yalta” it once so vigorously denounced,7 the Community is beginning to look much less desirable. For Britain it seems more like a cage from which the country is trying to liberate itself. For France it is worth staying in the ec as long as Germany is in it, but the French have increasing doubts about who is the guard and who is the captive. Hence the appeal, during the French referendum campaign over Maastricht, of those who said they were not “against Europe,” but only against “Maastricht’s Europe.” They argued for a different kind of Europe that would extend father Eastand allow for greater French independence at the same time.

This nostalgia for independence results not only from a geopolitical fear of being diminished. It springs from a third and more ideological or mythical consideration, powerful both in France and in the UK. Both are countries in which the nation has been created by, and remains inseparable from, the state—in contrast to the national history of Germany and Italy. The British ideological tradition, revived by Mrs. Thatcher, associates the notion of parliamentary sovereignty within the United Kingdom (however empty of substance it is in reality) with that of Britain’s external sovereignty, i.e., its power to act without constraint in Europe.

France’s Rousseauistic, Jacobin, and Republican tradition, evoked by De Gaulle and, in 1992, by the Gaullist Philippe Séguin, the new speaker of the National Assembly, combines France’s claim to external sovereignty with its insistence on the domestic sovereignty of the people (another potent myth). Most of the governments of the Twelve have, pragmatically, treated external sovereignty quite differently—as a bundle of powers that could be traded off and pooled. In most ec nations the institutional setup of the Community has diluted the strength of parliamentary or popular sovereignty at home. But in France and in the UK, much of the public remain attached, in a Danish commentator’s phrase, to a view of sovereignty as “something like virginity”: it is not divisible.8

Nations like France and the UK, where the state is seen as the source of rights and duties, and as the source of the nation itself, can only interpret the distinction which the ec encourages between the nation and the state (whose powers are now shared with the ec) as a dangerous and disturbing trend. The distinction points, indeed, to a European state, but one without a European nation, since there are still no European mass media, parties, interest groups (except in business), or public. The establishment at Maastricht of a common European citizenship is only a formal first step. Without such a European nation, many feel, so to speak, denuded, for the national state is losing power, but the European would-be state, uncomfortably straddling nations with diverse traditions and interests, seems incapable of defining a common policy in matters as vital as defense and diplomacy, as the failure in Yugoslavia shows.

In France and the UK, by contrast with Germany, the state was seen and embraced as the founder and guardian of the nation. Its weakening and replacement by a weak multinational pseudo-superstate only increase fears about national identity. The same fears are already inflamed by the influx of “others,” such as immigrant workers and refugees, or by the “Americanization” of popular culture, or by the decline of traditional ways of life, whether of British miners, French peasants, or small shopkeepers throughout the continent. The Community had been celebrated as a way, the only one perhaps, to preserve “European distinctiveness,” particularly from American pressures and cultural influences, but of course the bureaucrats in Brussels could never do this. It is not surprising that in the 1992 debates on Maastricht, the treaty’s opponents blamed the ec for every threat to national identity, for yielding to American policy over gatt or to American television imports, as well as for opening borders to more immigrants (a charge that had little basis in the treaty).

Countries like France and the UK, whose identity was shaped early and whose people see the nation as a long-defined and completed entity, have far greater difficulty accepting the implications of an ever-expanding Community than, say, Germany, which like the US, although in a very different way, tends to see itself as unfinished and continuously developing. The Germans almost permanent uncertainties about German identity some-how make it easier for them to endorse a European identity which is equally uncertain and unfinished. French and British certainties about their national past and character are being shaken, and the ec is seen as one of the culprits.

This does not mean, in either case, that the policy of European integration will be abandoned: there is no turning back. But resistance to integration, fed by the ec’s institutional flaws, is likely to increase as the ec’s powers expand. So will the gap between the European governments, for whom joint action (or inaction) has become second nature (especially since it is often unchecked), and their citizens, who wonder where their governments are taking them and who benefits and who loses, from the march to an unknown destination. Western Europe today is a collection of bruised nations, whose states have traded visible and distinctive power for diffuse collective influence.9 It is not surprising that so many Europeans find it difficult to identify with a “Europe” that remains a purely economic and bureaucratic construction and shows few signs of becoming a nation.

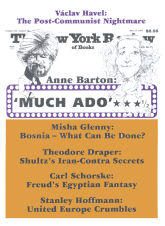

This Issue

May 27, 1993

-

1

See Robert O. Keohane and Stanley Hoffmann, editors, The New European Community (Westview Press, 1991).

↩ -

2

I have relied on the account in David Cameron’s still unpublished paper “British exit, German voice, French loyalty: defection, domination, and co-operation in the 1992-93 ERM crisis,” March 1993.

↩ -

3

There are other causes: the world recession, of course, the unstoppable decline of traditional industries in the mid-1980s, the need to be competitive abroad (a need made more acute by deregulation and the policy of tying the franc to the mark), which led to large-scale layoffs in a country where labor costs are high.

↩ -

4

See Paul Ginsborg, “Lo stato italiano: transformazione o transformismo,” La Rivista dei Libri, March 1993.

↩ -

5

Only the Italian Communists have put distinguished foreigners on their list in elections to the European Parliament.

↩ -

6

See Nicholas Hildyard, “Maastricht: the Protectionism of Free Trade,” The Ecologist, Vol. 23, No. 2 (March–April 1993).

↩ -

7

See S. Hoffmann, “French Dilemmas, and Strategies in the New Europe,” in Joseph Nye, Robert Keohane, and Stanley Hoffmann, editors, Europe After the Cold War (Harvard University Press, forthcoming next month).

↩ -

8

Ulf Hedetoft, Sovereignty, Identity and War in 90s Europe, Department of Languages and Intercultural Studies (Aalborg: Aalborg University, 1993), especially pp. 14–38.

↩ -

9

See Wolfgang Merkel, Integration and Democracy in the European Community: The Contours of a Dilemma, Working Paper 42 (Madrid: Instituto Juan March de Estudios e Investigaciones, 1993).

↩